A 74-year-old woman with a known history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) presents to the office for worsening shortness of breath and lightheadedness.

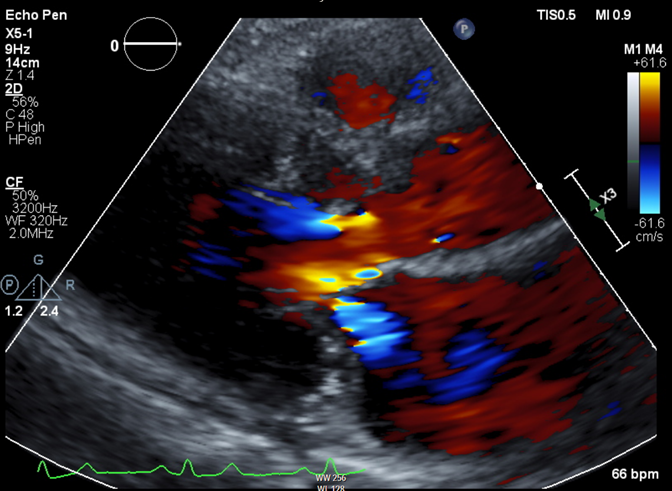

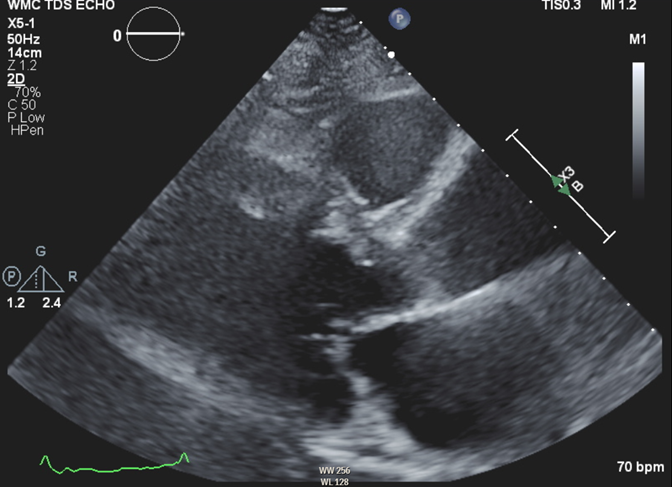

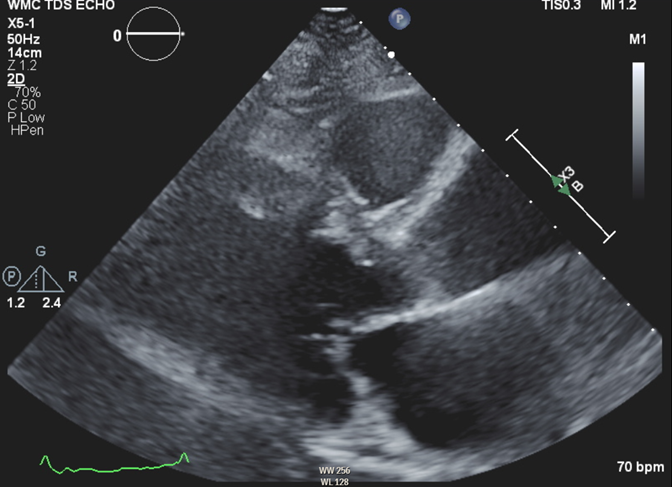

Her vital signs include heart rate (HR) 56 bpm, blood pressure (BP) 118/72 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation 99% on room air. Physical examination reveals unremarkable S1 and S2 with a grade 1/6 systolic ejection murmur, lung examination reveals no crackles, and there is no lower extremity edema. Echocardiography is notable for maximal basal septal thickness 2 cm, with systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve leading to moderate posteriorly directed mitral regurgitation (Figure 1). At rest, Doppler gradient through the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) is 25 mm Hg. The gradient through the LVOT increases to 130 mm Hg with Valsalva maneuver. A 48-hour telemetric monitor demonstrates a few short runs of supraventricular tachycardia but no atrial fibrillation or ventricular arrhythmias (VAs).

Figure 1

She has been maintained on beta-blocker and calcium channel blocker therapy with metoprolol succinate 50 mg twice daily and extended-release verapamil 120 mg in the morning and 80 mg in the evening. Despite her medications, she notes worsening shortness of breath and lightheadedness while walking only a few steps. Electrocardiography (ECG) in the office shows sinus rhythm at a rate of 56 bpm and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) with repolarization abnormality consistent with HCM; her ECG findings are unchanged from prior.

The correct answer is: B. Alcohol septal ablation.

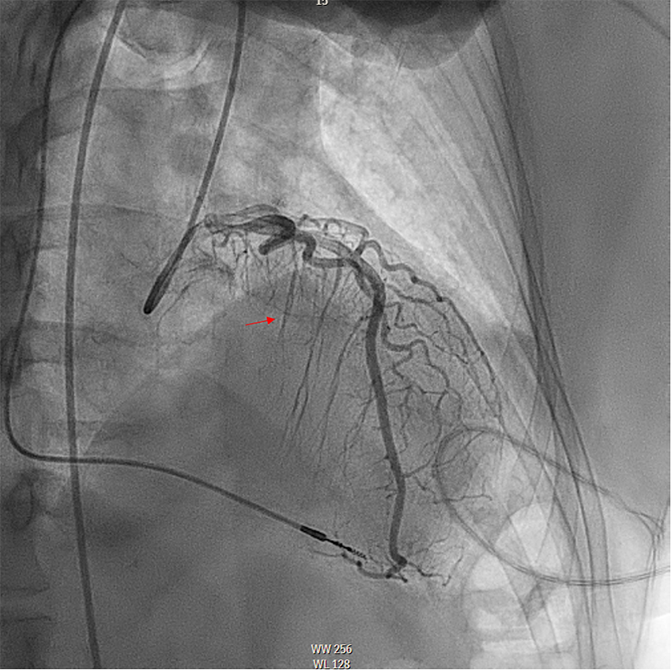

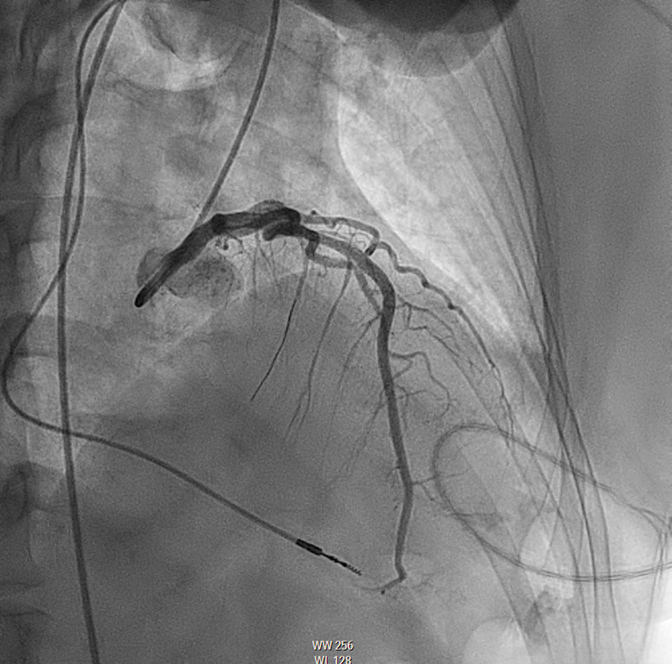

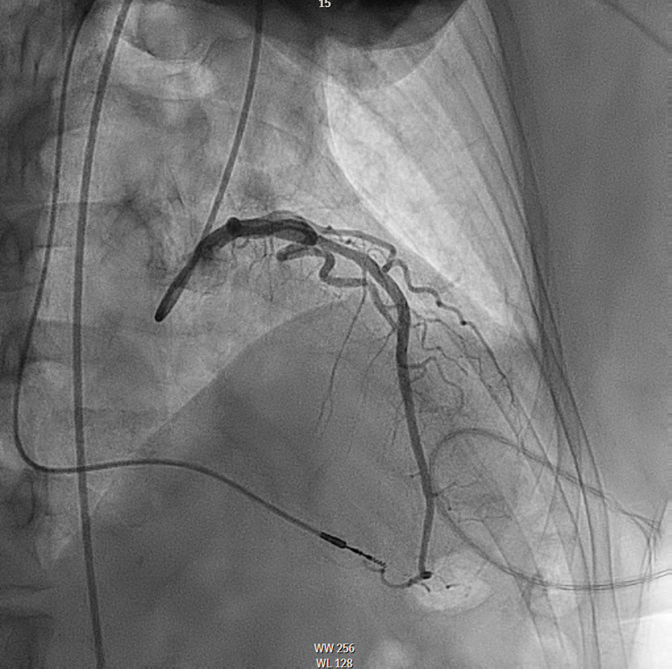

This patient met the criteria for septal reduction therapy (SRT) as a Class I indication based on continued New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III symptoms and lightheadedness on exertion, appropriate anatomy (septal thickness >1.5 cm), and outflow tract gradient >50 mm Hg despite optimal medical therapies. She decided to proceed with alcohol septal ablation (ASA) after a thorough discussion of both options. Based on myocardial contrast echocardiography, the second septal perforator (Figure 2) was wired (Figure 3) and ablated with 2 cc of 98% ethanol. Final angiography showed ablation of this perforator, with normal Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 3 flow in the left anterior descending artery (Figure 4). Postoperative ECG showed a new right bundle branch block (RBBB). There was no evidence of high-grade heart block during the procedure or postoperatively, and she was discharged on postprocedure day 4. Echocardiography was performed at the 1-month mark after ASA because she demonstrated akinesis of the basal septal wall and thickness of 1.5 cm, with no evidence of LVOT obstruction at rest.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Six months postablation, she felt well, NYHA class I (asymptomatic). She no longer had any dyspnea on exertion or lightheadedness. She was able to exercise without limitation. Echocardiography at follow-up showed a normalization of basal septal thickness to 0.9 cm without SAM or LVOT obstruction (Figure 5).

Figure 5

According to the 2020 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients With HCM, it is a Class I indication for patients with obstructive physiology and basal thickness >1.5 cm on maximum medical therapy to undergo SRT.1 SRT is comprised of either surgical myectomy or ASA. This patient was on 50 mg of extended-release metoprolol BID and verapamil BID, yet was still extremely symptomatic, making SRT with ASA the most appropriate choice (answer choice B). Recent observational comparisons between ASA and septal myectomy have shown similar outcomes in functional status improvement and survival, as long as they are performed at high-volume centers of excellence.2,3 The choice of ASA or septal myectomy is dependent on the patient's anatomy, age, and comorbidities; baseline conduction abnormalities; and the experience and volume of the treating institution and operator. In general, older patients, such as this one, and those with focal septal hypertrophy (as opposed to massive hypertrophy or gradients) favor ASA, especially if there is a baseline RBBB. Patients with pre-existent pacemaker or defibrillator are also good candidates, as the higher incidence of conduction abnormalities after ASA is thereby mitigated. In contrast, younger patients, those without comorbidities, and those with massive hypertrophy or gradients are typically better served by myectomy. Patients with baseline left bundle branch block are also better served by myectomy, given the risk of heart block if they develop RBBB at the time of ASA.

Placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD; answer choice A) would be an incorrect choice in this case. This patient did not have high-risk features of HCM that would warrant an ICD. She did not have any evidence of VAs on monitoring, massive LVH >3 cm, recurrent unexplained syncope, apical aneurysm, or left ventricular systolic dysfunction.1

Initiation of furosemide (answer choice C) would not be the correct choice in a patient without signs of volume overload, especially when there is obstructive physiology. Although she certainly had dyspnea, her lung examination was unremarkable and she was saturating well on room air, with no edema. The use of diuretics in patients with HCM may decrease preload and worsen LVOT obstruction. This might precipitate syncope in a patient who is already exhibiting lightheadedness.

This patient was on sufficiently high doses of beta-blocker and calcium channel blocker therapy. Notably, her HR was 56 bmp and BP was within normal limits. Therefore, uptitration of her medications (answer choice D) would be difficult in this setting and may contribute to worsening dyspnea through impaired chronotropy.

Educational grant support provided by: Bristol Myers Squib

To visit the course page for the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Accelerating Guideline-Driven Care grant, click here.

References

- Ommen S, Mital S, Burke M, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:3022-55.

- Sorajja P, Ommen SR, Holmes DR Jr, et al. Survival after alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2012;126:2374-80.

- Steggerda RC, Damman K, Balt JC, Liebregts M, ten Berg JM, van den Berg MP. Periprocedural complications and long-term outcome after alcohol septal ablation versus surgical myectomy in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a single-center experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:1227-34.