Feature | A 2020 View of Inflammation

Inflammation is the quintessential frenemy (a portmanteau of "friend" and "enemy"). Just about the best friend a body can have when it needs to fight off an unwelcome invader, but also a formidable enemy because of its tissue-destroying, risk-fueling qualities that see it implicated in the pathogenesis of a wide range of diseases and conditions.

Inflammation has long been regarded as an important contributor to atherosclerosis, and heart failure too, but the path towards inflammation as a therapeutic target has not gone entirely smoothly.

This Cardiology feature article will explore the inflammatory hypothesis of atherothrombosis as it is viewed in 2020, as well as its contribution to the condition on everyone's mind these days – COVID-19.

What Happened to Canakinumab?

In August 2017, attendees of the European Society of Cardiology's (ESC) annual congress were treated to an event that felt special. It was there that the cardiology world first heard the initial findings of the CANTOS trial, which showed that a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting innate inflammation via the interleukin-6 signaling pathway reduced the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events compared with placebo and independent of any effects on lipids.1

"CANTOS was very important because it was the first rigorous study that showed that inflammation is a critical player in human atherosclerosis," says Peter Libby, MD, FACC, one of the trial's principal investigators. And, not only a player, but also a target with a treatment that works.

By the time the presenters mentioned that treatment with canakinumab was associated with a clear dose-dependent risk reduction in lung cancer mortality, the audience was wide-eyed.

But then in 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration declined the requested cardiovascular indication for canakinumab, citing insufficient data. When European regulators subsequently asked for more evidence to support the indication there, Novartis withdrew their request rather than comply.

"The cancer benefit really changed the course for the sponsor," explains Libby. "Novartis afforded Paul M. Ridker, MD, MPH, FACC, and myself a wonderful opportunity to explore this hypothesis about inflammation being a fundamental driver of atherosclerosis, but they're basically, like most drug companies these days, very much focused on oncology.

When CANTOS showed them there was a potential cancer benefit in the exploratory analysis, they rushed to put resources into the cancer domain, and with that they made the decision not to pursue the cardiovascular indication" he says. There are currently a handful of trials ongoing looking at canakinumab as a cancer treatment.

Soon after, methotrexate, a cheaper and simpler drug that works by different molecular pathways and targets less relevant in pathogenic signal cascades in atherosclerosis,2 flunked out in the CIRT trial.

Possibly, says Libby, "because methotrexate doesn't have a benefit in the context of atherosclerotic disease, or possibly because the population that was enrolled didn't have enough baseline inflammation."

In an interview, Libby points out that IL-1 blockade and canakinumab may not be dead. He doesn't expect Novartis will compromise on the price for canakinumab, particularly not if the drug shows continued promise in oncology. But it's possible that someone could come up with a biosimilar anti-IL-1 and there are several other agents in development that attack the same pathway.

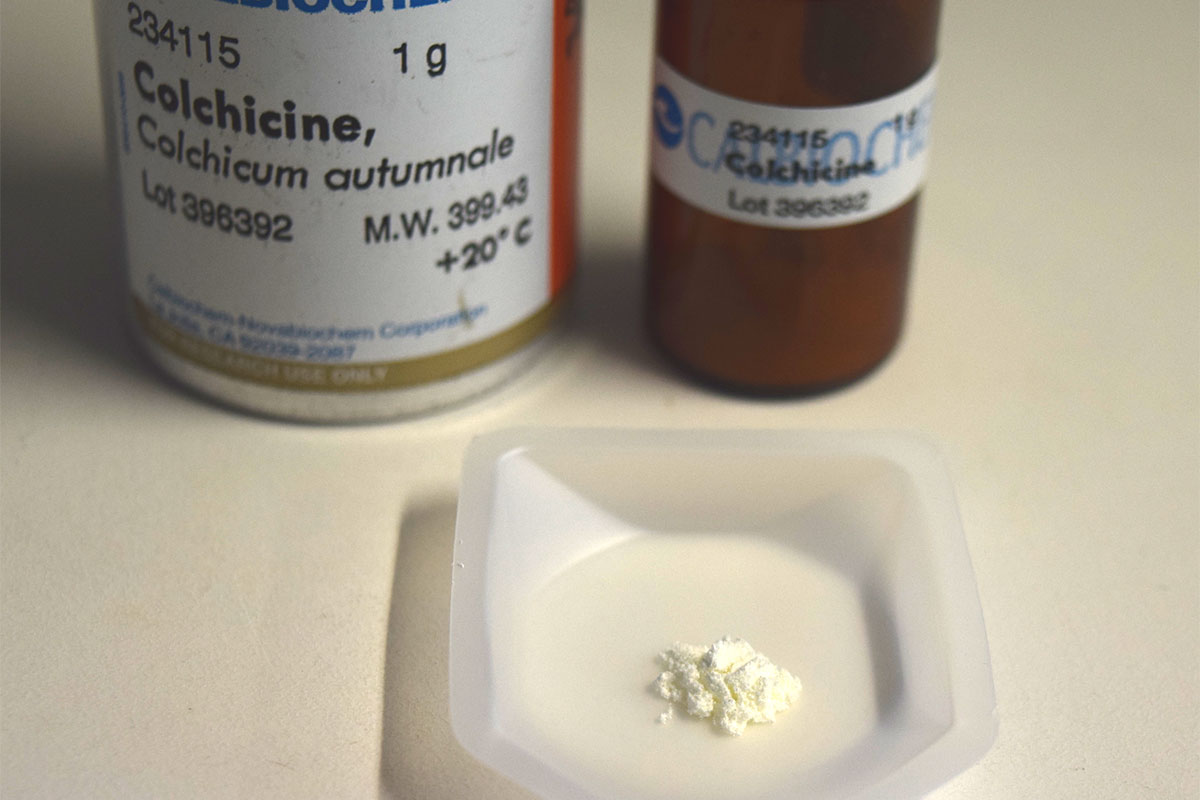

"I'm very confident that we will have anti-inflammatories to deploy in clinical practice in the coming years, and it's looking like colchicine may be the first one," says Libby.

Colchicine to the Rescue

With canakinumab and methotrexate out of the running, all eyes turned to colchicine, a plant-based, inexpensive, potent anti-inflammatory long used to treat gout and other inflammatory conditions.

It has also transformed the treatment of pericardial disease in the last several years, says Libby, after a handful of trials provided robust evidence of its safety and effectiveness for both acute and recurrent pericarditis.3

"The hope is that colchicine will turn out to be a low-cost, readily available, reasonably well tolerated anti-inflammatory agent that we can use in our cardiovascular patients," says Libby.

Just this past November, Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, FACC, presented and published initial findings from the COLCOT trial.4

COLCOT enrolled 4,745 patients who were within 30 days of a myocardial infarction (MI). Those randomly assigned to receive low-dose colchicine (0.5 mg once daily) had a 23% lower risk of the composite of death from cardiovascular causes, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke or urgent hospitalization for angina leading to coronary revascularization (5.5% vs. 7.1% for placebo; p=0.02). This reduction in risk bumped up to 29% in patients with better adherence.

To Tardif, no tears need be shed over canakinumab.

"Colchicine is orally administered while canakinumab requires an injection; colchicine is less than a dollar a day in most places and canakinumab costs tens of thousands of dollars per patient per year; and low-dose colchicine is safe and well tolerated, while canakinumab was associated with a small increase in the risk of septic shock that may lead to death."

And the benefit of colchicine as seen in the COLCOT trial is actually larger than that seen in CANTOS, he adds.

Based on pricing alone, colchicine has great appeal. Even in the U.S., where colchicine has been subject to some pricing mischief, the cost per pill is between $4 and $6.5,6 In other places, the cost is but pennies per pill and data presented at ACC.20/WCC Virtual showed excellent cost-effectiveness.7

"The COLCOT trial was really very impressive. I was surprised both by the magnitude of the clinical benefit with low-dose colchicine and also by the tolerability," says Libby.

"There was a little pneumonia signal, and this harkens back to the infection signal we saw in CANTOS and reaffirms that you pay a price when you inhibit the inflammatory system," he adds.

The drug was generally well-tolerated, causing diarrhea in about one in ten patients (p=0.35 compared with placebo). Pneumonia was reported as a serious adverse event in 0.9% of the patients in the colchicine group and in 0.4% of the placebo group (p=0.03). Other common complaints with the drug were nausea and flatulence (reported in 1.8% and 0.6%, respectively), both of which were more common in the treatment arm compared with placebo.

"We're waiting with bated breath for the ESC 2020 Congress when the LoDoCo2 trial will be presented," says Libby.

"If we have two independent trials that show a benefit of colchicine, I think it's going to change practice, and the proof of principle of CANTOS may come to clinical fruition with colchicine," says Libby.

LoDoCo2, one of several colchicine studies slated for the ESC Congress, is a multicenter, double-blind, event driven trial in which 5,522 patients with stable coronary artery disease have been randomized to colchicine 0.5 mg daily or matching placebo on a background of optimal medical therapy.

The study will have 90% power to detect a 30% reduction in the composite primary endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI, ischemic stroke and ischemia-driven coronary revascularization.

LoDoCo2 is complementary to COLCOT.

"We studied patients within 30 days of an MI and they are studying patients with stable coronary artery disease," says Tardif.

"Given what we've seen so far with colchicine, I have little doubt that LoDoCo2 will be positive, in which case I believe there will be a sea change."

At the Montreal Heart Institute, Tardif and colleagues are already systematically screening patients in the coronary care unit and considering colchicine before discharge for those who fit the COLCOT criteria.

Targeting Inflammation in COVID-19

If we've learned anything about targeting inflammation, now is the time to apply that knowledge to the hot mess that is COVID-19.

On the laundry list of cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 are myocarditis, myocardial injury, acute coronary syndromes (type 1 and 2 MI), arrhythmias, and cardiomyopathy.8 Myocardial injury, with elevated troponins, has been noted in 20-30% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients, and in up to 55% of those with preexisting cardiovascular disease.8

The presence of elevated troponins has been linked to an increased risk of severe disease and death.

Perhaps even more concerning, in a study released in late July, German researchers found that from a group of 100 relatively younger patients (median age, 49 years) who recovered from the disease – the majority of them (67%) without needing hospitalization – cardiac MRI at a mean of 71 days after confirmed diagnosis revealed abnormal cardiac findings in 78% and imaging evidence of active myocardial inflammation in 60%.9

High-sensitivity troponin T values were detectable (3 pg/mL or greater) in 71% of recently recovered patients and significantly elevated (13.9 pg/mL or greater) in an additional 5%.

In an editorial that accompanied the research, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MACC, and Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, FACC, suggest the real possibility that "cardiomyopathy and heart failure related to COVID-19 may potentially evolve as the natural history of this infection..."10

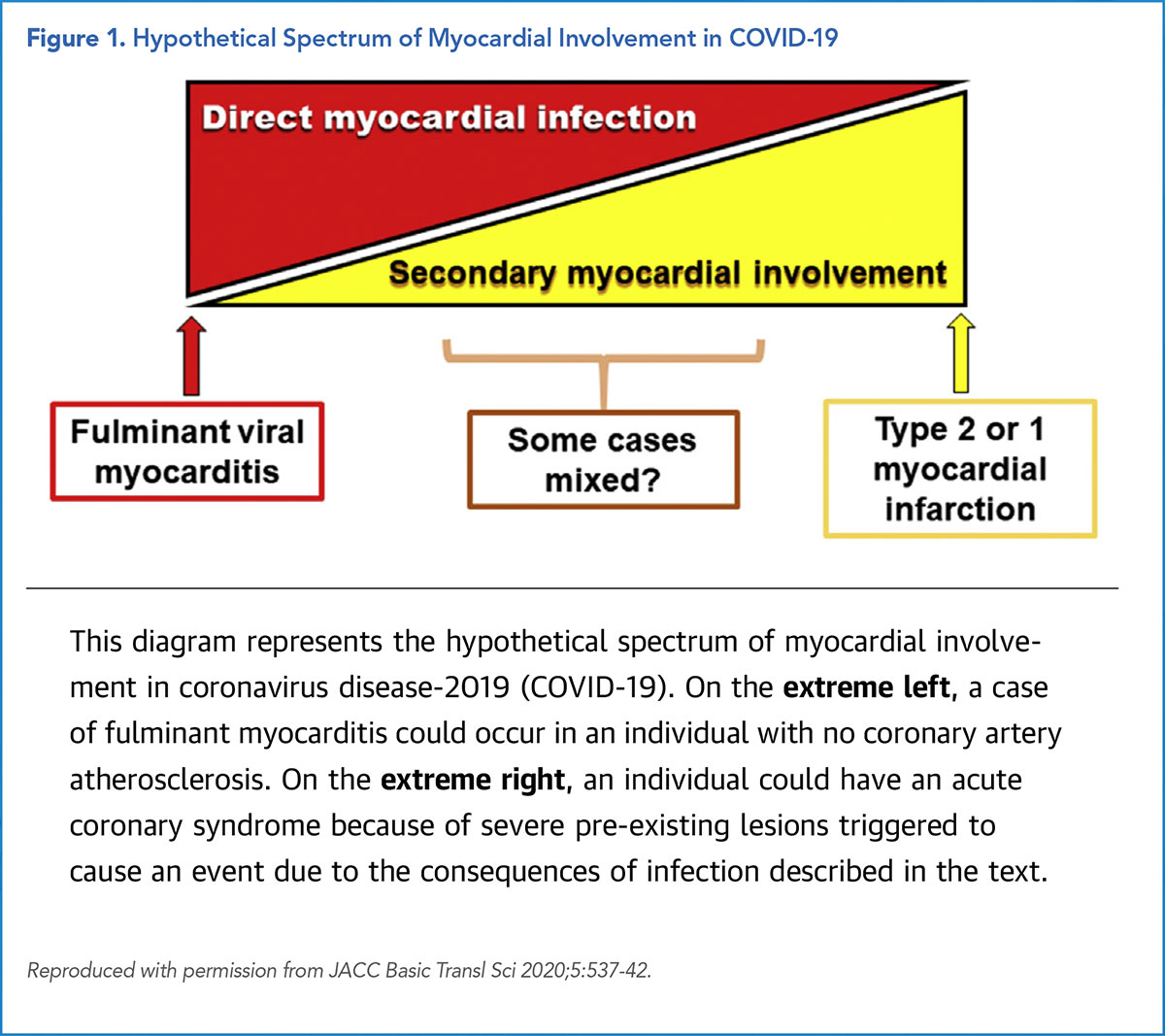

Cardiac injury in COVID-19, says Libby in a recent article, can be a result of direct viral infection (fulminant myocarditis), or can be related to other causes, including increased oxygen demand secondary to tachycardia and fever, both cardinal signs of infection.11

Another option is that infection at remote sites cause cytokine release that activates the microvascular endothelium, "predisposing to vascular abnormalities, augmented thrombosis, reduced fibrinolysis, increased leukocyte, adhesion," and other circulatory dysfunction.

"At one end of the spectrum, a young individual with pristine coronary arteries might suffer severe myocardial injury due to a fulminant myocarditis caused by direct infection with COVID-19 (Figure).11

At the other extreme, a person with advanced coronary atherosclerosis could suffer a type 1 or type 2 acute MI without direct viral infection of cardiac cells (Figure)," says Libby. He suspects cardiologists are more likely to see patients with the second scenario.

With no time to waste, several anti-inflammatories are being tested against COVID-19, including drugs designed to block the overzealous IL-1 and IL-6 response to the virus, like tocilizumab, siltuximab, and Anakinra.

At least four trials are testing canakinumab, and among the other various agents being considered is, once again, colchicine.

The mechanistic plausibility is there: colchicine inhibits, among other things, the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, activation of which has been implicated in SARS-CoV infection.12

"It was shown very elegantly in a 2015 paper in Virology that the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in SARS-CoV-1. Given the genomic similarities, it's very likely that SARS-CoV-2 does the same thing, so we feel quite confident that colchicine should help prevent the inflammatory storm in COVID-19 patients," says Tardif.

Apparently, others agree: a search of clinicaltrials.gov shows that colchicine, either alone or in combination with other agents, is currently being tested in COVID-19 in 16 different trials.

The early data are promising. In a small, open-label Greek study, those who received colchicine had significantly improved time to clinical deterioration, although not significantly lower high-sensitivity troponin or C-reactive protein levels.13

Tardif's group is running the largest trial of colchicine in COVID-19, partially funded by a grant from the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator via the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

COLCORONA is a contact-less at-home study that will enroll 6,000 patients just diagnosed with COVID-19 (and with at least one other risk criterion) and will test whether colchicine will reduce the composite of death or the need for hospitalization due to COVID-19 infection.

"When you look at what is happening in the natural history of COVID-19, by the time patients develop complications of the disease, somewhere between days five and 14, you're already at a stage where viral replication is going down and it is exactly the time where the host immune response to the virus is kicking in. And so, we believe that we should be targeting the host immune response rather than thinking about the virus, because viral replication is already going down," says Tardif.

The sample size will allow researchers to detect if there is a reduction of at least 25% in the risk of events, taking into account a 7% event rate in the placebo group. Follow-up phone or video assessments will occur at 15 and 30 days following randomization for evaluation of the occurrence of any trial endpoints or other adverse events.

While he acknowledges the concern that tamping down the immune response might leave the patient vulnerable to rampant viral replication, Tardif says that, so far, things are looking promising for their early-treatment approach. In June, an interim analysis by the independent data safety and monitoring board indicated that the trial had surpassed the futility stage and was cleared to continue, without any expressions of concerns regarding safety.

COLCORONA is currently enrolling patients in Montreal, British Columbia and Ontario in Canada; New York City and the tri-state area, Miami, California and Texas in the U.S.; and Madrid, Spain, with more sites to come.

Of course, beyond finding drugs that work, the trick is to figure out who to treat and when. Libby hopes trials going forward will be more carefully conducted than has been seen thus far.

"We need to have a national initiative to do properly powered, properly designed, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials in order to answer these questions, because people are dying with thrombotic complications, people are dying of respiratory complications, and we have agents that could address these different baskets. And we have up-front antivirals for the earlier phases of disease. But we really need to do the proper trials to find our way through this thicket."

Even with colchicine, while he acknowledges the mechanistic plausibility and the early trial findings, Libby is waiting for more evidence.

"I want to see a proper trial of colchicine before we jump in, particularly because there is a real downside with anti-inflammatories in patients with advanced COVID-19 who are put on ventilators. When you put someone on a ventilator and you also tamp down their defenses for keeping the airways healthy, they can get bacterial superinfections," Libby cautions.

Hopefully, the answer Libby (and so many others) seeks is coming soon. Tardif and colleagues have promised to release the results of COLCORONA within 48 hours of the 6,000th patient finishing their 30-day treatment course.

"Of course, I'm still blinded to the results, but I think it's looking very good for colchicine," says Tardif.

"Thirty days after we are fully enrolled and 48 hours after the last patient visit, we will announce to the world whether this drug works for COVID-19."

With around 2,000 patients randomized already (as of late July), this could happen by early September.

References

- Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1119-31.

- Palmer RD, Vaccarezza M. Front Cardiovasc Med 2019;6.

- The Use of Colchicine in Pericardial Diseases. American College of Cardiology. Available here. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- Tardif J-C, Kouz S, Waters DD, et al. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2497-2505.

- The Cost of Colchicine. Mitigare. Available here. Published May 26, 2020. Accessed July 26, 2020.

- Kesselheim AS, Solomon DH. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2045-47.

- Samuel M, Tardif J-C, Khairy P, et al. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2020;May 14:qcaa045.

- Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, et al. Nat Med 2020;26:1017-32.

- Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, et al. JAMA Cardiol 2020;July 27:[Epub ahead of print].

- Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. JAMA Cardiol 2020;July 27:Epub ahead of print.]

- Libby P. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2020;5:537-42.

- Nieto-Torres JL, Verdiá-Báguena C, Jimenez-Guardeño JM, et al. Virology 2015;485:330-39.

- Deftereos SG, Giannopoulos G, Vrachatis DA, et al. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(6):e2013136.

Clinical Topics: COVID-19 Hub, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), Lipid Metabolism, Novel Agents, Heart Failure and Cardiac Biomarkers

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Colchicine, Biosimilar Pharmaceuticals, Cost-Benefit Analysis, Interleukin-6, Interleukin-6, Methotrexate, Shock, Septic, COVID-19, United States Food and Drug Administration, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Lipids, Atherosclerosis, Antibodies, Monoclonal, Myocardial Infarction, Coronary Artery Disease, Angina Pectoris, Myocarditis, Troponin, Troponin T, Interleukin 1 Receptor Antagonist Protein, C-Reactive Protein, Inflammasomes, Coronary Care Units

< Back to Listings