Key Takeaways Comparing Lipid Guidelines Across the Pond: The Hot Off the Press 2019 ESC vs. 2018 ACC/AHA Guidelines

INTRODUCTION

The 2019 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guideline for the Management of Dyslipidaemias (ESC Guideline) was a highlight of the recent ESC meeting held in Paris, France.1 A key question for clinicians around the globe is 'How do these guidelines compare with the 2018 ACC/AHA Multisociety Guidelines for the Management of Blood Cholesterol (ACC/AHA Guideline)?'.2

COMMON GROUND

Published nine months after the 2018 ACC/AHA Guideline, the 2019 ESC and the ACC/AHA Guideline both seek to maximize the use of statin therapy and match intensity of treatment to risk level. This comes as no surprise as the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaboration analyses show that each decrease in low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) of 40 mg/dL (1.0 mmol/L) leads to a ~22% relative risk reduction in major vascular events.3

As expected, both guidelines identify LDL-C as a primary target of therapy given the immense evidence base. The common message between the guidelines resonates: that lower LDL-C is better with proven pharmacotherapy and better lifestyle habits. The guidelines are similar in emphasizing a 50% or more lowering of LDL-C and also identifying specific values of LDL-C to trigger further clinical action. If LDL-C remains suboptimal despite the maximum tolerated dose of a statin and lifestyle, then both guidelines agree on the concept that non-statin therapy can be considered in "very high-risk" adults.

Central to each set of guidelines in addressing the primary prevention population is the estimation of cardiovascular risk through accepted risk scoring systems, either the European SCORE (Systematic COronary Risk Evaluation) or the ACC/AHA Arteriosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) Risk Estimator and a comprehensive risk discussion with a clinician using shared decision making. Each set of guidelines makes specific recommendations for those considered at increased risk based on risk factors, risk modifiers, or risk enhancers. Both guidelines also give consideration to short-term, moderate-term and lifetime risk.

UNCOMMON GROUND

Definition of "Very High-Risk" Patient Population

Central to differences between these two guidelines is the definition of populations considered to be "very high-risk" and the management thereof, with a new absolute LDL-C goal of <55 mg/dL recommended in the ESC Guideline.

In the ACC/AHA Guideline, those at "very high-risk" of an ASCVD event only include true "secondary prevention" patients. This very high-risk category in the US guidelines includes patients with two major ASCVD events (defined by recent acute coronary syndrome (ACS), history of myocardial infarction (MI), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease (PAD), or at least one major ASCVD event plus two or more high-risk conditions).

In contrast, the ESC Guideline has broadened those at "very high-risk" to include anyone with documented ASCVD, either clinically or on imaging. This group would include all of those identified in the ACC/AHA Guideline, but additionally patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and end organ damage, severe chronic kidney disease (CKD) (eGFR <30ml/min/1.73m2) even in the absence of ASCVD, Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH) with ASCVD or with another other major risk factor, or a calculated heart SCORE of 10% (roughly equivalent to a 30% risk of 10-year ASCVD event in the pooled cohort equation).

This is surprising as creating one category for all of these patients appears to be an over-simplification. It is unclear, for example, what the evidence is to support the use of aggressive lipid lowering in patients with an eGFR of <30ml/min/1.73m2. More broadly, the population impact and cost implications of such widespread inclusion criteria are uncertain.

Risk Modifiers

New to the 2018 ACC/AHA Guideline was the consideration of multiple high-risk conditions (known as risk enhancing factors), defined as age >65 years, family history of premature ASCVD (males <55 years; females <65 years), inflammatory conditions (human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis), pregnancy associated conditions (premature menopause, pre-eclampsia), high-risk ethnicities (South Asian), and biomarker profiles associated with very high-risk (persistently elevated LDL-C, primary hypertriglyceridemia, hs-CRP ≥2.0 mg/L, elevated lipoprotein(a), or elevated apoB ≥130 mg/dL).2

The ESC Guideline also includes other factors that can significantly modify risk estimation including social deprivation, obesity and central obesity, physical inactivity, psychosocial stress, family history, chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disorders, major psychiatric disorders, treatment for HIV, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy, CKD, obstructive sleep apnea, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

We agree that these are important to include to more comprehensively determine risk. However, how these factors should be ideally used in combination and weighed relative to each other will need further clarification. Furthermore, the ESC Guideline does not mention sex-specific reproductive factors in the ACC/AHA Guideline (such as gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, preterm labor, age at menopause etc.), which have clearly been shown to modify ASCVD risk.

Management of "Very High-Risk" Patients

The ACC/AHA Guideline recommends that among patients with clinical ASCVD who are at very high-risk with LDL-C >70 mg/dL, it is reasonable to add ezetimibe after maximizing statin therapy. The initial goal with statin therapy is a ≥50% LDL-C reduction from baseline. The ESC Guideline advocates targeting an LDL-C <55 mg/dL and a ≥50% LDL-C reduction in very high-risk category patients.

For patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) at very-high-risk, an LDL-C reduction of at least ≥50% from baseline and LDL-C goal of <1.4 mmol/L (<55 mg/dL) is recommended in the ESC Guideline. In contrast, the ACC/AHA Guideline recommends treatment with moderate-intensity statin in patients with diabetes unless they have multiple diabetes specific risk enhancers, in which case, clinicians can consider the use of high intensity statin therapy with a goal of LDL-C reduction of at least ≥50% from baseline.

ACC/AHA "THRESHOLDS"

The ACC/AHA Guideline uses a threshold of 70 mg/dL before considering the addition of a non-statin in very high-risk patients. The concept of a threshold respects the importance of shared decision making between the patient and his/her clinician about adding additional therapy. The threshold is derived directly from the clinical trials, in particular the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES (Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes After an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment with Alirocumab) and FOURIER (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk) trials that enrolled patients with baseline LDL-C ≥70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C ≥100 mg/dL.

The ACC/AHA Guideline recommends that ezetimibe should be considered first since it is a generic medication and can be given orally. Furthermore, the PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies do not have long-term safety data, their cost is often quite high, and insurance coverage is variable. The ACC/AHA Guideline also attempts to direct therapy to patients who are most likely to benefit based on evidence that those with higher TIMI Risk Scores or other risk indicators benefit most.4,5

EUROPEAN "TARGETS" OR "GOALS"

The ESC Guideline takes a more aggressive approach with respect to PSCK9 inhibitors in patients with documented ASCVD, even without a recent ASCVD event. They have recommended that all patients achieve ≥50% reduction in baseline values and an absolute value of <55 mg/dL. While this is lower than the 70 mg/dL cut point identified in the ACC/AHA Guideline, the reality is that the typical very high-risk patient who is started on a PCSK9 inhibitor per the ACC/AHA Guideline will get well below the ESC Guideline goal of <55 mg/dL. The typical PCSK9 trial patient in the FOURIER trial started with LDL-C ~90 mg/dL and got down to 30 mg/dL.

The functional difference introduced by the ESC Guideline goal is largely therapeutic intensification in patients with LDL-C between 55 and 70 mg/dL. It is unclear how large of a population of patients this would impact, but it would likely markedly increase the number of patients eligible for PCSK9 inhibitors who were otherwise already close to their target on maximally statin plus ezetimibe. It is unknown if patients with clinically stable ASCVD without any other major ASCVD events or high-risk characteristics would derive clinically significant benefit from such an approach.6

EVIDENCE CITED BY ESC

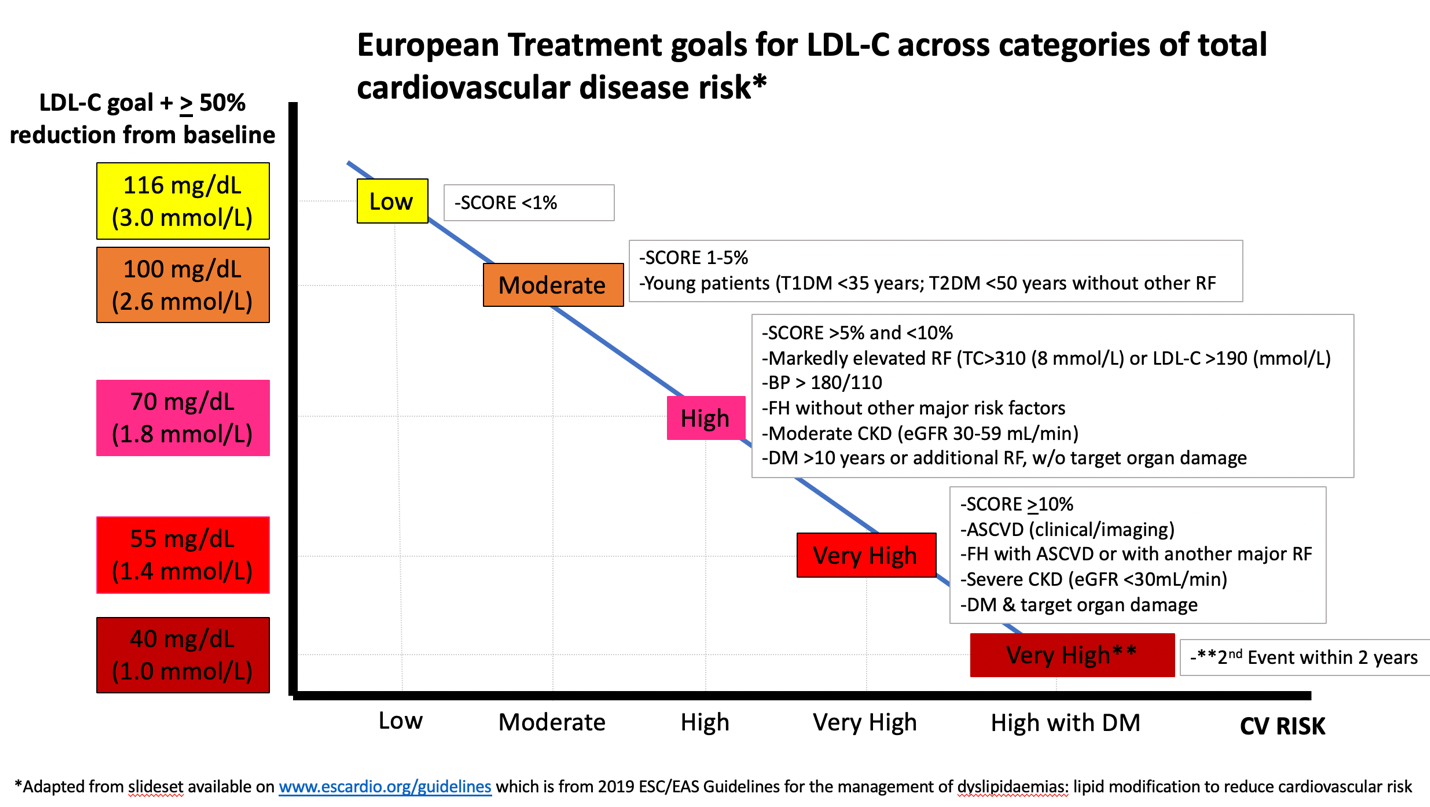

The authors of the 2019 ESC Guideline cite evidence from CTT,3 IMPROVE-IT (IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial),4 FOURIER,5 and ODYSSEY-OUTCOMES,7 to support the LDL-C goal of <55 mg/dL and additionally cite FOURIER and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES to justify a IIb recommendation for a goal of <40 mg/dL (<1.0 mmol/L) in patients, who experience a second vascular event within 2 years, while taking maximally tolerated statin therapy. Figure 1 from the presentation at the European Society of Cardiology Congress displays the relationship between their LDL-C goals and risk categories.

Figure 1

This approach is certainly an extrapolation of direct trial evidence. FOURIER included patients that had clinical ASCVD defined as history of MI, CVA, PAD, and ODYSSEY and IMPROVE-IT included patients with recent history of ACS. Not included were patients merely with imaging findings of asymptomatic ASCVD without a prior ASCVD event. With respect to LDL-C assessment, rather than upgrading to modern LDL-C estimation, the ESC Guideline still relies on the Friedewald equation. Since this underestimates LDL-C at lower levels in patients with elevated triglycerides, the <55 and <40 mg/dL goals may often be met, when in reality LDL-C is higher. Furthermore, the European recommendations do not comment on the overall cost benefit ratio whereas this was carefully considered in the ACC/AHA Guideline.

CONCLUSION

IMPROVE-IT, FOURIER, and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES form the backbone of recent evidence for intensifying LDL-C lowering therapy beyond statins. They enrolled patients with clinical ASCVD and prior events, not asymptomatic moderate atherosclerosis documented on angiography. Thus the conclusions of these trials cannot necessarily be extended to those patient populations with incidentally discovered ASCVD on imaging. The ACC/AHA Guideline adheres closely to the trial evidence whereas the ESC Guideline goes well beyond it.

Targeting an LDL-C reduction of ≥50% was similar between the guidelines, though the ACC/AHA Guideline has the concept of using an LDL-C threshold of ≥70 mg/dL to inform the addition of non-statin agents based on the trial entry criteria. In contrast, the ESC Guideline introduces an LDL-C goal of <55 mg/dL. One major question is whether there is sufficient incremental clinical benefit to further reducing a LDL-C from 60 mg/dL to <55 mg/dL, particularly in a group as broad as that identified in the new ESC Guideline. It remains unknown whether treating patients in primary prevention noted as very high-risk in the ESC Guideline (diabetes with end organ damage, severe CKD, calculated SCORE ≥10%) will derive sufficient incremental benefit from such aggressive LDL-C lowering including addition of ezetimibe and possibly PCSK9 inhibitors.

The ACC/AHA Guideline focuses on strictly-defined "very high-risk" patients to direct non-statin therapy to patients most likely to benefit, while the ESC Guideline approach includes patients with stable moderate coronary heart disease or primary prevention patients with moderate atherosclerosis on imaging (computed tomography (CT), angiography, or ultrasound). We are doubtful that clinicians in Europe liberally prescribe ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitor therapy to the extent advocated in the new guidelines or that this will be economically feasible. The cost-effectiveness of non-statin therapies in most of these primary prevention ESC Guideline "very high-risk categories" remains untested and unknown.

In summary, there are major conceptual similarities between the ACC/AHA and ESC guidelines and also major differences in how these concepts are operationalized. We believe that both guidelines are important and valuable resources to clinicians and patients. We intend this focused comparison of the two guidelines as a start to a conversation that will hopefully aid in understanding the guidelines better and implementing preventive therapies in practice. It is critical that differences in the guidelines do not lead to clinical inertia but rather curiosity to understand the underlying evidence better. The differences in the guidelines will need to be addressed through ongoing debate and evidence generation. Meanwhile, implementing either guideline will prevent many cardiovascular events.

References

- Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk: The Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS), Eur Heart J 2019;00:1-78.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018.

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010;376:1670–81.

- Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2387-97.

- Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1713-22.

- Bohula EA, Morrow DA, Giugliano RP, et al. Atherothrombotic risk stratification and ezetimibe for secondary prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:911–21.

- Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2097-2107.

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Cardiovascular Care Team, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Prevention, Vascular Medicine, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), Hypertriglyceridemia, Lipid Metabolism, Nonstatins, Novel Agents, Statins, Interventions and ACS, Interventions and Imaging, Interventions and Vascular Medicine, Angiography, Nuclear Imaging

Keywords: Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors, Acute Coronary Syndrome, Coronary Angiography, Cost-Benefit Analysis, Exploratory Behavior, Antibodies, Monoclonal, Risk Factors, Atherosclerosis, Primary Prevention, Diabetes Mellitus, Diabetes Mellitus, Coronary Disease, Outcome Assessment, Health Care, Decision Making, Insurance Coverage, Triglycerides, Renal Insufficiency, Chronic, Goals, Dyslipidemias, ESC Congress, ESC 19, Cholesterol, LDL, Risk Factors, Secondary Prevention, Peripheral Arterial Disease, Cardiovascular Diseases, Maximum Tolerated Dose, Myocardial Infarction, Stroke, Life Style, Diabetes Mellitus, Hypophosphatemia, Familial

< Back to Listings