Cover Story | The 2017 High Blood Pressure Guideline: Risk Reduction Through Better Management

The speculation is over. The new classification of blood pressure (BP) levels and changes to treatment algorithms have been announced. The usual questions have been answered on which drug for starting treatment and the targets. But, the first comprehensive guideline addressing high blood pressure since 2003 — and the successor to JNC 7 — contains much more. Among the highlights are risk assessment for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) to guide treatment, along with strategies to improve hypertension treatment and control, proper BP measurement and structured, team-based approaches to care.

The ACC and American Heart Association (AHA), together with nine partners, developed and published the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) requested the ACC and AHA lead the development of this guideline, after deciding to discontinue guideline development as of 2013.

As expected with a guideline of this caliber, the highest standards were used to develop the recommendations and to govern conflicts of interest and relationships with industry. An extensive literature review was conducted, summarized in evidence tables in the published document. In addition, the strength and quality of the evidence for the recommendations are reported. Four critical questions were defined and then answered by an external, firewalled review committee. “Another strength of the guideline is the diverse Writing Committee, including two active lay members, ensuring a breadth of expertise and opinions,” says Paul K. Whelton, MB, MD, MSc, who served as its chair.

It’s About the Risk

Hypertension is the number one cardiovascular risk factor and the world’s greatest risk factor for death and disability, according to the World Health Organization. “This guideline goes into great depth about addressing risk,” says Robert M. Carey, MD, vice chair of the Writing Committee. It’s fundamental: preventing events requires optimizing the management of high blood pressure. The 2017 guideline provides the information that every member of the cardiovascular team needs to contribute to optimizing care of high blood pressure in their patients.

It starts with accurate BP measurement and formal assessment of 10-year cardiovascular risk using the ASCVD risk estimator to determine when to start treatment with antihypertensive agents, in addition to lifestyle change, for patients with stage 1 hypertension. Correctly classifying a patient’s BP level, diagnosing high blood pressure and determining risk requires correct measurement. A checklist detailing the steps for accurate measurement of BP is provided in the guideline.

The diagnosis of hypertension should be based on an average of ≥2 carefully recorded readings obtained on ≥2 occasions. Out-of-office and self-monitoring of BP measurements are recommended to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension and for titration of BP-lowering medication, in conjunction with clinical interventions and telehealth counseling.

The guideline provides information on using out-of-office monitoring to recognize white coat hypertension and masked hypertension, each found in about 15-25 percent of the population. Whelton notes the substantial evolution in understanding these entities, including the propensity for patients with masked hypertension to have a similar risk for cardiovascular disease compared with those with sustained hypertension. Screening, follow-up and treatment recommendations are provided, along with algorithms for detecting white coat or masked hypertension in patients who are and are not taking drug therapy.

Secondary causes of hypertension are responsible for high BP in approximately 10 percent of patients with hypertension. Renovascular disease, primary aldosteronism and obstructive sleep apnea are the three most prevalent causes of secondary hypertension. The guideline provides suggestions for clinical presentations that warrant screening for secondary forms of hypertension and guidance for conduct of specific screening tests. Comorbid conditions should also be evaluated and management adjusted accordingly. This includes stable ischemic heart disease, heart failure, chronic kidney disease or renal transplant, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes or metabolic syndrome, atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease or aortic disease.

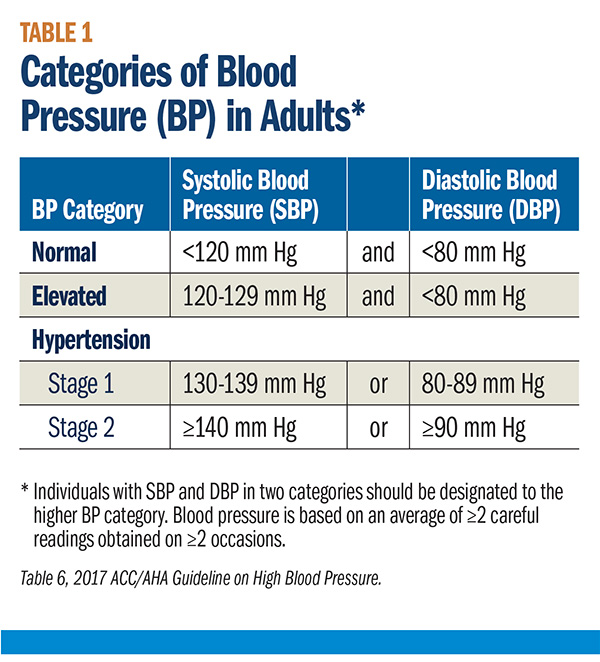

The new BP classification communicates the level of risk associated with the BP range (Table 1), based on the currently available evidence. BP should be categorized as normal, elevated, or stages 1 or 2 hypertension to prevent and treat high BP.

“The terms prehypertension and high normal are not used in this guideline, because they have the potential to be misleading,” says Whelton. Patients and physicians might misinterpret these designations to mean no action is needed. Just the opposite is true — patients with a BP in the range of 130-139 mm Hg systolic or 80-89 mm Hg diastolic are at about twice the risk of their counterparts with a normal level of BP and “we’ve clarified this by calling it stage 1 hypertension,” notes Whelton.

While many may focus on the notion that more people will now be considered to have hypertension, Whelton states “this is the right thing to do, because of the doubling in risk.” Adds Carey, “the literature has driven this, clearly showing that lower is better to reduce risk.” Key trials contributing evidence for the guideline recommendations were SPRINT, ACCORD and SPS3.

"The terms prehypertension and high normal are not used in this guideline, because they have the potential to be misleading." — Paul K. Whelton, MB, MD, MSc

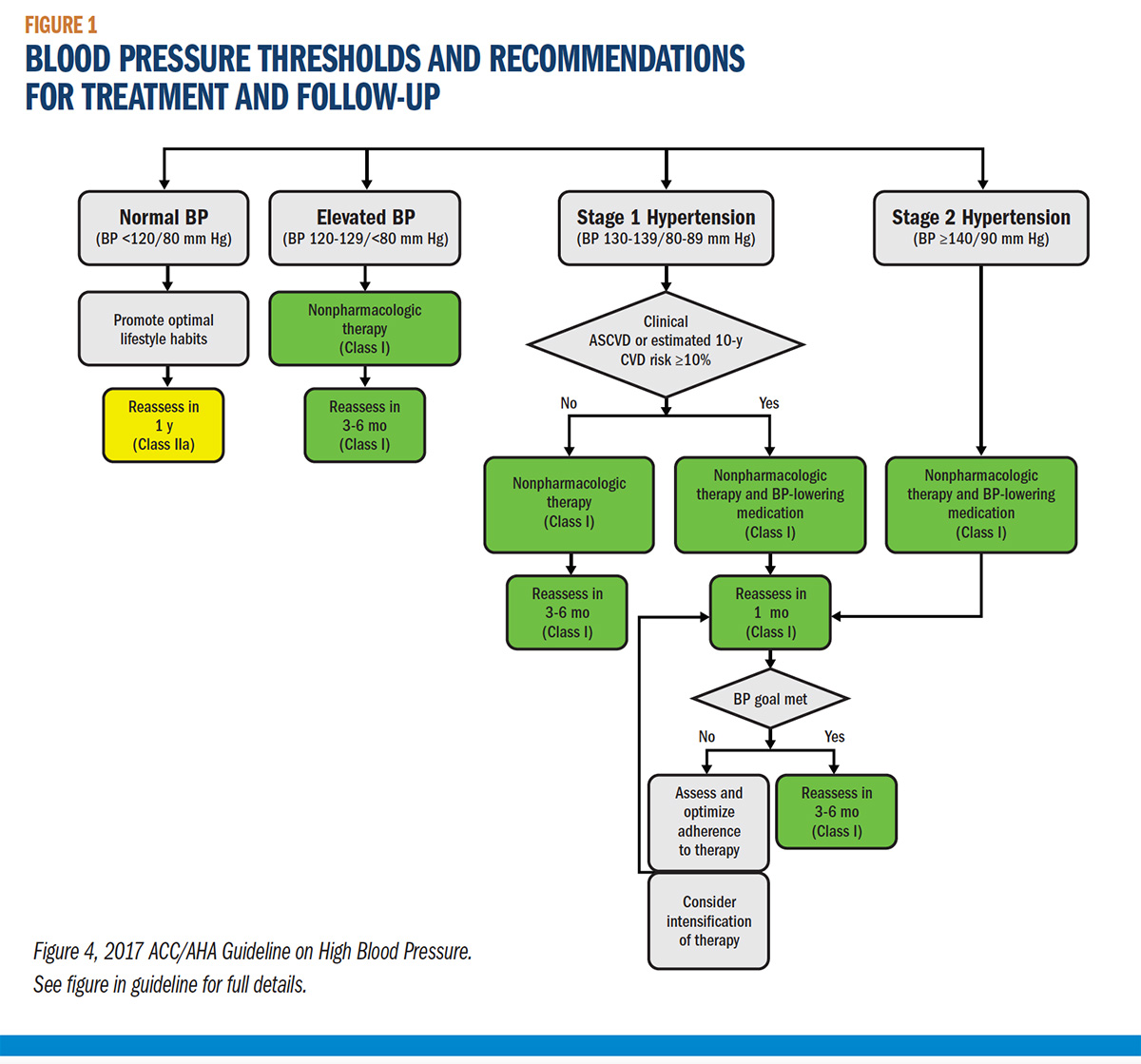

The threshold for treatment is determined by the ASCVD risk assessment. “Determining ASCVD risk provides a sharper way to define which patients with stage 1 hypertension are likely to benefit from pharmacologic therapy,” says Whelton. Using a combination of the absolute cardiovascular risk and BP level is more efficient and cost-effective to reduce risk than using only the BP level. For the vast majority of patients with stage 1 hypertension, the initial recommended action is one or more nonpharmacological interventions. The treatment algorithm for BP thresholds and recommendations for treatment and follow-up is shown in Figure 1.

“The 2017 Guideline has risk-based treatment recommendations, with lower targets for greater clinical benefit,” says Sondra M. DePalma, MHS, PA-C, CLS, AACC, a member of the Writing Committee and representative of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. She views this as a natural evolution as the evidence base for cardiovascular risk reduction grows and of guidelines per se.

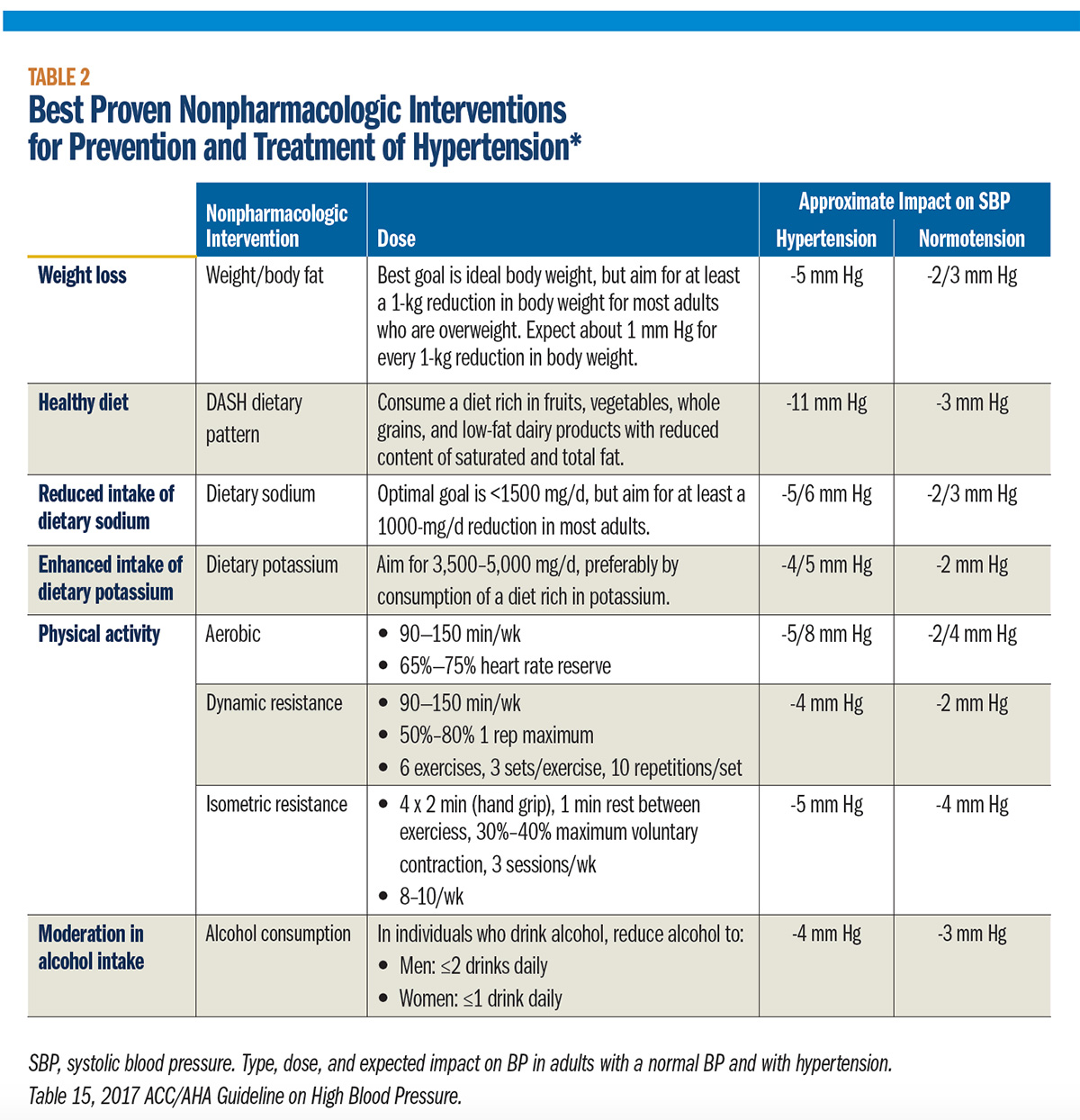

“Lifestyle changes will be the treatment approach for most patients who’ll now be considered to have stage 1 hypertension,” DePalma adds. These changes are detailed in the guideline and include weight loss, consuming a heart healthy diet, sodium reduction, potassium supplementation, increased physical activity and limiting alcoholic drinks (Table 2).

Lowering BP should be the central goal of antihypertensive therapy. The new guideline recommends more intensive therapy and a lower target for BP, especially in those at high risk for ASCVD. When pharmacologic therapy is needed, the guideline recommends agents from four drug classes (thiazide diuretics, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers) as options in adults who have no compelling need for choice of BP-lowering therapy for a comorbidity such as a recent heart attack or heart failure.

The external review committee found that thiazide diuretics, especially the long-acting thiazide-type drug chlorthalidone, are the best first-line agents for treatment of hypertension. However, based on their review of the entire literature, the Writing Committee felt there were only limited differences in efficacy among the four classes of antihypertensive drugs, says Whelton. Most adults with hypertension require more than one agent and specific combinations shown to be most effective are noted. Two first-line drugs of different classes are recommended for patients with stage 2 hypertension and average BP of 20/10 mm Hg above the BP target. Improved adherence can be achieved with once-daily drug dosing, rather than multiple dosing, and with combination therapy.

Beyond the Numbers

“The 2017 Guideline for High Blood Pressure is a comprehensive tool to guide care,” says Cheryl Dennison Himmelfarb, RN, ANP, PhD, a member of the Writing Committee and representative of the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. The document is a resource for physicians and all members of the cardiovascular care team. The content is provided in modular sections, each with its own references. “These knowledge chunks are ideal for point of care support,” adds DePalma.

“The bottom line is that we’re not meeting the goals of treatment,” says Dennison Himmelfarb. “A new guideline is an opportunity to review how well you and your system are serving your patients and retool,” she adds.

A systems-based approach is needed to identify patients not at goal, among other factors, along with measuring performance. A section on performance measures and quality improvement is included in the guideline. Along with an investment in physical resources such as the electronic health record, this also requires an investment in human resources to ensure every member of the care team has the necessary skills to improve care.

Additionally, the guideline recommends a structured, team-based approach with a dedicated section in the document. The guideline details the responsibilities and roles of the team and the members of the team. The patient is a key member of this team and shared decision making is an important component of optimizing management. The guideline also recognizes this approach often requires organizational change and reallocation of resources. Along with the electronic health record, clinical decision support such as treatment algorithms provided in the guideline, technology-based remote monitoring and self-management support tools for patients provide important assistance to the team.

“Even the most sophisticated health system may not be as robust as it could be to assist at the point of care,” states Dennison Himmelfarb. And electronic health records may not be optimized to support hypertension care, because they’ve largely been developed since JNC 7, notes Carey. This is a good opportunity to add treatment algorithms from the 2017 guideline and flags to alert providers of patients not at goal.

Other health information technologies to be optimized are patient registries (recommendations for how to use them are provided) and telehealth to monitor BP, which can reduce the costs and increase the quality of care.

Every patient with hypertension should have a clear, detailed and current evidence-based plan of care that ensures the achievement of treatment and self-management goals, effective management of comorbid conditions, timely follow-up with the health care team and that adheres to guideline-directed management and therapy for cardiovascular disease. A table with the evidence-based elements of this care is included in the guideline. A sequential flow chart for management of hypertension is another tool for improving the systems of care.

Adherence is a perennial issue and tackled in the guideline, along with strategies to detect lack of adherence. A handy tool is the table listing barriers at the patient and provider/system level and improvement strategies. “The section on resource-constrained patients is a must-read for every member of the cardiovascular care team,” says Carey, to learn about strategies to help this large and perhaps growing population of patients.

Hypertension Care for Special Populations

“Health disparities in hypertension continue,” notes Dennison Himmelfarb. Providers must be aware there are disparities and monitor control rates overall and by race and by sex. This provides the data required to strategically address disparities in your practice or system.

Additionally, all providers should be aware of the differences in the prevalence and control rates by racial-ethnic groups, and differences by sex within these groups, and the differential impact of hypertension on their morbidity and mortality.

Hispanic Americans, a diverse group with different rates of hypertension and its consequences in relation to their ancestry, have more comorbid cardiovascular risk factors compared with whites and African Americans. Lack of awareness and treatment in Hispanic Americans contributes to their lower control rates. African Americans have a similar rate of awareness and treatment as whites, but hypertension is more severe and agents are less effective, leading to lower control rates. At all ages, African Americans have a have a higher level of BP – and they have hypertension at younger ages.

“The new classification of blood pressure levels will most likely have the greatest impact on African Americans, compared with any other special population,” says Kenneth A. Jamerson, MD, a member of the Writing Committee and representative of the Association of Black Cardiologists.

Along with the new classification, the focus on risk assessment will mean that more African Americans will receive treatment at a younger age. “This earlier treatment in African Americans brings a greater potential impact for reducing their cardiovascular risk,” adds Jamerson.

"The bottom line is that we’re not meeting the goals of treatment. A new guideline is an opportunity to review how well you and your system are serving your patients and retool." — Cheryl Dennison Himmelfarb, RN, ANP, PhD

The 2017 guideline recommends the initial treatment for African Americans adults with hypertension but without heart failure or chronic kidney disease, including those with diabetes, should be a thiazide-type diuretic or calcium channel blocker. Two or more antihypertensive medications are recommended to achieve a BP target <130/80 mm Hg in most adults with hypertension, especially in African Americans.

The prevalence of hypertension is lower in women compared with men until about the fifth decade, but is higher later in life. While no randomized controlled trials have been powered to assess outcomes specifically in women (e.g., SPRINT), other than special recommendations for management of hypertension during pregnancy, there is no evidence the BP threshold for initiating drug treatment, treatment target, choice of initial antihypertensive medication or combination of medications for lowering BP differs for women compared with men.

What’s in it for Cardiologists?

In the complex patients that cardiologists see every day, managing their hypertension is instrumental to “preventing a downward slope in their patient’s health status and improvement in their quality of life,” says Whelton. For many of these patients, this means achieving personal goals like attending a family wedding or even staying out of the hospital or a nursing home. The guideline provides the road map.

The detailed information about the properties of antihypertensive drugs in the document is a reference for cardiologists. Treatment algorithms provide a step-by-step approach to evaluating secondary causes of hypertension and managing chronic kidney disease, as well as patients with a history of stroke and acute ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage.

Detailed recommendations and supporting text is provided for the management of hypertension in patients with stable ischemic heart disease, heart failure, renal transplant, diabetes or metabolic syndrome, atrial fibrillation, valvular disease or aortic disease.

Risk assessment is the cornerstone of the 2017 guideline for high blood pressure and the basis for decision making. Risk assessment is second nature for cardiologists and members of the cardiovascular care team. “Thus, cardiovascular professionals have a responsibility and role in disseminating the guideline to primary care providers and helping them to understand the rationale and the evidence,” says Carey. Another role is helping with understanding risk assessment and incorporating it into practice.

The Takeaways

The classification of blood pressure and definition of hypertension has changed, resulting in a larger proportion of the U.S. population being diagnosed as having hypertension. Nonpharmacologic therapy – lifestyle changes – will be the recommended treatment for the majority of the newly diagnosed patients with hypertension. Formal assessment of 10-year ASCVD risk drives treatment thresholds and targets. For most patients with hypertension, greater intensity of treatment and a lower BP treatment target are recommended. Reliance on team-based care and implementation of recommended practice and health system changes will be important to meet the goals of the guideline.

Tweet this article: Tweet

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Advisory Committees, African Americans, Algorithms, American Heart Association, Angiotensin Receptor Antagonists, Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors, Antihypertensive Agents, Aortic Diseases, Atrial Fibrillation, Atrial Natriuretic Factor, Blood Pressure, Calcium Channel Blockers, Cardiovascular Diseases, Cerebral Hemorrhage, Chlorthalidone, Comorbidity, Counseling, Decision Making, Decision Support Systems, Clinical, Diabetes Mellitus, Diastole, Diuretics, Electronic Health Records, Ethnic Groups, European Continental Ancestry Group, Exercise, Follow-Up Studies, Heart Failure, Heart Valve Diseases, Hispanic Americans, Hyperaldosteronism, Hypertension, Kidney Transplantation, Life Style, Masked Hypertension, Metabolic Syndrome, Myocardial Infarction, Myocardial Ischemia, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U.S.), Nursing Homes, Organizational Innovation, Patient Care Team, Peripheral Vascular Diseases, Physician Assistants, Point-of-Care Systems, Potassium, Pregnancy, Prehypertension, Prevalence, Primary Health Care, Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen, Quality Improvement, Quality of Life, Registries, Renal Insufficiency, Chronic, Risk Assessment, Risk Factors, Self Care, Sleep Apnea, Obstructive, Sodium, Sodium Chloride Symporter Inhibitors, Stroke, Systole, Telemedicine, Thiazides, Weight Loss, White Coat Hypertension, Writing

< Back to Listings