Outcomes of Physiologic vs. Anatomical Repair and Strategies For Left Ventricular Retraining in Congenitally Corrected Transposition of the Great Arteries

Quick Takes

- Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries can be managed with physiologic or anatomical repair strategies; long-term outcomes between these strategies are still debated.

- Recent meta-analyses comparing these two management strategies have shown improved survival in patients undergoing anatomical repair, although left ventricular (LV) dysfunction can still occur.

- Further study to optimize LV retraining to prevent LV dysfunction post anatomical repair is warranted.

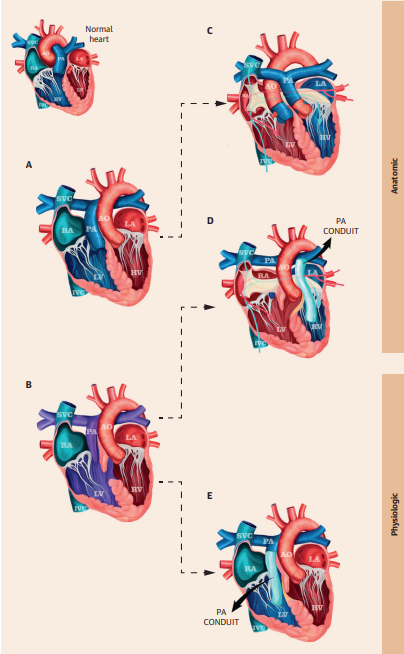

Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (ccTGA) is defined by atrioventricular and ventricular-arterial discordance and is often associated with additional lesions, most commonly ventricular septal defect, pulmonary valve stenosis, and tricuspid valve abnormalities, as well as progressive atrioventricular block. Its rarity and inherent heterogeneity along with its various management pathways make predicting long-term outcomes difficult (Figure 1). Unrepaired patients or those who undergo physiologic repair often develop systemic right ventricular (RV) failure by the fifth decade of life, and those with associated lesions can fail sooner.1 Thus, there is growing interest to recommend anatomical repair when possible because, once ventricular function deteriorates, patients often require advanced heart failure (HF) therapies, such as mechanical support and transplant.

Figure 1: Physiologic and Anatomical Repair in ccTGA

Reprinted with permission from Jacob et al.2

Two phenotypes of ccTGA in levocardia with different repair techniques. The drawing on the top left represents a normal heart. (Panel A) ccTGA. (Panel B) ccTGA with VSD and PS. (Panel C) Double switch operation. (Panel D) Rastelli-Mustard operation with VSD closure. (Panel E) LV-PA conduit with VSD closure.

AO = aorta; ccTGA = congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries; IVC = inferior vena cava; LA = left atrium; LV = left ventricle; PA = pulmonary artery; PS = pulmonary stenosis; RA = right atrium; RV = right ventricle; SVC = superior vena cava; VSD = ventricular septal defect.

Early and Late Outcomes

Two recent meta-analyses have now provided the largest sample sizes to date for comparison between these management strategies. The first meta-analysis, which included 535 patients with physiologic repair and 1,322 patients with anatomical repair, including atrial-arterial switch and atrial switch–Rastelli, reported the composite outcome of all-cause death or transplant in the immediate postoperative period through 10 years postoperatively. There was similar operative and in-hospital mortality but less postdischarge mortality (9.7 % vs. 6.1%), lower reoperation rates (20.6% vs. 17.9%), and less ventricular dysfunction (43% vs. 16%) in the anatomical repair group.2 The second meta-analysis included 1,222 patients with physiologic repair and 1,622 patients with anatomical repair, including atrial-arterial switch and atrial switch–ventricular operations and excluding those who underwent transplant. The investigators compared mortality and reoperation outcomes through 20 years postoperatively, which showed a lower risk of mortality (17.4% vs. 11.7%) and reintervention at 10 years (30.3% vs. 24.5%) in the anatomical repair group.3 Whereas the first meta-analysis noted better outcomes in those with a true arterial double switch technique rather than a Rastelli double switch technique, no difference in mortality was seen in the second meta-analysis, although true arterial double switch was associated with overall lower reoperation rates. Further, this second meta-analysis demonstrated anatomical repair done prior to 5 years of age and preoperative pulmonary artery banding (PAB) were associated with increased survival.

LV Retraining and Evaluation

The most challenging decision-making regarding treatment strategy is encountered in the one-third of patients with ccTGA who have intact ventricular septums. In these cases, the subpulmonary morphologic left ventricle (mLV) undergoes rapid deconditioning as the pulmonary vascular resistance falls postnatally, and thus PAB to pressure load the mLV prior to pursuing anatomical repair is required.4,5 Most patients (>90%) can be successfully retrained with this pressure loading and are referred for a double switch procedure if performed early.5,6 Although anatomical repair for these patients is still associated with improved survival compared with those who undergo physiologic management, long-term left ventricular (LV) reserve following anatomical repair is not fully known, and mLV retraining is associated with higher rates of death, transplant, and moderate-to-severe LV dysfunction than in those who did not require retraining.6

A proposed mechanism for acquired LV dysfunction was reported in a recent study examining histopathologic specimens of myocardium following PAB. The myocardium demonstrated myocyte hypertrophy without compensatory increase in capillary density in patients with ccTGA following PAB.7 This pathologic adaptation to pressure load may be especially relevant when considering late PAB or late anatomical repair. Mature myocardium remodels differently from neonatal myocardium, which adapts not only with myocyte hypertrophy but also hyperplasia and increases in capillary density in response to acute pressure load. Another study demonstrated excessive, and likely pathologic, increases in LV mass relative to LV pressure following PAB in patients who failed LV retraining, all of whom were enrolled at >4 years of age.4

One described technique to mitigate LV dysfunction is the use of serial PABs, during which the initial PAB is tightened with a series of clips to either systemic pressures or until the LV demonstrates, through intraoperative monitoring, an increase in size, decrease in function, or worsening mitral regurgitation (MR) or arrhythmias. Patients are reassessed in 6-9 months using echocardiography, cardiac catheterization, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) to determine serial PAB tightening or candidacy for the double switch procedure. This strategy is employed to avoid pathologic pressure overload with excessive PAB tightening in hopes of preserving longitudinal LV function.5 Another technique for mLV retraining includes combined pressure and volume loading of the LV via PAB and creation of an atrial septal communication.8 The left-to-right shunt across the atrial communication serves as dynamic volume loading of the mLV based on the patient's activity level and metabolic needs. The atrial communication also acts as a pressure-limiting valve to minimize pressure overload of the mLV.8,9 Notably, the volume load is thought to also promote capillary growth within the myocardium.7

Following a period of mLV retraining, patients are evaluated for candidacy for the double switch operation. Current evaluation for LV readiness is imperfect, and there are no formal guidelines. LV readiness assessment is multimodal, using echocardiographic, cardiac catheterization, and cMRI data to measure LV mass and function, systemic systolic pressure, end-diastolic pressure, and degree of MR (Table 1). Recently, pressure and volume loop analysis has been proposed as an additional mode of assessment because it may help to more completely assess ventricular work.10,11 The clinical utility in predicting readiness or outcomes using such methods will need to be investigated further.

Table 1: Summary of Criteria to Assess for LV Preparedness Prior to the Double Switch Operation

|

Parameter

|

Modality

|

Value

|

| LV/RV pressure ratio | Cath | >0.9 |

| LV systolic function | Cath, Echo, cMRI | EF >50-55% |

| LVEDP | Cath | <12 mm Hg |

| MV function | Cath, Echo, cMRI | ≤ mild MR |

| LVEDVi | Echo, cMRI | 40-100 mL/m2 |

| LV mass | cMRI | >50 g/m2 (age <10 years) >65 g/m2 (age >10 years) |

Modified from Mainwaring et al.4 and Schulz et al.8

Cath = catheterization; cMRI = cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; Echo = echocardiography; EF = ejection fraction; LV = left ventricle; LVEDP = left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; LVEDVi = left ventricular end-diastolic volume index; MR = mitral regurgitation; MV = mitral valve; RV = right ventricle.

Conclusion

Although there is guarded optimism about the promise of anatomical repair for patients with ccTGA, there are few data on long-term outcomes beyond 20 years following repair. Discussion of optimal surgical management for patients with ccTGA may become even more nuanced in the future with advancements in clinicians' ability to evaluate and predict suitability and sustainability of the mLV for anatomical repair, as well as with advancement in HF management strategies for patients with systemic RVs who undergo physiologic repair.

References

- van Dissel AC, Opotowsky AR, Burchill LJ, et al. End-stage heart failure in congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries: a multicentre study. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(34):3278-3291. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad511

- Jacob KA, Hörer J, Hraska V, et al. Anatomic and physiologic repair of congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84(25):2471-2486. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2024.07.056

- Anzai I, Zhao Y, Dimagli A, et al. Outcomes after anatomic versus physiologic repair of congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2023;14(1):70-76. doi:10.1177/21501351221127894

- Mainwaring RD, Patrick WL, Arunamata A, et al. Left ventricular retraining in corrected transposition: relationship between pressure and mass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;159(6):2356-2366. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.10.053

- Mac Felmly L, Mainwaring RD, Ho DY, Arunamata A, Algaze C, Hanley FL. Results of the double switch operation in patients who previously underwent left ventricular retraining. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2024;15(3):279-286. doi:10.1177/21501351231224329

- Cui H, Hage A, Piekarski BL, et al. Management of congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries with intact ventricular septum: anatomic repair or palliative treatment?. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(7):e010154. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120.010154

- Toba S, Sanders SP, Gauvreau K, Mayer JE Jr, Carreon CK. Histopathologic changes after pulmonary artery banding for retraining of subpulmonary left ventricle. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;114(3):858-865. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.06.034

- Schulz A, Kelm M, Weixler VHM, et al. Combined pressure and volume loading for left ventricular training in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. JTCVS Open. 2024;21:239-247. Published 2024 Sep 4. doi:10.1016/j.xjon.2024.08.016

- Zartner PA, Schneider MB, Asfour B, Hraška V. Enhanced left ventricular training in corrected transposition of the great arteries by increasing the preload. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49(6):1571-1576. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezv416

- Lee KJ, Flannery K, Ma M, Ho D. Real-time pressure-volume loop assessment of left ventricular performance to evaluate suitability for repair in congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Circ Heart Fail. 2025;18(2):e012609. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.124.012609

- Gusseva M, Thatte N, Castellanos DA, et al. Biomechanical modeling combined with pressure-volume loop analysis to aid surgical planning in patients with complex congenital heart disease. Med Image Anal. 2025;101:103441. doi:10.1016/j.media.2024.103441

Clinical Topics: Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Congenital Heart Disease, Acute Heart Failure

Keywords: Congenitally Corrected Transposition of the Great Arteries, Pulmonary Artery, Heart Failure