Cover Story | Pulmonary Hypertension and the Right Ventricle: Forgotten No More

After decades of playing second fiddle to its more red-blooded, muscular, high-pressure partner on the left side of the heart, the weaker, low-pressure right ventricle (RV) is finding its independent identity both as a formidable prognosticator, with a strong impact on mortality in cardiovascular health, in heart failure (HF) across the ejection fraction spectrum, and as a major player in outcomes in valvular heart failure intervention.

With a new definition of pulmonary hypertension (PH), fresh guidelines and some emerging treatments, as well as better appreciation for RV adaptation and maladaptation, the RV is more often demanding its own specialized attention, with the promise of improved survival for patients with left heart cardiac diseases that impact the RV.

This month's Cardiology cover story explores the growing issue of RV failure and its management, focusing on how to spot RV dysfunction and when to refer patients for specialized care, concepts likely to be encountered more frequently in general cardiology, internal medicine (and pulmonary) practices.

PH Epidemiology and Key Paradigm Shifts

PH is a global health issue, presently estimated to affect about 1% of the global population.1 The very definition of PH has changed in recent years, and with it has come a new focus on early diagnosis of the disease and new hope that the disease course can be changed from one punctuated by elevated morbidity and shortened lifespan to one where early diagnosis and treatment extends survival.

PH is now defined by a mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) >20 mm Hg at rest, down from the classical definition of mPAP >25 mm Hg. The change is a refinement based on a substantial amount of evidence indicating that clinical risk begins at an mPAP above the upper limit of normal of 19-20 mm Hg.

Lowering the diagnostic threshold captures more at-risk individuals, but it should be noted that an mPAP >20 mm Hg alone is not pathognomonic for PH. Elevated PAP occurs in response to many disease processes (such as left HF, hypoxic pulmonary disease), as well as physiological states that increase cardiac output (e.g., exercise, pregnancy, high output states of thyroid disease, shunts, cirrhosis), some of which may become pathological pulmonary vascular disease.

Classifying the etiology of elevated pulmonary pressures rests on the underlying hemodynamic values, differentiating pre-capillary PH with pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) >2.2 (previously 3) Woods units (WU), whereas a post-capillary component is indicated by a pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP) >15 mm Hg and a normal PVR, and combined pre- and post-capillary PH (Cpc-PH) is characterized by an elevated pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) and PVR >2.2.

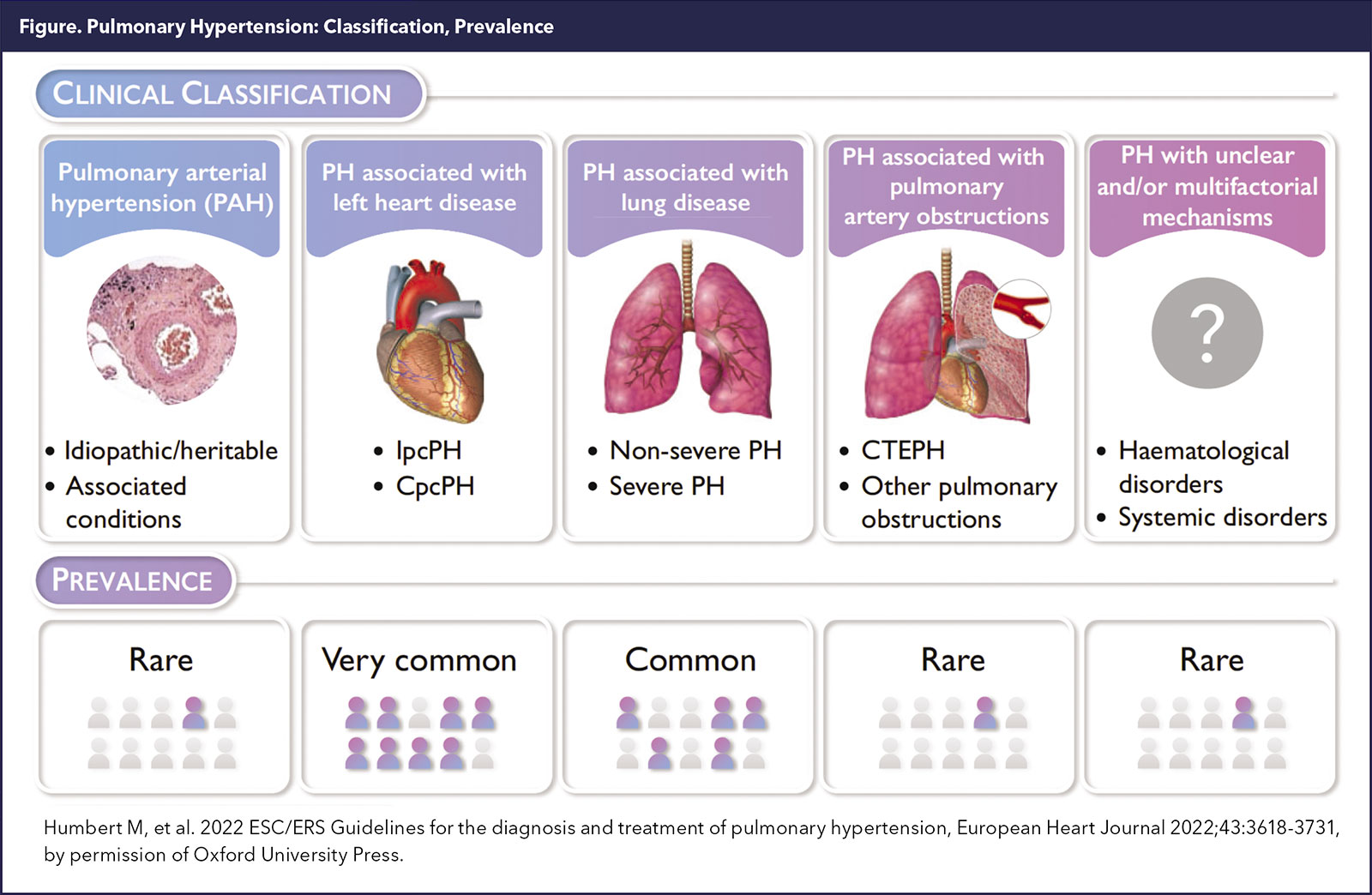

PH is a heterogeneous disease with high morbidity. Vascular changes can be characterized depending on the underlying cause and typically its World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension (WSPH) classification.

World Health Organization (WHO)/WSPH Group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) demonstrates pathogenic remodeling of distal pulmonary arteries with intimal and medial hyperplasia, which (more so in idiopathic, genetic, HIV, methamphetamine, Eisenmenger patients), may ultimately result in the most pathological plexiform lesions.

– Evelyn M. Horn, MD, FACC

Scleroderma-associated PAH may be more associated with vascular fibrosis, generally without plexiform lesions and possibly a degree of pan-vasculopathy; some of the other connective tissue-associated forms may have some degree of vasculitis. The functional (congestive) vasculopathy resulting from pulmonary venous hypertension in the setting of left atrial hypertension demonstrates venous remodeling sometimes akin to pulmonary veno-occlusive disease in addition to the arterial changes.

The WHO/WSPH recognizes five broad PH clinical categories (Figure 1). PH related to left heart disease (PH-LHD) and lung disease are by far the most prevalent.1

Dyspnea and mildly reduced exercise capacity may be indicative of early PH. Other symptoms may include fatigue, palpitations, exercise-induced light-headedness, abdominal distention and nausea, and weight gain. In patients with advanced disease, symptoms include chest pain, syncope and symptomatic right HF.

Because PH is often overlooked or diagnosed late, a high index of clinical suspicion is needed to ensure appropriate diagnosis and clinical management of patients.2

The new 2022 guidelines on the management of PH, issued by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Respiratory Society (ERS), simplify the main diagnostic algorithm for PH using a three-step approach, from suspicion by first-line physicians seeing a patient with unexplained dyspnea or signs/symptoms raising a concern of PH, to noninvasive cardiac and lung testing, in particular echocardiography, and, finally, confirmation with right heart catheterization (RHC) at a PH center.1

"Certainly, any patient in whom PAH or chronic thromboembolic PH (CETPH) is suspected needs to be fast tracked for a comprehensive PH work-up at a PH Center," says Evelyn M. Horn, MD, FACC, director of advanced heart failure and pulmonary vascular disease at the Perkin Heart Failure Center of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City.

PH Associated With Left Heart Disease

PH in a patient with left-sided cardiac disease, classified as Group 2 PH using the WHO's classification scheme, signals an unfavorable turn in the natural history of the disease.3

"These patients tend of have a lot of nausea, gastrointestinal symptoms and shortness of breath when they develop RV dysfunction as either a response to Group 2 PH or due to their underlying cardiomyopathy. I like to throw the kitchen sink at these patients to see if I can get them feeling any better. Often the most useful approach is aggressive diuresis," says Jessica H. Huston, MD, FACC, an advanced heart failure and transplant cardiologist and pulmonary hypertension specialist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

– Jessica H. Huston, MD, FACC

PH-LHD is likely the most prevalent form of PH, accounting for at least 50% of all PH cases. It's estimated that the prevalence of PH is about 50% in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and as high as 80% in those with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

Like the other forms of post-capillary PH, PH-LHD is defined by an mPAP >20 mm Hg and a PAWP >15 mm Hg. And it is associated with HF across the spectrum of ejection fractions, valvular heart disease, and congenital/acquired cardiovascular conditions leading to post-capillary PH.

Risk factors for PH-LHD include older age, systemic hypertension, obesity, glucose intolerance or prior coronary intervention. There are some important differences in how PH-LHD disease presents. Multiple phenotypes of HFpEF occur. Clinicians often see the PH-LHD phenotype in thin elderly patients or coexisting in those with metabolic syndrome and obesity.3

In all cases, the primary driver of PH is elevated left-sided cardiac filling pressures driven by impaired left ventricular (LV) relaxation and filling impacting backward transmission of elevated left atrial pressure to the venous system, capillaries and arteries, and, ultimately, to the right heart.

Don't Delay Diagnosis and Referral

With the lowered threshold for diagnosis and the possibility of disease-modifying treatments, early diagnosis is more important than ever.

"Delay in treatment is a big issue in PH. For some patients, if their diagnosis is delayed, they will never catch up," says Horn. But PAPs are not the sum total of this disease, she adds. Thus, it's important to consider risk factors along with other signs and symptoms when thinking about PH in a patient with HF.

"I think about elevated pressures in terms of the 'company it keeps' – left and right atrial size, ventricular function and interdependence. If someone has an elevated PAP and reduced EF, you'll likely assume the elevated pressure is from the HF," says Horn. However, she cautions that it may be easy to miss a diagnosis of Group 2 PH in a patient with HFpEF who has a normal EF but some diastolic abnormalities on echo. More nuanced assessment and further testing may be needed to tease this out.

"Similarly, if a patient has a systemic pressure of 150 mm Hg and some mild PH on echo, that is less scary. Start by treating the systemic hypertension and see what happens with the pressure. But if that patient has an elevated PA pressure and a systemic pressure of 90 mm Hg, it's a much different story," says Horn.

But mostly, and crucially, she adds, don't delay a referral to a PH specialist or a Comprehensive PH Care Center if there's a suspicion of PH or, worse, RV failure. PH, particularly more severe forms of PH like PAH and CTEPH, for which endarterectomy is potentially curative, requires highly specialized management.

– Jessica H. Huston, MD, FACC

The PH Care Centers initiative of the Pulmonary Hypertension Association (PHA) identifies centers with expertise in PH that have demonstrated an ability to both properly diagnose and manage these complex patients. Accreditation is rigorous and these centers offer the full range of advanced PH therapies, including intravenous and subcutaneous prostacyclin derivatives and have early referral protocols for CTEPH care, lung transplantation and rehabilitation centers. The PHA also maintains a directory of physicians, typically cardiologists, pulmonologists or rheumatologists, who have a special interest in PH.

Says Huston, "It's never too early to refer to a PH specialist. If somebody is showing elevated filling pressures or elevated pulmonary pressures on their echocardiogram, that's a person whose mortality is higher than somebody who has totally normal pulmonary pressure. I like to see people if there is a suspicion of PH or they have risk factors for PH, even if they appear to have a normal echocardiogram."

Certainly, if there's concern a patient has PAH and has an estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) of 45 mm Hg on echo with symptoms, there should be an immediate referral to a PH specialist, before the RV is struggling. "We're much better equipped to help them if we see them earlier."

While non-specialists can start the diagnostic process with echocardiography, right heart catheterization is required to confirm the diagnosis, clarify the PH subtype and stage disease severity.

The dilated dysfunctional RV, once it's bad, is easy to see on echocardiography. But echo is not great for measuring intermediate degrees of RV function. Traditionally, TAPSE – tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion – a one-dimensional measure of the annulus moving in one plane – is for a ventricle that's concentric in shape. But Huston notes that TAPSE alone doesn't provide an accurate assessment of the whole RV when measuring only one plane.

MRI does a much better job of informing on RV function, although it's less likely to be available, she adds, particularly in a more acute patient. "A right heart catheterization is necessary for definitive diagnosis of PAH. Knowing the right atrial pressure is high can provide a lot of information on these patients as a reflection of what the RV is doing. On echo we tend to focus too much on ejection fraction, which even in the LV is a wholly oversimplified measure of how well the ventricle is functioning," says Huston.

Managing RV Failure in PH: Giving the Right Heart Some Love

Pulmonary Hypertension Clinical Collection

Click here to access this collection to keep up with the evolving science.

Multimodality Imaging of RV Function: More Resources

Click here to read the recent JACC Scientific Statement that reviews the standard and novel imaging methods for assessing RV function and the impact of the parameters on different disease outcomes, and more.

RV failure is a recognized complication of primary cardiac and pulmonary vascular disorders and is associated with a poor prognosis. Understanding RV physiology is paramount for adequate management of patients presenting with RV failure.

"Traditionally, cardiologists not specialized in the right heart tend to not consider the RV unless they're considering advanced HF therapies like heart transplantation or left ventricular assist device implantation. This is a mistake," says Huston.

"With the RV, first there is dilation and then systolic dysfunction. So, when I see the RV is getting very dilated on echo, that's a sign of high afterload, whether it's from pulmonary vascular remodeling or congestion," she explains.

"The biggest thing to look for is the interplay between the two ventricles. If you see septal flattening, where the RV is really kind of commanding more space and infringing on the LV, and RV pressures are approaching or exceeding LV pressures, there is a failing RV phenotype and a sign that the pulmonary vasculature is the primary problem, even if the LV doesn't look completely normal," Huston says.

Adds Horn, "In LHD, we know that PH and RV dysfunction have negative prognostic value. But in order to better understand the progression of disease in these patients and when or how to intervene, we need to better phenotype PH in LHD. Why some patients have a significant pre-capillary component and others are primarily congestive is only beginning to be better investigated now."

Management of PH-LHD mostly involves optimizing treatment of the underlying cardiac disease, whether it is HF or valvular heart disease. Guideline-direct medical therapy (GDMT) for HF has salutary effects on the RV, says Huston. GDMT and PAP-guided therapies should include novel therapies such as angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors.

Management of comorbidities, such as sleep apnea and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is also essential in patients with PH, along with supportive therapies like diuretics and oxygen.

"We are often taught that the RV is preload dependent, and that giving more fluid will be helpful. But generally when specialists see these patients, they are overly tanked up – in other words, off the Starling curve – and in need of diuresis," Huston says. There is a sweet spot for their venous pressure and volume overload leads to more RV dilatation and more constraint via the pericardium and more right to left septal shift with diminished LV filling.

Be Cautious About Tricuspid Repair

When it comes to tricuspid valve repair in these scenarios, Horn urges more caution. "If the tricuspid valve is leaky because the valve is dilated and the annulus is dilated from RV dysfunction and RV afterload, the valve isn't the problem – the RV-PA is the problem," she says.

– Evelyn M. Horn, MD, FACC

"In an era when we're focusing on structural heart interventions inclusive of tricuspid valve interventions for severe tricuspid regurgitation, it is imperative to assess for PH and/or RV failure phenotypes as ones where we should not proceed with a valve intervention before a HF/PH specialist helps with the assessment," Horn adds.

Applying a clip to the tricuspid valve, as shown in the TRILUMINATE trial to improve quality of life and functional status (but not survival), may adversely remove a compensatory "pop-off" mechanism by the RV.4 Inappropriate assessment of RV-PA coupling and tricuspid valve regurgitation could increase the RV pressures.

"A patient with PH, whatever etiology it might be, should not readily be sent for tricuspid valve repair," says Horn.

The problem can be even worse if the patient is sent for surgical tricuspid repair when the real problem is the RV, notes Huston. "Undergoing a large cardiac surgery in RV failure and PH, can further beat up the RV in a setting where the valve was not the primary problem."

"I think it's a very nuanced population that is appropriate for tricuspid repair and it requires teasing out carefully whether the problem is the valve or the RV," adds Huston. "We have all seen improved tricuspid regurgitation with successful treatment of PH. Hence here too the HF/PH specialist needs to be a part of the Heart Team making these decisions." For the most part, for most patients with elevated pulmonary pressures and PAH or PH-LHD, the valve is not the problem. It's everything else that's causing the valve to leak that is the problem.

New Treatments Needed

Despite its prevalence, there are essentially no established treatments for PH-LHD. Guidelines recommend against the use of pulmonary vasodilators and early experiences with using PAH-specific therapies in PH-LHD have been disappointing.

"The right heart is a can of worms because there are so many things that can cause right HF and it's all bad when you get there," Huston tells Cardiology.

"It's not like with LV dysfunction, where we have guideline-directed therapies that could make it better. There's never any easy right HF and often we are seeing PH with a lot of comorbidities."

Beyond the current recommendations to optimize GDMT, including novel therapies, managing aortic and mitral valvular issues as well as other comorbidities such as obstructive sleep apnea and renal failure patients with fistulas, new targeted therapies are needed. Several are in development.3

"PH traditionally has sat diagnostically and care-wise in between cardiology and pulmonology, with most cardiologists who take care of PH being heart failure specialists," says Horn. "More cardiologists showing more interest in the right heart will improve early diagnosis and ultimately outcomes in patients with PH."

Sotatercept: New Hope For PAH

WHO/WSPH Group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is an uncommon yet progressive disease characterized by marked narrowing and stiffening of the pulmonary vascular bed and a progressive rise in the pulmonary vascular load, leading to hypertrophy and remodeling of the RV.

PAH affects 25 individuals per 1 million population in Western countries, with an annual incidence of two to five cases per million.5 Despite some advances, and with U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications in three major categories (endothelin receptor antagonists, cGMP/phosphodiesterase inhibitors, prostacyclins) that enhance exercise capacity, improve quality of life and slow disease progression, PAH still carries significant disease-associated morbidity and mortality.

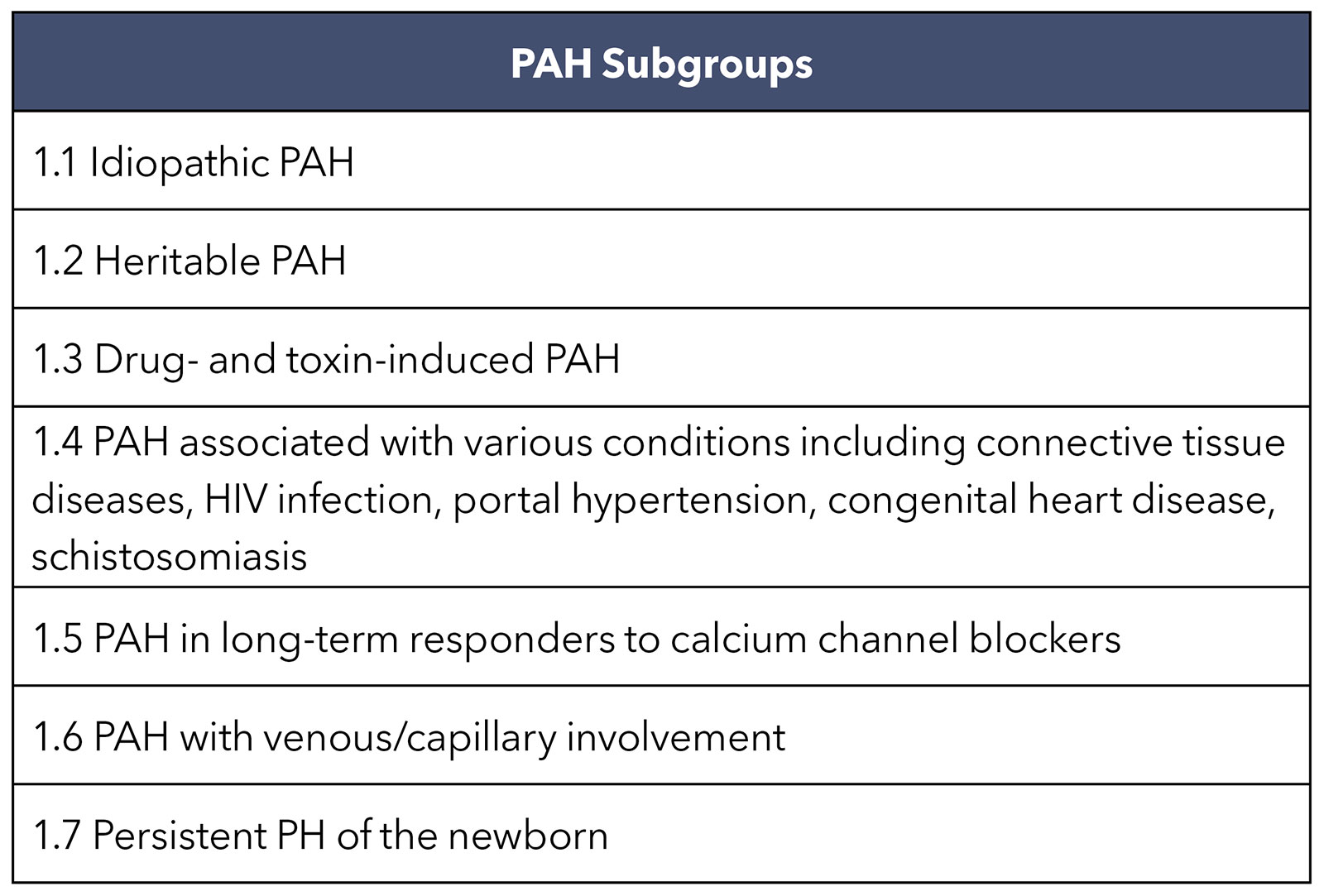

Group 1 PAH is divided into seven subgroups (Table), with most cases in the developed world classified as idiopathic or heritable, followed by PAH associated with a connective-tissue disease or exposure to drugs such as methamphetamine. With an estimate of 50 million users worldwide and lower five-year event-free survival compared with idiopathic PAH, methamphetamine-associated PAH is a growing concern.6

At one time, the demographic profile of PAH focused on younger women of childbearing age as the prototypical patients with idiopathic PAH. Today, however, this is no longer the case. The average age of patients with a new diagnosis of PAH in clinical trials is 53 years and while prevalence remains female predominant, the sex ratio in older patients is balanced.6

In recent years, there has been a shift in the approach to treating PAH from prolonging survival in advanced stages to early diagnosis and achieving goal-directed treatment benchmarks.

By far the most new and exciting treatment for PAH is sotatercept, a fusion protein and activin signaling inhibitor biologic proposed to modify the disease by targeting adverse remodeling and excessive proliferation of cells in the pulmonary arteries.

The STELLAR trial, presented as a Late-Breaking Clinical Trial at ACC.23/WCC and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, was a multicenter, double-blind, phase 3 trial in which 323 adults with PAH (mean age, 48 years; 79% female; 89% White) receiving stable background therapy were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous sotatercept or placebo every three weeks.7 Over half of patients (58.3%) had idiopathic PAH and 18.3% had a heritable form.

The mean time from PAH diagnosis was 8.8 years, 40% of patients were receiving prostacyclin infusion and 62.5% were on triple therapy at baseline. Mean PAP was 52.2 mm Hg.

The observed mean change from baseline at week 24 in the six-minute walk distance (6MWD) was an impressive +40.1 m for sotatercept and –1.4 m for placebo. For the prespecified analysis of the primary endpoint, the median change from baseline value for 6MWD, sotatercept was clearly superior to placebo (34.4 m vs. 1.0 m; p<0.001).

In addition, eight of nine prespecified secondary endpoints favored treatment with sotatercept, including a multicomponent improvement endpoint, WHO functional class, disease biomarkers, risk scores, hemodynamics and patient-reported outcomes. The sotatercept group saw a reduction in PAP that was 13.9 mm Hg larger than was seen in the placebo group.

"This is the most impressive reduction in the pulmonary arterial pressure that we've ever seen in pretreated patients with PAH," said lead author and principal investigator Marius M. Hoeper, MD. "For me, it's one of the strongest signals suggesting that we truly achieved some regression of the disease's adverse changes in the pulmonary vessels. However, this remains a hypothesis that we need to explore in future studies."

Adverse events led to discontinuation of sotatercept in 1.8% of patients, compared with 6.2% in the control arm. Nosebleed, telangiectasia and dizziness were more common with sotatercept than placebo.

Sotatercept has been granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation and Orphan Drug designation by the FDA, as well as Priority Medicines designation and Orphan Drug designation by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of PAH.

As noted in an editorial comment by Darren B. Taichman, MD, PhD, and colleagues, accompanying the NEJM publication, more study is needed to understand whether these findings, attained in a stable population of PAH, will be replicated in a sicker, less stable population, and in PAH subtypes not well represented in the study. Currently, studies are ongoing with respect to Group 2 PH patients given its efficacy in preclinical experimental PH-LHD.

This article was authored by Debra L. Beck, MSc.

References

- Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2022;43:3618-3731.

- Maron BA. Revised definition of pulmonary hypertension and approach to management: A clinical primer. J Am Heart Assoc 2023;12:e029024.

- Guazzi M, Ghio S, Adir Y. Pulmonary hypertension in HFpEF and HFrEF: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:1102-11.

- Sorajja P, Whisenant B, Hamid N, et al. Transcatheter repair for patients with tricuspid regurgitation. N Engl J Med 2023;388:1833-42.

- Hassoun PM. Pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2021;385:2361-76. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2000348

- Maron BA, Abman SH, Elliott CG, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: Diagnosis, treatment, and novel advances. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021;203:1472-87.

- Hoeper MM, Badesch DB, Ghofrani HA, et al. Phase 3 trial of sotatercept for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2023;388:1478-90.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Prevention, Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Lipid Metabolism, Acute Heart Failure, Pulmonary Hypertension, Hypertension

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Heart Failure, Pulmonary Veno-Occlusive Disease, Longevity, Stroke Volume, Atrial Fibrillation, Hypertension, Pulmonary, Lung Diseases, Tricuspid Valve, Sodium-Glucose Transporter 2

< Back to Listings