An Adolescent With a Murmur and an Unusual ECG

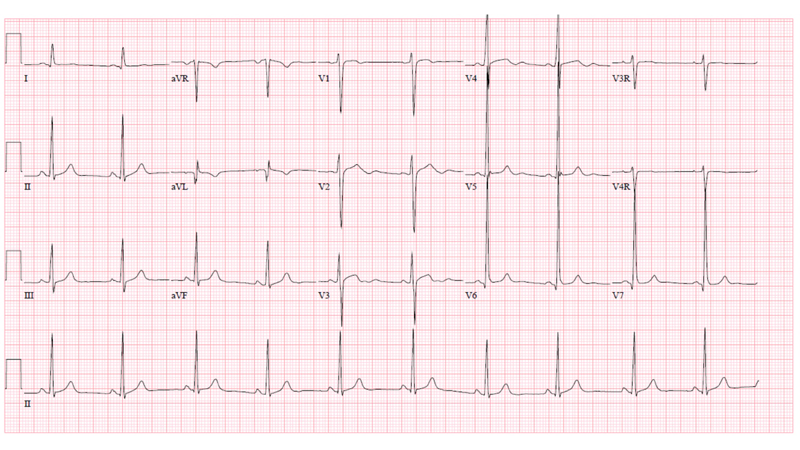

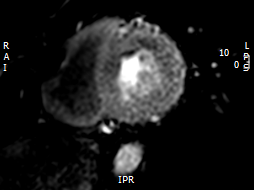

A 13-year-old male was referred to the pediatric cardiology clinic to evaluate a murmur. Review of systems was positive for sporadic chest pain during football practice, occasionally resulting in his "sitting out" during drills. His parents reported "inconsolable, incessant" crying for the entire first year of his life, attributed to "colic" that he eventually "out-grew." On exam, there was a low pitched continuous murmur heard across the precordium, greatest along the lower left sternal border. His ECG is seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

Show Answer

The correct answer is: C. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery.

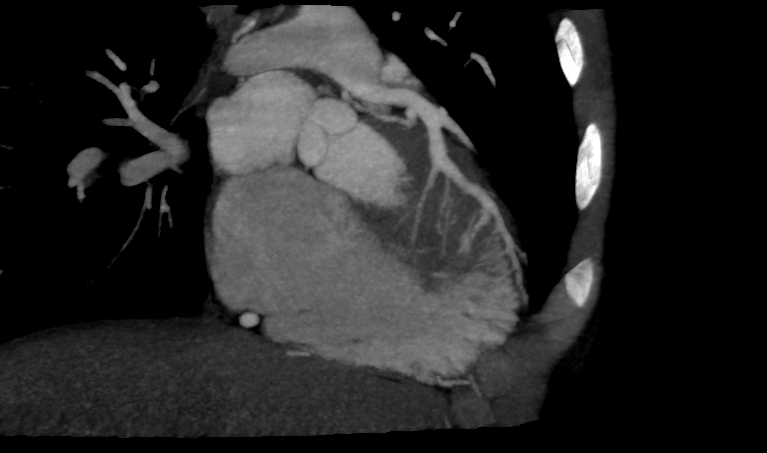

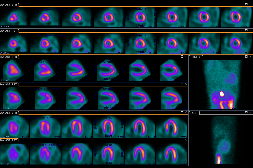

The patient's ECG is significant for an isolated pathologic Q wave in aVL, normal ST and T waves and left ventricular hypertrophy. The echocardiogram demonstrated diastolic flow from an anomalous left coronary artery into the main pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) and a markedly dilated right coronary artery with collateral flow to the left coronary artery territory (Videos 1 and 2). The left ventricular systolic function was normal with an echo-bright anterolateral papillary muscle that was felt to be consistent with a prior myocardial infarction (Video 3). There was no significant mitral valve regurgitation. The diagnosis was confirmed by CT angiography which also demonstrated a right dominant coronary system that was diffusely dilated (Figure 2). He was asymptomatic during a sestamibi treadmill stress test that revealed a reversible defect in the anteroapical wall and apex and fixed defects of the anterior and inferior walls (Figure 3), and inferolateral ST segment depression at peak exercise.

Video 1

Video 2

Video 3

Figure 2

Figure 3

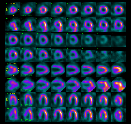

He was taken to the operating room 8 weeks following his presentation to clinic, at which time the anomalous coronary ostium was mobilized as a button from the pulmonary artery wall and translocated to the anatomic left coronary sinus of Valsalva. Warfarin was started post operatively as prophylaxis given concern for competitive flow from long standing extensive right to left collateralization. A follow-up sestamibi exercise stress test 6 months later was negative for any cardiac ischemia. The previously noted reversible perfusion defect in the anteroapical wall had resolved, while the fixed perfusion defect in the anterior and inferior walls persisted (Figure 4). Warfarin was discontinued and aspirin therapy instituted. He was cleared to participate in low to moderate static and dynamic competitive sports (Classes IA, IB, IIA and IIB). Stress CMR using regadenoson performed 2 years post-surgical repair demonstrated the area of scar from his prior infarction without any evidence of reversible perfusion defect upon provocative stress (Figure 5). The coronary artery circulation remains dilated and he has been maintained on ASA. His ECG continues to show the isolated Q wave in aVL.The patient has been cleared, following the stress CMR, for all competitive sports and has been asymptomatic. Unfortunately, anxiety related to his diagnosis and surgery has become problematic.

Figure 4

Figure 5

ALCAPA has an estimated incidence of between 1 in 30,000 and 1 in 300,000 children.1 The classic clinical presentation is that of a young infant with feeding-associated angina. As the expected physiologic post-natal decrease in pulmonary arterial pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance occurs, there is a progressive decline in left coronary perfusion pressure. Unless collateral flow from the right coronary system is extensive, myocardial ischemia with papillary muscle dysfunction or infarction, left ventricular dilation and mitral regurgitation will result. Extreme irritability is noted during feeding in infancy, as seen in this case, when myocardial oxygen demand is increased. Symptoms of congestive heart failure (tachypnea, dyspnea, diaphoresis, wheezing, failure to thrive) are often present.1,2 There is often an anterolateral infarct at the time of diagnosis and, in this situation, abnormal Q waves in leads I, aVL and precordial leads V4 to V6 will be seen on the ECG.3 Surgery should not be delayed once the anomaly is detected.

Although most patients with ALCAPA present in infancy, extensive collateralization may be protective and the diagnosis delayed until later childhood or adulthood. Collaterals from the right coronary system allow for adequate perfusion of left coronary myocardium as blood flows into the left coronary from the right and then into the pulmonary artery. In time, the left coronary will cease to perfuse its myocardial distribution, but rather becomes a conduit from the right coronary artery to the pulmonary artery, with resultant "steal" of oxygenated blood.2,4 Patients with extensive collateral coronary artery circulation will present with a continuous murmur or with sudden cardiac death later in childhood or as an adult.5 The diagnosis of ALCAPA should prompt surgery in all patients; however those with severely depressed LV systolic function and severe mitral regurgitation might be best served by heart transplantation.4

References

- Askenazi J, Nadas AS. Anomalous left coronary artery originating from the pulmonary artery. Report on 15 cases. Circulation 1975;51:976-87.

- Edwards JE. The direction of blood flow in coronary arteries arising from the pulmonary trunk. Circulation 1964;29:163-6.

- Lim DS, Matherne GP. Congenital anomalies of the coronary vessels and the aortic root. In: Allen HD, Shaddy RE, Penny DJ, Feltes TF, Cetta F, editors. Moss and Adams' heart disease in infants, children and adolescents: including the fetus and young adult. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2016.p.821-82.

- Jonas RA. Anomalies of the coronary arteries. In: Jonas RA. Comprehensive surgical management of congenital heart disease. Great Britain: Hodder Arnold;2004.p.510-24.

- Wesselhoeft H, Fawcett JS, Johnson AL. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk. Its clinical spectrum, pathology, and pathophysiology, based on a review of 140 cases with seven further cases. Circulation 1968;38:403-25.