Cardiac Rehabilitation and Health Care Disparities in the Post-COVID-19 Era

Quick Takes

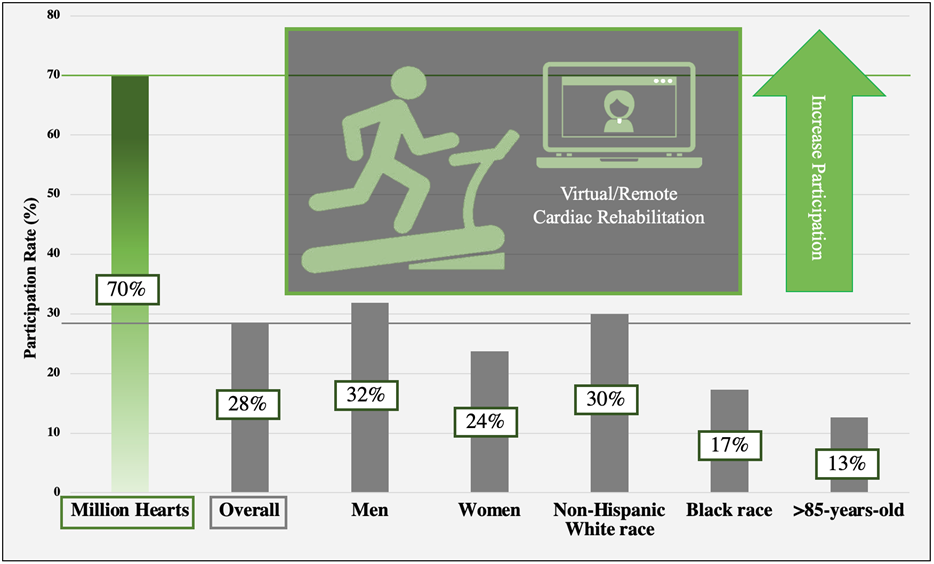

- Overall utilization of cardiac rehabilitation (CR) remains low, at 28% of eligible patients.

- Women, Black patients, patients >85 years of age, and those living in a rural setting have emerged as having particularly low utilization.

- Virtual CR may represent an opportunity to narrow the gap in utilization between these groups, but few contemporary studies have targeted these populations.

Despite robust evidence and consensus recommendations for cardiac rehabilitation (CR), United States (US) uptake remains low, reaching only 28.6% of eligible Medicare beneficiaries,1 with lower participation rates in women, patients ≥65 years of age, Black patients, and patients living in rural settings.2 The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused a further 94% decline in participation that remains lower than prepandemic rates.3 In response, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded telehealth reimbursement to include virtual cardiac rehabilitation (VCR) in 2020. Since then, national use of telehealth services has rapidly expanded from 0.5% to now 5% of all claims.4 Accordingly, the COVID-19 pandemic prompted introduction of several nontraditional care-delivery models for CR that hold promise for addressing the aforementioned disparities.

New Care-Delivery Models

CR is a multidisciplinary, exercise-based intervention for patients with established coronary artery disease, heart failure, or peripheral arterial disease, and for patients following cardiac surgery.2 The American Heart Association (AHA), American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR), and CMS have published criteria for certification and coverage that standardize this complex intervention. Telehealth coverage expansions during the pandemic led to three CR care-delivery models: facility-based cardiac rehabilitation (FBCR), hybrid cardiac rehabilitation (HYCR), and remote cardiac rehabilitation (RCR).5,6 FBCR alone involves real-time, in-person, supervised exercise. HYCR offers a mix of FBCR and VCR, which entails exercise at any location with synchronous video conferencing during exercise. RCR allows independent exercise at any location with occasional asynchronous video counseling. Although CMS coverage of VCR will end in 2023, the Sustainable Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation Services in the Home Act is currently in the US House of Representatives and may extend coverage indefinitely.

CR in Low-Utilization Populations

CR utilization can be understood academically and clinically in terms of referral, enrollment, and completion. Referral occurs when a clinician orders CR, enrollment (or participation) indicates that a patient attended at least one CR session, and completion indicates that the session series was finished. These components are also important in a regulatory sense, as the Joint Commission acknowledges both appropriate CR referral and enrollment in its Comprehensive Cardiac Center (CCC) certification.

Women

Women participate in CR 26% less often than men (31.9% vs. 23.7%).1 Referral rates for women are approximately 10-32% lower than for men, with little improvement over time. Even after adjusting for age and comorbid conditions, enrollment rates are approximately 10% lower for women than for men. Lack of transportation, lack of enjoyment, and home responsibilities are cited more frequently by women as reasons for nonparticipation.7,8 This area is under-researched, with only six trials specifically targeting women in a 2019 meta-analysis of 26 trials (n = 297,719). Most patients in these trials were male (66-87%).9 A 2022 systematic review found 28 separate studies of women-focused CR. Interventions to tailor FBCR to women generally focus on female-only sessions and tailoring education to the needs of women. Only five studies included in this review focused on remote interventions, but adherence was not reported in those studies.10

Black Patients

Black patients are referred 20% less frequently than are non-Hispanic white patients.8 Enrollment is also low, as Black patients participate in CR half as often as white patients (17.3% vs. 30%).1 One study of 107,199 patients (12% Black) with an indication for CR found that Black patients participate in CR 18% less often than do white patients, with no impact from controlling for median household income.11 Completion rates were comparable between Black and white patients in a large cohort of 412,080 Medicare beneficiaries (~60% of those with at least one session attended).1 Virtual interventions may attract minority patients. In one contemporary cohort of 2,500 Kaiser Permanente patients, a smaller proportion of Black patients enrolled in FBCR than in home-based CR (6.8% vs. 8.3%).12

Rural Setting

Rural patients face enrollment challenges because of limited access. An AHA presidential advisory recently named poor rural access to phase II CR as a contributing factor to poor cardiovascular (CV) outcomes.13 Those living >15 mi (24.1 km) from a CR center are 71% less likely to be enrolled than are those who live <1.5 mi (2.4 km) away.8 A recent analysis of >1 million patients eligible for CR found that 21.2% of the geographic variation in CR enrollment was due to CR density within the hospital referral region.14 Conversely, in a similar Medicare analysis from 2017 to 2018, eligible patients participated in and completed CR more often in rural counties than in urban counties despite low CR density.15 Additionally, virtual models might be problematic in rural areas because of limited broadband internet access (24% of households do not have broadband internet in urban settings vs. 32% of households in rural settings).16

Patients 65 Years of Age or Older

There is a gradual drop in participation in CR as patients age, dropping to one-third of baseline values in those >85 years of age.1 A survey of patients who participated in the SILVER-AMI (Comprehensive Evaluation of Risk Factors in Older Patients with AMI) study, a post-acute coronary syndrome cohort of patients >75 years of age enrolled in CR, uncovered a participation rate of 39%. Older age and functional and sensory impairments common in aging led to lower rates of participation.17 Virtual, home-based interventions suggest benefit. A European population of patients eligible for CR and >65 years of age across five countries evaluated participation and effectiveness of RCR in those who declined participation in traditional FBCR. Overall, 26% of screened patients enrolled, and their exercise capacity was improved compared with that of control patients (who received no CR).18

Figure 1 shows some of the differences in enrollment in CR across these low-utilization populations compared with overall enrollment and the goal set by the Million Hearts Collaboration (American Heart Association, Dallas, Texas).

Figure 1

Conclusions and Future Directions

Mounting evidence supports that race, geography, sex, and age influence CR utilization, a life-prolonging, morbidity-reducing intervention for CV disease. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), through their TAKEheart initiative to improve CR utilization, has released a guide for programs interested in implementing HYCR programs, one that includes an optional VCR component in addition to FBCR.19 Large studies introducing under-referred populations, such as those described earlier, to virtual care-delivery models to focus on improving participation are needed to push utilization closer to the Millions Hearts Collaboration's goal of 70% (Figure 1). Future studies should adhere methodologically to: 1) consensus nomenclature such as that proposed by the Million Hearts Collaboration; and 2) clear and comprehensive descriptions of interventions included in the care-delivery platform to meet the US national standard set by the AACVPR.

References

- Keteyian SJ, Jackson SL, Chang A, et al. Tracking cardiac rehabilitation utilization in Medicare beneficiaries: 2017 update. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2022;42:235-45.

- Beatty AL, Beckie TM, Dodson J, et al. A new era in cardiac rehabilitation delivery: research gaps, questions, strategies, and priorities. Circulation 2023;147:254-66.

- Varghese MS, Song Y, Xu J, et al. Availability and use of in-person and virtual cardiac rehabilitation among US Medicare beneficiaries: a post-pandemic update. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2023;43:301-3.

- Shaver J. The state of telehealth before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Prim Care 2022;49:517-30.

- Beatty AL, Brown TM, Corbett M, et al. Million Hearts Cardiac Rehabilitation Think Tank: Accelerating New Care Models. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2021;Oct:[ePub ahead of print].

- Golbus JR, Lopez-Jimenez F, Barac A, et al.; Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Secondary Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young, Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Digital technologies in cardiac rehabilitation: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;148:95-107.

- Smith JR, Thomas RJ, Bonikowske AR, Hammer SM, Olson TP. Sex differences in cardiac rehabilitation outcomes. Circ Res 2022;130:552-65.

- Mathews L, Brewer LC. A review of disparities in cardiac rehabilitation: evidence, drivers, and solutions. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2021;41:375-82.

- Pio CSA, Chaves G, Davies P, Taylor R, Grace S. Interventions to promote patient utilization of cardiac rehabilitation: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2019;8:189.

- Mamataz T, Ghisi GLM, Pakosh M, Grace SL. Nature, availability, and utilization of women-focused cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2021;21:459.

- Garfein J, Guhl EN, Swabe G, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in cardiac rehabilitation participation: effect modification by household income. J Am Heart Assoc 2022;Jul 5:[ePub ahead of print].

- Nkonde-Price C, Reynolds K, Najem M, et al. Comparison of home-based vs center-based cardiac rehabilitation in hospitalization, medication adherence, and risk factor control among patients with cardiovascular disease. JAMA Netw Open 2022;Aug 1:[ePub ahead of print].

- Harrington RA, Califf RM, Balamurugan A, et al. Call to action: rural health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association. Circulation 2020;141:e615-e644.

- Duncan MS, Robbins NN, Wernke SA, et al. Geographic variation in access to cardiac rehabilitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;81:1049-60.

- Van Iterson EH, Laffin LJ, Bruemmer D, Cho L. Geographical and urban-rural disparities in cardiac rehabilitation eligibility and center-based use in the US. JAMA Cardiol 2023;8:98-100.

- Van Iterson EH, Laffin LJ, Cho L. National, regional, and urban-rural patterns in fixed-terrestrial broadband internet access and cardiac rehabilitation utilization in the United States. Am J Prev Cardiol 2022;Dec 24:[ePub ahead of print].

- Goldstein DW, Hajduk AM, Song X, et al. Factors associated with cardiac rehabilitation participation in older adults after myocardial infarction: the SILVER-AMI study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2022;42:109-14.

- Snoek JA, Prescott EI, van der Velde AE, et al. Effectiveness of home-based mobile guided cardiac rehabilitation as alternative strategy for nonparticipation in clinic-based cardiac rehabilitation among elderly patients in Europe: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2021;6:463-8.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Hybrid Cardiac Rehabilitation (HYCR) Expanding Capacity Implementation Guide (AHRQ website). 2022. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/takeheart/training/expanding-cardiac-rehab-capacity/index.html. Accessed 09/11/2023.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, COVID-19 Hub, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Prevention, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, Vascular Medicine, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), Acute Heart Failure

Keywords: Primary Prevention, COVID-19, Sports, Coronary Artery Disease, Heart Failure, Telerehabilitation, Peripheral Arterial Disease, Cardiac Rehabilitation, Healthcare Disparities

< Back to Listings