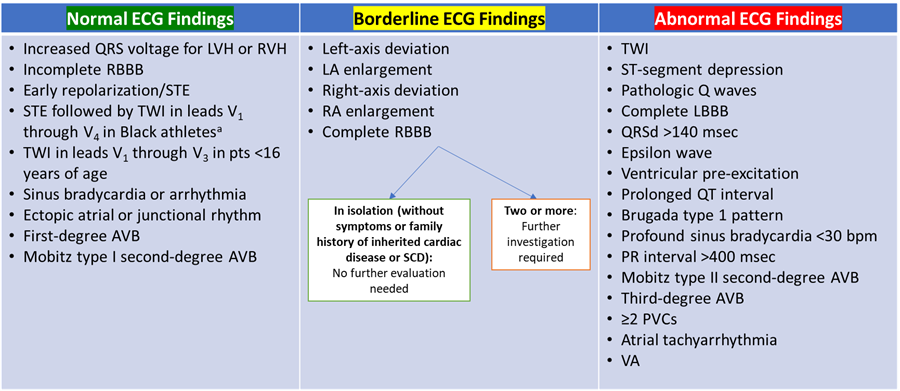

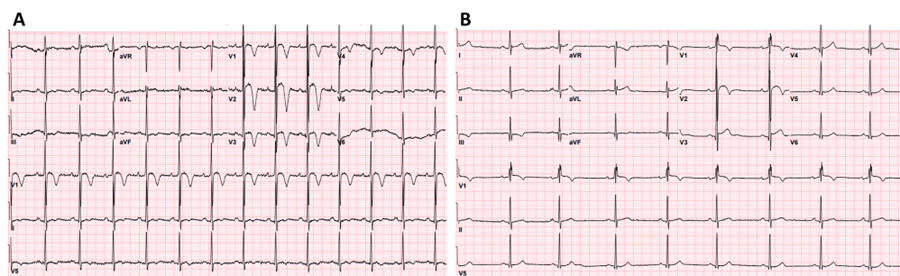

Syncope during exercise always warrants further cardiac testing (Figure 1). The deeply inverted/biphasic T waves in V2 and V3 raise concern for Wellens ECG pattern, thus inpatient coronary angiography should be pursued to rule out significant coronary artery stenosis before alternative etiologies are explored. When evaluating athletes with syncope, a careful history is paramount. Recent guidelines have provided guidance for evaluating syncope in a young athlete by stratifying based on relationship to exercise. After the history confirms syncope during exercise, an ECG, echocardiogram, and exercise stress test are recommended (Class 1) for diagnostic workup, though given this patient's age (which places him close to a Master's athlete demographic conveying a higher risk of ischemic etiology) and clinical presentation, cardiac catheterization should also be performed. If strong clinical suspicion for cardiac etiology persists despite negative testing results, then advanced testing (e.g., computed tomography angiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging [cMRI], and ambulatory arrythmia monitoring) should be pursued.1

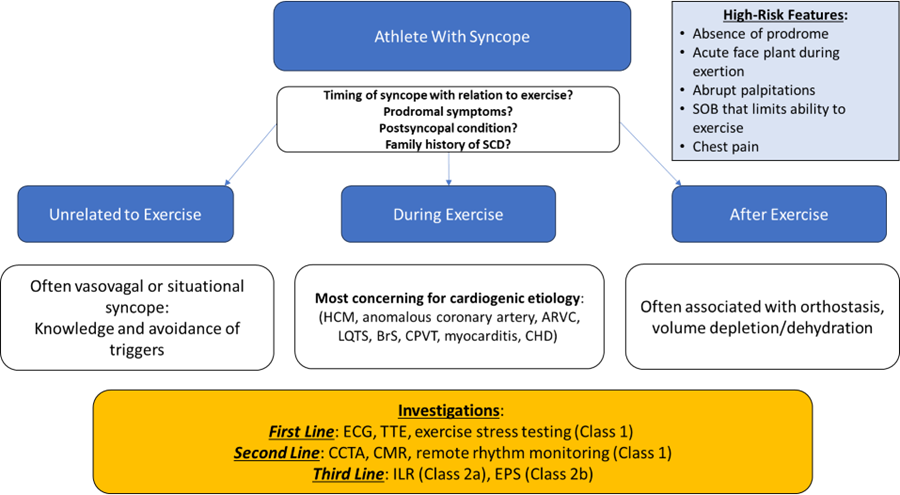

Figure 1: Algorithm for an Athlete With Syncope

Modified from Lampert R, Chung EH, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2024 HRS expert consensus statement on arrhythmias in the athlete: evaluation, treatment, and return to play. Heart Rhythm. 2024;21(10):e151-e252. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.05.018

ARVC = arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; BrS = Brugada syndrome; CCTA = coronary computed tomography angiography; CHD = congenital heart disease; CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; CPVT = catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; ECG = electrocardiogram; EPS = electrophysiological study; HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ILR = implantable loop recorder; LQTS = long QT syndrome; SCD = sudden cardiac death; SOB = shortness of breath; TTE = transthoracic echocardiogram.

A prior study looked at the incidence of syncope in athletes undergoing preparticipation screening and identified 6.2% of individuals in a cohort of 7,568 who had experienced a syncopal episode in the previous 5 years. In those with syncope, most of their events were unrelated to exercise (86.7%), and only six events (1.3% of all episodes) took place during exercise. Of those six patients, one was diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, another was diagnosed with RV outflow tract tachycardia, and the other four demonstrated a positive response to tilt table testing.2 In a more recent retrospective study of college athletes, exercise-related syncope was identified in nine individuals who received varying levels of cardiac testing. Of those nine individuals, one was diagnosed with a cardiac abnormality (right coronary artery arising from the opposite sinus of Valsalva). The cause of syncope for the other patients was attributed to exercise-associated collapse. During this time, no athletes with syncope later experienced SCD.3

Taken together, these findings add to a growing body of evidence that athletes who experience syncope during exercise may have a lower likelihood of having underlying cardiovascular pathology than previously hypothesized, though it is important to note that this data is in younger patients than the one discussed here, who is on the cusp of being considered a Masters-aged athlete. Furthermore, the high ratio of diagnostic testing to cardiac diagnoses is not trivial and adds a layer of complexity to an already difficult clinical question in sports cardiology. Although recent guideline statements have been published, the optimal evaluation for exercise-related syncope in young athletes is not known. Nonetheless, the cardiac conditions found in the aforementioned studies (albeit rare, although a not-trivial percentage of those were found to have exertional syncope) can be implicated in SCD and, if detected, may be lifesaving, including channelopathies, anomalous coronary arteries, and cardiomyopathies.4

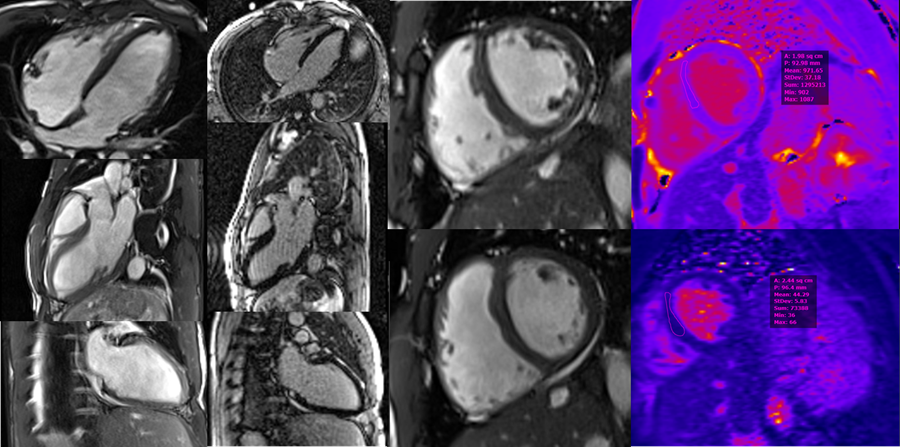

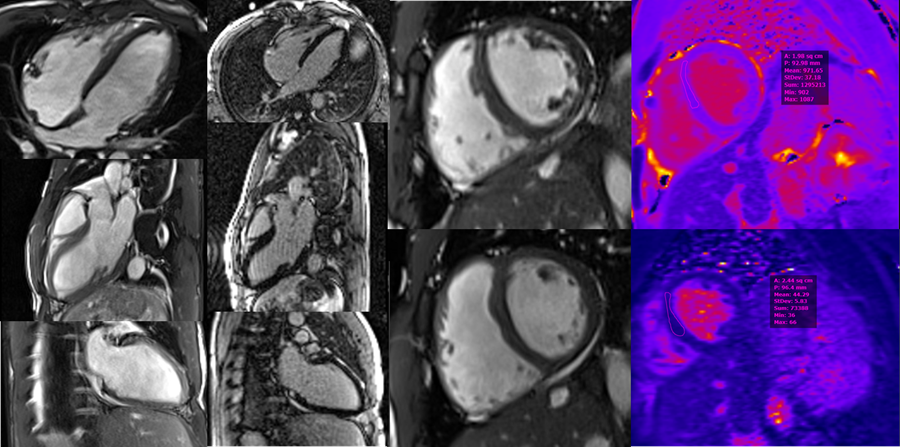

For this patient, an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction code was canceled after a point-of-care echocardiogram had findings of no segmental WMAs. A diagnostic left heart catheterization demonstrated normal coronary arteries without anomalous origin. He was monitored in the cardiac intensive care unit for further evaluation of syncope. Neither ventricular arrythmia (VA) nor atrioventricular block was seen on 5 days of telemetry monitoring. As his laboratory study values improved, cMRI performed 36 hours later had findings of normal LV size and function, upper limit of normal RV size and function (RV ejection fraction 57%) with no scar on late gadolinium enhancement, and normal T1 (972 msec) and T2 (44 msec) mapping times consistent with athlete's heart (Image 2). TWI resolved in leads V3 and V4, although they persisted in leads V1 and V2 (Image 3). A maximal intensity exercise stress test had unremarkable findings, including no evidence of VA. His syncope was attributed to extreme volume depletion and ECG changes from baseline abnormalities exaggerated by rhabdomyolysis. He was discharged with recommendations for adequate hydration and further remote rhythm monitoring. After no abnormalities were found on remote rhythm monitoring and shared decision-making, he returned to exercise without restrictions.

Image 2

CMR images demonstrating normal LV size (LVEDVi 94 mL/m2) and function (LVEF 53%). ULN RV size (RVEDVi 111 mL/m2) and normal RV systolic function (RVEF 57%). Normal T1 (972 msec) and T2 (44 msec) mapping times. No evidence of scar on LGE imaging. Most consistent with athlete's heart.

CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; LV = left ventricular; LVEDVi = left ventricular end-diastolic volume index; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; RV = right ventricular; RVEDVi = right ventricular end-diastolic volume index; RVEF = right ventricular ejection fraction; ULN = upper limit of normal.

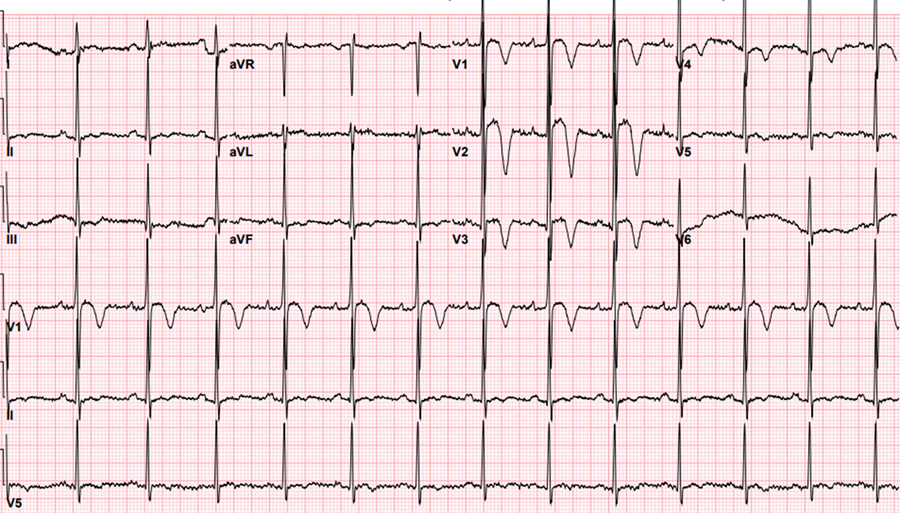

Image 3

ECGs on arrival to the ED showing J-point elevation and convex (domed) STE followed by TWI in leads V1 through V4 (panel A) and on hospital discharge 5 days later with partial resolution (panel B).

ECG = electrocardiogram; ED = emergency department; STE = ST-segment elevation; TWI = T-wave inversions.

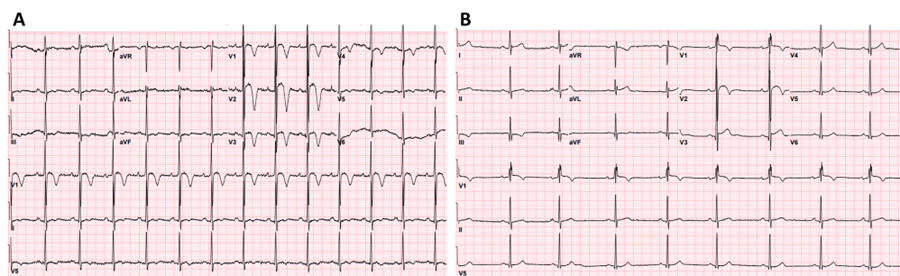

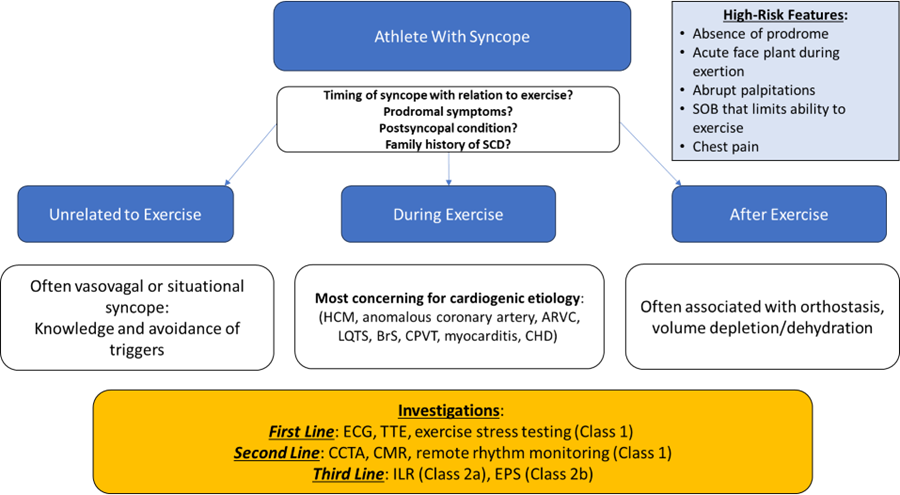

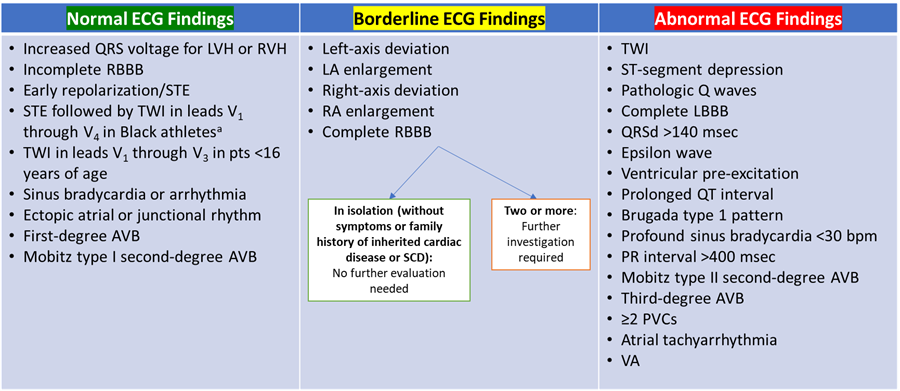

Hydration and observation are incorrect choices because syncope during exercise with concerning ECG findings always warrants further workup. In the context of syncope, this athlete's ECG findings are concerning but in an asymptomatic athlete may have been considered similar to the athlete repolarization variant, although there might have been more prominent changes due to concomitant electrolyte derangements on presentation. Interpretation of normal athlete ECG findings in the context of the international criteria pertain to asymptomatic athletes only (Figure 2).5

Figure 2: ECG Screening in Athletes

Modified from Sharma S, Drezner JA, Baggish A, et al. International recommendations for electrocardiographic interpretation in athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(8):1057-1075. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.015

a The validity of using race in the context of determining pathogenicity has been under debate.

AVB = atrioventricular block; ECG = electrocardiogram; LA = left atrial; LBBB = left bundle branch block; LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy; pts = patients; PVC = premature ventricular contraction; QRSd = QRS duration; RA = right atrial; RBBB = right bundle branch block; RVH = right ventricular hypertrophy; SCD = sudden cardiac death; STE = ST-segment elevation; TWI = T-wave inversions; VA = ventricular arrhythmia.

Discharge with outpatient cardiology follow-up is an incorrect choice. Admission for cardiac testing and further observation would be advised given his exertional syncope presentation, elevated CPK level, and acute kidney injury.

References

- Lampert R, Chung EH, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2024 HRS expert consensus statement on arrhythmias in the athlete: evaluation, treatment, and return to play. Heart Rhythm. 2024;21(10):e151-e252. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.05.018

- Finocchiaro G, Westaby J, Sheppard MN, Papadakis M, Sharma S. Sudden cardiac death in young athletes: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83(2):350-370. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.10.032

- Gier C, Shapero K, Lynch M, et al. Exertional syncope in college varsity athletes. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2023;9(8 Pt 2):1596-1597. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2023.04.004

- Petek BJ, Churchill TW, Moulson N, et al. Sudden cardiac death in national collegiate athletic association athletes: a 20-year study. Circulation. 2024;149(2):80-90. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.065908

- Sharma S, Drezner JA, Baggish A, et al. International recommendations for electrocardiographic interpretation in athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(8):1057-1075. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.015