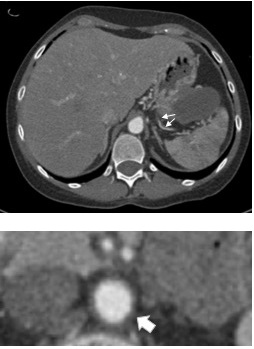

A 32-year-old woman presented with worsening lower extremity cramps and discoloration of the legs. Her history was significant for Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia diagnosed 3 years ago, initially treated with 4 cycles of dasatinib and hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin hydrochloride, and dexamethasone. Increasing BCR-ABL transcripts prompted a change to ponatinib, initially at 30 mg/d and then increased to 45 mg/d with excellent oncologic response. She eventually underwent matched unrelated donor allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Post-transplant course was complicated by acute graft-versus-host disease treated with sirolimus and prednisone. During this time frame, the patient began to develop worsening lower extremity myalgias and subsequent bluish discoloration, prompting her presentation. She underwent computed tomographic angiography (CTA) that revealed multiple bilateral lower extremity high-grade stenoses including the internal and external iliac arteries and tibial arteries (Figure 1) as well as diffuse narrowing of the splenic artery and circumferential wall thickening of the infrarenal aorta (Figure 2).

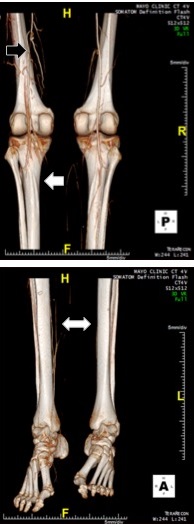

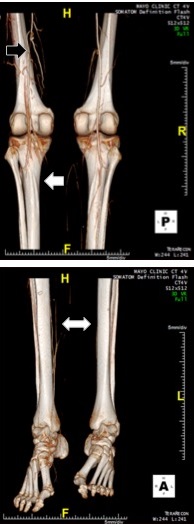

Figure 1

CTA with a three-dimensional reconstruction showing a collateralized occlusion of the left superficial artery (black arrow), poor runoff thereafter (white arrow), and poor distal circulation bilaterally (white double arrow). Reproduced with permission from Herrmann et al.10

CTA with a three-dimensional reconstruction showing a collateralized occlusion of the left superficial artery (black arrow), poor runoff thereafter (white arrow), and poor distal circulation bilaterally (white double arrow). Reproduced with permission from Herrmann et al.10

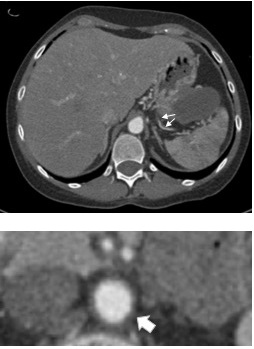

Figure 2

Abdominal CTA showing multiple stenoses of the splenic artery (arrows) and circumferential thickening of the wall of the infrarenal aorta (arrow). Reproduced with permission from Herrmann et al.10

Abdominal CTA showing multiple stenoses of the splenic artery (arrows) and circumferential thickening of the wall of the infrarenal aorta (arrow). Reproduced with permission from Herrmann et al.10

The correct answer is: D. Ponatinib

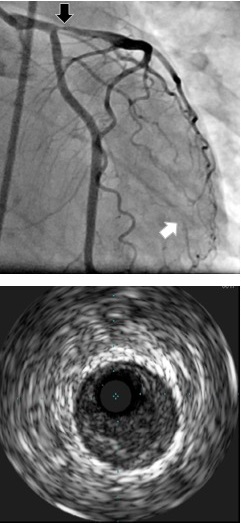

The patient underwent bilateral external iliac artery stenting, angioplasty of the left common femoral artery, and recanalization and stenting of the left superficial femoral artery. This was complicated by reperfusion compartment syndrome, requiring lower extremity compartment fasciotomy. Postoperative day 2, she developed acute chest pain, with electrocardiography revealing anteroseptal ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. On coronary angiography, diffuse vasospasm was noted as well as high-grade stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD), which was confirmed by intravascular ultrasonography (Figure 3). There was no conclusive evidence of plaque rupture or thrombus. She underwent successful bifurcation stenting of the distal left main, proximal LAD, and proximal left circumflex arteries and recovered with optimal medical therapy (aspirin, ticagrelor, carvedilol, amlodipine, and atorvastatin) without any further events and preserved left ventricular systolic function.

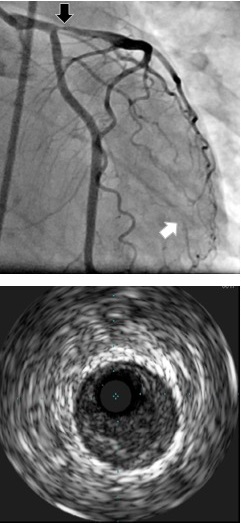

Figure 3

Coronary angiogram demonstrating high-grade proximal LAD stenosis (black arrow), confirmed as extensive soft atherosclerotic plaque on intravascular ultrasound without evidence of plaque rupture (bottom). The coronary angiogram furthermore points out occlusion of the second obtuse marginal branch with reconstitution by left-to-left collaterals (white arrows). Reproduced with permission from Herrmann et al.10

Coronary angiogram demonstrating high-grade proximal LAD stenosis (black arrow), confirmed as extensive soft atherosclerotic plaque on intravascular ultrasound without evidence of plaque rupture (bottom). The coronary angiogram furthermore points out occlusion of the second obtuse marginal branch with reconstitution by left-to-left collaterals (white arrows). Reproduced with permission from Herrmann et al.10

TKIs are the cornerstone of treatment for Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia, demonstrating substantially improved outcomes since their advent. For those patients who have failed first-generation TKIs, several newer generation therapies have been designed; these drugs are typically more potent with a potential trade-off for greater side effect profiles.1

Nilotinib and ponatinib, second- and third-generation TKIs used for the treatment of Philadelphia chromosome–positive leukemia, have been associated with rapidly progressive peripheral atherosclerosis, often termed peripheral arterial occlusive disease in the cardio-oncology literature.2-4 Coronary and visceral artery involvement has also been reported with these TKIs, often affecting multiple vessels in the same patient with an overall incidence ranging 9-48% for ponatinib.2,5,6 Although the etiology of atherosclerosis has yet to be elucidated, several mechanisms have been proposed. Impaired glucose metabolism with subsequent dyslipidemia and endothelial dysfunction may be related to inhibition of ABL.7 Other reports have implicated a direct drug effect on the vascular endothelium.8 Regardless, multiple observational studies have associated nilotinib and ponatinib therapies as being pro-atherogenic, with an increased risk noted in those with underlying cardiovascular risk factors.9 To this date, therapy is limited and often involves removing the offending agent, providing best peripheral vascular medical therapy (antiplatelet agent, statin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and amlodipine), and aggressively controlling modifiable cardiovascular risk factors.4,10

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease has not been as clearly linked to the other TKI therapies mentioned above. Imatinib, the first clinically approved multi-targeted TKI, does not appear to have the same rates of arterial thrombotic events as ponatinib and nilotinib,1-3 potentially due to the lack of vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor inhibition.2,4 Ibrutinib, a newer generation TKI, has been linked to higher rates of atrial fibrillation requiring hospitalization, although no known vascular disease has been reported to date.11 Sorafenib and sunitinib are TKI therapies used primarily for the treatment of abdominal malignancies. Both drugs inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor. Cardiotoxicities observed with sorafenib and sunitinib include hypertension, profound vasospasm, coronary artery disease, and ventricular dysfunction, with peripheral vascular disease occurring to a much lesser extent.4,11

Here we present a case of rapidly progressive atherosclerosis affecting multiple arteries in a young patient. Her extensive atherosclerotic disease was attributed to ponatinib given similar presentations described previously in the literature and the patient having no known cardiovascular risk factors. Following angiographic intervention to the coronaries and lower extremities as well as compartment-syndrome fasciotomy, the patient demonstrated clinical improvement.

References

- Tefferi A. Nilotinib treatment-associated accelerated atherosclerosis: when is the risk justified? Leukemia 2013;27:1939-40.

- Cortes JE, Kim DW, Pinilla-Ibarz J, et al. A phase 2 trial of ponatinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1783-96.

- Kim TD, Rea D, Schwarz M, et al. Peripheral artery occlusive disease in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with nilotinib or imatinib. Leukemia 2013;27:1316-21.

- Herrmann J, Yang EH, Iliescu CA, et al. Vascular Toxicities of Cancer Therapies: The Old and the New--An Evolving Avenue. Circulation 2016;133:1272-89.

- Cortes JE, Kantarjian H, Shah NP, et al. Ponatinib in refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2075-88.

- Nicolini FE, Gagnieu MC, Heiblig M, et al. Cardio-Vascular Events Occurring On Ponatinib In Chronic Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients, Preliminary Analysis Of a Multicenter Cohort. Blood 2013;122:4020.

- Racil Z, Razga F, Drapalova J, et al. Mechanism of impaired glucose metabolism during nilotinib therapy in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Haematologica 2013;98:e124-6.

- Maurizot A, Beressi JP, Manéglier B, et al. Rapid clinical improvement of peripheral artery occlusive disease symptoms after nilotinib discontinuation despite persisting vascular occlusion. Blood Cancer J 2014;4: e247.

- Breccia M, Colafigli G, Molica M, Alimena G. Cardiovascular risk assessments in chronic myeloid leukemia allow identification of patients at high risk of cardiovascular events during treatment with nilotinib. Am J Hematol 2015;90:E100-1.

- Herrmann J, Bell MR, Warren RL, Lerman A, Fleming MD, Patnaik M. Complicated and Advanced Atherosclerosis in a Young Woman With Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Success and Challenges of BCR/ABL1-Targeted Cancer Therapy. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:1167-8.

- Moslehi JJ. Cardiovascular Toxic Effects of Targeted Cancer Therapies. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1457-67.