Palliative Care Consultation and the Transition to Hospice for Patients with End-Stage CVD

Quick Takes

- Hospice care is underutilized in HF patients despite its known benefits including improved family satisfaction and symptom management.

- Cardiologists have a crucial role in ensuring adequate preparation for hospice and optimal end-of-life care by addressing decisions about implanted devices and continuing medication management.

- Early primary and secondary palliative care can lead to improved advance care planning, symptom management, and increased timely transitions to hospice.

As a follow up to an expert analysis published April 2016, we present the below key points:

- A statistic to remember: Only 4% of Medicare patients with end-stage heart failure (HF) were transitioned to hospice at discharge.

- Unlike in cancer and dementia, the interplay between curative and palliative care for HF can be more complicated, illustrated by the fact that most elements of optimal HF therapy improve symptoms and confer survival benefit.

- Due in part to its course of frequent decompensations and improvements following hospitalization, prognostication in end-stage HF can be difficult.

- Potential barriers to hospice for patients with HF include difficulty in prognostication, inadequate preparation for hospice, and lack of comfort in cardiac management on the part of hospice agencies.

- Despite benefits of hospice including increased survival and higher family satisfaction, hospice utilization in HF patients remains very low.

- Cardiologists have a critical role in ensuring smooth transitions to hospice and optimal end-of-life care by addressing devices and continuing cardiac medication management.

- Defibrillators should be deactivated to avoid painful and anxiety-provoking shocks at the end of life. However, patients are often unaware that their device settings can be altered.

- Early palliative care consultation is recommended as part of guideline directed management for patients with HF. Palliative care consultants assist with defining patient values, wishes, and goals, leading to improvement in caregiver support, completion of advance care planning, and timely transition to hospice.

Palliative care provides symptom management, psychosocial support, and facilitation of shared decision-making and can be provided by any clinician, but in many cases, there is a need for specialist involvement. Patients with cardiovascular disease at end of life suffer a high burden of cardiac and non-cardiac symptoms and face complex medical decisions. In recognition of the needs of patients with HF, guidelines and scientific statements1,2 recommend palliative care involvement, especially for patients with stage D HF. The Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services have also mandated that palliative care specialists participate in the care of patients considered for destination ventricular assist device (VAD) therapy. Nonetheless, few patients with HF receive formal palliative care. In a chart review of 1,320 patients admitted for HF, only 10% received palliative care consults. The mean time from palliative care consultation to death was 21 days.3 Only 4% of Medicare patients with end-stage HF were transitioned to hospice at discharge.4

Challenges inherent in providing end-of-life care to the patient with HF include difficult prognostication and complexities in medical and device management.5 These aspects may serve as barriers to timely palliative care and prevent appropriate transfer to hospice, despite the life-limiting and highly symptomatic nature of end-stage cardiac disease.6 Difficulty in prognostication for patients with HF has been well known since the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments SUPPORT trials over 25 years ago.7,8 Despite the development of models that are accurate for populations, prognostication for individuals remains problematic.9 The unpredictable trajectory of HF complicates the ability to identify patients at end of life.5

Unlike cancer and dementia in which the distinction between curative and palliative treatment is often clear, cardiac medications and devices usually provide the dual effect of symptom alleviation and life prolongation. Patients with HF may be offered or have previously received an array of implanted device therapies including a host of medications, defibrillation, pacing, resynchronization, and mechanical ventricular support to prevent sudden cardiac death and to improve symptoms and quality of life. As patients approach end of life, withdrawal, or modification of device therapies, in particular, is appropriate and should be directed by patients' goals and values. Shocks at the end of life are associated with pain, anxiety, poor quality of life, and even mortality.10 On the other hand, withdrawal of pacing and resynchronization may result in worsening of symptoms and quality of life.11 Depending on patients' goals and values, it may be reasonable to continue these functions even when defibrillation is deactivated. Patients with VADs may endure complications such as infection, bleeding, thrombotic events, and pump failure at any time after implantation.12 In addition, they face loss of decision-making capacity in the setting of a debilitating stroke.13 However, many patients with implanted devices have never considered how to address device deactivation at the end of their lives or discussed it with their clinicians.14 Many cardiologists lack comfort in addressing implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) deactivation in particular,15 despite scientific statements recommending that circumstances in which device therapy would not align with patients' goals should be discussed at the time of implant.16

In light of these barriers, palliative care specialist involvement should be considered early in the disease process, but especially as patients face difficult decisions related to shifting focus from curative therapy to palliation and hospice. Critical turning points in the course of a patient's illness often signal the need to address palliative care decisions and consider transition to hospice, including changes in symptoms, need for additional interventions, complications of therapies, and development of other life-limiting diseases such as dementia and cancer.17 Palliative care consultants assist with identifying these points and defining patient values, wishes, and goals, establishing the foundation for shared decision-making about foregoing and/or limiting interventions, and transitioning to hospice.18 Cardiologists and palliative care specialists should decide jointly if the patient is optimally treated and prudently consider candidacy for percutaneous interventions such as Mitra Clip™. In addition to increased completion of advance care directives, timely referrals to hospice, palliative care consultation can also result in fewer readmissions and mechanical ventilation utilization.19,20

According to Medicare hospice guidelines, hospice may be considered for patients with HF if they are 1) optimally treated or not a candidate for surgery or other interventions and 2) New York Heart Association (NYHA) IV with symptoms at rest despite medical therapy, preferably with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). Other supporting factors include presence of symptomatic arrhythmias, refractory ventricular arrhythmias, history of cardiac arrest, history of syncope, or history of stroke due to cardiac embolism.21 Notably, one observational study found that patients with HF who were enrolled in hospice had a mean survival of 29 days longer than those not in hospice.22 Longer length of stay in hospice is also associated with improved symptom control and increased family satisfaction.23 Ongoing cardiology input is beneficial for optimal titration of cardiac medications and device therapy as hospice agencies may lack comfort in primary management.

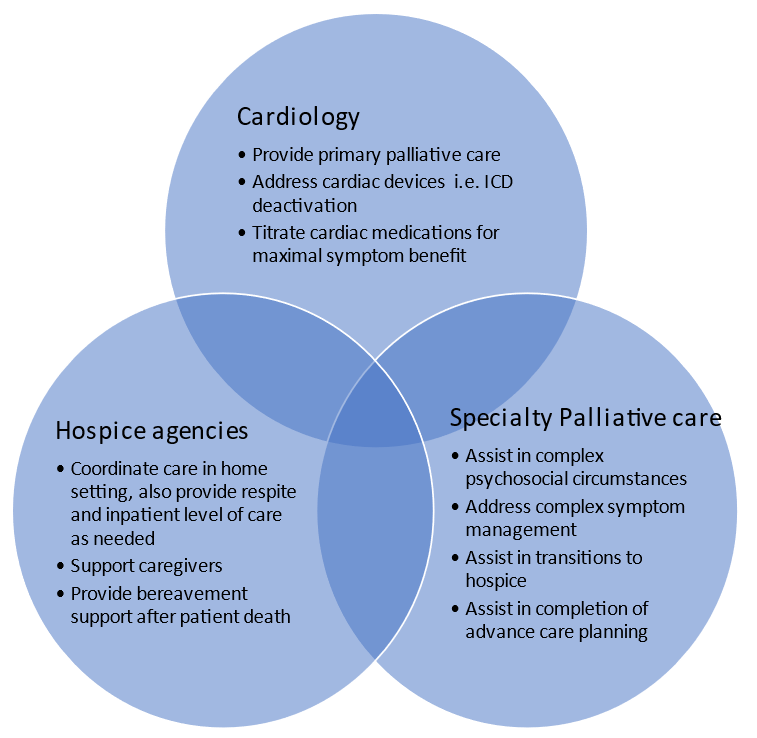

In sum, given the complex prognostication and nuances in management of cardiac medications and devices, early and iterative collaboration between primary care clinicians, cardiologists, palliative care specialists, and other specialists ensures comprehensive end-of-life care for patients with HF, particularly aiding appropriate transition to hospice (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Optimal End of Life Care

References

- Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic HF in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46;e-1-82.

- Fang JC, Ewald GA, Allen LA, et al. Advanced (stage D) heart failure: a statement from the Heart Failure Society of America Guidelines Committee. J Cardiac Fail 2015;21:519-34.

- Bakitas M, Macmartin M, Trzepkowski K, et al. Palliative care consultations for heart failure patients: how many, when, and why? J Card Fail 2013;19:193-201.

- Warraich HJ, Xu H, DeVore AD, et al. Trends in hospice discharge and relative outcomes among Medicare patients in the Get with The Guidelines–Heart Failure Registry. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:917-26.

- Goodlin SJ. Palliative care in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:386-96.

- Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Long-term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1435-43.

- Connors AF, Dawson NV, Desbiens NA, et al. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA 1995;274:1591-98.

- Krumholz HM, Chen J, Murillo JE, Cohen DJ, Radford MJ. Admission to hospitals with on-site cardiac catheterization facilities: impact on long-term costs and outcomes. Circulation 1998;98:2010-16.

- Lewis EF. End of life care in advanced heart failure. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2011;13:79-89.

- Sobanski P, Jaarsma T, Krajnik M. End-of-life matters in chronic heart failure patients. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2014;8:364-70.

- Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, et al. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1539-49.

- Mueller PS, Jenkins SM, Bramstedt A, Hayes DL. Deactivating implanted cardiac devices in terminally patients: practices and attitudes. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2008;31:560-68.

- Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, et al. Sixth INTERMACS annual report: a 10,000-patient database. J Heart Lung Transplant 2014;33:555-64.

- Swetz KM, Kamal AH, Matlock DD, et al. Preparedness planning before mechanical circulatory support: a 'how-to' guide for palliative medicine clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:926-35.

- Kirkpatrick JN, Gottlieb M, Sehgal P, Patel R, Verdino RJ. Deactivation of implantable cardioverter defibrillators in terminal illness and end of life care. Am J Cardiol 2012;109:91-94.

- Lampert R, Hayes DL, Annas GJ, et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the management of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) in patients nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of therapy. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:1008-26.

- Goodlin SJ, Hauptman PJ, Arnold R, et al. Consensus statement: palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. J Card Fail 2004;10:200-09.

- Allen LA, Smoyer Tomic KE, Smith DM, Wilson KL, Agodoa I. Rates and predictors of 30-day readmission among commercially insured and Medicaid-enrolled patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:672-79.

- Diop MS, Bowen GS, Jiang L, et al. Palliative care consultation reduces heart failure transitions: a matched analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e013989.

- Goodlin SJ, Kutner JS, Connor SR, Ryndes T, Houser J, Hauptman PJ. Hospice care for heart failure patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;29:525-28.

- Original Medicare (Part A and B) Eligibility and Enrollment (CMS.gov). 2021. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Eligibility-andEnrollment/OrigMedicarePartABEligEnrol/. Accessed 11/15/2021.

- Connor SR, Pyenson B, Fitch K, Spence C, Iwasaki K. Comparing hospice and nonhospice patient survival among patients who die within a three-year window. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:238-46.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Care Team, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Acute Heart Failure, Mechanical Circulatory Support, Sleep Apnea, Geriatric Cardiology

Keywords: Palliative Care, Quality of Life, Angiotensin Receptor Antagonists, Hospices, Patient Discharge, Length of Stay, Cardiovascular Diseases, Caregivers, Consultants, Follow-Up Studies, Goals, Heart-Assist Devices, Medicaid, Medication Therapy Management, Patient Readmission, Personal Satisfaction, Psychosocial Support Systems, Respiration, Artificial, Medicare, Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors, Terminal Care, Advance Care Planning, Neoplasms, Heart Failure, Referral and Consultation, Life Support Care, Heart Diseases, Heart Arrest, Defibrillators, Angiotensins, Arrhythmias, Cardiac, Dementia, Syncope, Embolism, Anxiety, Stroke, Pain

< Back to Listings