A 52-year-old man with a past medical history of severe aortic regurgitation status post a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement 2 years prior and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction who presents with chest pain.

He presented to the emergency department where he complained of sharp chest pain that radiated to his neck and back. He underwent a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) which showed an ejection fraction (EF) of 40%, improved from 25% at the time of his aortic valve surgery, and a new, moderate pericardial effusion. He was diagnosed with acute pericarditis and discharged on prednisone.

He presented several months later with recurrent chest pain along with a 25 pound weight gain and dyspnea on exertion. He underwent a repeat TTE which showed an EF of 35% with anterior septum akinesis and basal inferoseptal, mid inferoseptal, and inferior hypokinesis. He was noted to have a mildly thickened pericardium, but no evidence of constriction. Left heart catheterization was notable for non-obstructive coronary artery disease.

During this hospitalization, he also underwent non-contrasted computed tomography (CT) of his chest which was significant for hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. He subsequently underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) which showed thickening and delayed enhancement of the pericardium along the free wall of the right ventricle and the distal anterior wall concerning for pericardial inflammation (Figures 1 and 2). The study was also notable for severe hypokinesis of the entire basal and mid-septum with delayed enhancement of the entire basal septum, not consistent with an ischemic pattern. His findings raised the concern for perimyocarditis and sarcoidosis.

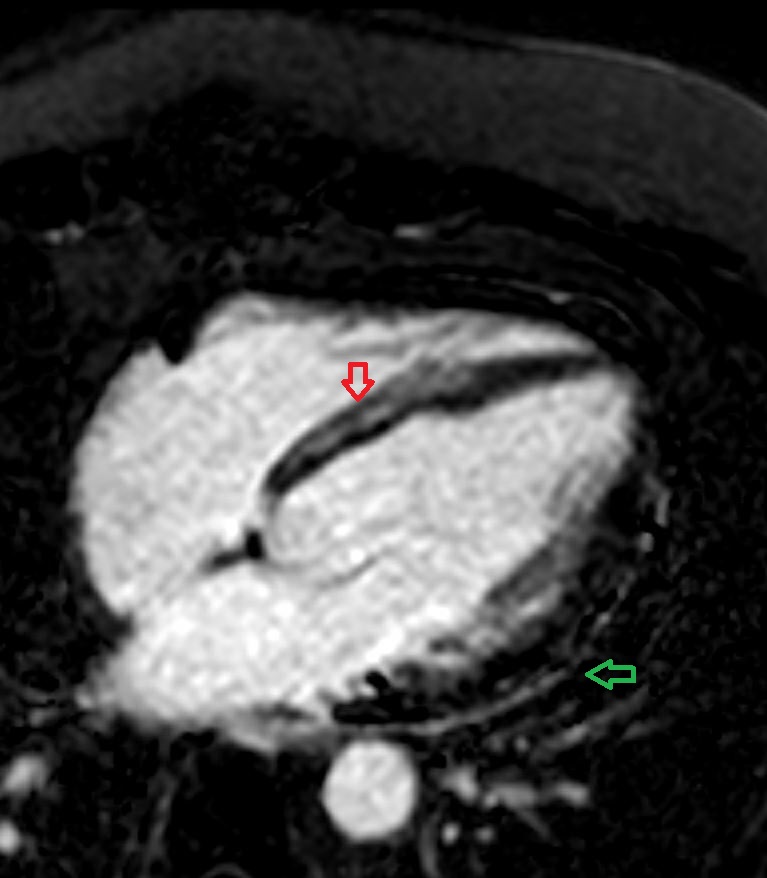

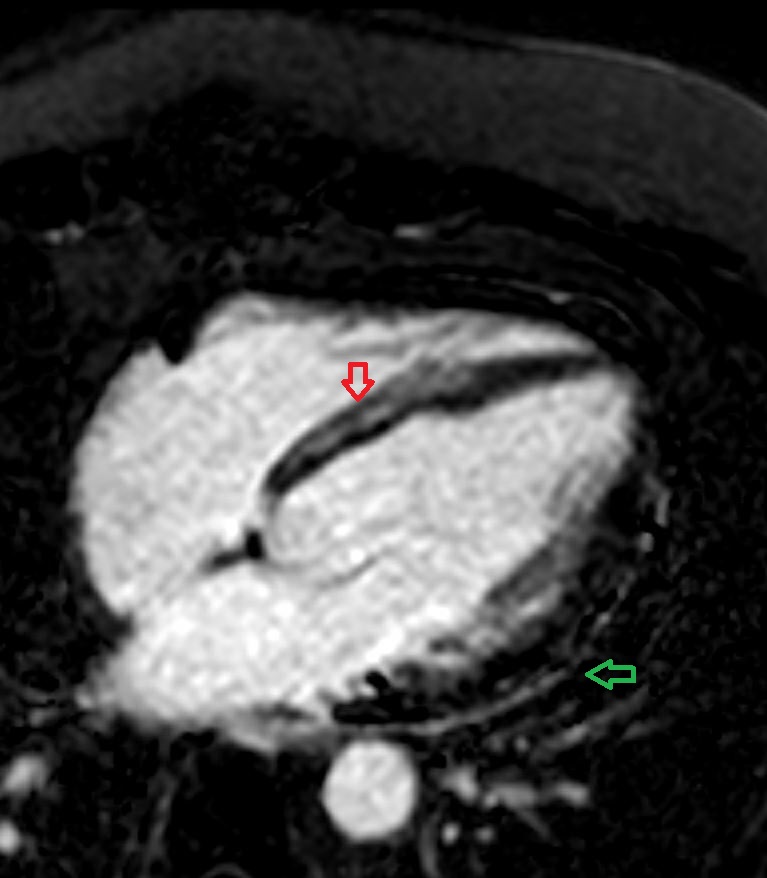

Figure 1

Figure 1: Cardiac MRI 4-chamber view with fat suppression showing late gadolinium enhancement of the pericardium (green) and mid-wall of the basal and mid septum (red arrow).

Figure 1: Cardiac MRI 4-chamber view with fat suppression showing late gadolinium enhancement of the pericardium (green) and mid-wall of the basal and mid septum (red arrow).

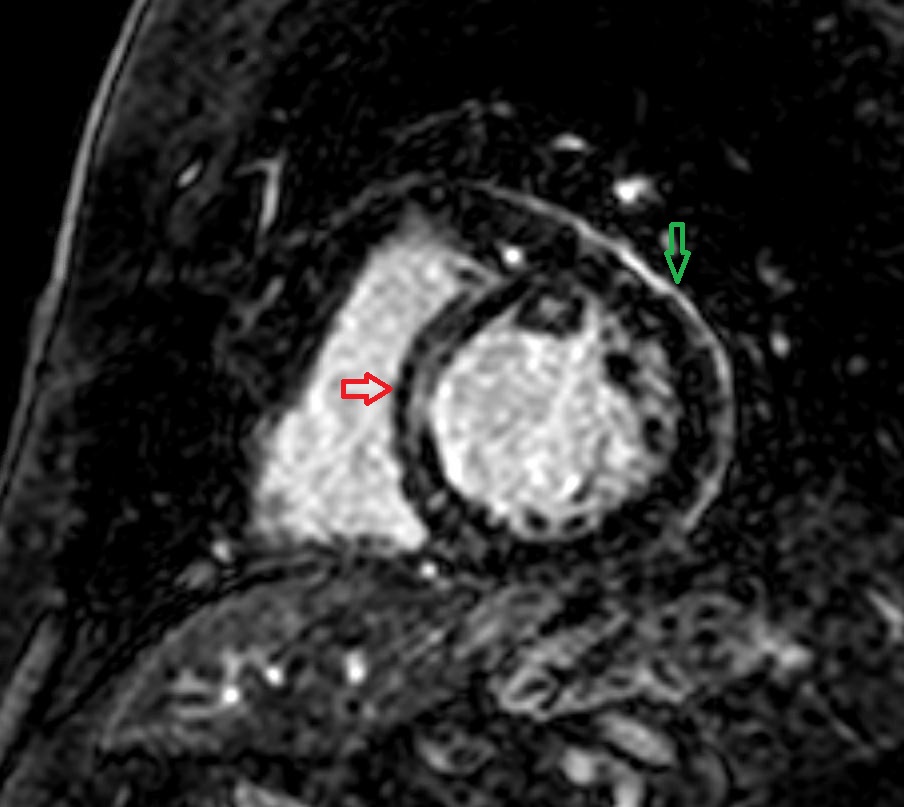

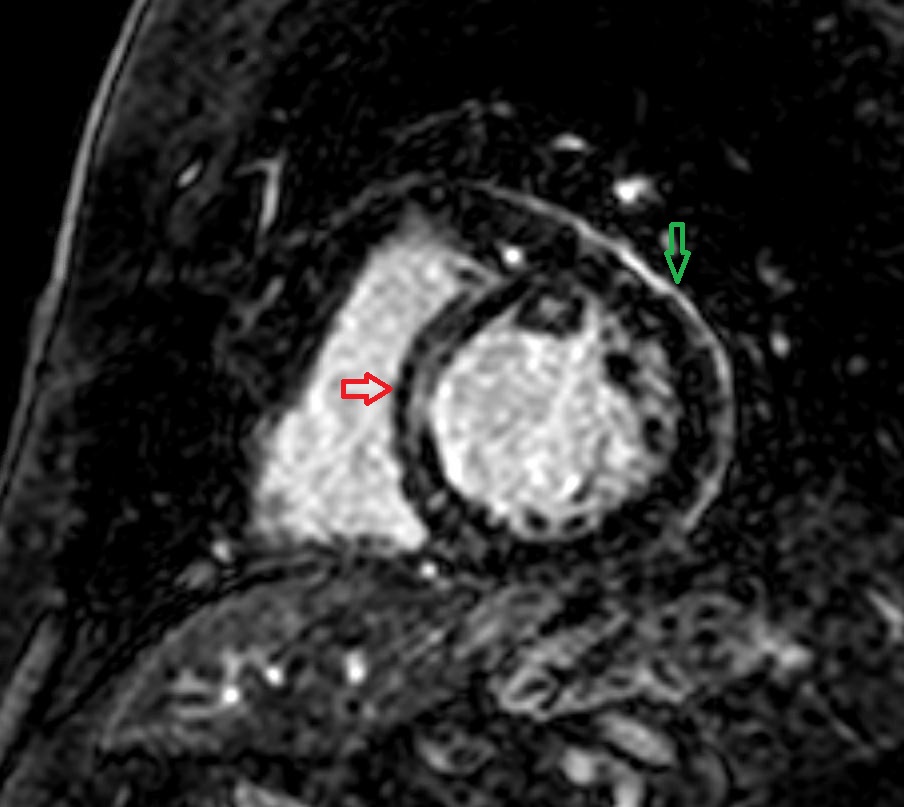

Figure 2

Figure 2: Cardiac MRI short axis view with fat suppression showing late gadolinium enhancement of the pericardium (green) and mid-wall of the basal and mid septum (red arrow).

Figure 2: Cardiac MRI short axis view with fat suppression showing late gadolinium enhancement of the pericardium (green) and mid-wall of the basal and mid septum (red arrow).

At this time, he also underwent positron emission tomography (PET) of the heart which showed areas of enhanced fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the basal anteroseptal and basal inferolateral myocardial segments.

Based on the results of his CT chest, CMR, and PET scan, he was diagnosed with both cardiac and pericardial sarcoidosis. The recurrent pericarditis was treated with prednisone, ibuprofen, and colchicine. He was started on goal-directed medical therapy for heart failure and underwent placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. He unfortunately has had many subsequent episodes of recurrent pericarditis with tapering of his glucocorticoids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDS) and has been unable to come off of these medications. Despite medical therapy, his heart failure has progressed to stage D and is undergoing evaluation for advanced therapies.

The correct answer is: D. Asymptomatic pericardial effusion is the most common manifestation of pericardial sarcoidosis.

Cardiac sarcoidosis affects approximately 5% of patients with sarcoidosis yet is responsible for up to 85% of the mortality.1 Cardiac sarcoidosis is a very challenging diagnosis because endomyocardial biopsy, the gold standard, has low sensitivity of 25%. For this reason, the importance of multimodality imaging with echocardiography, PET-CT, and CMR has increased.2

On transthoracic echocardiography, cardiac sarcoidosis classically causes thinning and hypokinesis of the septum, particularly the basal segment, along with a dilated cardiomyopathy.2 However, cardiac sarcoidosis can also present as a restrictive cardiomyopathy in 5% of patients.3 Cardiac sarcoidosis classically shows late gadolinium enhancement on CMR in a patchy and multifocal distribution, sparing the endocardial border. Compared to other modalities, CMR can best qualify and quantify myocardial fibrosis. Lastly, PET-CT is the imaging modality that best identifies actively inflamed tissue. These three imaging modality can be used in conjunction to not only diagnose cardiac sarcoidosis, but often guide management.4

Cardiac sarcoidosis typically presents with myocardial or electrical dysfunction and rarely causes clinically manifest pericardial disease with asymptomatic pericardial effusions as the most common manifestation of pericardial sarcoid.5 Case reports exist of other rare manifestations of pericardial involvement such as acute pericarditis, constrictive-effusive pericarditis, and cardiac tamponade.5-7 This case describes a very rare combination of clinically significant myocardial dysfunction along with recurrent pericarditis. CMR is the most comprehensive modality for assessing the pericardium, allowing for both morphologic characterization of the pericardium as well as the assessment of hemodynamic parameters. Pericardial inflammation results in increased and delayed enhancement of gadolinium within the pericardium. Serial CMR has proven to be a more reliably guide treatment for recurrent pericarditis than traditional inflammatory biomarkers.8

References

- Okada DR, Smith J, Derakhshan A, et al. Ventricular arrhythmias in cardiac sarcoidosis. Circulation 2018;138:1253-64.

- Birnie DH, Nery PB, Ha AC, Beanlands RSB. Cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:411-21.

- Falk R, Hershberger R. "The Dilated, Restrictive, and Infiltrative Cardiomyopathies". In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Elsevier Inc.;2019:1580-1601.

- Vita T, Okada DR, Veillet-Chowdhury M, et al. Complementary value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the assessment of cardiac sarcoidosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11:e007030.

- Peña-Garcia JI, Shaikh SJ, Villacis-Nunez DS, Gurram MK. Pericardial effusion in systemic sarcoidosis: a rare manifestation of cardiac sarcoid. Heart Views 2019;20:56-59.

- Darda S, Zughaib ME, Alexander PB, Machado CE, David SW, Saba S. Cardiac sarcoidosis presenting as constrictive pericarditis. Tex Heart Inst J 2014;41:319-23.

- Valentin R, Keeley EC, Ataya A, et al. Breaking hearts and taking names: A case of sarcoidosis related effusive-constrictive pericarditis. Respir Med 2020;163:105879.

- Chetrit M, Xu B, Kwon DH, et al. Imaging-guided therapies for pericardial diseases. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;13:1422-37.