A 62-year-old female with a medical history of asthma who presents to the emergency department (ED) with acute substernal/epigastric pain that radiates to her mid-back. The pain started abruptly while at rest and has gotten progressively worse on transport to the ED. Pain is associated with nausea, sweating and dyspnea. Patient reports that she has never experienced pain like this before.

On physical exam blood pressure is 169/91 mmHg in the right arm and 165/89 mmHg, pulse is 70 bpm, temperature is 97.7°F and SpO2 is 100% on room air. The patient is in no acute distress, heart rate and rhythm are regular, no murmurs appreciated. Pulses are 2+ throughout with trace bilateral pedal edema. Lungs are clear to auscultation with normal pulmonary effort. Patient endorses tenderness to palpation over lower sternum.

Laboratory work including troponin, basic chemistry and complete blood count are within normal limits. Electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrates lateral T wave inversions. Chest x-ray shows no acute cardiopulmonary disease.

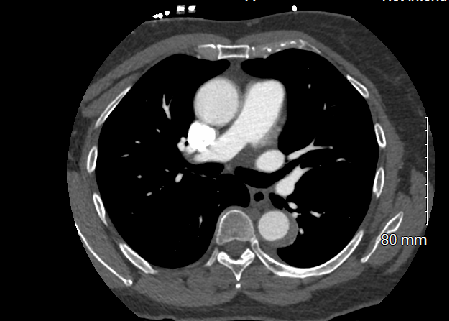

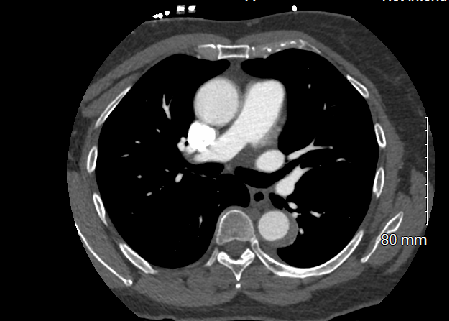

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) demonstrates a crescentic, high density thickening of the wall of the thoracic aorta beginning in the proximal descending thoracic aorta at the aortic isthmus and extending roughly to the diaphragmatic hiatus (Figure 1). The ascending aorta and aortic arch do not appear to be involved. The proximal great vessels appear to be unremarkable, and the thoracic aorta is normal in caliber.

Figure 1

Figure 1: CTA chest demonstrating a crescentic high density thickening of the wall of the descending thoracic aorta.

Figure 1: CTA chest demonstrating a crescentic high density thickening of the wall of the descending thoracic aorta.

Figure 1: CTA chest demonstrating a crescentic high density thickening of the wall of the descending thoracic aorta.

The correct answer is: D. Medical management

Acute aortic dissection (AAD) first occurs when there is an intimal tear within the aorta. Pulsatile blood flow then applies pressure to this tear, propagating a dissection of the media and producing a false lumen along the aortic wall. This dissection can spread distally, proximally, or both.1 The Sanford Classification system is most commonly used in diagnosis of such a phenomenon and distinguishes type A and type B AAD by whether the ascending aorta is involved. Type A does involve the ascending aorta while type B does not, with an entry point past the left subclavian artery.2 Further, type B AAD's are termed complicated if patients have or develop rupture, malperfusion syndromes, refractory pain or rapid aortic extension.1 These patients do require emergent endovascular or surgical repair. This patient's imaging is concerning for a type B AAD and she does not currently meet criteria for a complicated type B AAD; therefore, the patient can be treated conservatively through medical management (Answer D).

Initial medal therapy in these patients aims to simultaneously decrease the blood pressure and reduce the force of the left ventricle. Intravenous β-blockers are first line therapy and should be titrated to a systolic blood pressure between 100 to 120 mmHg and heart rate of <60, while also ensuring appropriate cerebral, coronary, and renal perfusion. If β-blockers are inadequate in lowering pressure, vasodilators, such as nitroprusside, can be added.3 Pain management, typically with morphine, is also necessary to counteract the catecholamine surge that further drives elevated pressures and heart rates during an AAD. Once patients are hemodynamically stable, they can be transitioned to oral β-blockers and antihypertensive agents before discharge home.3 Further, assessments of the aorta via imaging should be performed 1, 3, 9 and 12 months after diagnosis and every 6 to 12 months after the one-year mark has lapsed.3,4 The INSTEAD trial highlights the efficacy of such conservative treatment, as it demonstrated that medical management with blood pressure goal of ≤120/80 mmHg in comparison to an endovascular stent-grafting showed no significant differences at the two-year follow up in uncomplicated type B ADD.5

(Answer A) While TEE imaging has similar sensitivity and specificity to CTA, it is not typically ordered in hemodynamically stable patients with suspected acute aortic dissection.1 Further, as the CTA of the chest already demonstrated a type B aortic dissection, TEE would provide little to no added benefit to the management of this patient. While CTA of the chest is the preferred diagnostic imaging choice for hemodynamically stable patients with AAD, TEE imaging can be advantageous in the case of a patient who is hemodynamically unstable and critically ill, as it can be performed quickly and at beside. Further, TEE does not require contrast media.1

(Answer B) Emergent surgical repair of the aorta is not indicated in this setting, as this is an uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. In contrast, acute type A dissection is a surgical emergency as mortality rates are almost 20% 24 hours after initial presentation and continue to climb thereafter.6 Death in these patients typically occurs secondary to aortic rupture, stroke, visceral ischemia, cardiac tamponade, or circulatory failure.6 Data suggests that emergent open surgical repair is optimal for treating type A aortic dissection.7,8

(Answer C) In uncomplicated type B AAD, surveillance imaging of the aorta is recommended at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after diagnosis and every 6 to 12 months thereafter.3,4 This allows for close assessment for signs of aortic expansion, aneurysm formation and leakage.4 There is no indication for repeat CTA of the chest 1 day after presentation assuming the patient's pain improves and there are no signs of malperfusion.1

(Answer E) Again, thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) is not indicated in this setting, as this is an uncomplicated type B AAD. As discussed above, complicated type B AAD do require intervention. In this population, endovascular therapies are becoming the standard of care as they have superior outcomes compared to open approaches.1

References

- Tran TP, Khoynezhad A. Current management of type B aortic dissection. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2009;5:53-63.

- Lombardi JV, Hughes GC, Appoo JJ, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) reporting standards for type B aortic dissections. J Vasc Surg 2020;71:723-47.

- Tsai TT, Nienaber CA, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes. Circulation 2005;112:3802-13.

- Erbel R, Alfonso F, Boileau C, et al. Diagnosis and management of aortic dissection. Eur Heart J 2001;22:1642-81.

- Nienaber CA, Rousseau H, Eggebrecht H, et al. Randomized comparison of strategies for type B aortic dissection: the INvestigation of STEent Graft in Aortic Dissection (INSTEAD) trial. J Vasc Surg 2010;51:1321-2.

- Nienaber CA, Eagle KA. Aortic dissection: new frontiers in diagnosis and management: Part I: from etiology to diagnostic strategies. Circulation 2003;108:628-35.

- Liu D, Luo H, Lin S, Zhao L, Qiao C. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of thoracic endovascular aortic repair with open surgical repair and optimal medical therapy for acute type B aortic dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2020;83:53-61.

- Mehta RH, Suzuki T, Hagan PG, et al. Predicting death in patients with acute type A aortic dissection. Circulation 2002;105:200-6.