A 32-year-old woman with lower extremity claudication, sickle cell trait, depression, and history of intrauterine fetal demise presents to the vascular medicine clinic complaining bilateral lower extremity pain.

The patient states that she has noticed a slow worsening of her bilateral lower extremity claudication for the past 3 years. She was previously able to walk 1-2 blocks with pain in her calves, but now she has pain that has progressed proximally to her thighs and occurs after only ½ block. She is forced to rest for about 10 minutes before the pain subsides; the patient has no pain at rest. She also endorses numbness in her feet at night but improve in a dependent position. The patient is a 12 pack-year smoker but quit 2 years ago. She denies alcohol and illicit drug use. Family history is significant with a mother who died of sudden cardiac death at 54, and a father who died swimming at 23. Her outpatient medications are buspirone 7.5mg twice a day, gabapentin 300mg twice a day, and sertraline 50mg daily.

Laboratory work including C-reactive peptide, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, homocysteine, lipoprotein-a, cardiolipin antibody, and lupus anticoagulant were all within normal limits. Lipid panel demonstrates LDL 69 mg/dL, HDL 41mg/dL, triglycerides 61 mg/dL, and total cholesterol 122 mg/dL. Glycohemoglobin A1c is 4.7%. On physical exam, the patient's lower extremities are warm, but femoral and lower extremity peripheral pulses unable to be palpated. Pulses were monophasic bilaterally via handheld Doppler. Capillary refill is <2 seconds in her bilateral great toes. She has normal muscle strength and tone in her lower extremities. Lower extremity reflexes are intact and straight leg raise is negative bilaterally. Sensation is intact to light touch and vibration bilaterally.

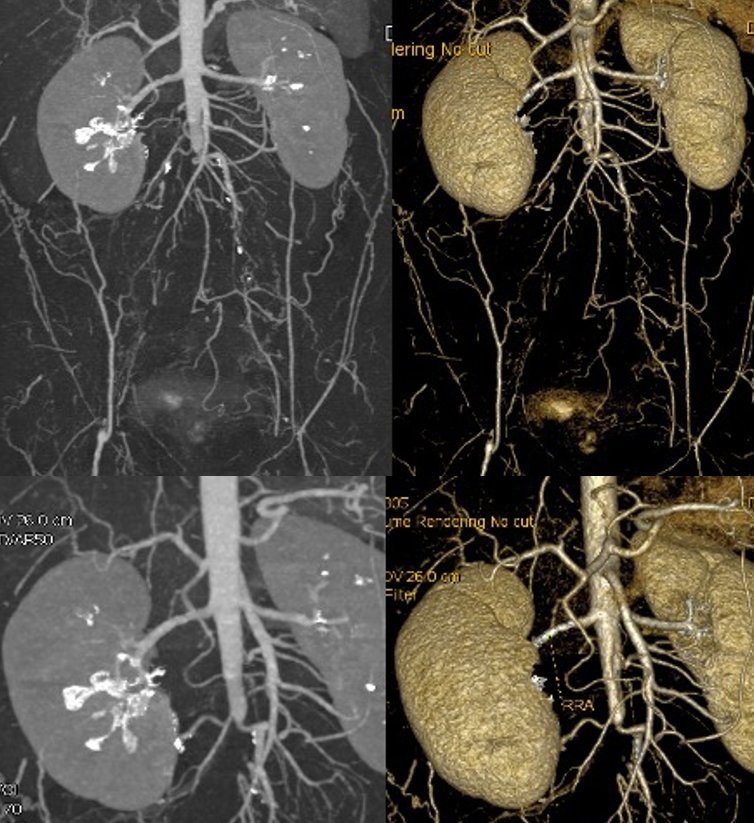

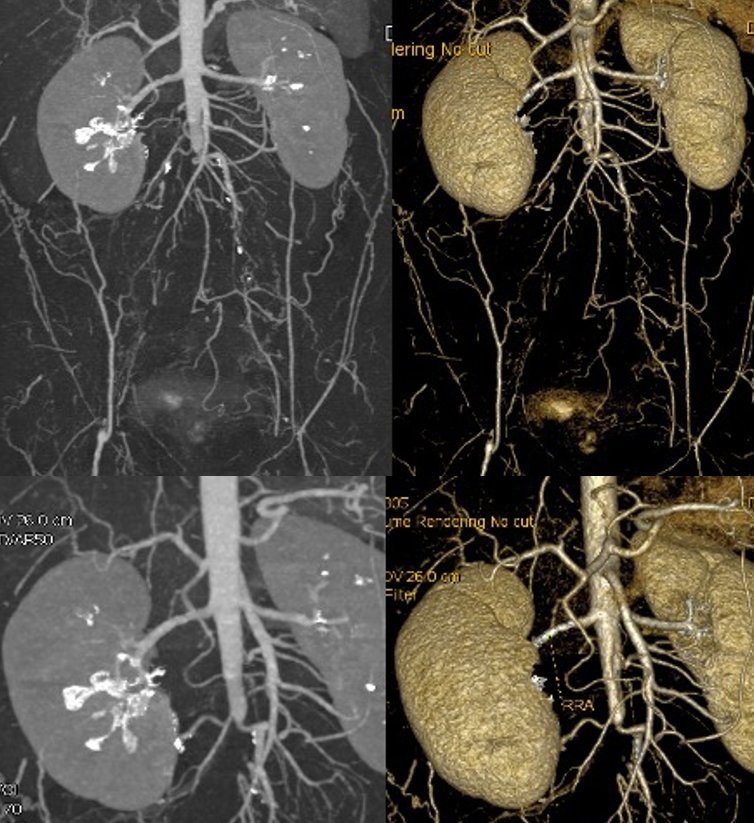

Ankle-brachial index (ABI) values at rest are 0.34 on the right and 0.54 on the left. There are monophasic dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial waveforms bilaterally. Computed tomography angiogram (CTA) abdomen with runoff demonstrates an occluded aorta distally, occluded iliac arteries bilaterally, reconstitution of small common femoral arteries (CFA) bilaterally, with superficial femoral artery and popliteal artery occlusion bilaterally and reconstitution of tibial vessel bilaterally (Figure 1). Bilateral lower extremity duplex ultrasounds show no evidence of deep vein thrombosis and patent great saphenous and superficial saphenous veins bilaterally.

Figure 1

Figure 1: CTA abdomen demonstrating occluded aorta distally, occluded iliacs bilaterally, and reconstitution of small CFA bilaterally

Figure 1: CTA abdomen demonstrating occluded aorta distally, occluded iliacs bilaterally, and reconstitution of small CFA bilaterally

The correct answer is: A. Conservative therapy with aspirin, statin, cilostazol, and structured exercise program

This patient's claudication symptoms are from her significant peripheral arterial disease (PAD). The estimated prevalence of PAD is 200 million people worldwide with a total annual cost of hospitalization in the United States (US) estimated to be >$21 billion.1 Broadly, PAD refers to pathology in non-cardiac and non-cerebral arteries. The most common cause of PAD is atherosclerosis, and thus the strongest risk factors are smoking, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.1 Other etiologies of PAD include inflammatory disorders such as vasculitis and other arteriopathies such as fibromuscular dysplasia. More than half of the patients with PAD have comorbid conditions including coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, or both.1 An ABI of 0.9 or less is associated with twice the mortality of an ABI of 1.11 to 1.40.1

A majority of patients with PAD are asymptomatic which contributes to why PAD is underdiagnosed and undertreated.2 Symptomatic patients complain of fatigue, discomfort, cramping, or pain when the affected muscles groups are exerted.2 This commonly presents as lower extremity pain when walking but relieved at rest. For treatment and prognosis, it is important to differentiate patients with claudication versus critical limb ischemia or acute limb ischemia. Providers should have high clinical suspicion for critical limb ischemia in patients who have pain at rest or ulceration on examination.

Both US and European guidelines agree that ABI should be the first study used in the diagnosis of PAD.3 Toe-brachial index (TBI) is the next best step in patients who have non-compressible arteries because that can artificially elevate the ABI. An ABI <0.9 or a TBI <0.7 is diagnostic of PAD.2 Both US and European guidelines recommend against screening asymptomatic patients, and they also recommend against duplex ultrasound, computed tomography angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, or catheter-based angiography in initial diagnosis.3 However, these can be considered to diagnose anatomic location and severity of stenosis for patients with symptomatic PAD who are being considered for revascularization.2

The three main goals for treating patients with PAD are to reduce cardiovascular outcomes, increase functional capacity, and prevent limb ischemia.1 In terms of treatment, both the US and European guidelines address targeting risk factors for atherosclerotic disease.3 They both issue Class I recommendations for smoking cessation, tight glycemic control, statin therapy and strict blood pressure management.3

In addition to controlling risk factors, first line treatment for PAD includes antiplatelet therapy, structured exercise therapy, and cilostazol.2 In terms of antiplatelet agent, patients should be started on aspirin (75-325mg daily) or clopidogrel (75mg daily), although the latter has been found to be slightly more effective in reducing a composite outcome of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from vascular causes.4 Ticagrelor was not shown to be superior to clopidogrel for the reduction of cardiovascular events, and had similar rates of major bleeding.5 The effectiveness of dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel in reducing cardiovascular events has not been well established.2 A structured exercise program includes walking at least three times a week for 30-60 minutes for at least 12 weeks.2 This is aimed at helping improve patients' functional capacity. Finally, cilostazol is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor which has been proven to increase walking distance on a treadmill by 25% compared to placebo.1

In this patient, treatment should first be started with goal-directed medical therapy (GDMT) including a statin, aspirin, structured exercise program, and cilostazol. She has no signs or symptoms concerning for critical limb ischemia or acute limb ischemia.

(Answer B - Revascularization therapy via endovascular therapy, endarterectomy, or bypass surgery)

For patients with claudication, revascularization can be considered when patients have life-limiting symptoms after trialing exercise rehabilitation and goal-directed medical therapy.1 Unlike patients with stable claudication, patients with critical limb ischemia should undergo revascularization as first line treatment.2 Despite this patient's significant CTA findings, she does not have any signs or symptoms (such as inaudible doppler pulses, no loss of sensory function or muscle weakness, no rest pain, tissue loss, or ulcerations) that would be concerning of critical limb ischemia. Therefore, this patient should be trialed on GDMT prior to considering revascularization. This is especially true considering her age and the longevity of revascularization techniques.

(Answer C - Therapeutic anticoagulation with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC))

The most recent guidelines published by the ACC/AHA in 2016 recommend against the use of anticoagulation in patients with PAD.2 This was a Class III: Harm recommendation. In the WAVE (Warfarin Antiplatelet Vascular Evaluation) trial, there was no difference in cardiovascular ischemic events in patients with antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation versus antiplatelet therapy alone.2 There was an increased bleeding risk in the former group.2 However, more recent trials such as COMPASS (Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies) and VOYAGER PAD (Vascular Outcomes Study of ASA [acetylsalicylic acid] Along with Rivaroxaban in Endovascular or Surgical Limb Revascularization for PAD) have demonstrated benefit of low dose rivaroxaban (2.5mg twice daily) in addition to aspirin in reducing major adverse cardiovascular events and adverse limb events.6,7 However, the addition of rivaroxaban did increase the risk of major bleeding by 1%. This therapy has not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.6

(Answer D - B-complex vitamin supplementation to lower homocysteine levels)

The most recent guidelines published by the ACC/AHA in 2016 recommend against the use of b-complex vitamin supplementation in patients with PAD.2 This was a Class III: No Benefit recommendation. Patients with PAD have demonstrated increased plasma homocysteine levels. B-complex supplementation has been proven to lower homocysteine levels, however, there is no evidence that b-complex vitamin supplementation improves clinical outcomes for patients with PAD.2

(Answer E - Empiric therapy with pentoxifylline)

The most recent guidelines published by the ACC/AHA in 2016 recommend against the use of pentoxifylline in patients with PAD.2 This was a Class III: No Benefit recommendation. Pentoxifylline's mechanism of action is to decrease blood viscosity by increasing red blood cell membrane flexibility.8 Although pentoxifylline is generally well tolerated, it did not show benefit over placebo in the primary endpoint of maximal walking distance.2

References

- Kullo IJ, Rooke TW. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Peripheral artery disease. N Engl J Med 2016;374:861–71.

- Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:e71–e126.

- Kithcart AP, Beckman JA. ACC/AHA versus ESC guidelines for diagnosis and management of peripheral artery disease: JACC guideline comparison. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72: 2789–2801.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 1996;348:1329–39.

- Hiatt WR, Fowkes FGR, Heizer G, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in symptomatic peripheral artery disease. N Engl J Med 2017;376:32–40.

- Firnhaber JM, Powell CS. Lower extremity peripheral artery disease: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician 2019;99:362–69.

- Creager MA. A bon VOYAGER for peripheral artery disease. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2047–48.

- Porter JM, Cutler BS, Lee BY, et al. Pentoxifylline efficacy in the treatment of intermittent claudication: multicenter controlled double-blind trial with objective assessment of chronic occlusive arterial disease patients. Am Heart J 1982;104:66–72.