Cover Story | Gearing Up For Back to School: The Basics of Sports Cardiology

Sudden cardiac death of a young athlete is a rare but emotionally devastating event. Each one receives extensive media attention and leaves a lasting impact on the wider community. These deaths are usually attributed to sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) related to hereditary, structural or electrical abnormalities affecting the heart. The desire to protect young athletes from risk of sudden death is a public health priority.

As "Back to School" season approaches, more cardiologists will see young adults referred for specialty care because screening has detected a potential issue. Others will perhaps be asked to conduct pre-participation screenings for school sports. Are you prepared to assess these individuals? Do you feel confident to make recommendations regarding participation?

This month, Cardiology explores these questions and reviews what is undisputed: that the best way to protect athletes (and others) from sudden cardiac death during sports is an emergency action plan and better access to automated external defibrillators (AEDs).

Pre-participation Screening: Who, When, Why, How?

The purpose of pre-participation screening is to identify conditions that may put the athlete at unreasonable risk of injury or death, and to potentially modify or reduce this risk.

Most states require children to be screened before participation in school sports, usually starting in high school but sometimes in junior high. However, the pre-participation examination (PPE) process grossly lacks standardization.

"In some states you need a doctor to do the history and physical (H&P), but others allow, for example, a chiropractor," says Matthew W. Martinez, MD, FACC, co-director of ACC's Care of the Athletic Heart Live Course, held in late June at Heart House in Washington, DC.

"There are also significant data suggesting the H&P, as it is often conducted, is not sufficient to identify all potential risk, especially cardiac risk," says Martinez who serves as cardiologist for Major League Soccer.

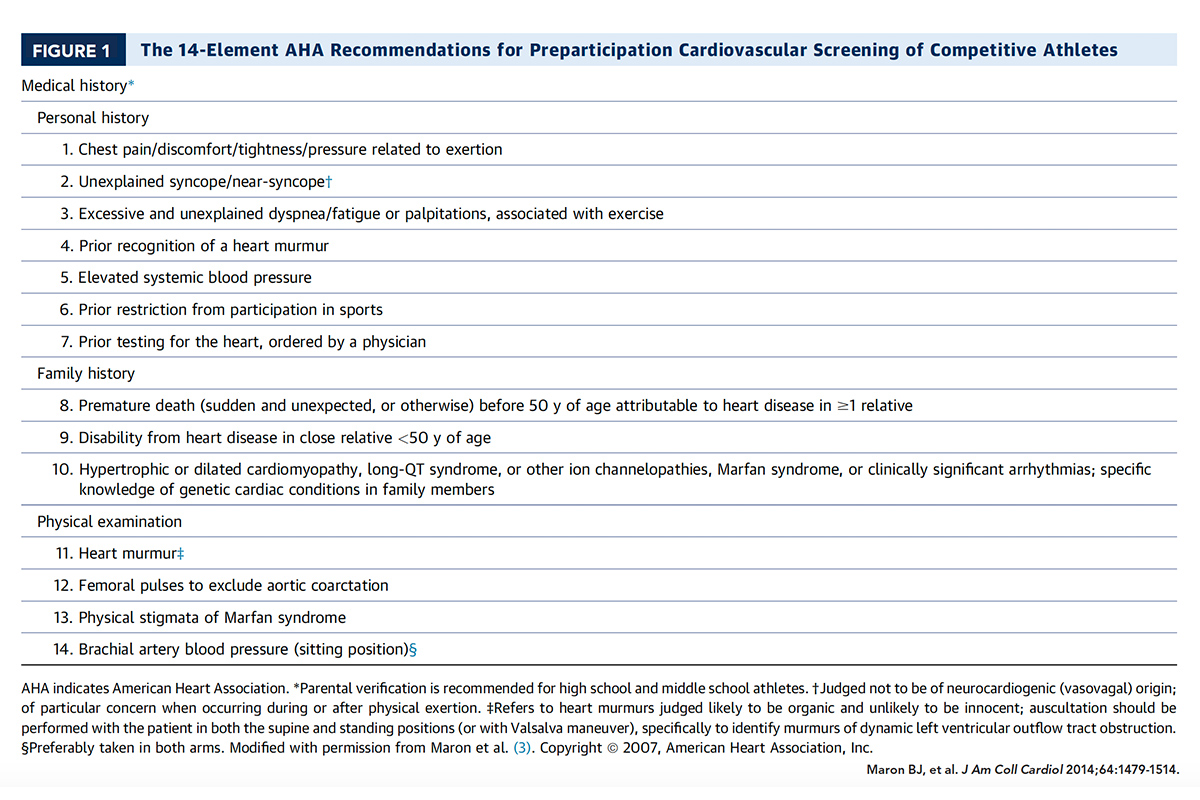

To improve the sensitivity of the personal and family history and physician examination, the ACC and American Heart Association (AHA) developed a 14-element pre-participation screening tool (Figure 1).

Kimberly G. Harmon, MD, a family physician who specializes in sports medicine, has some particular issues with the H&P. "Knowing that someone passed out while exercising is really important information. But one of the questions on the questionnaire asks about a family history of heart conditions, including hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy, long-QT syndrome, or other ion channelopathies, Marfan syndrome, or clinically significant arrhythmias. And the kid is like, 'well I know Grandpa had something with his heart, he has a pacemaker.'"

"This just creates a mess because now this kid might have a relative with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and they need a full workup, but more likely this is a false-positive," says Harmon, who is also head football physician for the University of Washington Huskies.

In a recent study in which Harmon participated, of 3,620 student athletes, 1,642 or 45.4 percent, marked at least one positive history response on the questionnaire.1 After review by a physician, 50.4 percent of these were deemed not clinically concerning for cardiac disease. The rest were considered to have a positive history questionnaire warranting further evaluation.

Partly in response to this potential for confusion, but for other reasons too, the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians and American College of Sports Medicine have suggested that the PPE be done, not in a large-scale, school-based environment, but rather in the medical home.2

"We're moving towards saying a sports physical should be done in the student's medical home as part of their well child care, and not as one of those gym-based screenings. One of the most important parts of a PPE that we do right now is having the sex, drugs and rock-and-roll conversation with kids, and making sure their immunizations are up-to-date, and that's better done in their medical home," says Harmon.

Indeed, the PPE is estimated to represent the sole source of medical evaluation for between 30 percent and 88 percent of school-aged children.3 With that, however, she notes that one reason to do large-scale, school- or community-based screenings is because requiring an exam by a family physician has been identified as a barrier to participation in sports.

Once the collegiate level is reached, things are more regulated. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) currently requires every student-athlete to undergo a PPE conducted by a licensed medical doctor or doctor of osteopathic medicine. They do not require an electrocardiogram, although many schools routinely use them, especially for basketball players.

The 12-lead ECG

Sports cardiologists throw down their gloves when it comes to the use of a resting electrocardiogram (ECG) in pre-participation screening. The issue is whether the ECG offers sufficient sensitivity and specificity for screening of young athletes and can be properly interpreted when used as a large-scale screening tool.

Guidelines around the world reflect the lack of consensus: ACC/AHA guidelines do not recommend routine use of ECG in PPE. European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines do. A recent joint position statement from the Canadian cardiology societies splits the difference and recommends a tiered approach.

The NCAA does not require an ECG to participate in intercollegiate sports, but virtually all professional sports organizations (NHL, NFL, FIFA, Premier League) do, as does the International Olympic Committee.

In an editorial, Barry J. Maron, MD, MACC, one of the authors of the ACC/AHA guidelines on this topic, and coauthors, say the College's opposition to broad-based screening that relies on the 12-lead ECG is based on "unacceptable numbers of false positives that overwhelm the screening system with expensive downstream noninvasive testing; false negatives that defeat the very reason for such screening initiatives; logistical challenges in reliably interpreting ECGs in large populations (e.g., for QT-interval duration); overall cost burden; and, finally, the failure to demonstrate that ECG screening reduces cardiovascular mortality."4

For her part, Harmon would argue that the false-positive rate with the H&P is higher than with ECG, but agrees that neither has been shown to reduce mortality.

Evidence in support of using ECGs for athlete screening comes mostly from a large prospective Italian study that followed 42,386 competitive athletes aged 12 to 25 years. Over a 26-year follow-up, the researchers saw an 89 percent decrease in SCA incidence with mandatory screening including ECG, primarily attributed to a decrease in sudden death due to cardiomyopathy.

A more recent study looked at 11,168 adolescent athletes (mean age 16.4 years) in the English Football Associations mandatory cardiac screening program.5 The researchers found that 830 (7 percent) athletes were referred for further investigation after preliminary H&P, plus ECG and echocardiography. Of these only 42 athletes (0.38 percent) were found to have cardiac disorders associated with SCA, including Wolff-Parkinson-White in 26 individuals. Most were treated and returned to play. Of note, the ECGs in this study were read by experts in the field.

During a mean follow-up of 10.6 years, there were 23 deaths, of which eight (35 percent) were sudden deaths attributed to cardiac causes. But here's the rub: while cardiomyopathy accounted for seven of eight deaths, only two of these eight had abnormal cardiac screening results. Both had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and were advised to avoid competitive sport. One died one year after screening and the other died 11.5 years after screening.

The researchers noted that screening once during late adolescence may fail to detect a number of athletes who will subsequently have a cardiomyopathy.

"This is the most comprehensive study to date for athlete screening," says Martinez. "Despite that, not all players at risk were identified, so much more is needed before determining that the ECG solves or even improves the screening process. This includes do you have a plan to handle those not identified and those not identifiable by screening (e.g., commotio cordis)? Do you have a plan to handle the positive findings in a timely manner and are you expert enough to determine the findings and what to do next? Otherwise, we end up eliminating many athletes for findings that may or may not have had any impact on their lives at all."

Those on both sides of the argument agree that much of the issue revolves around the logistic complexities of performing and interpreting the test, particularly for large numbers of student athletes. False-negatives are high with ECG screening in part because the athlete's heart differs in ways that many cardiologists may not be familiar with, making them unqualified to interpret the test (see sidebar).

"I think one of the most critical factors [in using ECGs in screening], because of false-positives, is to resource out and find qualified people," said Ron Courson, ATC, PT, in a talk on the topic at the live course at Heart House.

Courson, who is the director of sports medicine with the University of Georgia Athletic Association, stressed not just having the ECGs read by a qualified sports cardiologist, but also using good equipment and well-trained technicians so the data gathered are of high quality.

"The issues arise when something looks a little funny and the doctor decides to overcall it, but then that athlete has to go and figure out what to do next. They may not be able to get into a cardiologist for weeks and finding a pediatric cardiologist may take even longer," says Martinez.

"Also, we've never been able to prove that we can improve an outcome by screening and identifying, say, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or the presence of an abnormal ECG," adds Martinez.

That said, pre-participation screening gives options, notes. Martinez, and allows for shared decision-making.

"If you have a test and find out you are at risk for a cardiac event, or that you have an increased risk for another condition such as breast cancer, it doesn't mean that you must immediately do something. It means that you get to decide what and how to proceed," he says.

Again, no studies have shown that screening, with or without ECG, clearly saves lives. And it's likely no study ever will. The incidence of SCD in young athletes is somewhere between one in 50,000 to one in 80,000 athletes per year, so a prospective randomized study with adequate power will probably never be done to answer the question.6

A Team Cheer for Emergency Action Plans (EAPs)

"Things are going to happen and we have to be prepared when they do," said Courson in a talk he gave on EAPs at the Care of the Athletic Heart course. Besides being an athletic trainer for multiple U.S. Olympic teams and the author of a book called Athletic Training Emergency Care, Courson is an emergency medical technician (EMT).

"I've been involved in a lot of different situations, including multiple cardiac arrests. When you have a situation, panic can ensue. But as medical professionals we have to dictate and set the tone and we have to be calm," said Courson.

How to ensure that calm? Have an EAP. Design it, teach it and rehearse it regularly. "There is no budget impact, it's simply preparation, but advanced planning makes a difference," he said.

A big difference as it turns out. In a study published earlier this year, Jonathan Drezner, MD, and colleagues identified 132 cases of exercise-related SCA over a two-year period.7 Mean patient age was 16 years (range, 11-27 years) and 84 percent were male.

The majority of cases (93 percent) were witnessed. While overall survival was 48 percent, if an athletic trainer was involved in the resuscitation, survival jumped up to 83 percent. If an on-site AED was used, survival was 89 percent.

ECG Interpretation for the Young Athlete

"Whether you do ECG for pre-participation screening or not, you have a good chance of having someone roll into your office with an ECG they had done by a screening program. So you'll need to know how to interpret it, or know that you don't know how to interpret it," says Martinez.

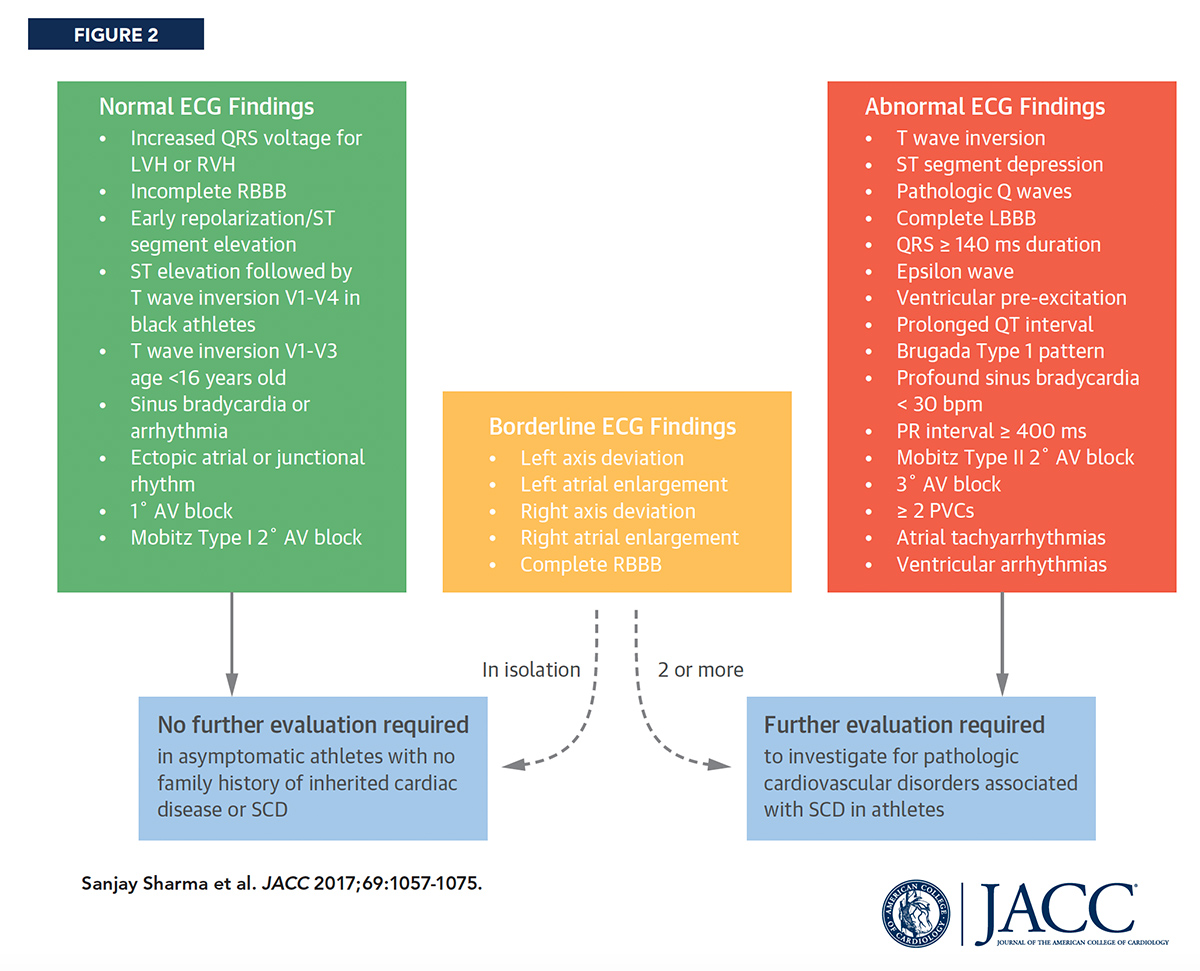

Sanjay Sharma, MD, one of the field's leading experts, gave a comprehensive talk on ECG interpretation at ACC's Care of the Athletic Heart course. He outlined ECG findings that should be investigated further and those that may appear alarming, but actually represent physiological cardiac adaptation to regular exercise.

Broadly speaking, said Sharma, regular and long-term participation in intensive exercise, which has been defined as a minimum of four hours per week, is associated with electrical manifestations that can be categorized into two groups: those reflective of increased vagal tone and those reflective of enlarged chamber size.

Physiological arrhythmias in athletes associated with increased vagal tone include bradycardia, sinus arrhythmia, first degree atrio-ventricular block, ST-elevation, and tall T waves. Left ventricular hypertrophy, incomplete right bundle branch block and left atrial enlargement are also commonly seen in young athletes and do not require further investigation (Figure 2).

The trick, he suggested, is to be able to spot those athletes who "actually develop repolarization changes that overlap with diseases implicated in sudden cardiac death [because] in these situations, clearly, an erroneous diagnosis has very serious consequences." His comments were a review of international recommendations for ECG interpretation in athletes published in 2017, for which he served as lead author.10

Interestingly, in a separate talk on women athletes, Meagan M. Wasfy, MD, FACC, noted that women have different prevalences of normal training-related ECG changes and abnormal pathological findings.

For example, in a study of competitive rowers, women were significantly less likely than men to have isolated voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy and early repolarization pattern. Women athletes also have "consistently and disproportionally lower" rates of SCA and sudden death, she said.

"It...speaks to the role of targeted first responders," said Courson. "You need to train your staff. Even if they aren't doing the resuscitation, they can still have a role in scene control, retrieving equipment and helping to activate the EAP."

Just recently, the NCAA passed legislation mandating that every institution have an EAP customized for each venue. The plan should pay particular attention to the management of cardiac arrest and the use of AEDs, but should also consider emergency action for other nontraumatic injuries (e.g., exertional heat emergencies, stroke, asthma, exertional collapse associated with sickle cell trait, all exertional and nonexertional collapses, and mental health emergencies).

The "medical time-out" is additive to an EAP and involves a short pre-event meeting for first responders.

"Why do we call a time-out in a basketball game? So we can organize and call the right play… the medical time-out is the same idea," said Courson. It's an opportunity to check what medical staff are present, meet the visiting staff and assess potential issues that might arise. "Are there weather considerations, traffic flow considerations? It's just about taking a few minutes to work these things out in advance."

"If I had an emergency in my house today and I called 911 EMS dispatch, a red light comes on and they know exactly where to go to my address. If I called 911 and tell them I have an emergency in my coliseum with a basketball player, there are 60 outside entrances on four different levels…what entrance do you direct the ambulance to, who is going to open it…these are things that need to be worked out ahead of time."

To drive the point home that AEDs need to be available – and with their batteries charged – Courson related a story of a high school athlete who suffered an SCA but the school's newly-purchased AED was locked in the principal's office. The athlete died. It's estimated that one in five out-of-hospital cardiac arrests occur near an inaccessible AED.8

The emergency plan is also about spectators. Of the four cardiac arrests during athletic events that Courson has attended in his 30 years as an EMT, none involved an athlete. "I've had an SEC football official in a game, a coach, a visiting coach, and an administrator for the Olympics [who collapsed in the in-field] during the opening ceremony of the '96 Olympics in Atlanta."

Here too, fortune appears to favor the prepared. In a two-year prospective study of SCA in 2,149 U.S. high schools, 33 of the 59 confirmed events (56 percent) occurred in adults and the remainder in students.9 Not all occurred at an athletic facility or during training or competition, but of the 18 student-athletes and nine adults who arrested during physical activity, 89 percent survived to hospital discharge.

"We all agree that no screening process will ever be perfect so the single best way to make sure that you are caring for your athletes, and others, is to have an Emergency Action Plan and ready access to an AED," says Martinez.

References

- Williams EA, Pelto HF, Toresdahl BG, et al. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8(14).e012235.

- Korioth T. Updated monograph offers new guidance on preparticipation physical evaluation. AAP News. 2019 Jun 26; Available here.

- Conley KM, Bolin DJ, Carek PJ, et al. J Athl Train 2014;49:102-20.

- Maron BJ, Thompson PD, Maron MS. J Am Heart Assoc 2019 Jul 16;8:e013007.

- Malhotra A, Dhutia H, Finocchiaro G, et al. N Engl J Med 2018;379:524-34.

- La Gerche A, Baggish A, Heidbuchel H, et al. Heart Lung Circ 2018;27:1116-20.

- Drezner JA, Peterson DF, Siebert DM, et al. Sports Health 2019;11:91-89.

- Sun CL, Demirtas D, Brooks SC, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:836-45.

- Drezner JA, Toresdahl BG, Rao AL, et al. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:1179-83.

- Sharma S, Drezner JA, Baggish A, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1057-75.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Care Team, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Noninvasive Imaging, Prevention, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, Implantable Devices, EP Basic Science, Genetic Arrhythmic Conditions, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Aortic Surgery, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and CHD and Pediatrics, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Arrhythmias, CHD and Pediatrics and Imaging, CHD and Pediatrics and Prevention, CHD and Pediatrics and Quality Improvement, Echocardiography/Ultrasound, Exercise, Sports and Exercise and Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Sports and Exercise and Imaging

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, American Heart Association, Ambulances, Arrhythmia, Sinus, Asthma, Atrial Fibrillation, Athletes, Bradycardia, Breast Neoplasms, Bundle-Branch Block, Cardiomyopathies, Cardiomyopathy, Dilated, Cardiomyopathy, Hypertrophic, Child Care, Commotio Cordis, Consensus, Death, Sudden, Death, Sudden, Cardiac, Channelopathies, Defibrillators, Echocardiography, Electrocardiography, Emergency Medical Technicians, Emergencies, Follow-Up Studies, Exercise, Health Priorities, Hot Temperature, Hypertrophy, Left Ventricular, Incidence, Long QT Syndrome, Immunization, Mandatory Testing, Marfan Syndrome, Osteopathic Medicine, Medical Staff, Mental Health, Pacemaker, Artificial, Patient-Centered Care, Parkinson Disease, Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest, Pediatrics, Physicians, Family, Prospective Studies, Prevalence, Sickle Cell Trait, Stroke, Sports Medicine, Students

< Back to Listings