Antithrombotic Therapy in an Elderly Patient With Atrial Fibrillation

An 81-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes presents to the office for evaluation after a recent mechanical fall. She denies hitting her head or loss of consciousness. She denies any fatigue, palpitations, or dyspnea on exertion. She is an active person and lives independently while performing all activities of daily living. On exam, she is 63 inches, weighs 61 kilograms, blood pressure 135/85 mm Hg, and her rhythm is irregularly irregular with rate in the 80s.

Routine electrocardiogram performed in the office reveals a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. Recent laboratory results included a creatinine clearance of 55 mL/min and normal liver function tests.

Her medical history is notable for an upper gastrointestinal bleed from a duodenal ulcer 10 years ago. She ambulates with a cane and has had no previous falls. The patient wishes to avoid frequent lab testing and does not want medical procedures.

Which of the following is the next step in anticoagulation management?

Show Answer

The correct answer is: B. Start full dose rivaroxaban 20 mg QD.

Atrial fibrillation is a common arrhythmia encountered in the elderly population with a prevalence of around 9.0% in those greater than 80 years of age.1,2 It is associated with a five-fold increase in risk of ischemic stroke with more than 75% of strokes occurring in individuals greater than 65 years of age.3 In addition, morbidity and mortality rates following atrial fibrillation-related strokes, which are more severe and likely to recur, are higher in the elderly.4

Warfarin has been shown to be under-prescribed in older patients. Clinician concerns about falls, dementia, and intracranial hemorrhage are cited as reasons for suboptimal use.5 In the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) cohort, warfarin was used in approximately 60% of patients aged 65-84 and only 35% of patients older than 85, despite the fact that net clinical benefit with warfarin increases with age.6, 7 Previous studies have shown that episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, falling, old age should not dictate anticoagulation, rather it should be based on stroke risk, and fears of the risk of bleeding are often exaggerated and sometimes unfounded.8

This patient has a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 5 (hypertension, age >75 [2 pts], diabetes, female), which places her in the high-risk category with a 6.7% stroke risk per year.9 In the elderly, the risk of bleeding with anticoagulation therapy is a major concern. The HAS-BLED score is one of the best validated scoring systems to evaluate the risk of bleeding. This patient has a score of 1 (age >65), placing her in moderate risk with an estimate of 1.02 bleeds per 100 patient years.10, 11

The 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines for atrial fibrillation emphasize the importance of shared decision making in the choice for anticoagulation.12 Shared decision involves patient participation in active assessment of risks and benefits of treatment options for stroke prevention and determines the best course of action taking into account the patient's values, goals, and preferences.13

After discussion, the patient should be started on chronic anticoagulation therapy with rivaroxaban 20 mg daily. Rivaroxaban offers increased convenience for this patient with a fixed dose, predicable pharmacologic profile, rapid onset, and few drug interactions.

In the Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared With Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF) trial, once-daily rivaroxaban 20 mg (15 mg once-daily in patients with creatinine clearance 15-50 mL/min) was non-inferior to warfarin in preventing stroke/systemic embolism (SEE), and there was no significant difference in the risk of major bleeding and all-cause mortality. There were far fewer intracranial hemorrhages (0.8% vs. 1.2%) but more GI bleeds (3.2% vs. 2.2%) in the rivaroxaban group compared to the warfarin group.14

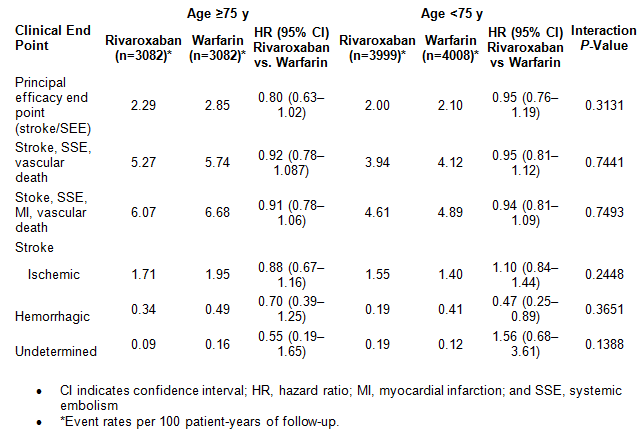

A recently published pre-specified secondary analysis of the ROCKET AF study compared the efficacy and safety results between warfarin and rivaroxaban in patients aged ≥75 versus <75 years.15 There were 6,229 patients older than 75 years of age with more than two stroke risk factors randomized to warfarin or rivaroxaban. During 10,866 patient-years of exposure, stroke/SEE were more common in patients ≥75 years of age than in those <75 (2.57% versus 2.05%/100 patient-years; P=0.0068). Stroke/SEE rates were consistent among older (2.29% rivaroxaban versus 2.85% warfarin per 100 patient-years; hazard ratio [HR] =0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.63–1.02) and younger patients (2.00% versus 2.10%/100 patient-years; HR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.76–1.19; interaction P=0.313). Prevention of ischemic stroke was comparable among older and younger patients.15

Major bleeding was more frequent in the ≥75 versus <75 years age group (4.63% versus 2.74%/100 patient-years; P<0.0001). But there was no significant difference in rates of major bleeding among patients on rivaroxaban as compared to warfarin in either age group (≥75 years: 4.86% rivaroxaban versus 4.40% warfarin per 100 patient-years; HR=1.11; 95% CI, 0.92–1.34; <75 years: 2.69% versus 2.79%/100 patient-years; HR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.78–1.19; interaction P=0.336). Also, there was no significant interaction between age and relative safety between rivaroxaban and warfarin.

|

Option A is not the correct answer because, using a shared decision making model, warfarin therapy is incompatible with the patient's preference for avoiding frequent lab draws and medical procedures such as cardioversion.

Option C is not the best option because the dose of rivaroxaban should not be reduced just based on the age of a patient. Rivaroxaban should be dose adjusted for moderate to severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance of 15-50 mL/min) and avoided for creatinine clearance of <15 mL/min.

Option D is not the best option because, as discussed above, the patient has a significant stroke risk and would benefit from anticoagulation. Although the risk of bleeding is increased in the elderly, this patient has a six-fold higher risk of stroke as compared to major bleeding based on current risk scores.

Efficacy End Points According to Age and Treatment Allocation15

References

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014;129:e28-e292.

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 2001;285:2370-5.

- Chen RL, Balami JS, Esiri MM, Chen LK, Buchan AM. Ischemic stroke in the elderly: an overview of evidence. Nat Rev Neurol 2010;6:256-65.

- Hylek EM, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. Effect of intensity of oral anticoagulation on stroke severity and mortality in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1019-26.

- Ogilvie IM, Newton N, Welner SA, Cowell W, Lip GY. Underuse of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am J Med 2010;123:638-45.e4.

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Borowsky LH, Phillips KA, Selby JV, Singer DE. Warfarin use among ambulatory patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: the anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:927-34.

- Singer DE, Chang Y, Fang MC, et al. Should patient characteristics influence target anticoagulation intensity for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation?: the ATRIA study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009;2:297-304.

- Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A. Anticoagulant-related bleeding in older persons with atrial fibrillation: physicians' fears often unfounded. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1580-6.

- Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 2010;137:263-72.

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010;138:1093-100.

- Lip GY, Frison L, Halperin JL, Lane DA. Comparative validation of a novel risk score for predicting bleeding risk in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation: the HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal Renal/Liver Function, Stroke, Bleeding History or Predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs/Alcohol Concomitantly) score. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:173-80.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014 March. [Epub ahead of print].

- Seaburg L, Hess EP, Coylewright M, Ting HH, McLeod CJ, Montori VM. Shared decision making in atrial fibrillation: where we are and where we should be going. Circulation 2014;129:704-10.

- Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:883-91.

- Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Wojdyla DM, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Rivaroxaban Compared With Warfarin Among Elderly Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation in the Rivaroxaban Once Daily, Oral, Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared With Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF). Circulation 2014;130:138-46.