A 57-year-old man with a history of HIV infection presented with new-onset angina. He reported two episodes of prolonged (>20 minutes) substernal chest discomfort with associated diaphoresis. His only medical history was chronic HIV infection managed with tenofovir/emtricitabine, darunavir, and ritonavir, with stable CD4 counts of approximately 500 cells/mcL and undetectable viral loads (0 copies/mL). His lipids had been well controlled while on HAART therapy since the 1990s. He had no other cardiac risk factors.

His blood pressure was 126/81mmHg, heart rate was 67 beats per minute, and BMI was 38. His physical exam was unremarkable. His cardiac troponin-T was elevated at 0.05 ng/ml (ULN 0.01 ng/ml) and his ECG showed sinus rhythm with 1 mm of horizontal ST segment depression in V3-V5.

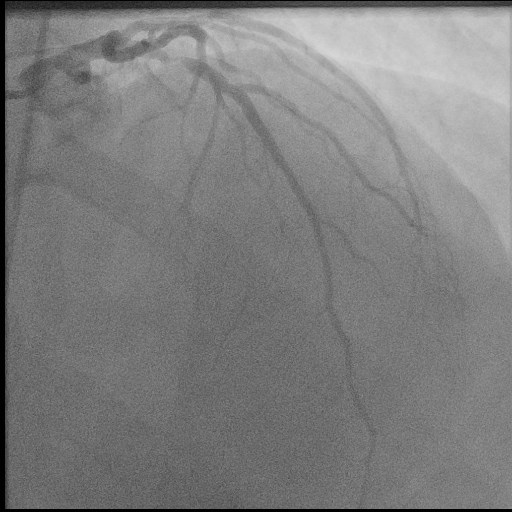

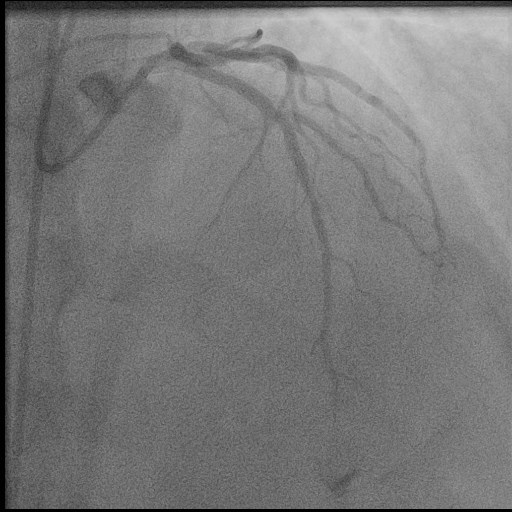

He was initiated on medical therapy for NSTE-ACS and coronary angiography was performed which demonstrated the culprit 95% proximal LAD stenosis (Figure 1). Successful percutaneous coronary intervention was performed with 0% residual stenosis and TIMI III flow (Figure 2).

The correct answer is: D. None of the above

Advancing age has correlated with an increased risk of developing coronary artery disease. As demonstrated in the Framingham Heart Study, males 40-69 years of age had a nearly 50% lifetime risk of developing coronary heart disease1. HIV infection has also been associated with accelerated atherosclerosis, more commonly presenting at a younger age with single-vessel disease, and an increased risk of acute myocardial infarction2,3. Mechanisms may include endothelial dysfunction related to increased expression of adhesion molecules (E-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1) and inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha and IL-6)4. Protease inhibitor therapy has been associated with increased atherosclerosis as it can result upon dyslipidemia and insulin resistance. The DAD study group performed a retrospective analysis of a prospective observational study cohort and found an increase in myocardial infarction in HIV patients on protease inhibitor therapy, but no significant association with NRTI therapy5.

References

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Beiser A, and Levy D. Lifetime risk of developing coronary heart disease. Lancet, 353 (1999), pp. 89-92.

- Freiberg MS et al. HIV Infection and the Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):614-622.

- Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, and Grinspoon SK. Increased Acute Myocardial Infarction Rates and Cardiovascular Risk Factors among Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2506–2512, 2007.

- Cardiovascular Abnormalities in HIV-Infected Individuals. (2015). In D. Mann, D. Zipes, P. Libby, R. Bonow, & E. Braunwald (Eds.), Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine (10th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 1624-1635). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

- DAD Study Group; Friis-Moller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA, et al. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:1723–35.