A 54-year-old male, highly active firefighter with a medical history significant for prostate cancer and subsequent radical prostatectomy presented to our Sports Cardiology Clinic with acute onset shortness of breath disproportionate to his perceived level of exertion. The patient is a multisport athlete, running 20-25 miles per week and rowing on his home ergometer two sessions per week dating back to his 20s. His training consisted of a mix of high intensity interval training and aerobic work during this time. Due to COVID-19 pandemic, the patient was initially evaluated via telehealth. He underwent a radical prostatectomy 6 weeks prior to presentation at another institution with an uncomplicated course. His symptoms began upon returning to activity once safe to do so per his urologist. He described activity-limiting shortness of breath after running one mile that progressed to shortness of breath and near syncope while mowing his lawn over the course of one week. He denied chest pain, palpitations, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea or leg edema. He denied any preceding fevers, chills or sick contacts and denied any known exposure to COVID-19. He did describe a significant amount of dust and fire exposure during his tenure as a firefighter (31 years) but stated that he always wore his protective equipment. His only medication is tadalafil prescribed by his urologist postoperatively. He does not smoke or drink alcohol and uses no illicit or performance enhancing drugs. He has no family history of heart disease or sudden death. His blood pressure was 118/64, pulse 59 bpm and he had a normal cardiac exam. Laboratory tests showed dyslipidemia with cholesterol 232 mg/dL and LDL 194 mg/dL. Otherwise, complete blood counts, renal function, hepatic function, thyroid function, and electrolytes were all within normal range.

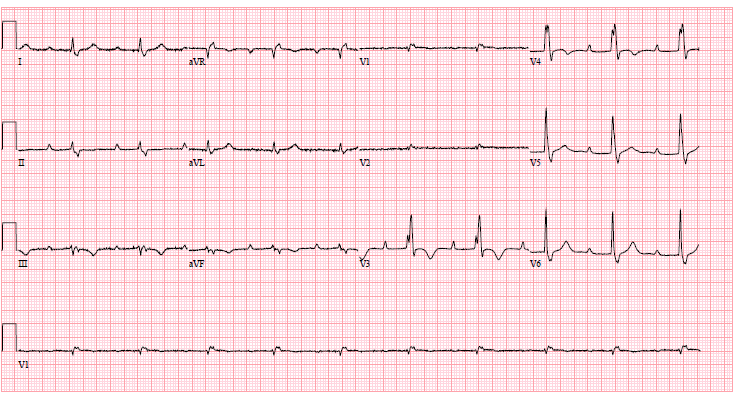

Given his symptoms, we elected to proceed with a stress echocardiogram for further evaluation. His baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) (Figure 1) showed sinus bradycardia with a first degree atrioventricular (AV) block, right bundle branch block with inferior and anterior T wave abnormalities. No prior ECG was available for comparison. His baseline, resting echocardiogram disclosed asymmetric septal hypertrophy (basal anteroseptum 1.6 cm, posterolateral wall 1.2 cm). His left ventricular systolic function was mildly reduced, with a left ventricular ejection fraction measuring 50% by Simpson's method. Regional wall motion abnormalities were well visualized, specifically basal inferior, mid inferior and apical inferior wall hypokinesis. There were no other significant structural or functional abnormalities.

Figure 1

Due to the abnormal baseline echocardiographic findings, the stress portion of his study was cancelled, and a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was ordered. Findings were notable for the following:

- Left ventricle was normal in size with mildly reduced systolic function, ejection fraction (44%). The thickest segments were the basal anterior and basal anteroseptal walls measuring 1.6 cm.

- Right ventricle was mildly dilated with severely reduced systolic function (27%).

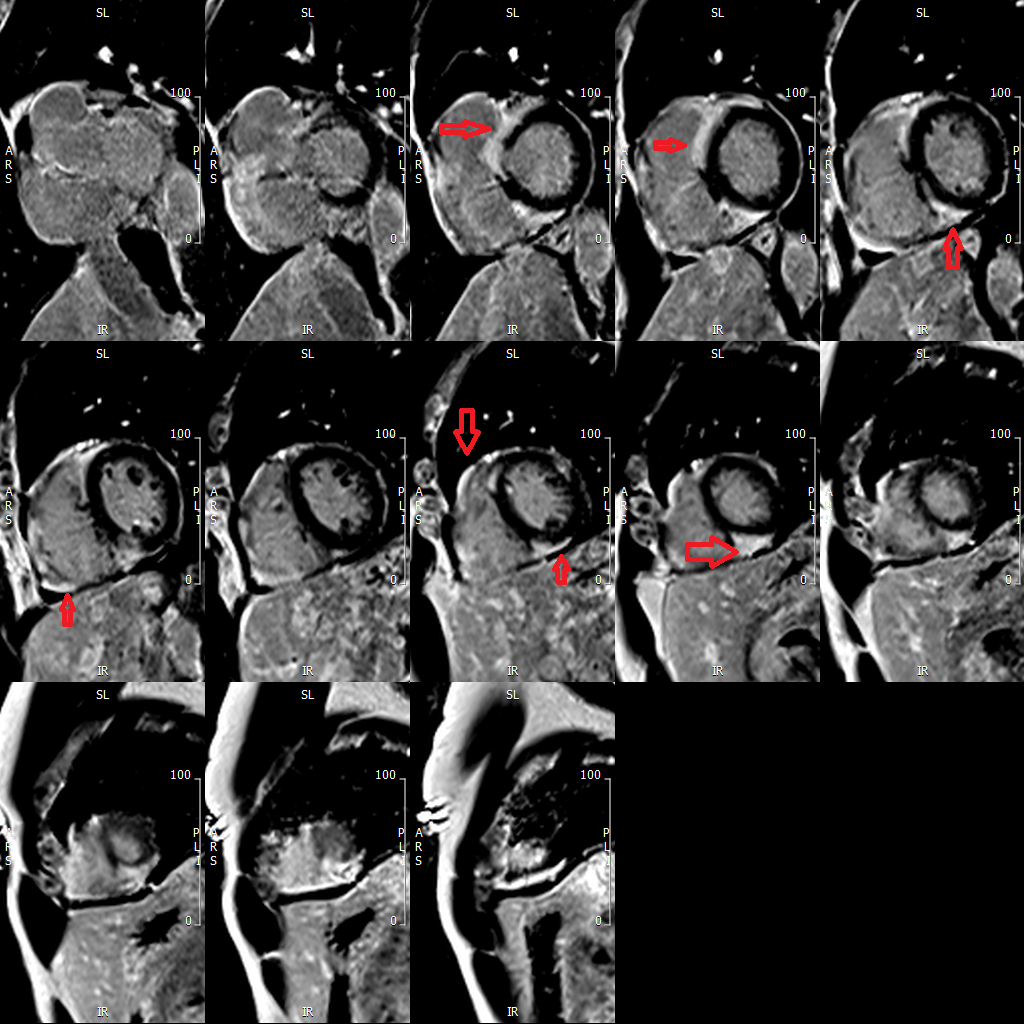

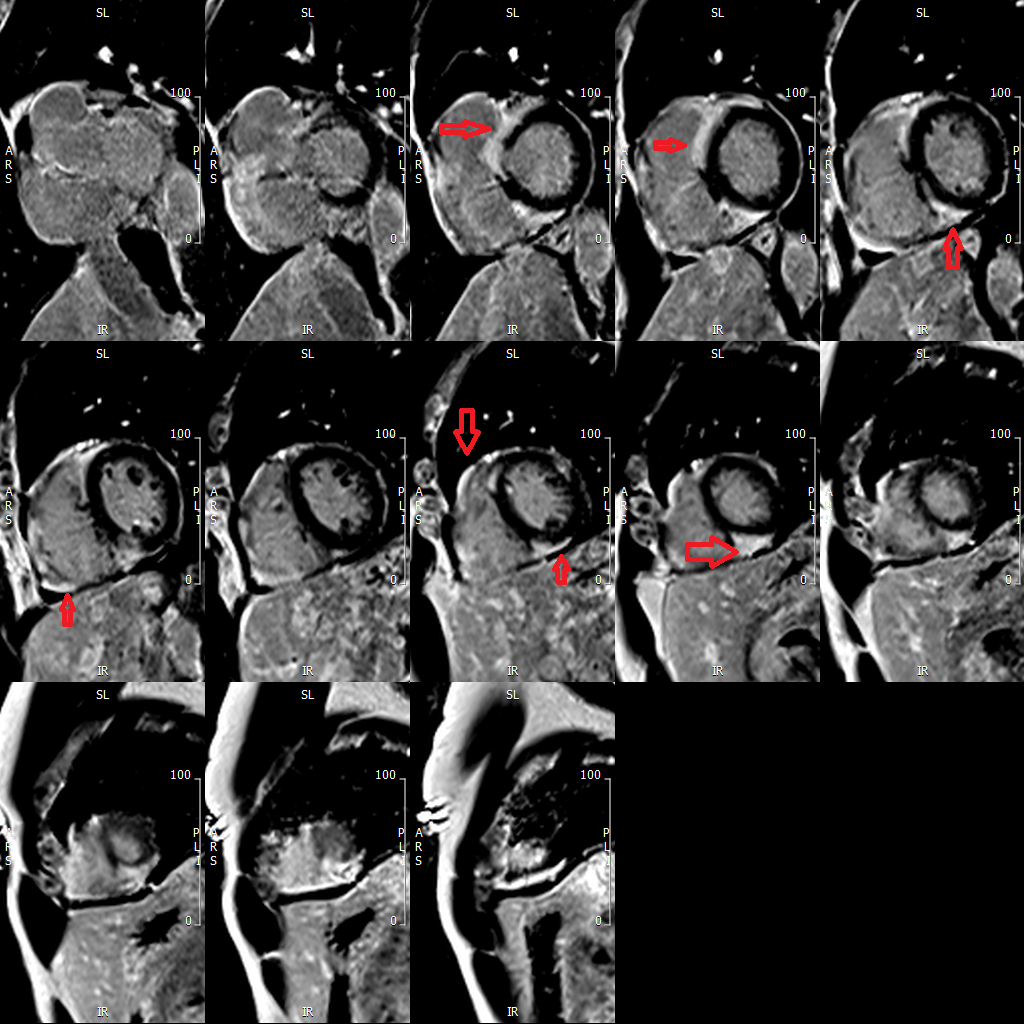

- On delayed gadolinium imaging, there is patchy subepicardial to transmural enhancement involving both left and right ventricles. Enhancement in the left ventricle is seen in the basal to mid septum, basal anterior wall, mid to apical inferoseptal-inferior wall and apical lateral wall. Enhancement is also seen in the right ventricular free wall. (Figure 2)

Figure 2

Short axis delayed gadolinium images of the ventricle. Red arrows point to the multiple patchy areas of sub-epicardial enhancement in both the left and right ventricles, typically seen in cardiac sarcoidosis.

Short axis delayed gadolinium images of the ventricle. Red arrows point to the multiple patchy areas of sub-epicardial enhancement in both the left and right ventricles, typically seen in cardiac sarcoidosis.

Short axis delayed gadolinium images of the ventricle. Red arrows point to the multiple patchy areas of sub-epicardial enhancement in both the left and right ventricles, typically seen in cardiac sarcoidosis.

The correct answer is: B. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (i.e. cardiac PET)

We present a case of new exertional dyspnea in a highly athletic middle-aged male after his uncomplicated prostate surgery. The patient's sudden onset and severity of symptoms are concerning. We elected to proceed with a stress echocardiogram as an initial first step. His baseline echocardiogram findings initially heightened suspicion for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, though the findings on his cardiac MRI of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in both the left and right ventricles with surrounding edema raised a differential diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis versus acute myocarditis. As a result, we felt it was most reasonable to obtain a cardiac PET scan as our next step. This study disclosed multiple areas of heterogeneous high-grade cardiac uptake that correlated to the areas of LGE seen on the MRI in both the right and left ventricles. Also noted were areas of high-grade uptake throughout lungs and hilar regions. Together, these findings were consistent with metabolically active cardiac and pulmonary sarcoidosis. The patient was started on high dose steroids, a cardiac event monitor was placed, and plans were made for a repeat PET scan in 4-6 weeks. He reported a significant improvement in his symptoms after 1 week of steroids. He was counseled to continue to abstain from exercise until follow up.

Sarcoidosis in firefighters has been reported in prior literature, particularly after the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center (WTC) on September 11, 2001. Reports are notable for an increased rate of sarcoid-like disease in firefighters from WTC dust exposure within the first year of the attack, with an incidence rate of 86/100,000 after 1 year and 22/100,00 after 4 years.1 The incidence rate was markedly higher than what it had previously been during the 15 years prior to the attack (15/100,000).2 While our patient was not present at the WTC at the time of the attacks, he did admit to a significant amount of particle exposure over his career. Studies have shown an increase prevalence of sarcoid in firefighters compared to other first responders.3,4 Because of these findings, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health created recommendations to monitor the health and safety of firefighters as it relates to sarcoidosis and occupational exposure.5 The true incidence of cardiac sarcoid in this population remains unknown. Thus, sarcoidosis is an important diagnosis to consider in fire fighters and other tactical athletes with high volumes of particle exposure who present with cardiac and pulmonary symptoms.

References

- Perlman SE, Friedman S, Galea S, et al. Short-term and medium-term health effects of 9/11. Lancet 2011;378:925-34.

- Izbicki G, Chavko R, Banauch GI, et al. World Trade Center "sarcoid-like" granulomatous pulmonary disease in New York City Fire Department rescue workers. Chest 2007;131:1414-23.

- Prezant DJ, Dhala A, Goldstein A, et al. The incidence, prevalence, and severity of sarcoidosis in New York City Firefighters. Chest 1999;116:1183-93.

- Kern DG, Neill MA, Wrenn DS, Varone JC. Investigation of a unique time-space cluster of sarcoidosis in fire fighters. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;148:974–80.

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Death in the line of duty: a summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation (CDC website). 2013. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face201303.html. Accessed 05/01/2020.