Menopause Hormone Therapy: What a Cardiologist Needs to Know

Cardiologists are frequently consulted regarding menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) benefits and risks in women with menopausal symptoms. Observational studies from the 1980s and 1990s consistently reported that HRT (hormone replacement therapy) reduced the incidence of cardiovascular and many other diseases and the majority of US women were prescribed these preparations, now termed MHT. Hormone users tended to be healthier, wealthier and to have fewer traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Large randomized controlled trials a decade later, the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) in women with established coronary disease and the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) study in healthy women (estrogen for women after hysterectomy and estrogen + progestin in women with a uterus) proved otherwise.1,2 In the WHI data, MHT provided no evidence for the primary or secondary prevention of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, angina or myocardial revascularization. The 2015 Cochrane Database analysis comparing MHT with placebo provided risk data; MHT use was associated with an additional six strokes per 10,000 women (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.10-1.41), 8 cases of VTE per 10,000 women (RR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.36-2.69), and four cases of pulmonary embolism (PE) per 10,000 women (RR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.32-2.48).3 Long-term mortality for MHT from the WHI disclosed no increased risk of all-cause mortality, CVD mortality or cancer mortality during 18 years of follow-up for women taking conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg/d alone for a median of 7.2 year or for women taking CEE 6.25 mg/d plus medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5 mg/d for a median of 5.6 years.4 Most contemporary recommendations for MHT are limited to low risk women less than 10 years since the onset of menopause and under the age of 60 years, a different population from WHI women who were on average several years post-menopause. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS), the American College of Endocrinology, and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) also identified that MHT is neither beneficial nor indicated for preventing or reducing CVD.5-7

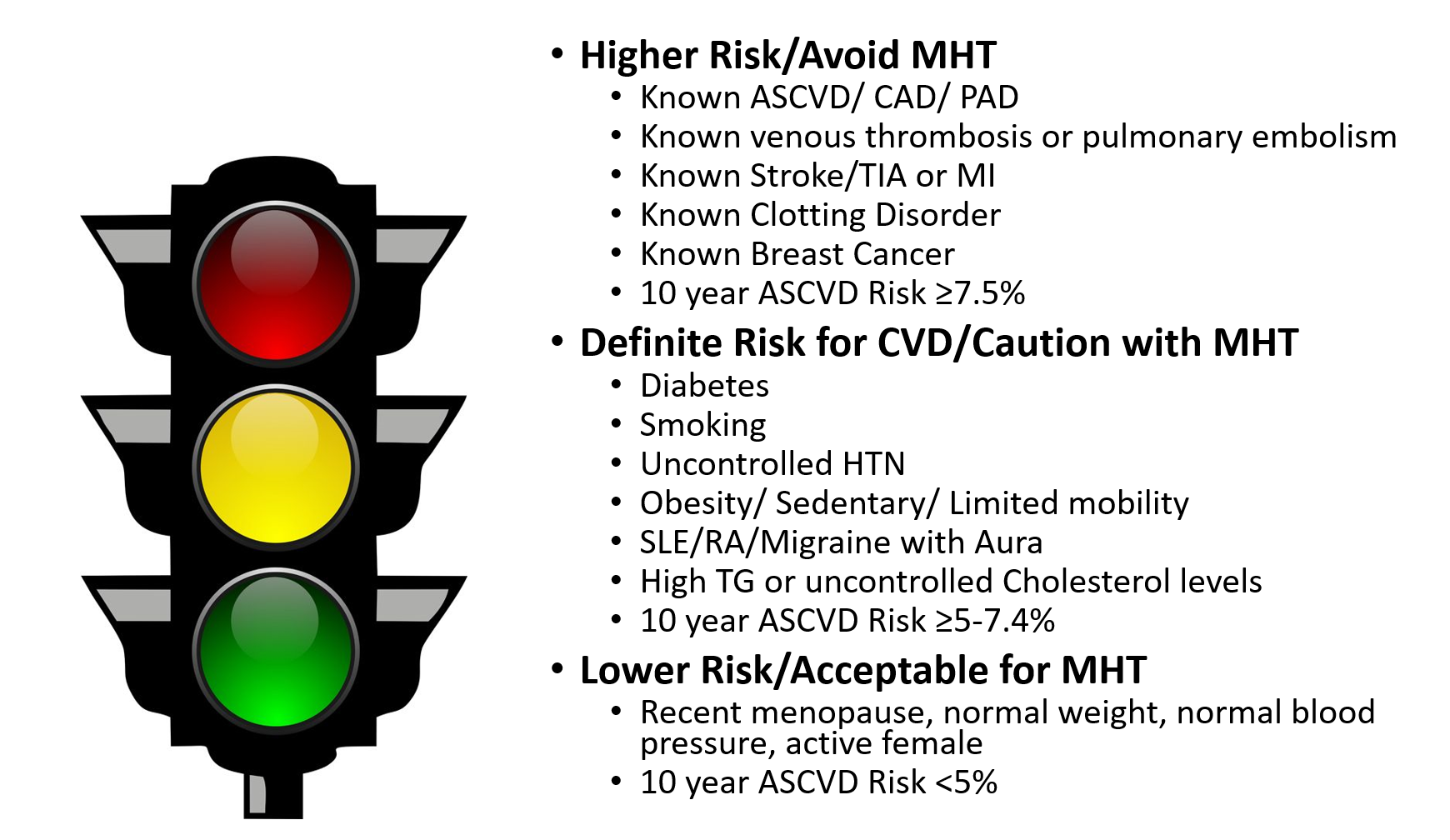

Nonetheless, many women experience severe menopausal symptoms that affect their quality of life, develop unfavorable biomarkers (insulin, lipids, fibrinogen, plasminogen and CRP) and report unpleasant physical effects from menopause. MHT remains the most effective treatment for significant vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). The 2017 NAMS Position Paper outlines an individual approach to CVD risk assessment and recommends low dose MHT for short periods of time for management of severe menopause symptoms.5 Figure 1 illustrates an approach to assess women for MHT based on their individual CVD risks.

Figure 1: Assessing Women for Menopausal Hormone Therapy

The American Heart Association (AHA), the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and NAMS support an individualized risk assessment for women considering MHT, rather than an absolute recommendation. The atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) pooled-cohort equation risk calculator is useful for assessing a woman's risk of CVD over the next 10 years and for her lifetime.8 While many argue that the ASCVD Risk Calculator underestimates risk in women because it only includes traditional CVD risk and not unique risk characteristics in women, it is useful for overall risk assessment and for patient education. A recent joint Presidential Statement from the ACC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends individual CVD risk assessment at all well-woman visits and use of the pooled-cohort equation.9 CVD risk assessment should additionally include a history of pregnancy complications, particularly hypertension, preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, and rheumatologic/ chronic inflammatory disorders in addition to traditional CVD risk factors such as smoking, high cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and metabolic syndrome.10 History of previous cancer treatment, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, high C-reactive protein and clotting disorders should be included in the assessment for risk of VTE as well as for CVD. The MHT paradox is that while hormone replacement has shown improvement in LDL-C, HDL-C, triglyceride levels and even insulin resistance, randomized controlled trials of MHT in postmenopausal women have failed to demonstrate any reduction in cardiovascular events.2

Newer studies have examined the timing of MHT initiation and the dosing and routes of administration of MHT. The timing hypothesis supports the theory that the beneficial effects of MHT in preventing atherosclerosis occur when therapy is initiated before ASCVD has developed. The KRONOS Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) evaluated 727 women ages 42 to 58 within 3 years of their final menstrual period randomized to placebo or oral conjugated equine estrogen (o-CEE) at 0.45 mg/d or transdermal Estradiol (t-E2) in a 50 μg/d patch, each with cyclic oral medroxyprogesterone 200 mg for 12 d/mo.11 Women were monitored yearly for biometrics and biomarkers. Early detection and progression of atherosclerosis was measured by carotid intimal media thickness (CIMT) and coronary artery calcification (CAC). After 3 years of follow-up, the o-CEE and t-E2 groups had neutral or favorable effects on blood pressure and CVD biomarkers and no adverse effects on CIMT or CAC. KEEPS revealed no adverse effects from low dose oral or transdermal MHT when started early after menopause. The Early vs. Late Postmenopausal Treatment with Estradiol (ELITE) study randomized 643 women to two timing groups, early treatment (less than 6 years from menopause) and late treatment (over 10 years since menopause onset).12 Both groups were treated with oral 17-beta Estradiol 1 mg/d plus progesterone vaginal gel 45 mg for 10 of 30 days. Follow-up included vital signs and biomarkers, CIMT every 6 months and CAC at baseline and at 5 years. The early treatment group had less progression of CIMT measurements and neither group showed a significant change in CAC scores. The early treatment group outcome suggested no harm and possible benefit with MHT. These two studies support that theory that early MHT treatment in low risk, younger women who seek reduction in their menopause symptoms may be safe.

Another important area of concern with MHT is increased venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk. Dose and route of administration are important for reducing VTE risk. A meta-analysis of trials of women who began MHT treatment within 10 years after menopause onset or younger than 60 years at MHT initiation indicated significant increase risk of VTE in the MHT group compared to placebo (RR 1.74; 95% CI, 1.11-2.73).3 Lower doses of oral MHT may have less VTE risk compared to higher doses. Micronized progesterone may have less VTE risk than other progestins.13 Limited observational data indicate less risk with transdermal MHT compared to oral MHT, but transdermal preparations increase breast density making mammography challenging. There is no evidence of increased risk of VTE with low dose estrogen vaginal gel for GSM. Cardiologists should use caution in women who smoke as the risk of DVT is increased with oral contraceptives as well in MHT.

A simple tool for assessing a women's risk with MHT is the NAMS MenoPro Mobile App.14 The app assists both the woman and her health care providers through an online algorithm that calculates the women's ASCVD risk using the pooled-cohort equation and asks questions about severity of menopause-related symptoms. The app provides lifestyle and nonmedical options as well as appropriate medical recommendations for prescription MHT and emails the patient the information specific to her individual responses and risks, facilitating shared decision-making. The free mobile app has published data on the clinical-decision support tool and includes the 2017 NAMS Position Statement on the app.13,5

Conclusion

While the WHI revealed no benefit and imparted increased risk for CVD in women on MHT after menopause, contemporary studies identify no increased CVD risk and some studies suggest improvement in biomarkers and imaging that evaluate early detection of CVD. These contemporary studies support initiation of MHT earlier after menopause and using low dose estrogen and transdermal MHT at the lowest feasible dosage and shortest duration. Counseling the postmenopausal women requires an assessment of her individual CVD risk and discussion on her quality of life and long-term follow-up. MHT initiated more than 10 years after menopause or after age 60 demonstrates less favorable benefits and greater absolute risk of CHD, stroke and venous thromboembolism. Postmenopausal women with known CVD or at high risk of CVD should be counselled on non-hormonal therapies. MHT is currently not recommended for CVD prevention for women of any age.

References

- Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA 1998;280:605-13.

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-33.

- Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD002229.

- Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality: the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2017;318:927-38.

- The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2018;25:1362-87.

- Cobin RH, Goodman NF, AACE Reproductive Endocrinology Scientific Committee. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology position statement on menopause-2017 update. Endocr Pract 2017;23:869-80.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2017;318:2224-33.

- Rana JS, Tabada GH, Solomon MD, et al. Accuracy of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk equation in a large contemporary, multiethnic population. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:2118-30.

- Brown HL, Warner JJ, Gianos E, et al. Promoting risk identification and reduction of cardiovascular disease in women through collaboration with obstetricians and gynecologists: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Circulation 2018;137:e843-52.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018. [Epub ahead of print]

- Taylor HS, Tal A, Pal L, et al. Effects of oral vs transdermal estrogen therapy on sexual function in early postmenopause: ancillary study of the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS). JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1471-9.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, et al. Methods and baseline cardiovascular data from the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol testing the menopausal hormone timing hypothesis. Menopause 2015;22:391-401.

- Canonico M, Alhenc-Gelas M, Plu-Bureau G, Olie V, Scarabin PY. Activated protein C resistance among postmenopausal women using transdermal estrogens: importance of progestogen. Menopause 2010;17:1122-7.

- Manson JE, Ames JM, Shapiro M, et al. Algorithm and mobile app for menopausal symptom management and hormonal/non-hormonal therapy decision making: a clinical decision-support tool from the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2015;22:247-53.

Clinical Topics: Anticoagulation Management, Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Care Team, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Prevention, Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism, Vascular Medicine, Anticoagulation Management and Venothromboembolism, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Hypertriglyceridemia, Lipid Metabolism, Nonstatins, Interventions and Vascular Medicine, Hypertension

Keywords: Primary Prevention, Secondary Prevention, Postmenopause, Menopause, Estradiol, Estrogens, Conjugated (USP), Progesterone, C-Reactive Protein, Medroxyprogesterone, Medroxyprogesterone Acetate, Risk Factors, Metabolic Syndrome, Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, Gestational, Contraceptives, Oral, Venous Thromboembolism, Insulin, Fibrinogen, Sedentary Behavior, Blood Pressure, Decision Support Systems, Clinical, Pre-Eclampsia, Plasminogen, Lipids, Cardiovascular Diseases, Coronary Vessels, Quality of Life, Estrogen Replacement Therapy, Estrogens, Atherosclerosis, Coronary Disease, Stroke, Risk Assessment, Myocardial Revascularization, Hysterectomy, Myocardial Infarction, Obesity, Triglycerides, Pulmonary Embolism, Uterus, Renal Insufficiency, Chronic, Neoplasms, Arthritis, Rheumatoid, Hypertension, Cholesterol, Mammography, Cohort Studies

< Back to Listings