My Transition to Practice as a WIC During the COVID-19 Pandemic

To say that these have been strange times would be an understatement. COVID-19 has been a reckoning in many ways – of the status quo, of our global interdependence and of how we see our futures. This pandemic has certainly taught me invaluable lessons in my own career.

COVID-19 caught me at the transition point between fellowship and practice. After the completion of my clinical cardiology training by way of an advanced echocardiography and research fellowship at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, MA during 2019, I decided to pursue the Cardiovascular Disease and Global Health Equity fellowship through the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School (HMS). Health care delivery for the most vulnerable has always been a driving force for me throughout medical training. This fellowship was a perfect fit for my desire to link my cardiology and echocardiography training with my convictions about health equity for the poorest in the world, many of whom live on the African continent.

I heard the news about COVID-19 in February while traveling from Rwanda back home to Boston. Probably like many of you, I listened to the news with the air of someone far removed from the initial outbreaks. At least until it hit Washington state. Even then, it did not bother me to travel to Alberta, Canada, where I did intermittent locum work throughout fellowship. About one week into this locum (mid-March), as COVID-19 case counts ratcheted out of control globally, I realized I did not feel safe traveling home to Boston. Several days after that, the Canada-U.S. border closed.

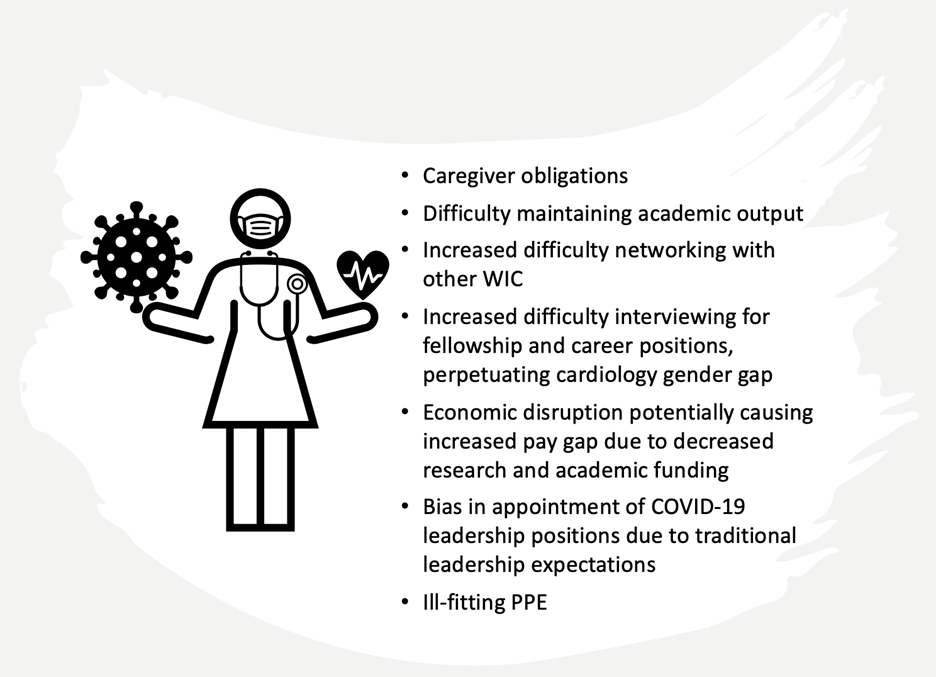

Figure 1: Barriers specific to women in cardiology during the COVID-19 pandemic

This leads to my first lesson learned of this pandemic: be flexible and pivot. Based on anecdotal experience, I suspect that many women in cardiology (WIC) are like me: organized planners, obsessively hardworking, a little bit neurotic. In a male-dominated field, I have always felt the need to be better than my peers, just to "keep up". Finding myself in temporary housing in Canada, with upcoming fellowship time in Liberia cancelled and the world in chaos was mentally and emotionally challenging, to put it mildly. It took me four weeks to come to terms with the fact that I would not be completing my global health fellowship (at least in the way I had planned) and I was not returning to my Boston apartment. Many of us will remember what March and April of 2020 felt like – when little was known about this new virus and countries across the globe were locking down for containment. At the same time, I felt a professional obligation to assist with the COVID-19 response locally, and I needed to turn this sudden gap at the end of fellowship into a career move. Over the course of the subsequent months, I signed a half-time clinical appointment with Alberta Health Services. My program director and I rolled my fellowship over into an HMS faculty position as our entire team transitioned to virtual work. The end of my training and my transition to practice happened in the most unconventional way. It felt quite underwhelming as most of my peers were too stressed, busy or distracted to take notice. With COVID-19 having been the most dramatic example, there have always been forces in my professional life that have demanded that I alter my path. No doubt you have encountered these as well. These are times when we must take that proverbial deep breath, look at our options, and be willing to take that 90-degree turn. The ability to pivot, to do so early, and to do so well is an asset but requires support and mentorship. More on that later.

The second lesson, for which I have gained enormous appreciation over this past year, is to be creative with opportunity. In my personal life, the end of medical training was an opportunity to finally own a home which again, during the period of pandemic lockdown was an awkward situation to navigate. However, we had a very resourceful real estate team and (taking the appropriate COVID precautions) we signed a charming small home at an excellent price. Travel bans and lockdowns meant that my friendships scattered across Canada and the U.S. became entirely virtual. Because none of us could not leave home, location could not have mattered less. We all found new ways of celebrating and connecting. This was the first time I had ever "Zoomed" into a friend’s wedding. In some cases, we deepened our relationships as we struggled through the period of isolation together. In my career, within the Program for Global Noncommunicable Diseases and Social Change at HMS, our team has been advocating for decentralization of care to rural settings for patients with complex chronic disease in low-income countries, which greatly improves access and decreases impoverishment. We spent this time of restricted international travel adapting our in-person training for health care providers into virtual learning material which will make our training richer and more easily scaled once we are able to rejoin our partners in Africa.

We are painfully aware that this pandemic has brought to light all the faults and disparities of our societies. The struggle of women cardiologists is no exception. The barriers facing WIC at baseline are clear enough: gender discrimination (1), greater family responsibilities (1), difficulty achieving career advancement (1), and a paucity of role models (2), among others. There are also barriers that have been specific to COVID-19 (Figure 1). In the exponentially heightened stress environment of the workplace, women may not only feel more scrutinized within the health care team but may have watched as leadership positions have fallen to men in this "high stakes situation."

This brings me to my last lesson, which is one that I cannot emphasize enough: make use of your supports and be sure to support others. During this challenging time, our strength is each other. My fellowship-to-career transition during the pandemic would not have been possible without colleagues, both women and men, who have put their shoulder behind my transition despite their own heightened stress and competing priorities. During this time, I am exceedingly grateful to my mentors, again both men and women, who have played an enormous role in my career trajectory. They have built in me the resilience and clinical skill needed to transition to independent practice, in relative isolation, during a pandemic. They continue to be readily available to discuss challenging cases and answer my questions with honesty and humor. They continually encourage me to aim high, but also remind me what is realistic. I would recommend to my fellow WIC, particularly those still in training or in early career, to seek out those mentors and surround yourself with those who support you.

In some ways, COVID-19 has been a litmus test for progress that WIC have made, but I have been encouraged during the pandemic by the way I have seen this community move forward. Several of my WIC colleagues, including myself, have been able to maintain academic and clinical productivity with the support of our spouses. Some WIC colleagues have assumed COVID-specific leadership positions. We early career WIC stand on the shoulders of exceptional women who have come before us, and must continue to pave the way for the women in training who will someday be in our position. Together, even in the face of a global pandemic, we can help each other pivot to meet change, be creative with opportunity and strive together for more gender equity.

References

1. Limacher M, Zaher C, Walsh M, Wolf W, Douglas P, Schwartz J, et al. The ACC professional life survey: career decisions of women and men in cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998 Sep;32(3):827–35.

2. Blumenthal DM, Olenski AR, Yeh RW, DeFaria Yeh D, Sarma A, Stefanescu Schmidt AC, et al. Sex Differences in Faculty Rank Among Academic Cardiologists in the United States. Circulation. 2017 Feb 7;135(6):506–17.

This content was developed independently from the content developed for ACC.org. This content was not reviewed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) for medical accuracy and the content is provided on an "as is" basis. Inclusion on ACC.org does not constitute a guarantee or endorsement by the ACC and ACC makes no warranty that the content is accurate, complete or error-free. The content is not a substitute for personalized medical advice and is not intended to be used as the sole basis for making individualized medical or health-related decisions. Statements or opinions expressed in this content reflect the views of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of ACC.