Blood Pressure (BP) and Diabetes:

Elevated BP may be associated with increased risk of diabetes, according to Connor A. Emdin, HBSc, et al. In a prospective analysis of 4.1 million patients without vascular disease or diabetes, 20 mmHg higher systolic BP was found to be associated with a 58 percent higher risk of diabetes, while a 10 mmHg higher diastolic BP was associated with a 52 percent higher risk. “These investigators offer an exceptionally rigorous evaluation of the relation between BP and incident diabetes,” states Donna K. Arnett, MSPH, PhD, in an accompanying editorial comment. “This study provides a strong rationale for continued research into the biological basis and pharmacological implications of the observed association.”

Smoking Cessation:

An analysis of medical costs associated with atherosclerotic lower extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD) found that health care costs in one year were $18,000 higher in smokers with PAD than non-smokers with the condition. Accordingly, smokers may be more likely to be hospitalized for leg events, heart attack and coronary heart disease related to atherosclerotic PAD than non-smokers with PAD. In an accompanying editorial, Geoffrey D. Barnes, MD, MSc, FACC, and Elizabeth Jackson, MD, MPH, FACC, note the study highlights the urgent need for smoking cessation among PAD patients and that getting patients to quit may improve care and save significant health dollars over the long term.

Impact of Childhood Stress:

A 45-year study of nearly 7,000 people born in a single week in Great Britain in 1958 found psychological distress in childhood – even when conditions improved in adulthood – may be associated with higher risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes later in life. “This study supports growing evidence that psychological distress contributes to excess risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disease and that effects may be initiated relatively early in life,” says lead author Ashley Winning, ScD, MPH. “Early prevention and intervention strategies focused not only on the child but also on his or her social circumstances may be an effective way to reduce the long-lasting harmful effects of distress.” In an accompanying editorial comment, E. Alison Holman, PhD, FNP, explains that it may not be helpful for clinicians to focus on “managing” known cardiovascular disease risk factors like smoking, obesity, elevated cholesterol and lack of exercise without addressing underlying risk factors that affect patients.

Global Food Consumption:

More than 80 percent of cardiovascular disease deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, but very little data on the impact of diet on cardiovascular disease exists from these countries. A state-of-the-art review summarizes the evidence relating food to cardiovascular disease and how the global food system contributes to dietary patterns that greatly increase the risks for populations with poor health. The authors identify what an optimal diet for reducing cardiovascular disease looks like – giving the traditional Mediterranean diet as an example – and suggest that it may be possible to recreate this diet in other regions using appropriate similar food replacements based on food availability and preferences.

Fructose and Cardiometabolic Health:

There is compelling evidence that drinking too many sugar-sweetened beverages, which contain added sugars in the form of high fructose corn syrup or sucrose, can lead to excess weight gain and a greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, according to a research letter by Vasanti S. Malik, ScD, and Frank B. Hu, MD, PhD. The study – the most comprehensive review of the evidence on the health effects of sugar-sweetened beverages to date – also takes a closer look at the unique role fructose may play in the development of these conditions.

Achieving Ideal Cardiovascular Health:

Promotion of a healthy diet and physical activity will likely help in achieving the ideal cardiovascular health goals set by the American Heart Association, according to a research letter from Adnan Younus, MD, et al. In a review of 18 studies related to cardiovascular health metrics, researchers found that diet metrics were suboptimal, while BP and body mass index (BMI) metrics reported less than 50 percent. Focusing efforts on promotion of healthy diet and exercise may indirectly influence BMI, BP and fasting glucose metrics, according to the authors.

Early Healthy Lifestyle Intervention:

Introducing healthy lifestyle behaviors to children in preschool may improve their knowledge, attitude and habits toward a healthy diet and exercise, and may lead to reduced levels of body fat, according to Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, MACC, editor-in-chief of JACC, who was an author of the study. Through the SI! Program, researchers in Madrid implemented a three-year healthy lifestyle intervention for three to five year olds that used their school, teachers and families to promote cardiovascular health through healthy diet, increased physical activity, understanding of the human body and managing emotions. “We need to focus our care in the opposite stage of life – we need start promoting health at the earliest years … in order to prevent cardiovascular disease,” states Fuster. (See related article, above) In a related editorial comment, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, FACC, et al., says the program is groundbreaking, and follow-up studies to further pinpoint the exact mechanisms by which the program achieved positive effects on young children’s health will be vital for implementing the program in other areas and informing the design of future global programs.

Risk Factor Management:

Three cross-sectional surveys of EUROASPIRE show challenges in applying prevention guidelines in clinical practice for acute coronary artery disease patients, according to a research letter from Kornelia Kotseva, MD, PhD, et al. The results of the surveys show increases in obesity and diabetes amongst the patients, while the proportion of persistent smokers remained the same. “The life-saving treatments for acute coronary artery disease … must be matched by modern preventive cardiology programs combining a professional lifestyle intervention with effective risk factor control to reduce total cardiovascular risk,” states Kotseva.

Read the full JACC Population Health Promotion issue at OnlineJACC.org.

Reference

- J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(14).

Population Health and Early Career Professionals:

Personalized lifestyle counseling is a skill all fellows in training and early career professionals should learn, according to Joshua Schulman-Marcus, MD, in the issue’s Fellows in Training and Early Career Column. He notes that communicating with patients and families on lifestyle changes has the potential to prevent cardiovascular disease. “Fellows should be offered the opportunity to work with and get advice from nurse practitioners and other health team members, many of whom have deep experience in counseling patients,” comments Schulman-Marcus. “Cardiologists must continue to provide support and resources

for behavioral change without judgment and provide this care with

consistent emphasis on the critical importance of the patient’s efforts,”

states Pamela Morris, MD, FACC, chair of ACC’s Prevention of

Cardiovascular Disease Section, in a response.

|

|

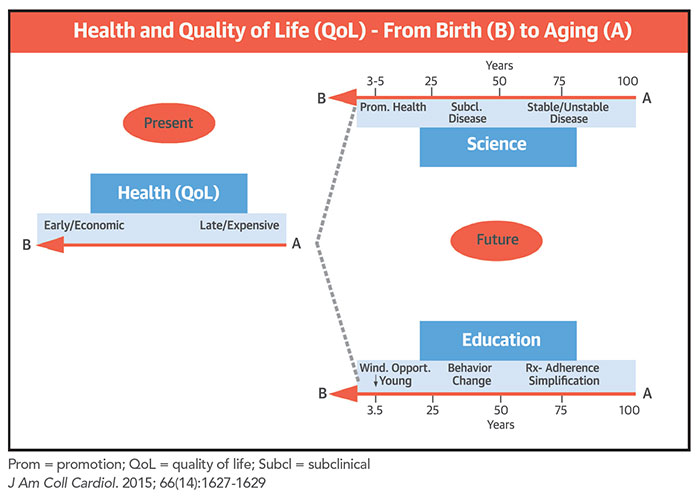

When we are trying to establish goals toward improved cardiovascular health or health promotion on a population-wide scale, it is important to remember that we need unique strategies at different stages of our lives, depending on the varied scientific/physiopathological background and educational/behavioral tools appropriate for each stage.

When we are trying to establish goals toward improved cardiovascular health or health promotion on a population-wide scale, it is important to remember that we need unique strategies at different stages of our lives, depending on the varied scientific/physiopathological background and educational/behavioral tools appropriate for each stage.