Prioritizing Health | Food is Medicine: A Movement to Improve Cardiovascular Health

Cardiovascular disease has long been linked to lifestyle habits and the health and economic burden from poor diet are now staggering. Congress, federal agencies, private stakeholders, and the health care community, including cardiology, are now gearing up to tackle the problem. Food is Medicine (FIM) is a movement that is gaining traction to improve health in individuals as well as address the rising public health and economic burden from cardiovascular disease.

Impact of Poor Diet on Cardiovascular Disease

Dietary risk is now the #1 cause of mortality in the U.S. and globally, and the third leading cause of years-of-life lost or lived with disability in the U.S. Both burdens are mediated through cardiovascular and cardiometabolic diseases.

Indeed, two recent studies have helped to quantify the burden of a poor diet. A suboptimal dietary intake was responsible for 45.4% of cardiometabolic deaths in 2012 in the U.S., according to a comparative risk modeling study led by Tufts researchers,1 including cardiologist Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, FACC, former dean of the Friedman Tufts School of Nutrition Science and Policy, director of the Tufts University Food is Medicine Institute, as well as member of the ACC Nutrition Work Group.

A similar estimate was found by another modeling study, led by the Global Burden of Disease Diet Collaborators, with 48.4% of deaths from cardiovascular disease in 2017 due to dietary factors.2

Although both analyses showed small improvements over time, the economic burden has become massive: 85% of health care dollars spent in the U.S. now are for treating chronic diseases linked to poor diet, costing an estimated $1 trillion annually.3

Diets high in sodium is the biggest contributor to risk for cardiovascular disease, according to both analyses, followed by a mix of high intakes of processed meats and sugary beverages and low intakes of nuts and seeds, seafood, vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and polyunsaturated fats to replace saturated fats.

This type of dietary pattern, low in vasculoprotective phytonutrients, fiber and healthy fatty acids, and high in nutrient-poor ultra-processed foods, negatively impacts numerous physiological pathways linked to cardiovascular disease, including systemic inflammation.4

In contrast, the Mediterranean diet, DASH diet, and whole foods-plant-based diets high in beneficial food components and low in nutrients of concern are associated with reductions in cardiovascular risk that rival those of some pharmacotherapies.5 This is evidence that healthy diets should be viewed as medicine.

Disparities in Diet, Food Access

Prioritizing FIM at ACC

The ACC recently established a Board of Governors (BOG) Work Group on FIM, under the leadership of BOG chair Nicole L. Lohr, MD, PhD, FACC. The 15-member Work Group is developing resources for chapter governors and members, including education, implementation, research and advocacy guidance.

The ACC Nutrition Work Group, part of the Prevention section, also will drive education and advocacy efforts related to FIM.

Unfortunately, dietary risk is not distributed equally in the U.S. or within most countries. Negative social determinants of health, including lower socioeconomic status, are highly linked to food insecurity, defined as insufficient food or calories to maintain health, which affects 10% of U.S. households.

Recent data have documented that a large proportion of patients with cardiovascular disease in the U.S. are in fact food insecure. The prevalence of food insecurity was found to be higher among those with, vs. without, cardiovascular disease across racial groups, and to have increased from 1999 to 2018 in a study analyzing NHANES data,6 that was led by Eric J. Brandt, MD, FACC, co-chair of the ACC Disparities in Care Work Group and member of the ACC Nutrition Work Group.

Eliminating food insecurity has been the work of federal nutrition assistance programs for decades. However, this goal is no longer viewed as sufficient for advancing health equity. Diet quality also must improve. A new metric – nutrition security – is defined as "consistent access, availability and affordability of foods and beverages that promote well-being, prevent disease and, if needed, treat disease."

Moving all Americans towards this goal, especially those with chronic disease and low socioeconomic status, is the new mission of some key federal agencies and the FIM movement.

What is Food is Medicine?

An overview of the FIM movement in the U.S. was presented at the World Congress of Non-Communicable Diseases in Toronto, Canada, in August, by Kris Vijay, MD, MS, FACC, a member of the ACC Disparities in Care Work Group.

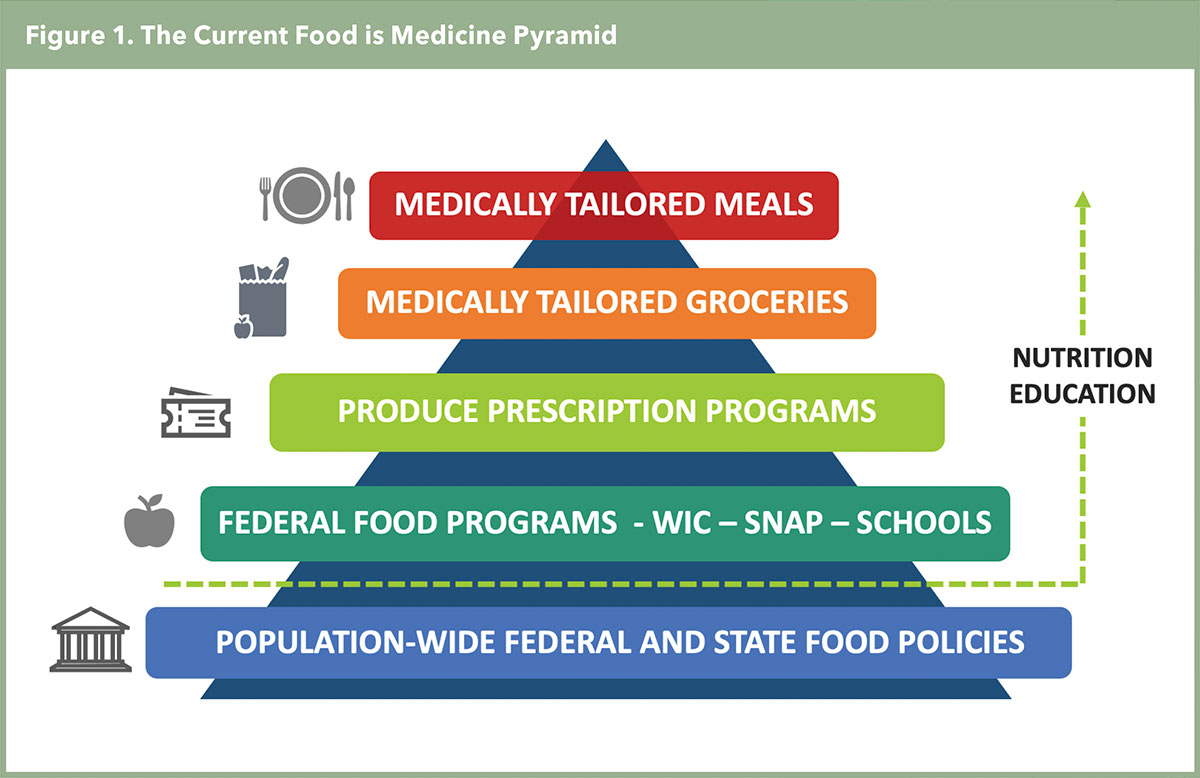

FIM is defined as "a broad initiative that aims to integrate specific food and nutrition interventions within health systems to prevent, manage and ameliorate chronic disease." The focus is ensuring that individuals with or at risk of chronic disease who have barriers to healthy eating receive a diet intervention that improves nutrition security. The level of the intervention is matched to the patient's level of dietary need and risk, as illustrated in the FIM pyramid (Figure 1).7

The medically tailored meals (MTMs) intervention is designed for patients at highest risk with complex chronic conditions (e.g., severe heart failure). MTMs typically include 10 plant-forward meals per week that are usually scratch-made and devoid of processed foods, added sugar and sodium and delivered for a specified number of weeks, along with education and recipes. Notably, this strategy is different from nutrition interventions like vitamins, elemental supplementation or medical foods.

The medically-tailored groceries intervention is for those with chronic disease who can prepare meals but have financial barriers to buying healthy foods. And produce-prescription programs are typically for low-income seniors and others with health risks to provide vouchers for fruits and vegetables that are redeemable at farmer's markets and grocery stores. Importantly, these FIM interventions rise above existing federal programs aimed at combating food insecurity, like SNAP benefits and WIC, to improve nutrition security.

Of note, growing evidence suggests some FIM interventions reduce emergency department visits, hospitalizations, nursing home stays as well as costs, while others reduce intermediate outcomes. Modeling studies estimate an $11 billion net savings a year in health costs in the U.S., if all eligible individuals were provided MTMs, and a $40 billion net savings if a produce prescription program was used by all eligible individuals. Yet real world data are needed.

Implementing FIM in Health Systems

Figure 2. Current Legislative Efforts For FIM

Federal

Medically Tailored Meals (MTMs) Demonstration Program Bill (S. 2133)

Bipartisan bill would fund MTMs under Medicare Part A in a four-year Pilot Program for beneficiaries with a 'diet-impacted disease' with the goal of demonstrating reduced hospitalizations.

SNAP Nutrition Security Bill (S.2326, H.R. 4909)

Bipartisan/Bi-cameral effort would modify SNAP (the largest federal food safety net program) to incorporate nutrition security as a program metric.

Medical Nutrition Education (House Resolution) (HR 784)

Bipartisan House Resolution has passed that calls for activities and policies that ensure expanded health professional nutrition education.

States

Medicaid Waivers for Nutrition Support

Section 1115 Waivers allow states to provide access to nutrition support for Medicaid beneficiaries, including Food is Medicine interventions. CA, MA, NJ, NC, OR, DE, NM, NY and WA have received or applied for CMS approval for Section 1115 waivers. Medicaid officials may also grant Medicaid Managed Care plans access to FIM services via new "in lieu of services" (ILOS) authority. CA has used Section 1115 and ILOS authority to allow its managed care plans to cover 14 categories of community support including FIM services.

Retail SNAP Incentive Program

Provides additional 'bonus dollars' to recipients when SNAP benefits are used to purchase fruits and vegetables not only at farmer's markets but in retail settings.

The U.S. health system is better positioned to integrate FIM services today than a decade ago. A number of factors support expansion of FIM, including greater numbers of insured individuals, the transition to population health management and value-based team-care, more robust diet evidence along with information systems for assessment and screening, and a growing focus on health equity.

Most health systems have the basic elements to develop care pathways for FIM, including electronic health record prompts for screening for food or nutrition insecurity, and multidisciplinary care teams with social workers and registered dietitian nutritionists for referrals. Examples for these care pathways are emerging, including from a recent American Heart Association (AHA) Presidential Advisory.8

Key to success is partnerships with local community-based organization(s) (CBOs) that supply MTMs. The Food is Medicine Coalition is one resource for finding such resources across the U.S. (fimcoalition.org).

Funding is the major current limitation. Some CBOs offer grants, and some organizations such as the AHA and the Rockefeller Foundation will start funding research proposals for FIM implementation trials aimed at identifying the best models and solutions. Several federal and state legislative efforts are also underway to expand funding for these interventions (Figure 2).

Finally, better physician knowledge and competencies related to nutrition will be essential to delivering FIM services. Only a small proportion of medical schools provide the recommended hours of nutrition education, and graduate medical education programs offer even less, a gap the ACGME is working to close. This will be important, including for cardiologists.

In an ACC CardioSurve survey fielded in 2017 by ACC Nutrition Work Goup member Stephen Devries, MD, FACC, most respondents could not recall receiving a nutrition lecture during cardiovascular fellowship, leaving them with low competency for diet assessment and counseling.9

This article was authored by Karen E. Aspry, MD, MS, FACC, chair of the ACC Nutrition Work Group and the BOG FIM Work Group, and governor of the ACC Rhode Island Chapter, and Furrukh S. Malik, MBBS, FACC, co-chair of the BOG FIM Work Group and governor-elect of the ACC Tennessee Chapter.

References

- Micha R, Penalvo JL, Cudhea F, et al. Association between dietary factors and mortality from heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes in the United States. JAMA 2017;317:912-24.

- GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019;393:1958-72.

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;147:e93-e621.

- Mozaffarian D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: A comprehensive review. Circulation 2016;133:187-225.

- Aggarwal M, Ornish D, Josephson R, et al. Closing gaps in lifestyle adherence for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2021;145:1-11.

- Brandt EJ, Chang T, Leung C, et al. Food insecurity among individuals with cardiovascular disease and cardiometabolic risk factors across race and ethnicity in 1999-2018. JAMA Cardiol 2022;7:1218-26.

- Mozaffarian D, Blanck HM, Garfield KM, et al. A food is medicine approach to achieve nutrition security and improve health. Nat Med 2022;28:2238-40.

- Volpp KG, Berkowitz SA, Sharma SV, et al. Food Is medicine: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;Sept 28:[Epublished ahead of print].

- Devries S, Agatston A, Aggarwal M, et al. A deficiency of nutrition education and practice in cardiology. Am J Med 2017;130:1298-1305.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Prevention, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, Diet

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Secondary Prevention, Sports, Diet, Healthy, Cardiovascular Diseases, Chronic Disease

< Back to Listings