Editor’s Corner | A Tale of Two Pandemics

At this point in the COVID-19 pandemic, with nearly 67 million cases and more than 1.5 million deaths globally, a look back at the influenza outbreak from 1918-1920 provides historical context as we deal with the global consequences of COVID-19.

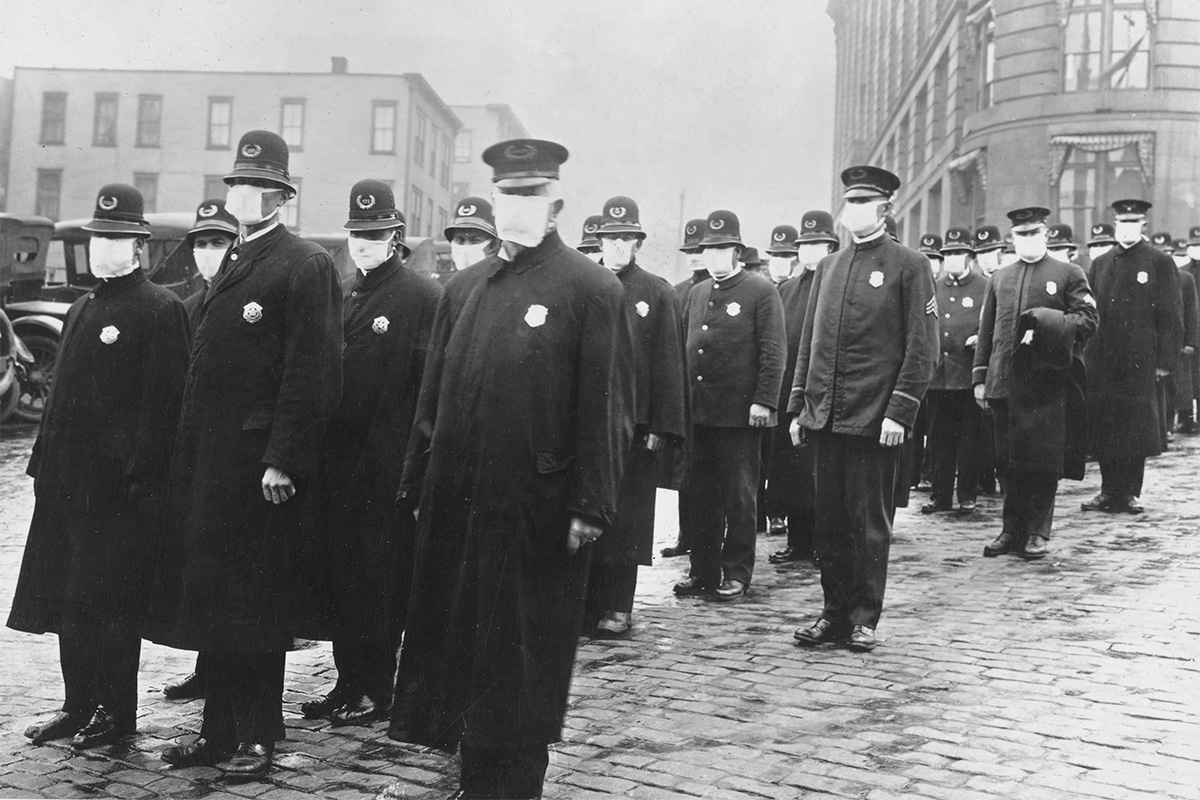

The 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic devastated populations around the world and is considered the deadliest infectious disease outbreak in modern history. There are striking similarities with the current pandemic: a startling range of symptoms from a contagion for which there was little treatment, and a public health response that incorporated behavioral changes that became a hindrance to implementing containment measures, including objections to wearing face masks and a focus on individual freedoms.

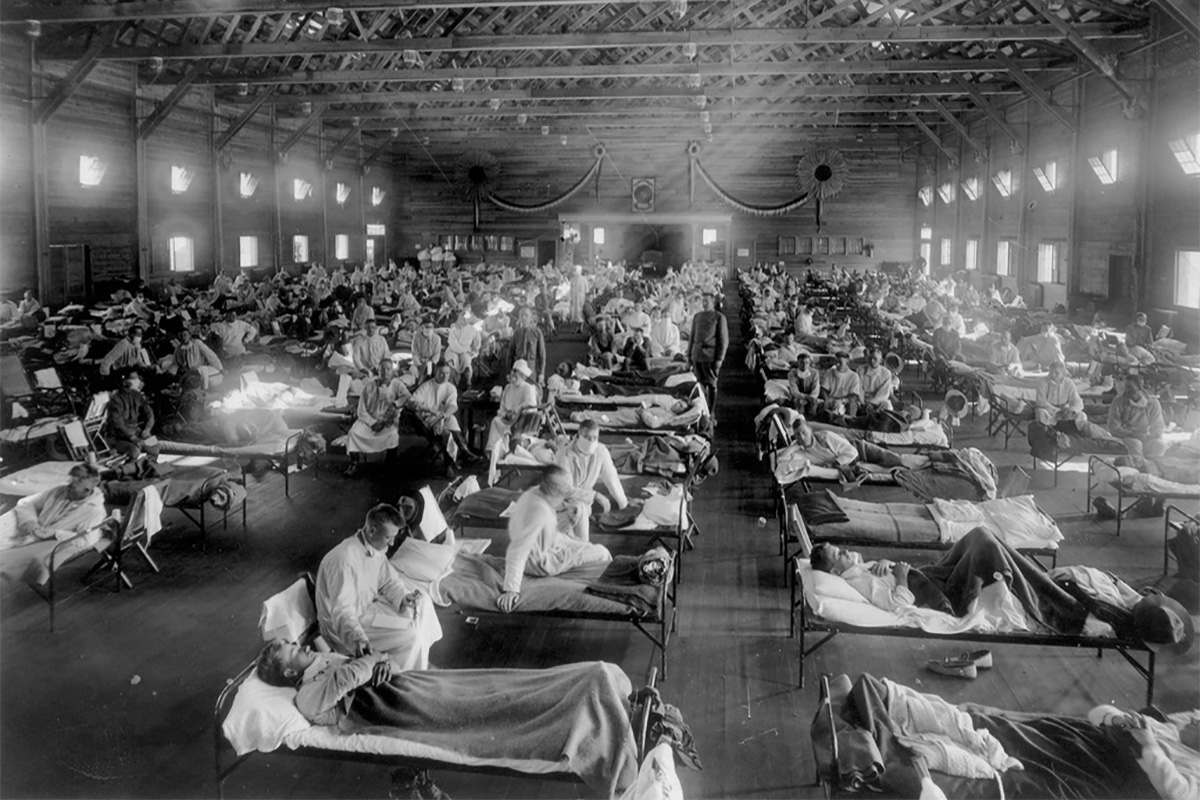

The first influenza cases were recorded at Fort Riley Army Base in Kansas in March 1918. By September, the flu epidemic reached Camp Devens in Massachusetts, and a fifth of the 50,000 soldiers were soon infected. Disease progression was rapid, from symptoms to pneumonia to death, at a median of eight to 10 days. Infected patients frequently died from suffocation within 24-48 hours of developing symptoms. The death toll exceeded 5%, with some army hospitals reporting up to 100 deaths a day. The 1918 influenza proved to be a far deadlier force than World War I.

Evidence suggests the virus initially spread slowly through the U.S. and it was carried by American troops to European battlefields, with the pattern of its spread directly related to troop movements.

The pandemic became known as the Spanish flu after articles about the influenza infection were written by the free press in Spain. This reporting was contrary to the Allied and Central Powers nations where wartime censors suppressed news of the flu to avoid affecting public morale.

No one really knows the true magnitude of the deaths from the 1918 flu pandemic. The outbreak impacted over one-third of the world's population. Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, the Australian virologist who received the 1960 Nobel Prize of Physiology or Medicine, concluded the worldwide death toll likely exceeded 50 million and may have approached 100 million.

John M. Barry, who wrote the book titled The Great Influenza noted that he "…wanted to explore how individuals who had at least some power to deal with this challenge reacted, whether they be politicians or scientists, and what effects their decisions had on society…"

World War I which had begun on July 28, 1914 and ended on Nov. 11, 1918 played a pivotal role in the pandemic. The political response to the pandemic by the administration of President Woodrow Wilson focused on patriotism rather than science, with intimidation and propaganda a part of the communication culture.

Wilson chose to ignore the impact of the pandemic and focus his efforts entirely on winning the war, leading to more illness and death.

The Sedition Act of 1918, made it a crime to "willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of the Government of the United States" or to "willfully urge, incite, or advocate any curtailment of the production" of the things "necessary or essential to the prosecution of the war."

The Act and the pressure to support the war effort further impacted the public health efforts to contain the pandemic. The political perception was that the disease was so widespread that there would be no benefit from public action.

The dictum from the Wilson administration was to exclusively focus on the war effort and not to interfere with public morale. Ironically, Wilson would later become stricken with influenza in April 1919 during the Paris Peace Conference where he hoped to establish a League of Nations. Wilson was bedridden during critical parts of the treaty negotiations and likely experienced neurologic sequelae. COVID-19 has already infected several heads of state, including President Donald J. Trump and Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

In 1918, two different cities had two different views on public gatherings. And vastly different outcomes. Philadelphia hosted a Liberty Loan parade to promote the sale of war bonds, just 11 days after the report of the first influenza case in the city and launch of a public health campaign.

The gathering of 200,000 people for the parade contributed to widespread outbreak, and within 72 hours all 31 of the city's hospitals were at capacity; 22,000 cases were reported over a two-week span and 2,600 deaths were recorded within one week. In Missouri, St. Louis "flattened the curve" and limited the spread of the flu by canceling its war bonds parade.

With no vaccines or antibiotics to treat complications of the 1918 pandemic, health care professionals focused on classic public health measures including quarantining, social distancing, mask wearing, hand washing, sanitizing surfaces, fresh air and adaptive schooling.

Active immunization began with smallpox and was popularized by Edward Jenner in his 1798 paper. Modern vaccine production dates to the polio epidemic and the first polio vaccine in 1954.

The importance of public trust is a key lesson from the previous flu pandemic. Fear and lack of transparency led to social breakdown. Maintaining trust and transparency in reporting and leaders following the advice from scientists should help to facilitate compliance with public health recommendations such as social distancing and wearing masks.

A poorly mitigated pandemic can overwhelm medical resources and over-extended networks create the risk of cascading failures. Nonpharmaceutical interventions to control COVID-19 including social distancing and masks have been shown to be effective in various parts of the world with inconsistent implementation in the U.S.

COVID-19 is likely to be with us for some time despite the introduction of effective vaccines. The public health lessons of 1918 are relevant 102 years later as we look forward to our "nostalgic future" when we can look back on the current pandemic as a lesson of history and the constant reminder that we are subject to the whims of nature when it comes to infectious diseases.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, COVID-19 Hub

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, History, 20th Century, Smallpox, Sanguisorba, COVID-19, Influenza A Virus, H1N1 Subtype, World War I, Influenza, Human, Negotiating, Public Health, Military Personnel, Hand Disinfection, Propaganda, Hospitals, Military

< Back to Listings