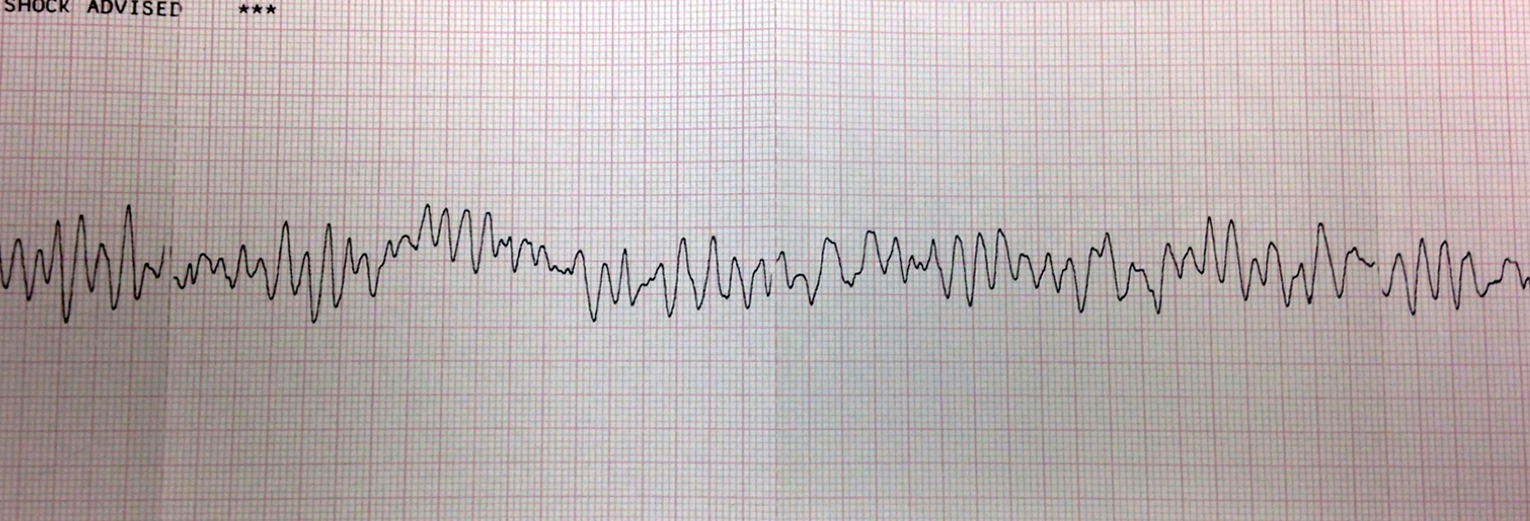

A 24-year-old female with no medical history was running when she suddenly collapsed. A bystander witnessed the event and immediately contacted emergency medical services who arrived in approximately three minutes. An automated external defibrillator is placed on the patient and the following rhythm is seen (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Initial rhythm strip in the field showing ventricular fibrillation

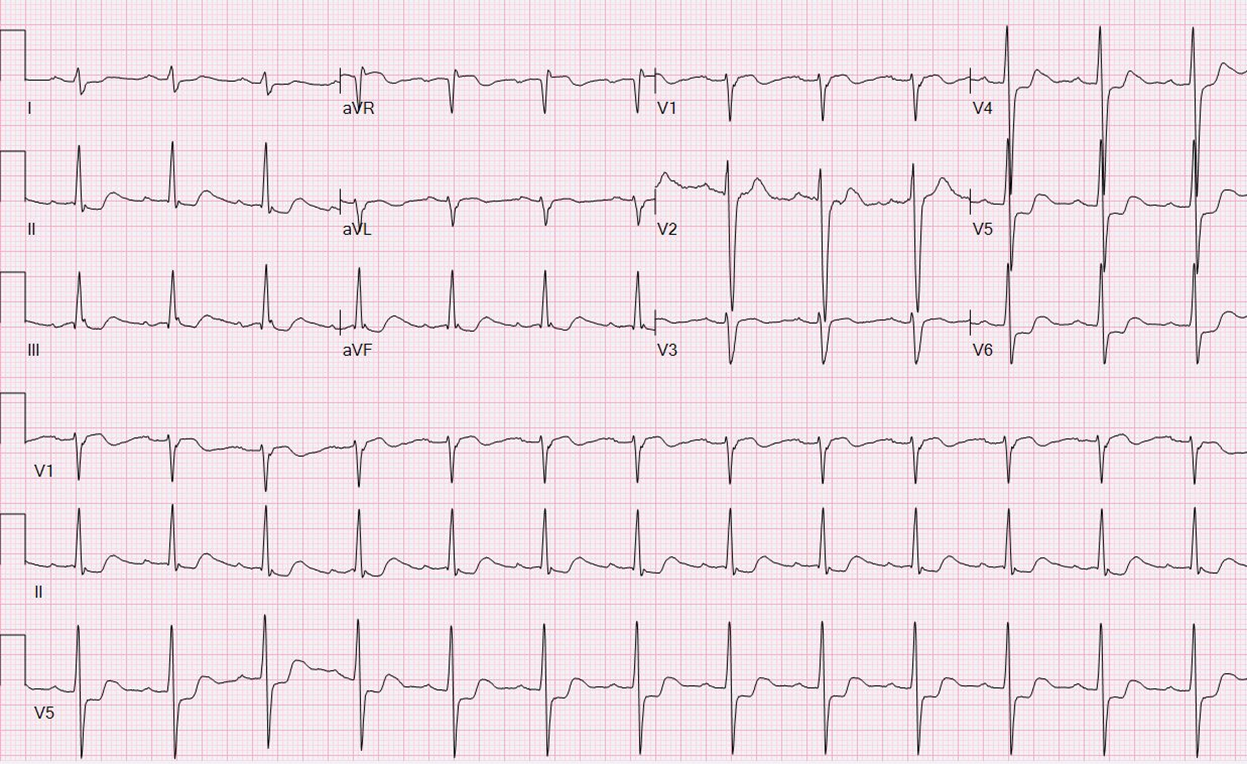

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation efforts are promptly started and an appropriate shock is delivered. The patient is rapidly transferred to the emergency department. After achieving hemodynamic stability, the patient's baseline electrocardiogram is obtained (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Initial 12-lead EKG showing sinus rhythm with a nonspecific intraventricular conduction block and ST and T wave abnormalities concerning for ischemia

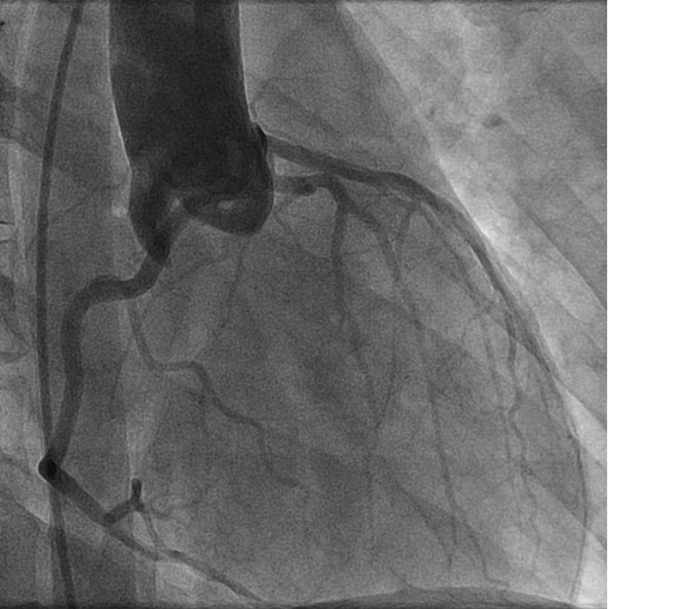

Cardiology is promptly consulted for further evaluation including consideration for therapeutic hypothermia. The patient was brought to the cardiac catheterization lab for coronary angiography. Engagement of the left coronary ostium from the left coronary cusp proves challenging, warranting consideration of an anomalous left coronary artery. The following aortogram is obtained to help determine the origin of the left coronary artery (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Aortogram showing a suspected anomalous left main coronary artery with an intraarterial course and anterior "dot" sign

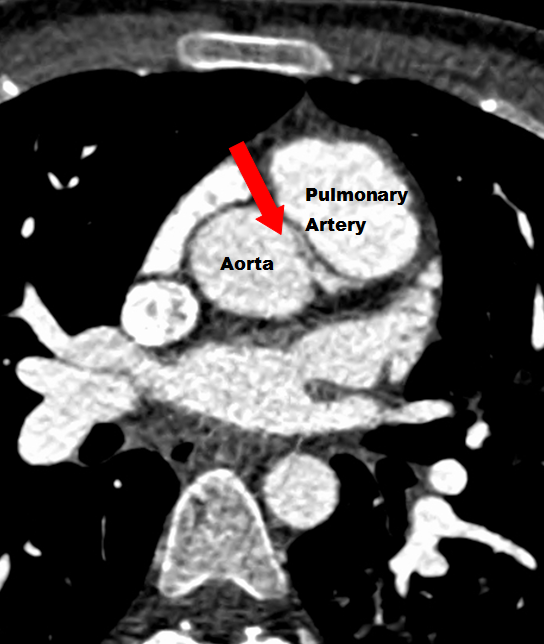

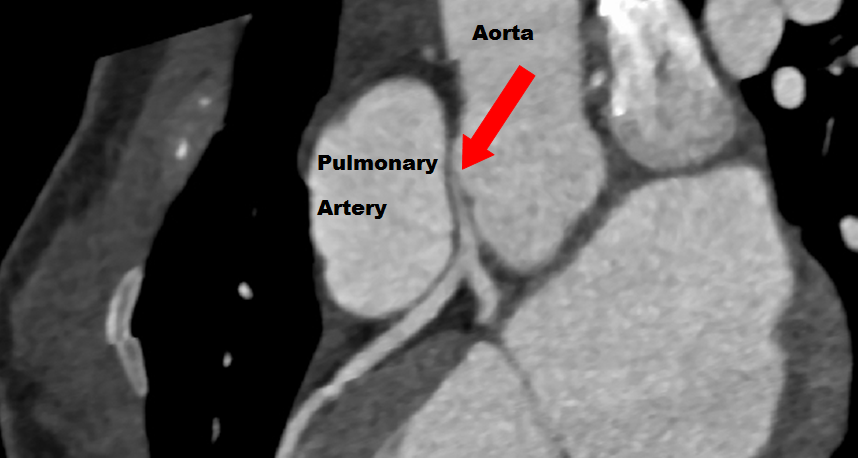

An anomalous left coronary artery with an inter-arterial course is suspected based on the presence of an anterior "dot" sign. Subsequent coronary computed tomography angiogramconfirm an anomalous left main coronary artery with a narrowed ostium and course between the aorta and pulmonary artery (Figures 4-5).

Figure 4: Coronary computed tomography angiogram showing an anomalous left main coronary artery with a narrowed ostium and coursing between the aorta and pulmonary artery

Figure 5: Coronary computed tomography angiogram showing an anomalous left main coronary artery with a narrowed ostium and coursing between the aorta and pulmonary artery

The patient is referred for surgical correction and undergoes a coronary unroofing procedure without complication.

The correct answer is: B. 3 months

Though estimated to occur in <1% of the population, anomalous coronary arteries are a well-described congenital malformation.1 Patients are predominantly asymptomatic until presenting with sudden collapse. This patient participated in sports throughout her lifetime including soccer, volleyball and running, and was training for a marathon when this event occurred. In young athletes, congenital anomalies of the wrong sinus are the second most common cause of sudden cardiac death (SCD), with speculation that coronaries with an inter-arterial course may become compressed between the aorta and pulmonary artery during periods of vigorous exercise.2 Long proximal portions of anomalous arteries also travel within the aortic wall, and aortic expansion during exercise may compress the intramural portion of the artery.3 Exercise has the effect of increasing oxygen consumption, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and end diastolic volume, potentially predisposing athletes to coronary ischemia.

Because of the low incidence of anomalous coronary vessels causing SCD and the lack of data validating proposed mechanisms, guidelines for management are not well defined.4 The most common corrective procedure involves excising, or "unroofing," the intramural segment of the anomalous vessel. Other procedures include creation of a new coronary ostium, coronary reimplantation, pulmonary artery translocation, and coronary artery bypass grafting. Without correction, it is recommended patients be excluded from all competitive sports. After correction; however, the evidence regarding participation in sports is ambiguous. The 2005 Bethesda Conference suggests that after successful operation, athletic competition is permitted, provided the patient has no evidence of ischemia, dysrhythmia, or ventricular dysfunction during maximal exercise testing.5 Waiting for a three month period post-correction has been the strategy of the Coronary Anomalies Program at Texas Children's Hospital, which has attempted to standardize evaluation and management of patients with coronary anomalies since 2012.3

References

- Kimbiris D, Iskandrian AS, Segal BL, Bemis CE. Anomalous aortic origin of coronary arteries. Circulation 1978;58:606-15.

- Maron BJ. Sudden death in young athletes. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1064-75.

- Mery CM, Lawrence SM, Krishnamurthy R, et al. Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery: toward a standardized approach. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;26:110-22.

- Brothers J, Gaynor JW, Paridon S, Lorber R, Jacobs M. Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery with an interarterial course: understanding current management strategies in children and young adults. Pediatr Cardiol 2009;30:911-21.

- Graham TP, Jr., Driscoll DJ, Gersony WM, Newburger JW, Rocchini A, Towbin JA. Task Force 2: congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:1326-33.