Pediatric Syncope: Simple vs. Sinister

A 12-year-old girl with a history of loss of consciousness presents. The loss of consciousness occurred on a warm summer day while she was standing in line for a roller coaster ride. She recalls feeling lightheaded, sweaty, and nauseated before seeing black. According to her parents, she was unconscious for approximately 30 sec and spontaneously regained consciousness with no injury, incontinence, or shaking of her limbs. The event occurred at 11:30 a.m.; at 8 a.m., she had drunk 10 oz (295 mL) of apple juice and ate a donut for breakfast. She has no history of syncope or significant medical problems. A thorough cardiac family history identifies none of the following: congenital heart defects, myocardial infarctions at a young age (<50 years), cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, or sudden unexplained or cardiac death. Her mother fainted a few times as a teenager.

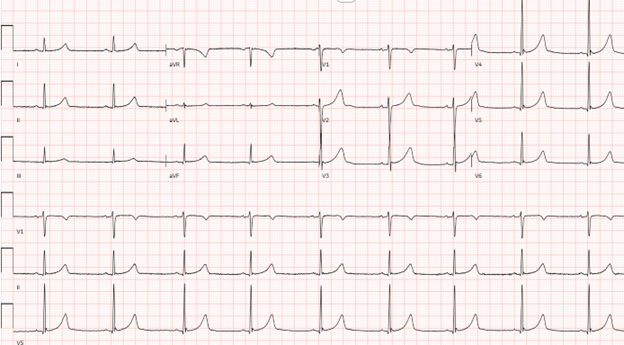

The patient's vital signs and physical examination findings are unremarkable. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is obtained (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Which one of the following next steps in management and evaluation is most appropriate?

Show Answer

The correct answer is: C. No further investigation.

The Class 1 recommendations from the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) for the evaluation of syncope include a detailed history of the chief condition, physical examination, family history, and 12-lead ECG.1 In this case, none of these findings indicated a concerning cardiac etiology and instead suggested a high likelihood that this patient had vasovagal syncope.1-7 Vasovagal syncope is described as a sudden, transient loss of consciousness and postural tone (usually <2 min) with spontaneous recovery. It typically occurs when a person is in an upright position and is preceded with prodromal symptoms of diaphoresis, warmth, nausea, and pallor.3 The phenomenon of prodromal symptoms leading to transient lightheadedness but without syncope is referred to as vasovagal nearsyncope.

A diagnosis of vasovagal syncope is often apparent with minimal testing such as an ECG, as in this case. Deferring further testing is therefore appropriate. Specifically, an echocardiogram is not indicated unless there are remarkable ECG findings, a family history suggestive of early causes of sudden cardiac arrest or electrophysiologic pathology, a family history suggestive of a cardiomyopathy, exertional syncope, or unexplained postexertional syncope.8 A Holter recording is not indicated without evidence of underlying cardiac pathology or suggestion of an arrhythmia by history. An invasive electrophysiology study would never be part of an initial evaluation.8,9 Therefore, answer choices A, B, D, and E are incorrect choices.

The differential diagnosis of syncope primarily includes cardiac, neurologic, and psychiatric etiologies. The cardiac evaluation provides guidance to patients, families, and other medical care providers. Focused questions in the history of present illness can help establish or exclude a cardiac etiology. The latter can be formatted as an electronic health record checklist allowing efficient documentation. The history should include a description of symptoms at the onset (prodrome) before loss of consciousness, the event (at the onset and during loss of consciousness), and the recovery.

Questions examining the prodrome should include whether the event occurred while at rest, during exercise, or after exercise. If occurring after exercise, the duration of delay following exercise should be established. Syncope at rest is far more likely to be benign than is syncope with exercise. In a series of 334 young patients with syncope, only midexertional syncope was associated with a cardiac diagnosis.5 Triggers other than exercise such as pain, loud noises, urination, or emotional stress should also be included in the description. For example, a loud alarm trigger may increase the suspicion of long QT syndrome.8 Body position (e.g., lying, sitting, standing, or changing position), appearance, and associated symptoms during the prodrome should be ascertained. Syncope occurring while lying is inconsistent with vasovagal syncope.3 Palpitations are a frequent prodrome of vasovagal syncope.3 However, palpitations as a first symptom without any other symptoms would suggest a possible arrhythmia. Chest pain during exertion followed by syncope would also prompt further evaluation to assess for a cardiac etiology.9 Confusion, visual changes (e.g., tunnel vision), tinnitus, and lightheadedness may also be prodromal symptoms in vasovagal syncope. Lightheadedness should be differentiated from vertigo if possible. The duration between the prodromal events and the onset of loss of consciousness is not diagnostic, as a short prodrome with minimal symptoms may be seen with vasovagal syncope.

After obtaining details of the prodrome before the loss of consciousness, the fall type (flaccid vs. tonic) should be determined. Although both types may be seen with vasovagal syncope, flaccidity is not typically seen with seizures. A description of the appearance during loss of consciousness such as seizure activity, injury, incontinence, tongue biting, and eyelid position will also help differentiate cardiac from neurologic causes of loss of consciousness. Short but not prolonged myoclonic activity may be seen with vasovagal syncope, incontinence may be seen with vasovagal syncope or seizures, and eyes being open suggests a neurologic cause. The duration of the loss of consciousness should be noted if there was a witness. With vasovagal syncope, the duration is typically <30 sec.

Finally, the history should also include details of recovery such as appearance, mental status, and time to return to baseline. Although vasovagal syncope is frequently followed by reports of fatigue and headache, a longer period of confusion or drowsiness suggests a neurologic event.

This case emphasizes the importance of simple, cost-effective methods of evaluating syncope. Once a diagnosis of vasovagal syncope is made and other diagnoses are excluded, management consists mainly of patient education. Reassurance should be given that there is not a significant cardiac pathology. The vasovagal reflex can be explained in layperson's terms to help patients avoid situations in which syncope may occur, such as standing for long periods. Patients should be counseled to lie down when the prodromal symptoms begin to avoid a dangerous fall or public embarrassment. Additionally, adequate hydration is essential; the appropriate volume of daily fluid intake may vary by patient. Liberal added sodium in the diet is also necessary for water retention. Syncope may be recurrent even with these interventions, in which case pharmacologic therapy (e.g., fludrocortisone) may be warranted. An extensive discussion of the pathophysiology and management of syncope is beyond the scope of this exercise and the reader is referred to the references provided.

References

- Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:e39-e110.

- Kakavand B. Dizziness, syncope, and autonomic dysfunction in children. Progress in Pediatric Cardiology 2022;65:[ePub ahead of print].

- Yeom JS, Woo HO. Pediatric syncope: pearls and pitfalls in history taking. Clin Exp Pediatr 2023;66:88-97.

- Zavala R, Metais B, Tuckfield L, DelVecchio M, Aronoff S. Pediatric syncope: a systematic review. Pediatr Emerg Care 2020;36:442-5.

- Turan O, Marshall T, Runciman M, Schaffer M, von Alvensleben J, Collins KK. Assessment of paediatric exertional or peri-exertional syncope: does the story matter? Cardiol Young 2023;33:2190-5.

- Winder MM, Marietta J, Kerr LM, et al. Reducing unnecessary diagnostic testing in pediatric syncope: a quality improvement initiative. Pediatr Cardiol 2021;42:942-50.

- Liao Y, Du J. Pathophysiology and individualized management of vasovagal syncope and postural tachycardia syndrome in children and adolescents: an update. Neurosci Bull 2020;36:667-81.

- Sharma N, Cortez D, Disori K, Imundo JR, Beck M. A review of long QT syndrome: everything a hospitalist should know. Hosp Pediatr 2020;10:369-75.

- Campbell RM, Douglas PS, Eidem BW, Lai WW, Lopez L, Sachdeva R. ACC/AAP/AHA/ASE/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/SOPE 2014 appropriate use criteria for initial transthoracic echocardiography in outpatient pediatric cardiology: a report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Pediatric Echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:2039-60.