This case highlights the role of an EP study to identify AF triggers, such as SVT, to target the arrhythmogenesis of AF. Up to 39% of young patients with AF have inducible SVT (e.g., atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia [AVNRT] or AV re-entrant tachycardia) during an EP study, and targeted SVT ablation in these cases has been associated with decreased AF recurrence.1-4 An EP study revealing SVT degenerating into AF allows for targeting the initiating AF trigger and being able to spare patients left-sided trans-septal catheterizations and bilateral PVIs. The fast atrial activation with AVNRT provides the arrhythmic substrate to degenerate into AF.5 Given the high prevalence of SVT and high rates of arrhythmia-free success following targeted ablation in young adults, an SVT evaluation and ablation in young patients with AF carries a class 2a recommendation in the 2024 Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Expert Consensus Statement on Arrhythmias in the Athlete.6 Additionally, clinicians should inquire about stimulant and performance-enhancing drug use in young athletes presenting with tachyarrhythmias because drugs such as cocaine, amphetamines, marijuana, and ecstasy may increase the risk of atrial arrhythmias.6

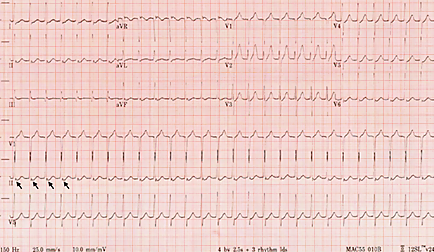

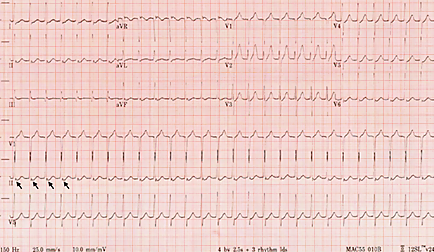

The SVT shown in this case presentation is a narrow complex tachycardia with a short RP interval (note the pseudo S wave in the inferior leads shown by the black arrows in Image 4). After the initial presentation, this patient underwent an EP study, which had findings of dual-pathway physiology including the presence of slow pathway activity and maneuvers confirming an SVT mechanism diagnosis of AVNRT. He underwent successful slow pathway modification and had no AF recurrence on implantable loop recorder monitoring after the ablation. Successful elimination of the triggering SVT arrhythmia resolved all future recurrences of AF. He was once again being considered for military deployments and was returned to his full occupational duties.

Image 4

ECG performed during episode of SVT highlighting the short RP tachycardia (black arrows).

ECG = electrocardiogram; SVT = supraventricular tachycardia.

PVI with the primary objective of restoring and maintaining sinus rhythm to eliminate the need for long-term anticoagulation would not be the correct answer choice because PVI catheter ablation does not target the underlying triggering arrhythmia. Further, the risk of stroke following ablation is not reduced after successful ablation without continued medical therapy for stroke prevention.6-8

Genetic testing is recommended in young adult athletes with AF, a strong family history of arrhythmia, or imaging and ECG findings that would raise suspicions for channelopathies or cardiomyopathy.9-10 The titin (TTN), sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 5 (SCN5A), and potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member 5 (KCNA5) genes have been identified as being strongly associated with AF; the recommendation to refer for genetic counseling and testing is made given the potential for sudden cardiac arrest with these allelic variants.6

This patient had a low risk of stroke on the basis of validated risk-score systems. Currently, minimal data exist regarding the safety of briefly withholding anticoagulation to allow for participation in contact sports or sports with the risk of traumatic injury.6 Additionally, LAAO has not been studied in athletes, would not be the highest priority in addressing this patient's symptoms, and would not be indicated in light of his low presenting stroke risk.6

References

- El Assaad I, Hammond BH, Kost LD, et al. Management and outcomes of atrial fibrillation in 241 healthy children and young adults: revisiting "lone" atrial fibrillation-a multi-institutional PACES collaborative study. Heart Rhythm. 2021;18(11):1815-1822. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2021.07.066

- Sciarra L, Rebecchi M, De Ruvo E, et al. How many atrial fibrillation ablation candidates have an underlying supraventricular tachycardia previously unknown? Efficacy of isolated triggering arrhythmia ablation. Europace. 2010;12(12):1707-1712. doi:10.1093/europace/euq327

- Strieper MJ, Frias P, Fischbach P, Costello L, Campbell RM. Catheter ablation of primary supraventricular tachycardia substrate presenting as atrial fibrillation in adolescents. Congenit Heart Dis. 2010;5(5):465-469. doi:10.1111/j.1747-0803.2009.00368.x

- Furst ML, Saarel EV, Hussein AA, et al. Medical and interventional outcomes in pediatric lone atrial fibrillation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4(5):638-648. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2018.02.014

- Weiss R, Knight BP, Bahu M, et al. Long-term follow-up after radiofrequency ablation of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in patients with tachycardia-induced atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80(12):1609-1610. doi:10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00753-4

- Lampert R, Chung EH, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2024 HRS expert consensus statement on arrhythmias in the athlete: evaluation, treatment, and return to play. Heart Rhythm. 2024;21(10):e151-e252. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.05.018

- Marrouche NF, Brachmann J, Andresen D, et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(5):417-427. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1707855

- Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Deshmukh AJ, et al. Patterns of anticoagulation use and cardioembolic risk after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(11):e002597. Published 2015 Nov 5. doi:10.1161/JAHA.115.002597

- Giustetto C, Cerrato N, Gribaudo E, et al. Atrial fibrillation in a large population with Brugada electrocardiographic pattern: prevalence, management, and correlation with prognosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(2):259-265. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.10.043

- Johnson JN, Tester DJ, Perry J, Salisbury BA, Reed CR, Ackerman MJ. Prevalence of early-onset atrial fibrillation in congenital long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5(5):704-709. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.02.007