Cover Story | Recognizing and Addressing Health Literacy in Your Patients: Low Health Literacy Impacts Cardiovascular Prevention, Treatment

The patient had heart failure but had stopped taking his beta-blocker. Robert Lee Page II, PharmD, a cardiac care associate of ACC, and professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of Colorado in Denver, asked why.

"It makes me feel so tired," the patient said. "My heart feels like it's going too slow." Page looked at the man's medications and immediately realized the problem. While his patient had originally been prescribed metoprolol succinate, he'd recently been switched to carvedilol. However, no one had told him to stop taking the metoprolol succinate.

"His heart rate was in the fifties," says Page, who specializes in working with patients with heart failure.

A classic case of poor health literacy and a failure to communicate.

Defined as "the degree to which an individual can access, process, and comprehend basic health information and services to inform and participate in health decisions," health literacy has little to do with people's ability to read – although that can certainly play a role. Instead, it means how well patients understand numbers (including risk) and can navigate our byzantine health care system, communicate with health care professionals and caregivers, and make well-informed decisions about their health. Although educational level plays a role in health literacy, so, too, do cultural and social factors.2

"Is it a problem?" asks Page. "Absolutely."

Indeed, the Joint Commission released recommendations to that effect in 2008, calling on health care organizations to train their staff to recognize patients with language and literacy needs and to stress clear communication.3

Poor health literacy is associated with higher rates of emergency department visits, hospitalizations, medication nonadherence and mortality, particularly in patients with cardiovascular disease.4-6 A recent statement from the American Heart Association (AHA) stresses the relevance of health literacy to overall cardiovascular health, including prevention.6

Yet nearly half of all adults, about 90 million, demonstrate inadequate health literacy.7

"It's not just about reading," says Page. "You have to be able to obtain, process and apply the basic information that impacts your well-being and self-care so you can make appropriate health decisions. I always tell my cardiologists that if knowledge is power and if information is liberating, then education is the premise for us to go forward and improve outcomes in patients."

Health Literacy and Cardiovascular Disease

There are numerous examples of the effects of inadequate health literacy on both cardiovascular disease prevention and management. One study of 402 individuals with hypertension found that 55 percent had inadequate health literacy and did not understand that a blood pressure reading of 160/100 mm Hg was abnormal.8 Other studies find that those with poor health literacy are two-to-three times as likely to fail to reach blood pressure goals.9,10

Patients with inadequate health literacy have worse heart failure-related quality of life and knowledge about their condition, as well as a lower likelihood of self-care. They are also less likely to adhere to quality guidelines compared with those with better health literacy.11

Mayberry, et al., found that poor health literacy predicted a twofold increase in mortality and a 1.3-fold increase in readmissions after discharge for patients with acute coronary syndrome and acute decompensated heart failure. Those with poor health literacy were, on average, 12.8 percent more likely to die within a year than those with adequate health literacy.4

Another study based on a survey of 1,494 heart failure patients, 17.5 percent of whom had low health literacy, also found a two-fold higher mortality rate. These patients were older, with a lower socioeconomic status, less than 12 years of education and higher rates of comorbidities.12

In a study of 409 patients with coronary heart disease, those with marginal or inadequate health literacy were twice as likely to be nonadherent with their medications as those with adequate health literacy.13

Poor health literacy is also associated with significantly higher health care costs.

A review of health care costs in the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans' Health Administration system involving 92,749 patients found that health care costs, including pharmacy, were nearly twice as high for those with poor health literacy as those with adequate literacy ($17,033 vs $31,581).14

Communication is Key

The impact of health literacy and how to mitigate "isn't taught in medical school," Page says. "So people don't think about it until an adverse event occurs."

He recalls a transplant patient prescribed fluconazole for oral thrush. The patient returned to the clinic with severe thrush and his doctors assumed he was resistant to the medication. Page asked the patient how he was taking the medication (which needed to be sucked on like a lozenge).

"He was swallowing it or chewing it up because he didn't understand the technique," Page says. "He thought it was like any other medication. That could have been a hospital admission."

Another dangerous situation barely averted involved a patient with heart failure who took daily over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), which is absolutely contraindicated given the stress it puts on the kidneys. The patient didn't understand that Motrin and naproxen were NSAIDs and wound up hospitalized.

"You'd be surprised at the percentage of patients who are admitted or seen in the heart failure clinic who were never told this," says Page.

Yet patients are often embarrassed to ask the physician questions, studies show, feeling ashamed of their ignorance or confusion. "Patients, particularly older patients, are very good at hiding their health illiteracy," Page says. "You have to tease it out."

Addressing health literacy starts with identifying it. As the authors of a review article on the topic noted: "Assessment of health literacy should be a standard of care in patients with cardiovascular disease..."15

However, a survey of 122 hospitals in the TRANSLATE-ACS study found that just 20.5 percent routinely screened patients for low literacy, 38.5 percent selectively screened patients, and 41 percent never screened patients. Patients discharged from hospitals that routinely screened for literacy were 26 percent more likely to report six-week medication adherence compared with those who never screened. In addition, selective screening was associated with a significantly lower risk of one-year all-cause readmission compared with never-screening hospitals.16

Other studies find doctors routinely overestimate their patients' health literacy.17,18

Several tools are available to quickly assess a patient's health literacy. The most commonly used in the cardiovascular setting are the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) and the Shortened Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA).15,19

Page relies on the S-TOFHLA which, he said, takes about five minutes using the available app.

Addressing Health Literacy

"Identifying and addressing health literacy is a critical part of patient-centered care," says Kim St. Clair Seals, APRN-BC, an associate member of ACC, and president of the First Coast Chapter of the Preventive Cardiovascular Nursing Association, in Jacksonville, FL. "That means tailoring health services around an individual's needs, giving comprehensive care, fostering a healing environment and focusing on the patient as a whole."

One example is the patient St. Clair Seals saw who was supposed to walk every day but didn't. The doctor complained he was noncompliant. But when St. Clair Seals asked, she learned the patient couldn't walk because his neighborhood was so dangerous. She worked with him to find another option.

"The doctor needs to take the time to understand the patient's perceptions and their ability to understand even the written word," she says. It's also important to give patients a few minutes to process information.

A systematic review of interventions to address poor health literacy found the most effective were tailored counseling, improved provider-patient interactions, organizing information by patient preference, self-care algorithms and self-directed learning. Other strategies include materials written in plain language that emphasize key points with a large font size, and using visual items such as icons or color codes.20

Interventions can be as simple as labeling drugs to address patient literacy issue, which one study found improved adherence to hypertension and diabetes drugs fivefold in patients with low health literacy.21

Other effective interventions include:

- Take a multidisciplinary approach. Nurse practitioners, physician assistants and pharmacists receive more training in patient education and can often spend more time with patients, Page says. Even encouraging patients to ask to speak with the pharmacist at a chain drugstore can help improve understanding, he adds.

- Integrate the patient's support system in the health care process. St. Clair Seals recalls a patient with angina who told the doctor he didn't have any chest pain. Then his wife spoke up: "Of course he's not having any chest pain, he's not doing anything. He stopped walking the dog or cutting the grass." Rather than focusing on the medical problem, the better focus could be the patient's quality of life, asking: "What activities are you doing? Do you have any pain when doing them?"

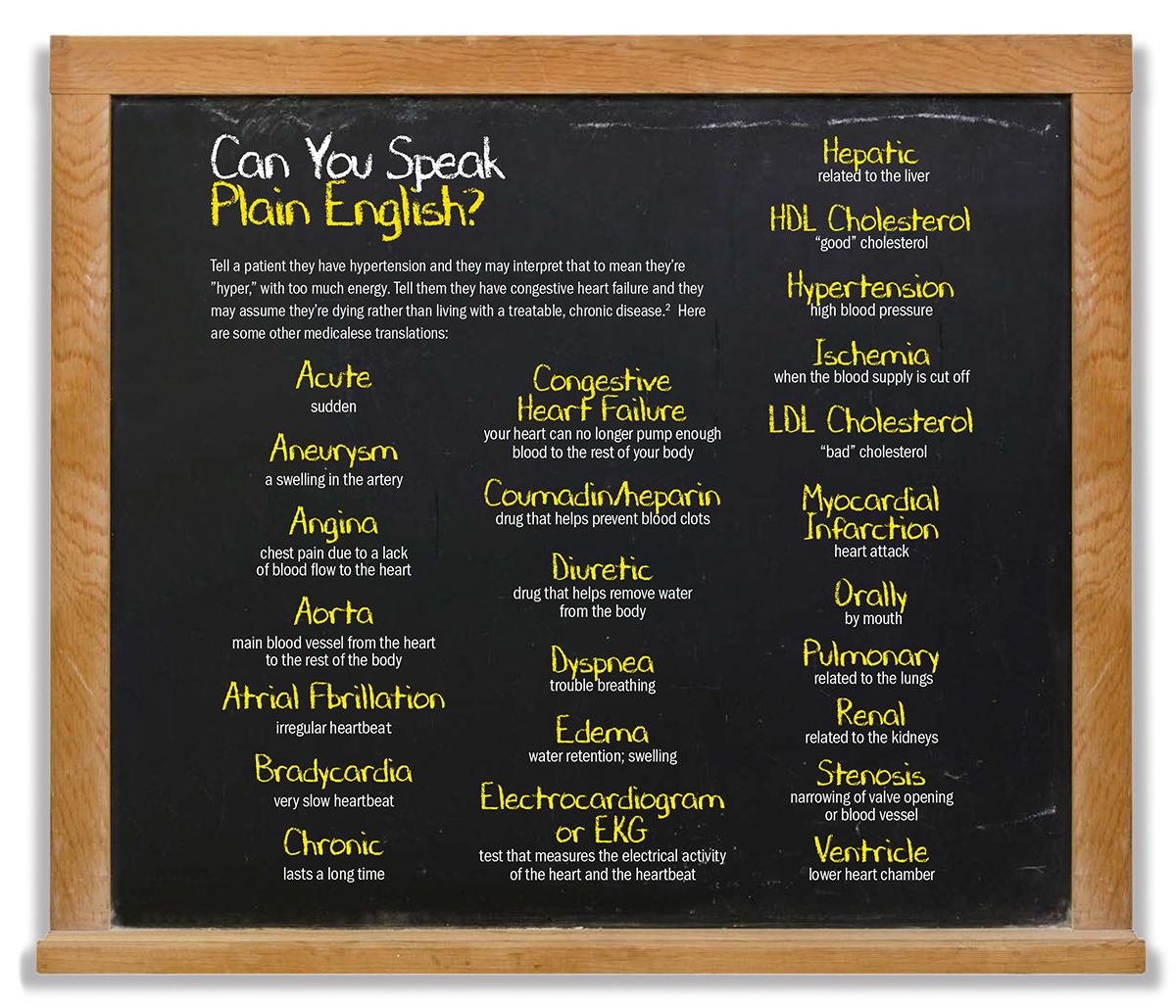

- Use plain language instead of medical jargon.

- Use teach-back and show-back techniques. This involves having the patient repeat the information or instructions.

- Limit the amount of information provided so as not to overwhelm patients.

- Use visual aids to demonstrate the disease process and management. The ACC has a plethora of patient-friendly information available for download. St. Clair Seals particularly recommends ACC's CardioSmart website and CardioSmart Explorer app, which she keeps on her iPad for patient education. She recently presented the results of a study using the app and found that not only was it clinically feasible at the point of care, but early results demonstrated it could improve the quality of care.

- Encourage patients to ask questions.

- Have patients bring their medications and check not just for interactions but ensure they can read the label and know what each is for. Always ask about over-the-counter medications and supplements.

- Follow up via phone. If you know the patient has poor health literacy, have someone in the office call to ensure they filled the prescription, are comfortable taking the medication, and/or understand all other instructions for care.

- Identify outside resources to help the patient, such as a nutritionist, pharmacist or rehab specialist.

Yes, it takes time. Yes, say St. Clair Seals and Page, it can be challenging to do during the typical 15-minute visit. But, they both say, it's worth it.

Rethinking Clinical Guidelines

The ACC currently has 119 published guidelines, expert consensus documents and appropriate use criteria. But they are just the tip of the clinical policy document iceberg, with others published by numerous organizations and cardiovascular specialty groups. In fact, one study found more than 400 such cardiovascular-related documents.1

The evidence is clear that guideline-directed care can improve outcomes.2-5 However, the evidence also shows that the delivery of such care is less than optimal.4,6-8

There are numerous barriers to the delivery of guideline-based care, including a lack of awareness and familiarity with the guidelines; knowledge gaps; discordant guideline recommendations; time constraints, established practice patterns; and lack of resources for quality improvement.7

Which is why the ACC and the American Heart Association (AHA) have embarked upon a five-year initiative designed to re-engineer how guidelines are developed and disseminated. The ultimate goal of the guideline optimization process, which is spearheaded by the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines, is to develop more dynamic, up-to-date, and user-friendly recommendations.

"We know a great deal about what should be done to achieve optimal patient care, but we have learned repeatedly that there is a gap in execution of the recommendations already published," says Patrick T. O'Gara, MD, MACC, who chairs the Task Force. "Reformatting the guidelines to make them more easily accessible and searchable would be a very important contribution to facilitating putting the recommendations into practice."

"There are clearly still some challenges to getting our guidelines to the practitioners and having them actually read," says Glenn N. Levine, MD, former task force chair. One reason is the sheer number of guidelines, he says. Another is their length, often on the order of 100 or more pages. A third reason, he adds, is that "our presentation of our recommendations has not, in some cases and formats, been optimal for busy practices in a world of Internet apps and a plethora of journals."

Although the ultimate goal is to improve guideline integration into clinical care, "we don't want to lose any of the trustworthiness of what we're providing," O'Gara says. Thus, the optimization effort is "holding fast to the principle that the guidelines need to be trustworthy and focus on facilitating their use at the point of care."

A recent update from the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines highlights four key initiatives to improve guideline development:9

- Make published guidelines shorter and more user friendly and readable.

- Focus guidelines more on actual recommendations and patient management flow diagrams and less on extensive text and background information.

- Format guidelines to allow for more facile and seamless updates. O'Gara calls this creating "living and breathing" guidelines that can be quickly updated as new studies and science emerge.

- Format "chunks" of information to facilitate integration of discrete modules of information into electronic media, fostering easier implementation at the point of care. "The modular knowledge chunk tries to consolidate and identify the most important information for busy practitioners," says Levine, "including the table of recommendations, the synopsis, and the flow diagrams, which may be all many really have time to look at."

One goal is to improve a patient's understanding of what it means to receive guideline-recommended care, notes Thomas M. Maddox, MD, MSc, FACC, who chairs the ACC's Science and Quality Committee. This, in turn, could help improve patients' health literacy.

"Health literacy gets into the idea of how a patient thinks about the benefits, risks and tradeoffs of their health care," he says, "and how it impacts their future health status and mortality. These are difficult concepts, even for clinicians who think about this every day."

Thus, improving translation of guidelines to practice requires not only optimizing the guidelines for the care team, but incorporating the patient's preferences and values into treatment decisions.

A first step in translation is dissemination through the ACC rollout of the primary prevention guideline released during ACC.19. The new guideline was disseminated in a variety of formats including print, blogs, social media and to the lay media.

This included two major presentations at the meeting; adding the recommendations to ACC's Guideline Clinical app, ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus, and the CardioSmart Hub; and launching an extensive media campaign. As a result, use of the apps was significantly higher in the week after the release and the guideline garnered the most media coverage of any study presented at ACC.19 (including late-breaking clinical trials), with 539 original articles and an additional 639 pickups.

None of this would be possible without the hundreds of hours of volunteer time, O'Gara stressed. "We are indebted to the extraordinary staff at ACC and AHA who are making this a reality," he said, "and to the professionalism that exists across our organizations."

References

- Tobe SW, Stone JA, Brouwers M, et al. Harmonization of guidelines for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease: the C-CHANGE Initiative. CMAJ 2011;183:E1135-50.

- Ellrodt AG, Fonarow GC, Schwamm LH, et al. Synthesizing lessons learned from Get with the Guidelines: the value of disease-based registries in improving quality and outcomes. Circulation 2013;128:2447-60.

- Borbas C, Morris N, McLaughlin B, et al. The role of clinical opinion leaders in guideline implementation and quality improvement. Chest 2000;118(2 Suppl):24S-32S.

- Peterson ED, Bynum DZ, Roe MT. Association of evidence-based care processes and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes: performance matters. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2008;23:50-55.

- Peterson ED, Roe MT, Mulgund J, et al. Association between hospital process performance and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2006;295:1912-20.

- Cannon CP, Hoekstra JW, Larson DM, et al. Physician practice patterns in acute coronary syndromes: an initial report of an individual quality improvement program. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2010;9:23-9.

- Roe MT, Ohman EM, Pollack CV Jr., et al. Changing the model of care for patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2003;146:605-12.

- Bottorff MB, Nutescu EA, Spinler S. Antiplatelet therapy in patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the CRUSADE national quality improvement initiative. Pharmacotherapy 2007;27:1145-62.

- Levine GN, O'Gara PT, Beckman JA, et al. Recent innovations, modifications, and evolution of ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guidelines: An update for our constituencies: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1990-8.

References

- Magnani JW, Mujahid MS, Aronow HD, et al. Health literacy and cardiovascular disease: fundamental relevance to primary and secondary prevention: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;138:e48-e74.

- National Institute of Medicine. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. 2004. Available here. Accessed Sept. 19, 2019.

- Joint Commission. What Did the Doctor Say? Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety. 2007. Available here. Accessed Oct. 9, 2019.

- Howard DH, Gazmararian J, Parker RM. The impact of low health literacy on the medical costs of Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Med 2005;118:371-7.

- Mayberry LS, Schildcrout JS, Wallston KA, et al. Health literacy and 1-year mortality: mechanisms of association in adults hospitalized for cardiovascular disease. Mayo Clin Proc 2018;93:1728-38.

- Ventura HO, Piña IL. Health literacy: an important clinical tool in heart failure. Mayo Clin Proc 2018;93:1-3.

- Institute of Medicine. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington DC: The National Academies Press;2004.

- Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM, Nurss JR. Relationship of functional health literacy to patients' knowledge of their chronic disease. A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:166-72.

- Pandit AU, Tang JW, Bailey SC, et al. Education, literacy, and health: Mediating effects on hypertension knowledge and control. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:381-5.

- McNaughton CD, Jacobson TA, Kripalani S. Low literacy is associated with uncontrolled blood pressure in primary care patients with hypertension and heart disease. Patient Educ Couns 2014;96:165-70.

- Macabasco-O'Connell A, DeWalt DA, Broucksou KA, et al. Relationship between literacy, knowledge, self-care behaviors, and heart failure-related quality of life among patients with heart failure. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:979-86.

- Peterson PN, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, et al. Health literacy and outcomes among patients with heart failure. JAMA 2011;305:1695-1701.

- Kripalani S, Gatti ME, Jacobson TA. Association of age, health literacy, and medication management strategies with cardiovascular medication adherence. Patient Educ Couns 2010;81:177-81.

- Haun JN, Patel NR, French DD, et al. Association between health literacy and medical care costs in an integrated healthcare system: a regional population based study. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:249.

- Elbashir M, Awaisu A, El Hajj MS, Rainkie DC. Measurement of health literacy in patients with cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm 2019.

- Rymer JA, Kaltenbach LA, Anstrom KJ, et al. Hospital evaluation of health literacy and associated outcomes in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2018;198:97-107.

- Kelly PA, Haidet P. Physician overestimation of patient literacy: a potential source of health care disparities. Patient Educ Couns 2007;66:119-22.

- Rogers ES, Wallace LS, Weiss BD. Misperceptions of medical understanding in low-literacy patients: implications for cancer prevention. Cancer Control 2006;13:225-9.

- Ghisi GLdM, Chaves GSdS, Britto RR, Oh P. Health literacy and coronary artery disease: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:177-84.

- Lee TW, Lee SH, Kim HH, Kang SJ. Effective intervention strategies to improve health outcomes for cardiovascular disease patients with low health literacy skills: a systematic review. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2012;6:128-36.

- Wolf MS, Davis TC, Curtis LM, et al. A patient-centered prescription drug label to promote appropriate medication use and adherence. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:1482-9.

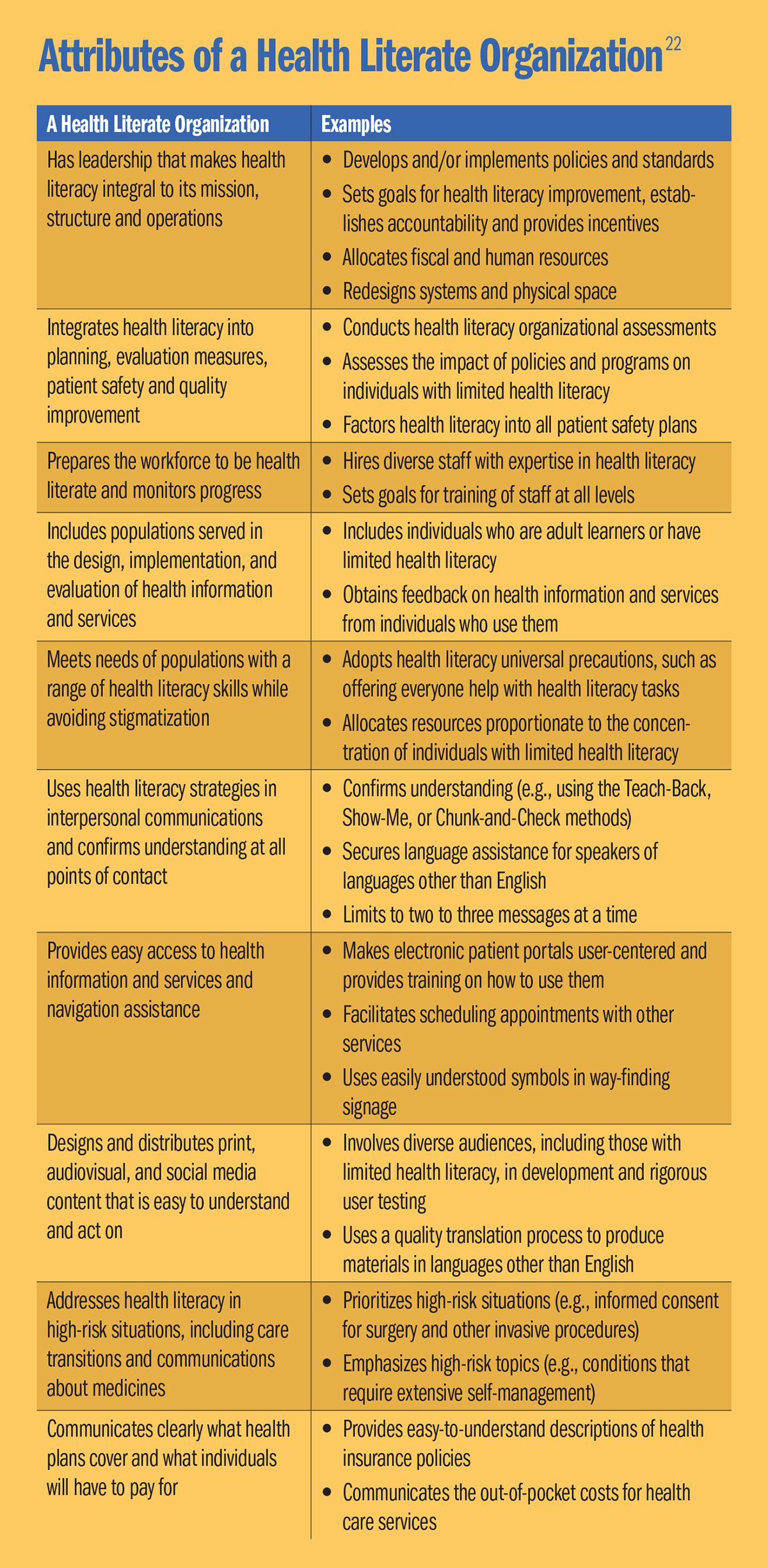

- Brach C, Dreyer B, Schyve P, et al. Attributes of a Health Literate Organization. Institute of Medicine;2012. Available here. Accessed Oct. 9, 2019.

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Cardiovascular Care Team, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Prevention, Statins, Acute Heart Failure, Hypertension, Sleep Apnea

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Acute Coronary Syndrome, Algorithms, American Heart Association, Angina Pectoris, Anti-Inflammatory Agents, Non-Steroidal, Blood Pressure, Carbazoles, Cardiovascular Nursing, Caregivers, Coronary Disease, Consensus, Counseling, Deglutition, Emergency Service, Hospital, Diabetes Mellitus, Fluconazole, Follow-Up Studies, Health Care Costs, Heart Failure, Heart Rate, Hypertension, Health Literacy, Ibuprofen, Hospitalization, Ice Cover, Medication Adherence, Mental Recall, Naproxen, Metoprolol, Patient Discharge, Nutritionists, Nurse Practitioners, Patient-Centered Care, Patient Readmission, Patient Preference, Pharmacists, Physician Assistants, Poaceae, Point-of-Care Systems, Propanolamines, Quality of Life, Schools, Medical, Self Care, Standard of Care, Social Class, Veterans Health

< Back to Listings