Family History Mystery: Is Cardiac Blood Thicker Than Water?

A 10-year-old girl with a history of a spontaneously closed secundum atrial septal defect presents for clearance prior to being started on medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. She has no history of chest pain, exercise intolerance, dizziness, syncope, dyspnea, palpitations, or irregular heartbeat. Her mother reports that the paternal grandfather (PGF) experienced sudden cardiac death (SCD) 3 months ago, with his autopsy demonstrating ventricular hypertrophy and 25% stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. No other family members have been diagnosed with cardiac conditions.

The patient's physical examination reveals a grade 2/6 vibratory systolic ejection murmur consistent with a Still murmur.

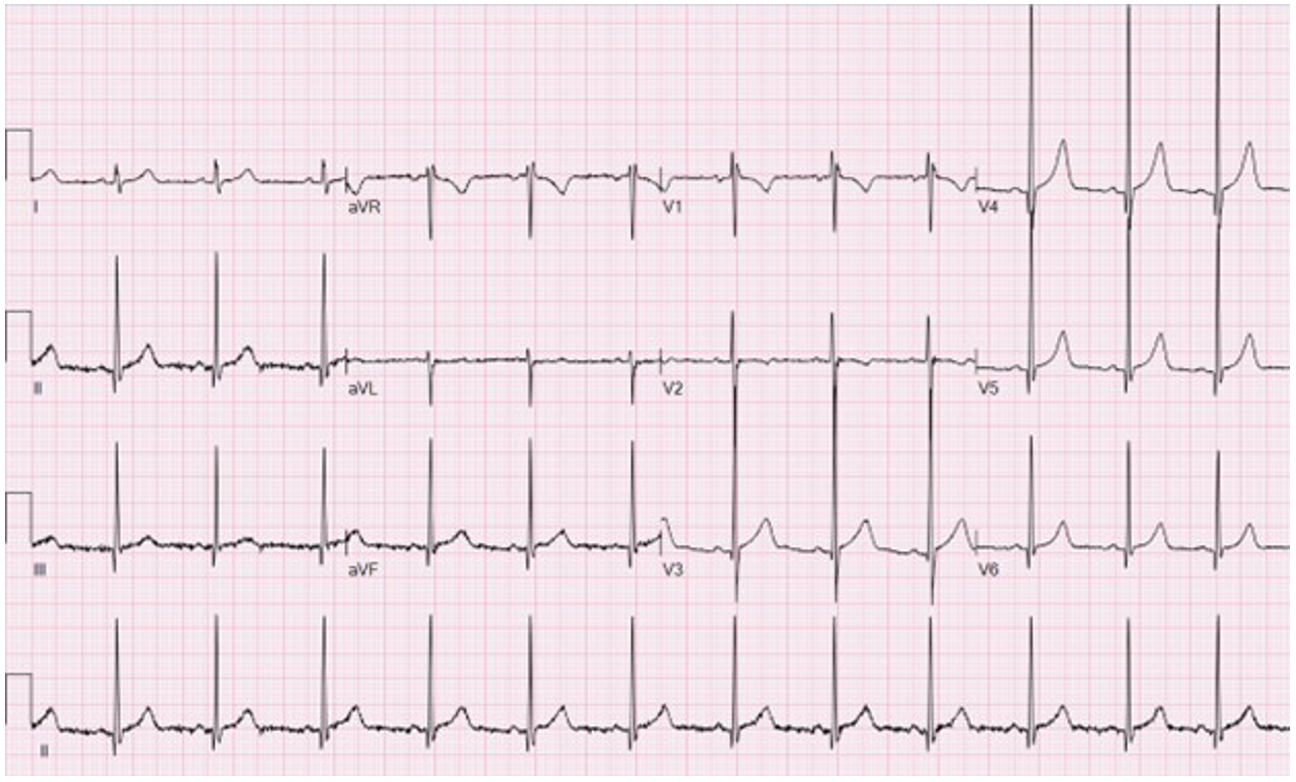

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is obtained (Image 1). An echocardiogram demonstrates normal chamber sizes, normal biventricular systolic function, and normal left ventricular wall thickness and diastolic function indexes.

Image 1

Which one of the following is the best next step in her management?

Show Answer

The correct answer is: C. Pursue postmortem genetic testing on her PGF.

This patient's PGF was reported to have a thick heart on autopsy, raising the possibility that he was an index case of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). The yield of genetic testing is highest when initiated in an individual with the phenotype. Therefore, pursuing postmortem genetic testing on her PGF would be the best next step.

HCM is a relatively common condition, with a reported incidence of 1:200 to 1:500 individuals.1-3 Cardiologists are therefore likely to encounter scenarios in which patients with common reasons for referral are also found to have a family history suggestive of cardiomyopathy. The latter underscores the value of a detailed multigenerational family history (at least three generations).1 This history should include inquiring not only about family members with an accepted cardiomyopathy diagnosis, but also about members with heart failure, thickened or enlarged hearts, or sudden death of unclear etiology.

Genetic testing is an important part of caring for patients with HCM. Ideally, families should be provided with genetic counseling in the pre- and post-test setting to aid risk stratification in HCM.1,4 Genetic causes of HCM include sarcomeric, metabolic, and syndromic etiologies, with most due to pathogenic variants in one of the sarcomere genes.5,6 HCM is typically inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. The most common sarcomeric genes implicated in HCM encode myosin binding protein C (MYBPC3) and beta-myosin heavy chain (MHY7). The yield of genetic testing is up to 60% in people with HCM and a significant (HCM-phenotype) family history. However, not all patients with phenotype-positive HCM will have a pathogenic genetic variant. Patients who have the HCM phenotype and uncertain genetic variants should be re-evaluated periodically (depending on clinical findings) with specific re-evaluation of the genetic variant every 2-3 years.1

Postmortem genetic testing refers to genetic testing on a sample from a deceased individual affected by the disease of interest.7 Barriers to completing postmortem genetic testing include lack of appropriate specimens, difficulty obtaining family consent, and insurance coverage limitations. However, postmortem genetic testing can be impactful for a decedent's family. Identification of a likely pathogenic or pathogenic variant responsible for HCM in the decedent has the potential for targeted cascade testing (testing first-degree relatives of the affected individual for the same genetic variant). In absence of other cardiac symptoms, family members testing negative for the pathogenic variant could be discharged from lifelong cardiac surveillance.

In this case, the family history revealed a PGF with SCD and a thick heart on autopsy, raising suspicion of primary HCM. In older patients, ventricular hypertrophy can arise secondary to abnormal loading conditions (e.g., hypertension, aortic stenosis, coarctation of the aorta). Determining whether the hypertrophy is primary or secondary can therefore be difficult. Genetic testing may be helpful in making this distinction. Due to the wide variety of contributors to sudden death, the yield of postmortem genetic testing may be up to 30% and can act as a molecular complement to traditional autopsy.7 In this case, if postmortem genetic testing identified a pathogenic variant in the index case (this patient's PGF), then testing the father for the identified variant could directly determine the patient's risk of having the pathogenic variant (50% if the father is positive for autosomal dominant HCM vs. equivalent to the general population if the father is negative). If postmortem genetic testing is not possible, clinical screening (ECG/echocardiogram) of the decedent's first-degree relatives is recommended. Genetic testing should then be performed in those with findings suggestive of cardiomyopathy. A negative genetic test result in the index case (PGF in this case) still does not rule out the possibility of an inherited HCM. There is no consensus on surveillance monitoring for patients in whom the family history is suspicious but the genetic testing results are nondiagnostic. Periodic clinical screening is reasonable in those cases.

On the basis of this patient's echocardiogram and ECG findings, she did not have evidence of phenotype-positive HCM. However, discharging her from cardiology care without considering the uncertainty about the underlying genotype and future risk of HCM would be inappropriate given her family history.

The possibility of phenotype-negative, genotype-positive HCM may cause concern regarding exercise participation and risk of SCD. Recent consensus guidelines emphasize a shared decision-making (SDM) approach in evaluating patients with phenotype- or genotype-positive HCM for sports participation.8,9 Even in individuals with phenotype-positive HCM, it is deemed reasonable to consider competitive sports participation after SDM due to the lack of robust evidence that the risk of SCD is higher than in the general population.

In this asymptomatic patient with reassuring test results, further diagnostic testing such as a cardiac MRI would not be necessary. A cardiac MRI is useful in cases in which there is diagnostic uncertainty (e.g., borderline echocardiogram findings or concern for infiltrative cardiomyopathy) and in patients with known HCM to delineate the etiology of any outflow tract obstruction and/or to stratify the risk of SCD.1,2,10

In summary, this case illustrates the diagnostic thought process dealing with a relatively frequent occurrence of a normal patient with a family history suggestive of HCM. The approach to family screening may differ on the basis of the available information about the decedent, the disease of concern (e.g., other forms of cardiomyopathy, other causes of SCD), and the yield of genetic testing. In cases of missing information or uncertainty about the patient's risk of SCD, continuing clinical monitoring is reasonable and warranted.

References

- Writing Committee Members, Ommen SR, Ho CY, et al. 2024 AHA/ACC/AMSSM/HRS/PACES/SCMR guideline for the management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83(23):2324-2405. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2024.02.014

- Fadl SA, Revels JW, Rezai Gharai L, et al. Cardiac MRI of Hereditary Cardiomyopathy. Radiographics. 2022;42(3):625-643. doi:10.1148/rg.210147

- McKenna WJ, Judge DP. Epidemiology of the inherited cardiomyopathies. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(1):22-36. doi:10.1038/s41569-020-0428-2

- Hershberger RE, Givertz MM, Ho CY, et al. Genetic evaluation of cardiomyopathy-a Heart Failure Society of America practice guideline. J Card Fail. 2018;24(5):281-302. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.03.004

- Hathaway J, Heliö K, Saarinen I, et al. Diagnostic yield of genetic testing in a heterogeneous cohort of 1376 HCM patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21(1):126. Published 2021 Mar 5. doi:10.1186/s12872-021-01927-5

- Miron A, Lafreniere-Roula M, Steve Fan CP, et al. A validated model for sudden cardiac death risk prediction in pediatric hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2020;142(3):217-229. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047235

- Deignan JL, De Castro M, Horner VL, et al. Points to consider in the practice of postmortem genetic testing: A statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2023;25(5):100017. doi:10.1016/j.gim.2023.100017

- Paldino A, Rossi M, Dal Ferro M, et al. Sport and exercise in genotype positive (+) phenotype negative (-) individuals: current dilemmas and future perspectives. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023;30(9):871-883. doi:10.1093/eurjpc/zwad079

- Kim JH, Baggish AL, Levine BD, et al. Clinical considerations for competitive sports participation for athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025;85(10):1059-1108. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2024.12.025

- Abraham MR, Abraham TP. Role of imaging in the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2024;212S:S14-S32. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2023.10.081