Feature | Health Policy Implications to Reduce Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

Maternal mortality is rising in the U.S. In fact, with a concerning ratio of 17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births, based on 2020 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. has the highest rate of maternal mortality among countries with comparably high sociodemographics.1,2

Cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular disease – the leading causes of maternal death, combined account for more than 33% of deaths. Notably, heart disease and stroke were the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths from 2011-2017 and in 2020 this continues to be the case. Most importantly, these deaths are largely preventable, with some 70% of the maternal deaths related to cardiovascular disease preventable with risk factor modification.1

Disparities in Maternal Outcomes

Key factors that contribute to cardiovascular-driven maternal morbidity and mortality include high rates of unplanned pregnancy, inconsistent access to care and health insurance, rising rates of chronic diseases such as obesity, hypertension and diabetes, as well as advanced maternal age in women of child-bearing age.1,2

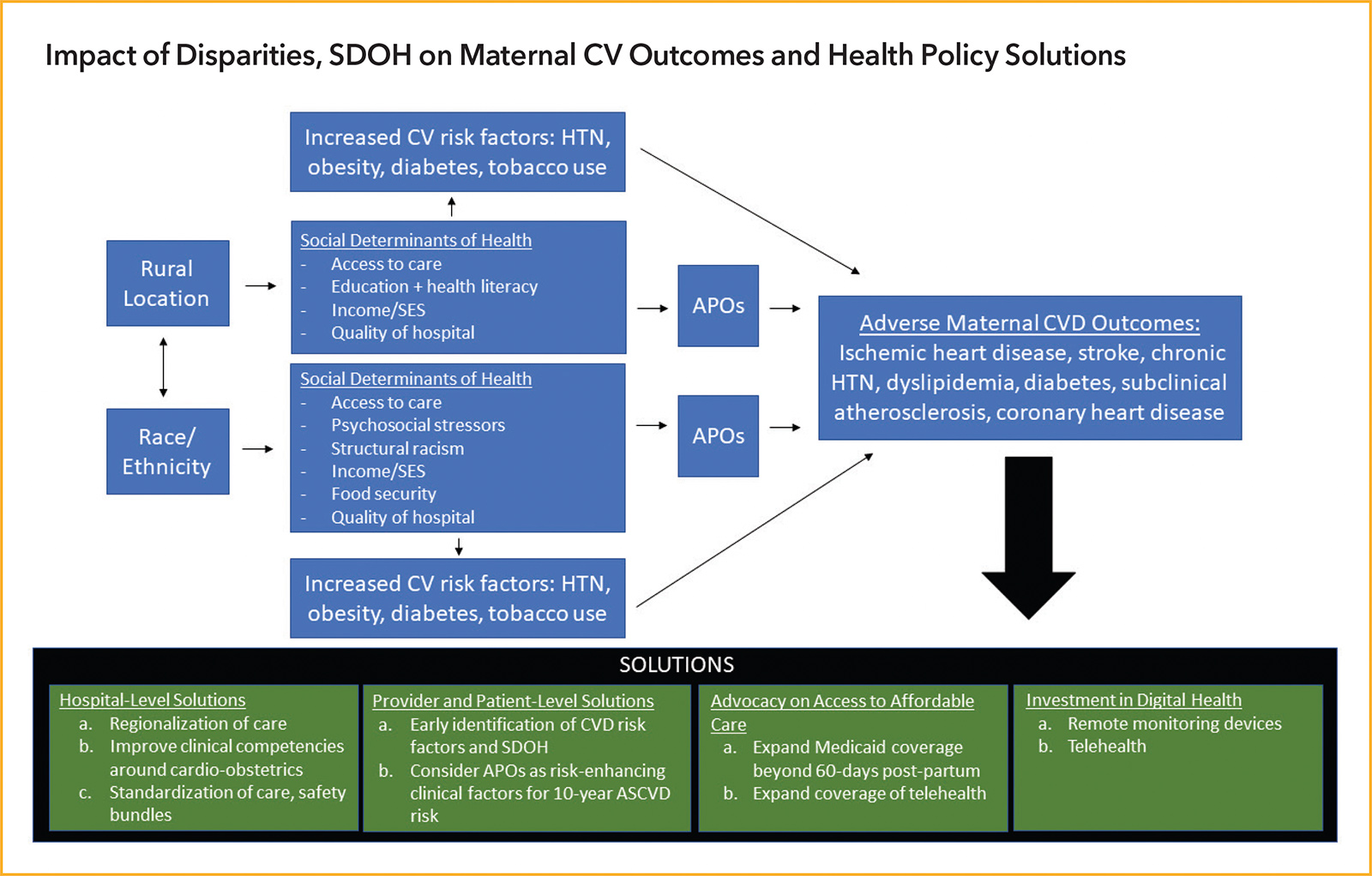

Striking disparities exist in maternal outcomes in the U.S. A strong body of literature reveals that racial/ethnic and rural/urban disparities contribute to adverse cardiovascular outcomes in pregnancy and beyond, often mitigated by adverse sociodemographic factors.

Black women, compared with White women, have a substantially higher risk for:2

- Mortality (odds ratio [OR], 1.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.21-1.73)

- Myocardial infarction (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.06-1.42)

- Stroke (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.41-1.74)

- Pulmonary embolism (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.30-1.56)

- Peripartum cardiomyopathy (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.66-1.76).

Moreover, insurance coverage, or the lack of it, has an impact on maternal outcomes. Among Black, Indigenous (Native American or Alaskan Native) and rural women, compared with White women and urban women, there's a high rate of births that are funded by Medicaid. This is significant because in states that do not have Medicaid expansion, health insurance coverage ends 60 days postpartum, despite data showing that cardiovascular disease-related deaths contribute to the largest cause of pregnancy-related deaths from Days 42 to 365 postpartum.1,2

Higher rates of comorbidities are present in women who live in rural areas and/or are from racial/ethnic minority groups, increasing their risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes.1,2 These comorbidities include diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity and smoking.

There are also significant disparities in adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs), which include hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension), preterm delivery, gestational diabetes, small-for-gestational-age delivery, placental abruption and pregnancy loss.1,2 A growing body of evidence shows these APOs are associated with an increased risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease.1,2

The relative risk for APOs, based on a recent analysis of data from the National Center for Health Statistics, is higher in several racial/ethnic groups compared with non-Hispanic White women: 1.15 (95% CI, 1.13-1.18) for Hispanic women, 1.78 (95% CI, 1.74-1.82) for Asian/Pacific Islander women and 0.97 (95% CI, 0.94-0.99) for non-Hispanic Black women.1

Gestational diabetes rates were the highest in Asian Indian participants in a recent study reported by Shah, et al, with a relative risk of 2.24 (95% CI, 2.15-2.33).3

Studies have also documented higher rates of preeclampsia among non-Hispanic Black women, and disproportionately higher rates of death from complications of preeclampsia compared with their non-Hispanic White counterparts.1

Severe Maternal Morbidity and Early Warning Triggers

Two Federal Bills Moving Maternal Health Forward

Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2021. This Act builds on existing legislation to comprehensively address every dimension of the maternal health crisis in America. Click here to learn more and support this bill.

Mothers and Offspring Mortality and Morbidity Awareness Act. The MOMMA's Act will improve data collection, disseminate information on effective interventions and expand access to health care and social services for postpartum women. In addition, the bill would expand coverage for postpartum care for up to one year under Medicaid and CHIP. This bill is supported by the American Medical Association. Click here to learn more and support this bill.

Another important maternal outcome to recognize is severe maternal morbidity (SMM), which remains poorly defined, but encompasses unexpected outcomes of labor and delivery. These include significant cardiovascular consequence such as myocardial infarction, aneurysm, cardiac arrest, heart failure and cerebrovascular disorders.1 Like maternal mortality, SMM is preventable and several in-hospital measures and safety initiatives can help reduce it.

SMM is much more common than mortality. For every maternal death, 100 women suffer a severe obstetric morbidity, a life-threatening diagnosis or undergo a lifesaving procedure during their delivery hospitalization.1 SMM affects >60,000 women annually in the U.S., and this number has been on the rise over the last few decades with similar rural and racial disparities.1

In fact, Black women have the highest rates for 22 of 25 indicators of severe morbidity from SMM.1 Data have consistently shown that hospitals which perform higher numbers of deliveries of Black or Hispanic infants (>50% or hospitals with highest quartile of proportions of minorities) disproportionately have higher risk adjusted SMM rates compared with hospitals primarily serving lower rates of Black or Hispanic patients. Studies have also consistently found higher pregnancy-related mortality risks in Black women, even when controlling for factors such as insurance coverage, marital status and medical conditions.1

There is a profound disadvantage identified among Indigenous women residing in rural counties, with two-thirds living in counties with median incomes in the bottom national income quartile. Indigenous women residing in rural counties also have the greatest risk for preexisting, chronic conditions complicating childbirth, including diabetes and substance use disorders.

SDOH and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines social determinants of health (SDOH) as "conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age." This framework has been used extensively in health care disparities research and has increasingly been recognized and tied to APOs and maternal inequities.1 This framework includes factors such as economic stability and socioeconomic status, neighborhood and physical environment, transportation, education, health literacy, food security, racial discrimination, psychosocial stressors and insurance coverage.1

Importantly, SDOH such as socioeconomic disadvantages, poor health literacy, transportation barriers, lack of access to adequate health care, food insecurity and psychosocial stressors have cascading effects on APOs and downstream cardiovascular health. These SDOH are also deeply intertwined with and are compounded by existing racial and rural disparities.

Health Policy Implications to Bridge the Gap and Reduce Adverse Outcomes

A recent policy statement on maternal health from the American Heart Association provides strategies to reduce overall deaths and address racial disparities in maternal health through a three-pronged approach focused on patients, health care providers and care systems. This approach includes:

- Addressing disparities and inequities by educating providers, improving reporting of maternal outcomes, expanding Medicaid funding in states where it doesn't exist and increasing public awareness about activities to reduce heart disease (such as smoking cessation). Teaching health equity curricula in medical school and addressing SDOH by developing EMR-based metrics on how to report SDOH.

- Increasing multidisciplinary care with early detection, prompt management and close and extended follow-up. Cardio-obstetric programs are much needed for obstetricians, gynecologists and maternal-fetal medicine colleagues to work closely with adult cardiologists, adult congenital heart disease cardiologists, advanced heart failure specialists, patient navigators and coordinators, advanced nursing practitioners, critical care and obstetric anesthesia, and genetic counselors to provide this multidisciplinary care.

- Modernizing maternal health care delivery by informing women of preconception counseling, expanding postpartum care for Medicaid participants to the first year after delivery and transforming provider payment to prioritize high quality, low cost and eliminate unnecessary services. This would support Medicaid expansion in all 50 states and support legislation extending Medicaid from 60 days postpartum to a full year. Elevate guidelines for continued monitoring for latent development of hypertension, cardiovascular disease and stroke in clinical practice. It also supports access to postpartum care that assesses physical, social and psychological well-being. Finally, these guidelines improve health literacy of the patients and their families to identify early warning tools and promote preventive care through Life's Simple 7 metrics.

- Updating technology and systems by modernizing the public health care infrastructure in under-resourced communities and closing the gaps between health care in urban and rural areas. Improving digital health and remote monitoring.

- Quality reporting of maternal outcomes and health metrics. The policy statement supports robust individual state maternal mortality review committees and standardizes quality measures for maternal morbidity and mortality.

While federal legislation is extremely important for large-scale policy, state-level policy will govern the health care coverage for prepregnancy and postpartum care in nearly half of all women who become pregnant. While historically the care of the majority of cardiac patients has been funded by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and ACC advocacy efforts have been targeted at the federal level, our efforts at the state level will need to be redoubled now that cardiac care is increasingly required in pregnant/postpartum women and ongoing telehealth coverage will help advance such care. We urge cardiologists to partner with their state societies and work together to improve maternal health in their state.

This article was authored by Lochan Shah, MD, internal medicine resident at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD; Laxmi S. Mehta, MD, FACC, vice chair of wellness, Department of Internal Medicine, section director of Preventative Cardiology and Women's Cardiovascular Health, director of lipid clinics, Sarah Ross Soter Endowed Chair in Women's Cardiovascular Health, and professor of medicine at The Ohio State University in Columbus; Colleen M. Harrington, MD, FACC, assistant professor of medicine, associate program director of the cardiology fellowship program, and co-director of the Women's Cardiovascular and Pregnancy Clinic at the University of Massachusetts School of Medicine in Worcester, and adjunct assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; Malissa J. Wood, MD, FACC, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and co-director, Corrigan Women's Heart Health Program, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston; and Garima Sharma, MD, FACC, assistant professor of medicine, associate vice chair for Women's Careers in Academic Medicine, director of cardio-obstetrics, and associate director of preventive cardiology-education at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Mehta is chair of ACC's Board of Governors Wellness Work Group. Harrington is governor-elect of the Massachusetts ACC Chapter. Wood is a Trustee of the ACC, chair-elect of the ACC Board of Governors and governor of the Massachusetts ACC Chapter. Sharma is governor of the ACC Maryland Chapter.

References

- Shah LM, Varma B, Nasir K, et al. Reducing disparities in adverse pregnancy outcomes in the United States. Am Heart J 2021;2:S0002-8703(21)00225-8.

- Mehta LS, Sharma G, Creanga AA, et al. Call to action: Maternal health and saving mothers: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021;Sep 8:[Epub ahead of print].

- Shah NS, Wang MC, Freaney PM, et al. Trends in gestational diabetes at first live birth by race and ethnicity in the US, 2011-2019. JAMA 2021;326:660-9.

COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Pregnant Women: What Can OB/GYNs and Cardiologists Do Together?

As new data continue to evolve on the severity of COVID-19 infection in pregnant women and its effects on adverse pregnancy outcomes, cardiologist and obstetricians have a renewed responsibility towards addressing these concerns along with other cardiovascular and obstetric questions. In our communities across the country, there's much hesitancy about this vaccine, and it's no different among women who are pregnant.

In fact, obstetric consultants and practitioners can attest to the self-discontinuation of needed and chronically taken cardiovascular, rheumatologic and immunosuppressive medications at conceptus by newly pregnant patients. Thus, this "medication hesitancy" has evolved into the vaccine hesitancy we see today among pregnant women.

Pregnant women often have concerns about the impact of the vaccine, as well as other medications, and many of these concerns come from myths and misunderstanding. However, it is important to address the concerns of pregnant women about the effects of COVID-19 with an intent for an informed evidence-based decision.

Owing to the paucity of clinical trials involving pregnant women, clinicians nearly always must rely on registry or retrospective observational data regarding the use of medications, therapies and even vaccines. The COVID-19 vaccine is no different.

A study published last month in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology showed that COVID-19 infection during pregnancy, compared with no infection, is strongly associated with preeclampsia (8.1% vs. 4.4%; relative risk, 1.8; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.32-2.61), especially among nulliparous women (risk ratio, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.17-3.05).1 Preeclampsia is a well-recognized cardiovascular risk factor in women and should be part of prepregnancy counseling. Additionally, pregnant women and those with existing cardiovascular conditions such as diabetes, obesity, chronic hypertension, cardiomyopathy, etc., are at increased risk of severe illness from COVID-19 compared with nonpregnant women.

Additionally, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions in pregnant women with COVID-19 are higher. Data from a recent study published in JAMA Network Open showed that compared with nonpregnant women, pregnant women were more frequently admitted to an ICU (10.5 vs. 3.9 per 1,000 cases; aRR, 3.0; 95% CI, 2.6-3.4), received invasive ventilation (2.9 vs. 1.1 per 1,000 cases; aRR, 2.9; 95% CI, 2.2-3.8) and received mechanical circulatory support (0.7 vs. 0.3 per 1,000 cases; aRR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.5-4.0). The data reflect a 70% increased risk for death associated with pregnancy in this population (aRR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2-2.4). Irrespective of pregnancy status, ICU admissions, receipt of invasive ventilation and death occurred more often among women aged 35-44 years and was higher in Black and Hispanic women.2

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that pregnant and breastfeeding women get a COVID-19 vaccine.3,4 It is important that as obstetric consultants and providers we address the uncertainty and hesitancy for the COVID-19 vaccine in our pregnant patients. ACOG and SMFM have provided guidance to assist in these conversations.5-7 In doing this, we may also address concerns of other "medication hesitancy" that has troubled this specialized population for decades. The hope is this susceptible and medically vulnerable population is able to make an informed decision for themselves and their families.

This article was authored by Garima Sharma, MD, FACC, and Arthur J. Vaught, MD, director of Labor and Delivery at Johns Hopkins Hospital and assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

References

- Papageorghiou AT, Deruelle P, Gunier RB, et al. Preeclampsia and COVID-19: results from the INTERCOVID prospective longitudinal study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021;225:289.e1-289.e17.

- Chinn J, Sedighim S, Kirby KA, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of women with COVID-19 giving birth at US academic centers during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(8):e2120456.

- ACOG and SMFM Recommend COVID-19 Vaccination for Pregnant Individuals. Available here. Accessed Sept. 28, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccines While Pregnant or Breastfeeding. Available here. Accessed Sept. 28, 2021.

- COVID-19 Vaccines and Pregnancy: Conversation Guide for Clinicians. Available here. Accessed Sept. 28, 2021.

- ACOG Practice Advisory. COVID-19 Vaccination Considerations for Obstetric-Gynecological Care. Available here. Accessed Sept. 28, 2021.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Provider Considerations for Engaging in COVID-19 Vaccine Counseling With Pregnant and Lactating Patients. Available here. Accessed Sept. 28, 2021.

Clinical Topics: Prevention, Vascular Medicine, Hypertension

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Pregnancy, Maternal Death, Maternal Mortality, Pregnancy, Unplanned, Maternal Age, Diabetes Mellitus, Cerebrovascular Disorders, Hypertension, Stroke, Insurance, Health, Obesity, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S., Health Services Accessibility

< Back to Listings