A 56-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension (on amlodipine 10 mg daily, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg daily and lisinopril 40 mg daily), paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (not on anticoagulation), gastroesophageal reflux disease and benign prostatic hypertrophy, presented to the emergency room for chest pain and decreased exercise tolerance of 7 days duration.

Ten days ago, the patient developed flu-like symptoms. He was started on amoxicillin and clavulanate for concern for a bacterial upper respiratory infection. His respiratory symptoms resolved in about 3 days; however, he began developing pleuritic chest pain relieved on bending forward associated with shortness of breath at exertion. He also had bouts of self-resolving atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response. Colchicine and aspirin 325 mg twice daily were started; however, his symptoms worsened. An echocardiogram was done as an outpatient for suspicion for acute pericarditis and showed a large circumferential pericardial effusion without evidence of constrictive physiology or tamponade. He was then started on oral methylprednisolone and referred to the emergency department.

The patient was in his usual state of health until 4 months ago, when he presented to the emergency room with similar chest pain. He underwent a computed tomography angiography of his chest, which was negative for pulmonary embolism or any acute pulmonary process. Echocardiography revealed small circumferential pericardial effusion. He was diagnosed with acute pericarditis and discharged on 4 days of colchicine 0.4 mg three times daily, and he became symptom-free in a few days. He also had a stress test completed after the initial episode, and it was negative.

On arrival, his temperature was 36.3 degrees Celsius, pulse was 64 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 14 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 147/88 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. His physical exam showed a jugular venous pressure of 15 cm water, and regular S1 and S2 and was negative for a pericardial rub, Kussmaul's sign, pulsus paradoxus or lower limb edema.

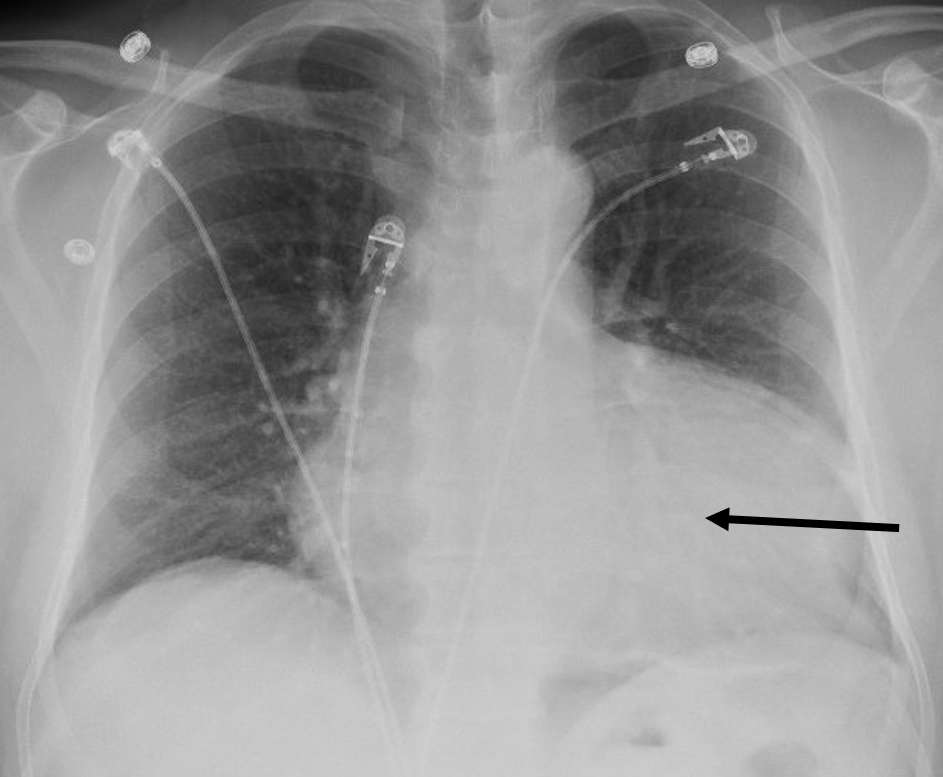

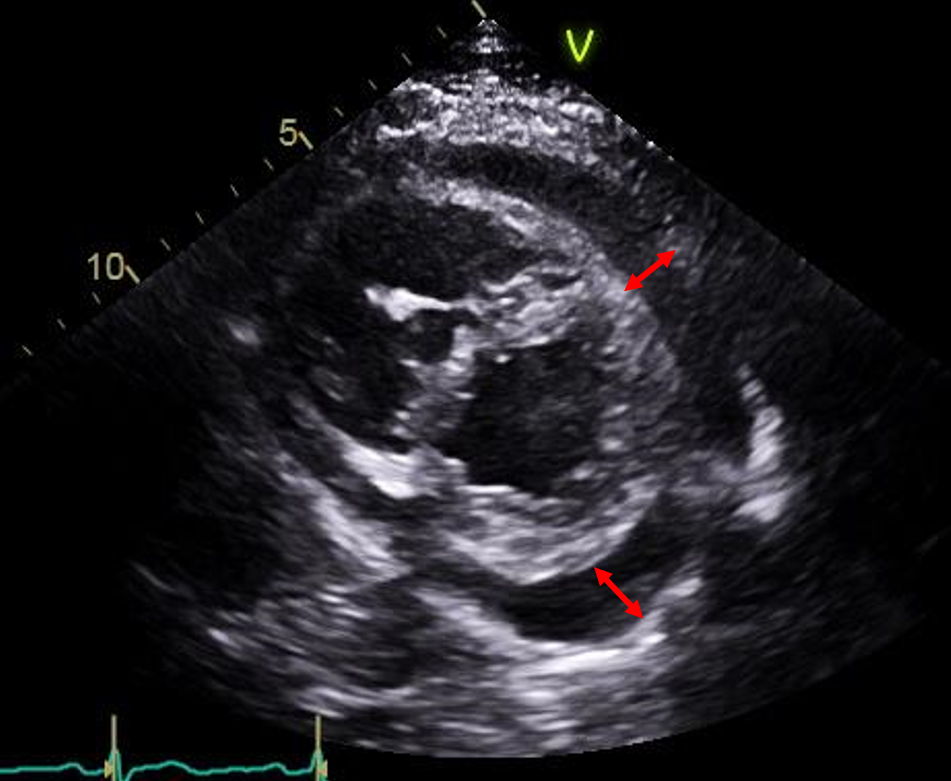

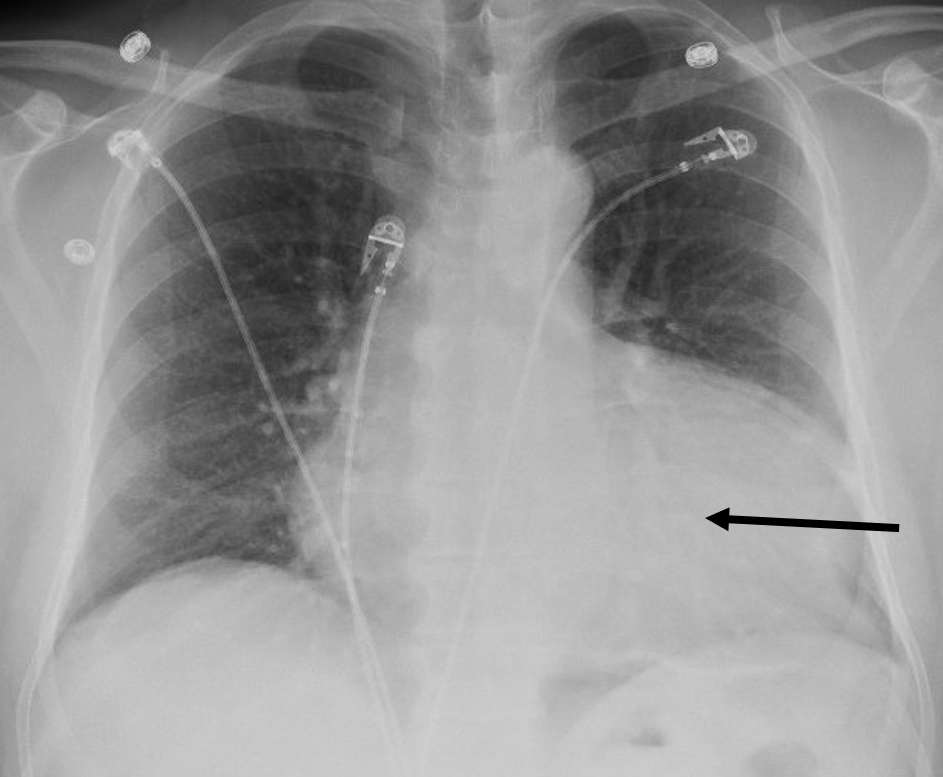

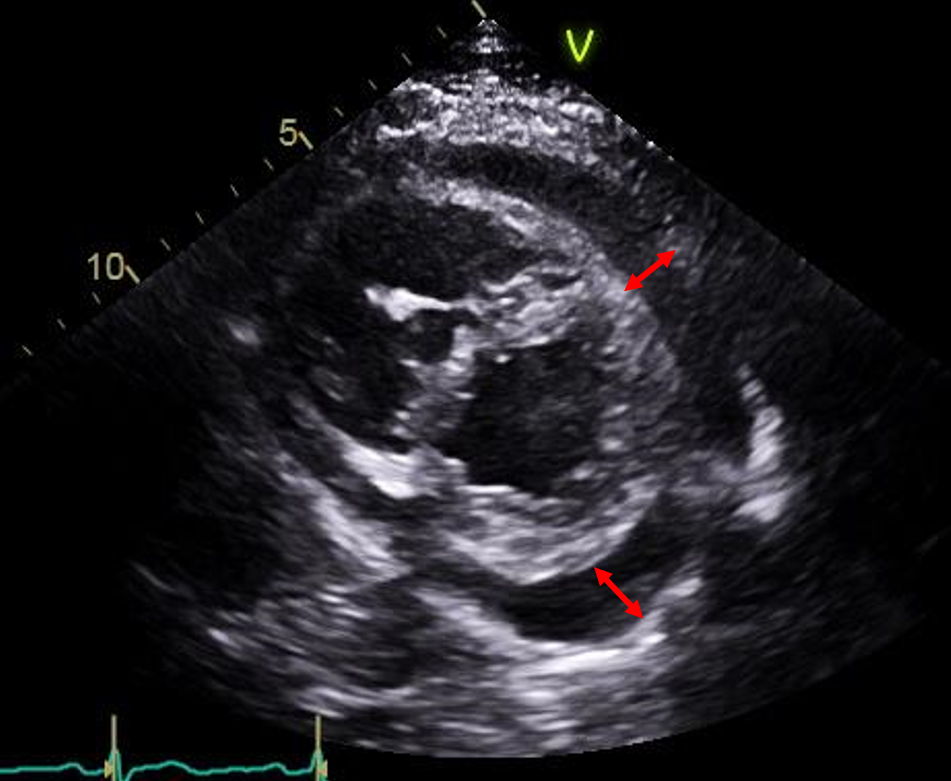

His laboratory workup showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 29 mm/hour (normal range: 0 - 20 mm/hour), a C-reactive protein of 2.7 mg/dl (normal range: less than 0.9 mg/dl), NT-proBNP of 296 (normal range: less than 125 pg/ml), normal kidney function, negative cardiac enzymes, hemoglobin of 15.3 g/dl (normal range: 11.5 - 15.5 g/dl), platelets of 266 k/uL (normal range: 150-400 k/ul), Coxsackie B type 4 titer of 1:320 (normal range: less than 1:10), normal autoimmune workup, negative HIV, and negative tuberculosis. His electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with no electrical alternans, PR depression or ST elevation. Chest X-ray revealed an enlargement of the cardiac silhouette (Figure 1). A transthoracic echocardiogram showed a large circumferential pericardial effusion measuring 2.6 cm. There was no diastolic chamber collapse; however, the inferior vena cava measured 2.4 cm and decreased less than 50% with inspiration, and the respiratory inflow variations across the tricuspid and mitral valves were 41% and 13.7% respectively (Figure 2). Cardiac MRI done showed pericardial delayed enhancement on fat-suppressed sequences without constrictive physiology (Figure 3). The patient was started on colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily, aspirin 650 mg twice daily and prednisone 30 mg daily and had pericardiocentesis the next day with 430 ml of bloody fluid drained. Pericardial fluid analysis and cultures were negative for tuberculosis, fungal or bacterial infections. His symptoms improved and he was discharged on colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily, aspirin 650 mg twice daily, prednisone 30 mg once daily and was advised to restrict exercising.

Figure 1

Figure 1: Chest X ray showing enlargement of the heart silhouette (black arrow).

Figure 1: Chest X ray showing enlargement of the heart silhouette (black arrow).

Figure 2

Figure 2: Transthoracic echocardiography, parasternal short axis view, showing circumferential pericardial effusion (red double arrows).

Figure 2: Transthoracic echocardiography, parasternal short axis view, showing circumferential pericardial effusion (red double arrows).

Figure 3

Figure 3: Cardiac MRI phase sensitive inversion recovery fat suppressed sequence showing delayed pericardial enhancement (orange arrow) with a large size pericardial effusion (red arrow).

Figure 3: Cardiac MRI phase sensitive inversion recovery fat suppressed sequence showing delayed pericardial enhancement (orange arrow) with a large size pericardial effusion (red arrow).

The correct answer is: C. Suboptimal duration of colchicine treatment at the patient's initial episode.

During his initial event, he only received 4 days of colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily. Although the optimal duration of colchicine is yet to be determined, the most recent randomized trials used a treatment dose of colchicine of 0.5 to 1 mg daily for 3 months.1,2 The addition of colchicine to the treatment regimen at this dose has been proven effective to prevent recurrences of pericarditis.1-4 In a meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials, colchicine has been shown to decrease the risk of recurrence of pericarditis or postpericardiotomy syndrome (RR 0.5, p < 0.0001).5 The 2015 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases recommended early initiation of colchicine for 3 months duration with optional tapering, in adjunct to non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).6 Thus, a treatment duration of colchicine of 4 days is unlikely to be sufficient to prevent future recurrences of an initial acute pericarditis episode.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are very effective in symptom control and resolution of the acute episode. A randomized controlled trial comparing aspirin and ibuprofen to placebo in postpericardiotomy syndrome showed clear efficacy of those medications (89-90% versus 62.5% effective, p-value 0.003).7 However, unlike colchicine, there is no convincing evidence that NSAIDs modify the disease course or decrease the risk of recurrence. NSAIDs generally act within 48 hours8 and should be continued until resolution of the symptoms and normalization of the inflammatory markers, as by the 2015 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases.6 Although NSAIDs remain first-line treatment in acute pericarditis, the patient's symptoms resolved spontaneously within a few days of the initial episode (and he remained symptom-free for 4 months), and the addition of NSAIDs at the initial presentation would not have prevented further recurrences.

Steroids, on the other hand, have been proven to increase the risk of recurrence, mostly due to fast tapering, and they should not be the first-line treatment in the vast majority of cases. If needed, low dose corticosteroids with slow tapering should be started after the failure of first-line treatment.9 Artom et al. have shown that corticosteroids can even decrease the efficacy of colchicine in preventing recurrences.10 In another retrospective study comparing high dose to low dose steroids in recurrent pericarditis, the former was associated with a higher risk of recurrences (64.7% versus 32.6%, p=0.002) and side effects (23.5% versus 2%, p=0.002).11 In this patient, the early initiation of corticosteroids would have increased his risk of recurrence with the burden of additional side effects.

In the cases of resistance to NSAIDs, colchicine, and steroids (or inability to wean down steroids), immunomodulatory therapy should be tried. Those include azathioprine, human intravenous immunoglobulins, and inhibitors of interleukin 1 (anakinra, canakinumab or rilonacept).4,6,9,12,13 Further large sample randomized controlled trials are needed to prove the efficacy of those regimens and many trials are underway.14 Pericardiectomy is the last resort and should be done by experts in this surgery.

References

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Cemin R, et al. A randomized trial of colchicine for acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1522-28.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute Pericarditis: Results of the COlchicine for acute PEricardits (COPE) trial. Circulation 2005;112:2012-16.

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Forno D, et al. Efficacy and safety of colchicine for pericarditis prevention. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2012;98:1078-82.

- Cremer PC, Kumar A, Kontzias A, et al. Complicated pericarditis: Understanding risk factors and pathophysiology to inform imaging and treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2311-28.

- Verma S, Eikelboom JW, Nidorf SM, et al. Colchicine in cardiac disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2015;15:96.

- Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by: The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2015;36:2921-64.

- Horneffer PJ, Miller RH, Pearson TA, Rykiel MF, Reitz BA, Gardner TJ. The effective treatment of postpericardiotomy syndrome after cardiac operations. A randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1990;100:292-96. .

- Berman J, Haffajee CI, Alpert JS. Therapy of symptomatic pericarditis after myocardial infarction: retrospective and prospective studies of aspirin, indomethacin, prednisone, and spontaneous resolution. Am Heart J. 1981;101:750-53.

- Xu B, Harb SC, Cremer PC. New insights into pericarditis: Mechanisms of injury and therapeutic targets. Curr Cardiol Rep 2017;19:60.

- Artom G, Koren-Morag N, Spodick DH, et al. Pretreatment with corticosteroids attenuates the efficacy of colchicine in preventing recurrent pericarditis: A multi-centre all-case analysis. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:723-727.

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Cumetti D, et al. Corticosteroids for recurrent pericarditis: high versus low doses: A nonrandomized observation Circulation. 2008;118:667-71.

- Lazaros G, Antonatou K, Vassilopoulos D. The therapeutic role of interleukin-1inhibition in idiopathic recurrent pericarditis: Current evidence and future challenges. Front Med 2017;4:78.

- Van Tassell BW, Toldo S, Mezzaroma E, Abbate A. Targeting interleukin-1 in heart disease. Circulation 2013;128:1910-23

- Klein A, Lin D, Cremer P, et al. Rilonacept in recurrent pericarditis: First efficacy and safety data from an ongoing phase 2 pilot clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1261.