Guest Editorial | COVID in the U.S.: A Clear Dichotomy

Christine M. Albert, MD, MPH, FACC, and Joanna Chikwe, MD, FACC

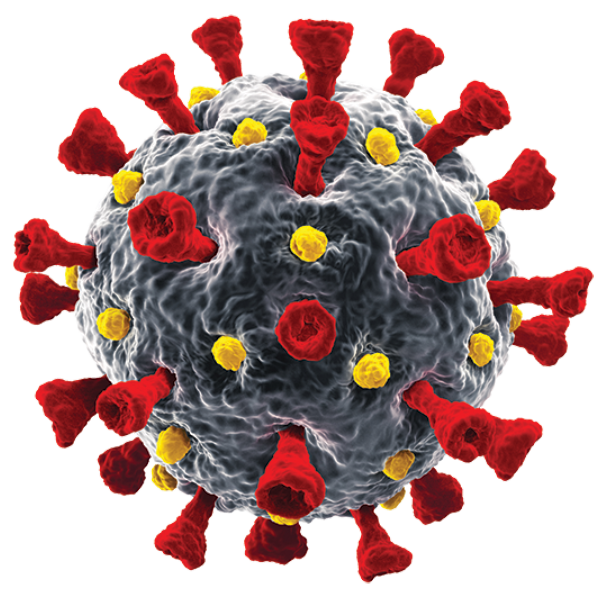

The experience of COVID-19 in the U.S. is a tale of two countries. National headlines have focused on health care systems overwhelmed by patients, exponential spread and high mortality in cities such as New York and New Orleans and in states like Michigan. But this has not been the experience of much of the U.S. Take California, which at 40 million has a population double that of New York state's 19 million.

Although it now appears that SARS-CoV-2 was circulating in the San Francisco Bay area for several weeks before the first cases were recognized in New York State, the impact of the disease has been vastly different. This is largely because early and effective social distancing slowed growth to a tiny fraction of the cases and deaths observed in New York.

Fortunately, despite extensive surge preparations, far fewer COVID-19 patients have needed hospital admission in California compared with New York. This may also partly explain why outcomes of hospitalized patients in California, where frontline staff and resources were never as overwhelmed as their New York counterparts, have been remarkably good.

However, this flattening of the COVID-19 curve has come at a terrible cost. Patients are now scared to go to their primary care doctors, their cardiologists' offices and the emergency room, where admissions are down by over 70% in many institutions.

Outpatient offices are also empty. Instead of the regular flow of patients for cardiovascular screening, elective assessment and intervention, we are seeing ventricular free wall rupture and ischemic ventricular septal defects often too late to salvage.

There is no way of knowing how many patients are dying at home of cardiac causes unrelated to COVID-19 because they have delayed seeking medical attention. One hint is that the mortality in most states last month was many times higher than normal, and only half of that was attributed to coronavirus.

While reducing nonessential medical care was a key part of the strategy for hospitals facing overwhelming demands on their critical care capacity, in the rest of the country where hospitals are sitting empty there is increasing concern that a quiet epidemic of cardiovascular mortality may exceed anything due to SARS-CoV-2.

The catheterization laboratory and operating rooms are quiet too. This is partly because that same normal flow of patients from primary care check-up to cardiology offices, testing and referral has completely ground to a halt.

It is partly because many states banned elective cardiac procedures for weeks to ensure there was sufficient critical care capacity for what was projected to be thousands of patients needing ventilators.

In states like California this never materialized, and the ban on elective care was lifted in early May. However, when we call patients to offer them a date for the cardiac surgery they still need, almost all of them – with the news headlines from New York, New Orleans and Michigan in mind – say, thank you but they prefer to wait a month or two longer.

Health care institutions and government are understandably extremely cautious about promoting a message that it is safe to see your health care provider and safe to go to the hospital for elective procedures.

The balance of risks for the truly elective cardiac patient is entirely different from the patient needing emergency surgery.

The risk associated with a hospital stay may not be the main issue, because the hospital has the ability to control exposure to SARS-CoV-2 through screening staff and patients, creating isolation areas, and changing how we interact with patients and each other.

Probably the greater challenge now is the risk of community spread of SARS-CoV-2 to patients after they have been discharged home. Again, lack of granular data on true disease prevalence and outcomes limits our ability to make informed decisions with our patients.

Much of this uncertainty will not be resolved soon. If we agree there is a significant and unacceptable increase in cardiac mortality, several things need to happen now to mitigate this particular curve, irrespective of the uncertainty.

First, regions like California where Sars-CoV-2 occupies a small fraction of critical care capacity, must start using the channels employed so effectively to keep patients at home to tell then it is safe to seek medical care, with a united message to the community from all care providers.

Second, we must support our community physicians: we need to recognize they are our best way of ensuring that patients who need hospital care receive it; perhaps even more importantly, they are key in reducing the need for hospital care through effective prevention and medical management.

We must ensure community physicians weather the financial and personal storms of this pandemic, with the resources they need to deliver patient care in this "new normal."

The emergency and critical care services have been the front line for COVID-19. Now primary care and cardiology offices are our best hope to prevent a surge in cardiac mortality.

Leading By Example

In September 2019, just days apart, Christine M. Albert, MD, MPH, FACC, and Joanna Chikwe, MD, FACC, were appointed as the founding chairs of the department of cardiology and department of cardiac surgery, respectively, at the Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles, CA – joining a growing cadre of female leaders in cardiovascular medicine.

Albert, who also became the new president of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) on May 8 during HRS 2020 Science, moved to Cedars-Sinai after more than 30 years in Boston, where she attended Harvard Medical School and completed her residency and fellowship training at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH).

She was on the faculty as a cardiac electrophysiologist at MGH and Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) and was the director of the Center for Arrhythmia Prevention at BWH and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

"I ran a large research program for many years at Harvard Medical School, I've been in the leadership track in my national society and I've been in the executive leadership in academic medicine," Albert says of her career path.

"All of this has helped prepare me to become chair of a department. Several sponsors have helped me throughout my career and given me advice. I still draw on them now."

While her focus is doing the best job she can for Cedars-Sinai, Albert acknowledges this is also a great opportunity for women to see another woman lead, providing encouragement for them.

Chikwe, whose focus is on coronary revascularization and mitral repair, arrived at Cedars-Sinai after 14 years at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. Originally from England, she graduated in medicine from Oxford University and completed her cardiac surgery residency training in the UK, before joining Mount Sinai Hospital in 2006.

"Cedars-Sinai has world-class experience in robotic mitral repair, thanks to over a decade of Dr. Alfredo Trento's pioneering leadership. It's been a real joy joining such an accomplished team and moving to the robotic platform," says Chikwe, describing the attractions of the new role.

"This approach to cardiac surgery is the best way to complement transcatheter therapies. Our mission is to match our preeminence in structural heart and transplantation across all domains of cardiac surgery. This includes being at the forefront of the clinical and translational research that will change practice."

Like Albert, Chikwe also sees an opportunity to encourage other women seeking leadership roles in the profession.

"It has become increasingly apparent to me there is a need for people to see leaders in the field who closely resemble their professional experience," she says.

"I hope by fulfilling my role as well as I can and also being very intentional about how I articulate the challenges and ways to address them I can help to complete the diversity of academic medicine at this institution."

Clinical Topics: Cardiac Surgery, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, COVID-19 Hub, Cardiac Surgery and CHD and Pediatrics, Congenital Heart Disease

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, COVID-19, Pandemics, Coronavirus, Internship and Residency, Patient Discharge, Length of Stay, Fellowships and Scholarships, Hospitals, General, Heart Septal Defects, Ventricular

< Back to Listings