Focus on Heart Failure | Reimagining Solutions: The AHFTC Workforce Crisis

The burden of heart failure (HF) continues to rise in the U.S., with about 1 million new patients every year.1 About 8 million people will have HF by 2030, with an estimated cost of $70 billion annually to the health care system.2

Significant innovations in HF include new classes of medications for guideline-directed medical therapy, novel therapies for cardiac amyloidosis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and transcatheter valvular interventions.

Innovations have also occurred with improved short-term hemodynamic support devices and left ventricular assist devices (LVAD), as well as in the arena of heart transplantation (HT), including noninvasive detection of allograft rejection, utilizing hepatitis C-positive donors, and organ donation after circulatory death.

Despite these advances and the growing burden of disease, we're facing a workforce crisis. Interest has been declining in advanced HF and transplant cardiology (AHFTC) training and this is reflected in a reduction in applicants.

According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), in the 2023-2024 cycle, only 74 cardiovascular medicine fellows applied for AHFTC fellowship, filling 71 of 127 (56%) positions. Consequently, 45 of 73 (62%) programs went unmatched.3

This is against a backdrop of more than 1,100 applicants matching into cardiovascular medicine fellowship training.3

It is the responsibility of our specialty to critically engage with stakeholders, understand the reasons and factors at play, and brainstorm effective means to build a pipeline of future specialists in HF cardiology. If the current decline in the HF pipeline continues, a workforce shortage would adversely impact the care of our vulnerable patients with HF.

The Role of the HF Specialist: It's a New World

Cardiologists who specialize in HF care derive profound fulfilment from their work, in part because of the challenges that come from the heterogeneity of pathologies, and they feel the profound satisfaction that comes from developing long-lasting relationships with patients with chronic illness. This has inspired the hashtag #ChooseHF to disseminate positive experiences and reflections from members of the HF community.

As a specialty, HF offers many different opportunities for career advancement and "sub-subspecialization" because of the expanding number of roles that have become routinely expected from today's HF clinician. These include the clinical care of the HF, HT and LVAD patient; perioperative consultant for high-risk cardiac patients (severe HF, cardiomyopathy, high-risk CABG); management of patients with pulmonary hypertension as well as those with cardiogenic shock, requiring temporary mechanical circulatory support (MCS). However, this also may bring about challenges as a result of the acuity of patients, the growing workload and other career-related factors we will discuss hereafter.

Too Little Exposure, Too Little Awareness

The lack of or limited exposure of cardiology fellows to advanced HF, HT and LVADs may play a role in the lagging interest in AHFTC training. Notably, AHFTC fellowships are offered by only a small proportion of the programs that have cardiology fellowships. Thus, cardiology fellows may have no or limited exposure to AHFTC early in their training and have missed opportunities for mentorship from HF faculty.4

Despite the Core Cardiovascular Training Statement (COCATS) recommendation of eight weeks of HF training/exposure over the three years of fellowship,5 fellows report wide variation in training and COCATS does not mandate exposure to HT and/or LVAD management.6

Cardiology fellows spend less time on the advanced HF service, have limited exposure to general HF care and their exposure to HF comes later in their training when career choices have been made. Additionally, there may be a disconnect between AHFTC training and the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) certification examination which has a heavy emphasis on HT and LVADs.

Yet, the current reality is that the specialty of HF requires specialized care for multimorbid patients across a wide spectrum of disease stages beyond HT and MCS. Although the scope of practice for AHFTC has expanded, i.e., now involving cardiogenic shock, rare cardiomyopathies, cardio-obstetrics and pulmonary hypertension, the curricula for AHFTC fellowship may not reflect this.7

Of note, despite the heavy emphasis on advanced HF, LVAD and HT, the greatest demand and job prospects remain the need for general HF cardiologists. Therefore, most fellows who graduate from an LVAD/transplant fellowship never practice in the LVAD/HT arena, but instead work in general cardiology jobs or in a satellite HF clinic of major transplant centers.

As a result, they may earn less than other cardiology subspecialists despite having an extra year of training. While one could argue this makes their training obsolete, another could argue that all practicing HF specialists should have training in LVAD and HT in order to learn the optimal timing of referral and candidate selection which will be relevant even at non-LVAD, non-HT centers.

New Compensation Models Needed For HF Cardiologists?

Despite taking care of the most critically ill patients, the compensation for HF cardiologists may not be commensurate with their effort and may lead to difficulty in recruiting cardiology fellows to AHFTC.

Furthermore, it is low when compared with other subspecialties where compensation is based on the revenue value unit (RVU), a model that may not accurately capture the evaluation and management services and complexity of decision-making within HF.

It should be noted that the HF cardiologist has become the de facto consultant to the critically ill patient with advanced cardiomyopathy or cardiogenic shock – without being compensated as a critical care consultant. Furthermore, downstream revenues resulting from the evaluation by an HF cardiologist, such as procedures and imaging tests, may not be factored into the compensation.

Donor selection is a tedious and time-consuming process, time that may not be reflected in any productivity metrics. Value-based payment models and designating the HF cardiologist as the primary ICU cardiologist may lead to enhanced patient outcomes as well as enhanced compensation.8

The Path Forward: Increasing AHFTC Training

Members of the broader HF community, including the ACC and the Heart Failure Society of America, are working to try to address this issue.

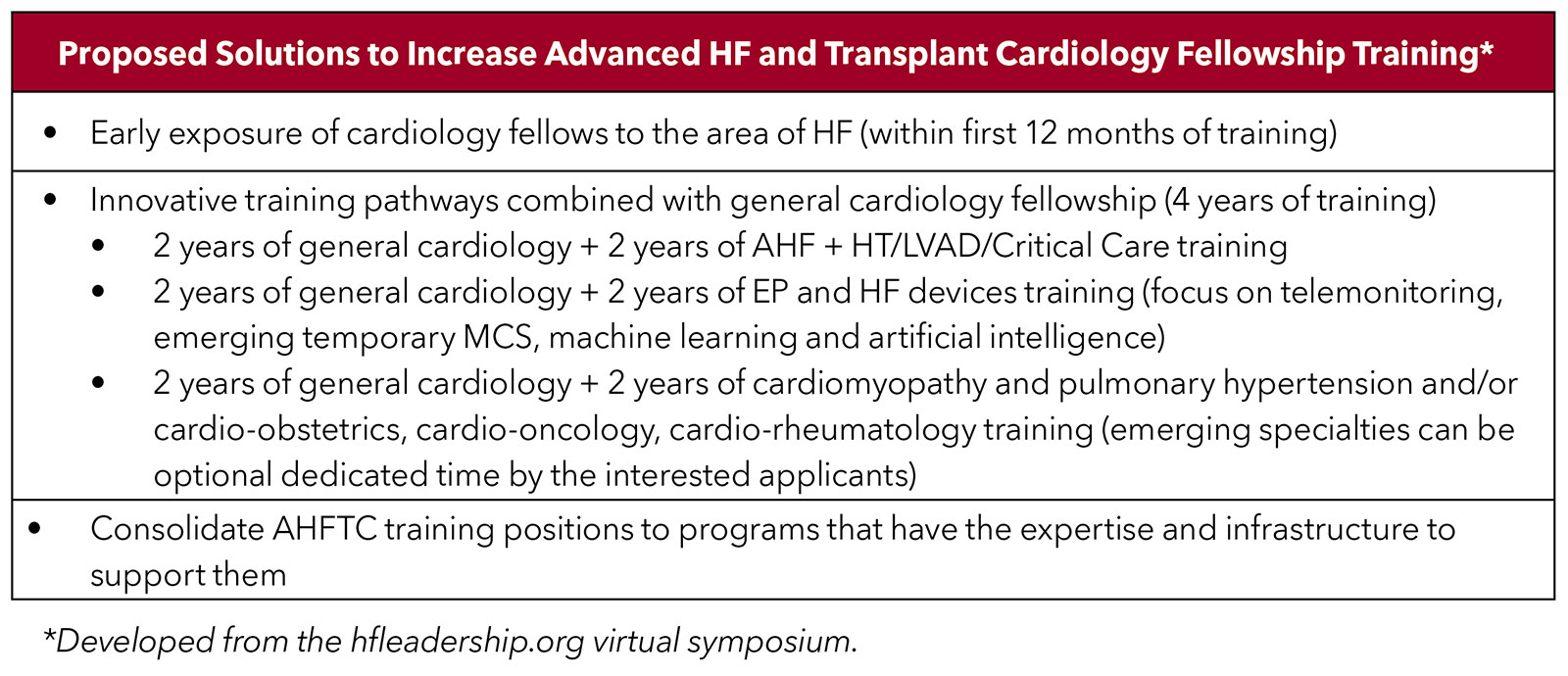

A virtual symposium held earlier this year by leaders in the field of HF brought together cardiology fellows, general cardiology and AHFTC program directors, practicing HF clinicians and employers – all with the goal of developing proposed solutions (Table) to help mitigate the crisis.

Topics of discussion included understanding of current HF program staffing and compensation models; drivers behind a fellow's decision to pursue a career in HF; and current factors impacting job satisfaction and dissatisfaction.

Organizational Efforts to Increase the Pool of HF Clinicians

In addition to downstream efforts to stimulate interest in cardiology and HF in medical school and residency programs, there are other more immediate ways that may help to increase the pool of HF physicians.

These include consideration by cardiology organizations to award diplomas in HF to internal/family medicine physicians and/or developing certification programs for advanced practice providers.

A certification program may be an option for internal medicine graduates who were unsuccessful in the cardiology match who end up in a "non-ACGME accredited fellowship in HF" who are not eligible to sit for the ABIM boards and then "are lost" to other specialties.

Furthermore, unfilled AHFTC fellowship slots could be made available to general cardiology applicants who were not successful in gaining a slot in a hybrid HF training/certification program. This would immediately improve the exposure of future cardiologists to the field of HF, and some of them may choose to pursue this as their lifetime career.

Moving Forward

Adopting the solutions offered here may reignite interest in HF training. Now, more than ever, it is important to engage general cardiology fellows and the cardiology community in pursuing a career in the field of HF.

We must ensure, in so much as we can, to continue to build a robust HF workforce to expertly combine the new innovations in HF care to manage the burgeoning HF epidemic that is expected to worsen.

Learn More, Get Involved

Read more about the workforce challenges, solutions and the work of ACC's Task Force on the CV Workforce. Click here to dive into this recent Cardiology cover story.

Find Your Home

Get involved by joining ACC's Member Sections, including dedicated sections for HF, Program Directors, Medical Directors, FITs and more. Click here to find your community.

Hone Your Skills

ACC's HF Self-Assessment Program (SAP) covers the entire field of advanced HF and transplant cardiology. It's a great resource for perfecting your knowledge of HF and completing your Maintenance of Certification requirement via ACC's Collaborative Maintenance Pathway. Click here to learn more and get started.

This article was authored by Onyedika Ilonze, MD, MPH, FACC, an Advanced Heart Failure and Transplant Cardiology specialist and assistant professor in the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, IN, and Ersilia M. DeFilippis, MD, FACC, an Advanced Heart Failure and Transplant Cardiology specialist and assistant professor of medicine, Division of Cardiology, Center for Advanced Cardiac Care, at Columbia University Irving Medical Center-New York Presbyterian Hospital. Both are members of ACC’s Heart Failure and Transplant Member Section.

References

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2022 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022;145:e153-e639.

- Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:606-19.

- The Match. National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data. Specialties Matching Service. 2022 Appointment Year. Available here.

- Chuzi S, Reza N. Cultivating interest in heart failure careers: Can we reverse the current trend? Cultivating interest in heart failure careers. J Cardiac Fail 2021;27:819-21.

- Jessup M, Ardehali R, Konstam MA, et al. COCATS 4 Task Force 12: Training in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:1866-76.

- Almufleh A, Turgeon RD, Ducharme A, et al. Proposal for an ambulatory heart failure management curriculum for cardiology residency training programs. CJC Open 2022;4:866-72.

- Blumer V, Kittleson MM, Teerlink JR, et al. A roadmap to reinvigorating training pathways focused on the care of patients with heart failure: Shifting from failure to function. J Cardiac Fail 2023;29:527-30.

- Joynt Maddox K, Bleser WK, Crook HL, et al. Advancing value-based models for heart failure: A Call to action from the value in healthcare initiative's value-based models learning collaborative. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020;13:e006483.

Clinical Topics: Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Acute Heart Failure

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Heart Failure, Hemodynamics, Amyloidosis, Allografts

< Back to Listings