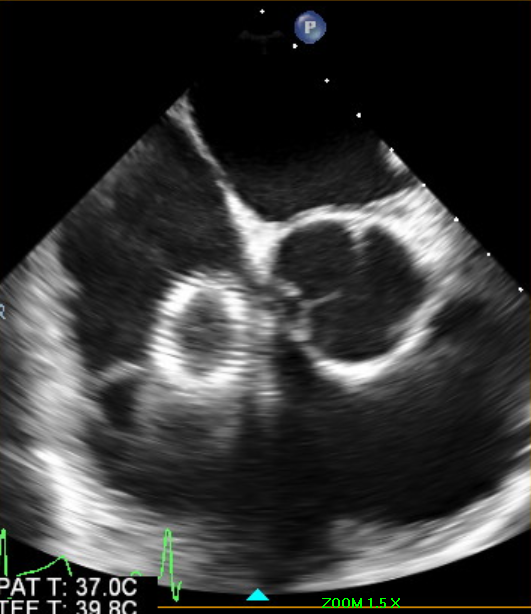

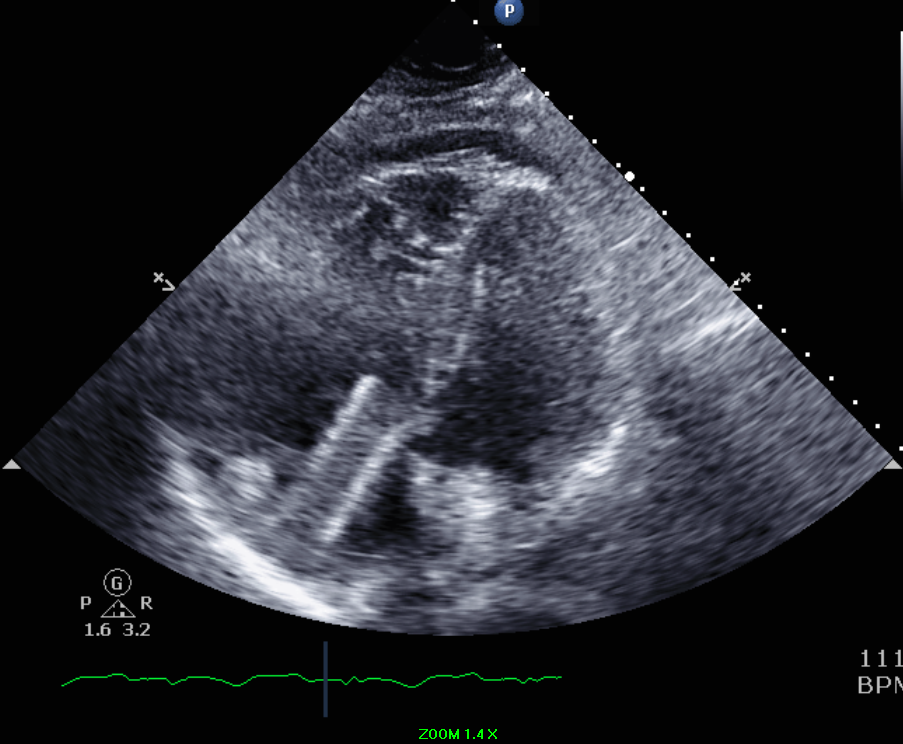

A 37-year-old obese male-to-female transgender patient with past medical history of venous insufficiency presented to the hospital with chest pain. The patient was in her usual state of health until 2 days prior to admission when she developed right-sided sudden onset chest pain radiating to the back and neck while walking up the stairs. Chest pain has been intermittent and positional and was brought on by upper body motion. Upon further questioning, the patient reported undergoing an elective left common iliac vein stent placement the day prior to her symptoms started for management of venous insufficiency. Upon arrival to the hospital, the patient was hemodynamically stable. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed that revealed a hyperechoic linear tubular structure seen in the right atrium measuring approximately 6 cm in length and crossing the tricuspid leaflet with impingement into the right ventricular septum (Figures 1-2). The findings were consistent with migration of the recently placed iliac vein stent.

Figure 1

Figure 2

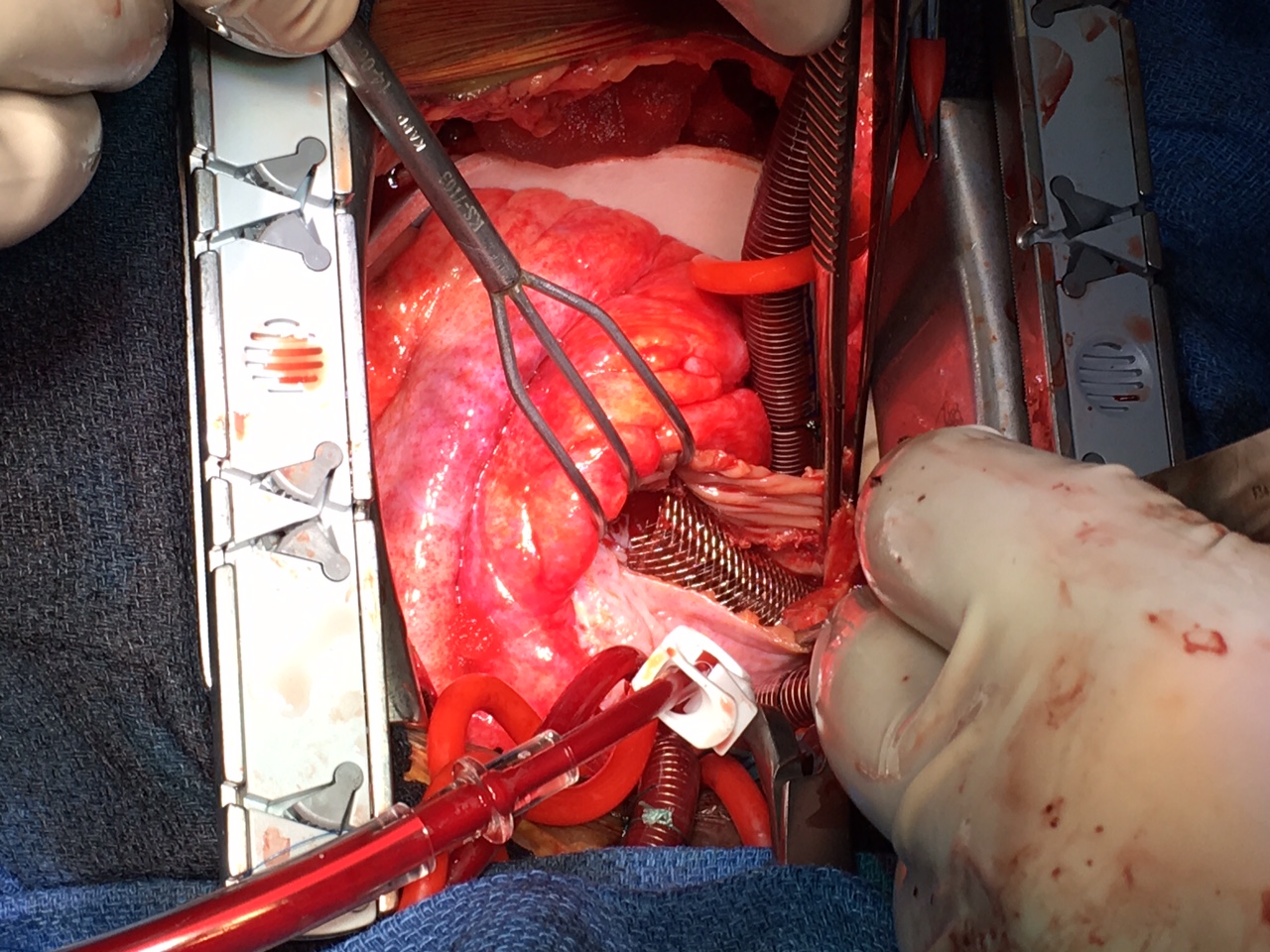

Two approaches for stent removal were considered: endovascular versus surgical retrieval. Given the location of the stent entangled in the tricuspid valve, endovascular retrieval was deemed higher risk for structural damage by the interventionalists. Subsequently, a successful complex surgical repair was performed, which included retrieval of the nitinol stent visualized protruding through the right atrial free wall. Furthermore, drainage of hemorrhagic pericardial effusion, atrial free wall repair, and tricuspid valve repair were performed (Figure 3). Postoperative course was uneventful. Follow-up evaluation in the clinic was also unremarkable.

Figure 3

The correct answer is: B. Skin pigmentation

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) has diverse clinical presentations ranging from mild to more severe disease.1 Its etiology can be nonthrombotic or thrombotic (for example, deep vein thrombosis), and its pathophysiological presentation may involve reflux and/or obstruction.1 CVI can be classified based on the Clinical-Etiology-Anatomy-Pathophysiology (CEAP) clinical severity (classes 1-6) that includes telangiectasia, varicose veins, edema, skin changes (pigmentation, eczema, lipodermatosclerosis), and venous ulceration, in order of severity.1-3 An estimated 23% of adults in United States have varicose veins, including 6% with more advanced chronic venous disease including skin changes and venous ulcers.2 2011 guidelines of Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum endorses various treatment options for varicose veins including compression therapy, sclerotherapy, endovenous thermal ablation or ligation/inversion stripping of superficial saphenous vein in the setting of saphenous vein incompetence.2

Deep venous obstruction has also been described as a cause of CVI. The iliocaval venous obstruction is highly prevalent, and it is most commonly seen in left iliac vein because it is always crossed by right iliac artery causing compression (May-Thurner Syndrome).4 Compression therapy is the treatment of choice for CVI; however, lately a benefit from interventional therapy has also been shown.5 Endovenous stenting has been recently adopted as an innovative treatment option for chronic venous obstruction, especially in the femoroiliocaval system.6-8 Furthermore, based on 2014 CIRSE Standards of Practice Guidelines on Iliocaval Stenting, patients with CEAP classes 3-6, which include edema, skin changes, and ulceration, should consider revascularization as a treatment option. Iliac vein stenting is recommended when the nonthrombotic lesion is stenosed more than 30%.1 Iliac vein stenting has been described as a safe and effective treatment for chronic benign venous obstruction, but there have been various complications reported, including stent thrombosis, venous perforation, and stent migration.9-10

Venous stent migration is a rare complication, with only 3% of incidence rate.9 Stents most commonly migrate to the right atrium or right ventricle, followed by pulmonary arterial system.11 Despite its infrequency, it has been described as a life-threatening complication, especially if the stent compromises the cardiopulmonary system causing pulmonary infarction, tricuspid regurgitation, and potentially right-sided heart failure.9,12,13 Risk factors for stent migration include undersized stent, malapposition of stent, inaccurate vessel measurement, and choice of lesion without a significant degree of obstruction.14,15 This complication has been attributed to poor wall contact with the stent device, mainly in a large caliber vein. The size of stent must be at least 1-2 cm greater than the stenotic lesion to avoid stent dislodgement.16 Adequate stent size is indispensable for a successful and safe procedure. In left common iliac vein lesions, it has been recommended to use flexible, self-expanding stents that are 14-16 mm in diameter and at least 60 mm long.10 Furthermore, liberal use of intravascular ultrasound to guide stent sizing should also be practiced.

Several interventional approaches for intracardiac foreign body retrieval have emerged.14,17 The mortality rate of foreign body embolization ranges from 24-60%; therefore, timely intervention is indicated to prevent severe complications such as cardiac arrhythmias, valve injury, and myocardial perforation.18,19 Endovascular and surgical retrieval are the two main interventional approaches.15 Success rates of endovascular intervention exceed 90% compared with surgical technique, which is associated with high mortality.16 Even though endovascular intervention has a high overall success rate, in complex cases in which the stent has migrated across the tricuspid valve or into the pulmonary vasculature, a surgical approach should be preferred.15 A surgical approach offers better visualization and maneuverability to prevent potential cardiac or vascular injury as described in our case.

In summary, our patient underwent an elective left common iliac vein stent placement for management of CVI that could have resulted in a fatal outcome due to stent migration into the right heart. Following appropriate indications and procedural technique is of paramount importance to avoid potentially life-threatening complications. In the future, appropriateness criteria and updated guidelines on endovenous stenting would be beneficial.

References

- Mahnken AH, Thomson K, de Haan M, O'Sullivan GJ. CIRSE standards of practice guidelines on iliocaval stenting. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2014;37:889-97.

- Passman MA. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. Year Bk Vasc Surg 2012;317-8.

- Porter JM, Moneta GL. Reporting standards in venous disease: an update. International Consensus Committee on Chronic Venous Disease. J Vasc Surg 1995;21:635-45.

- Raju S, Neglen P. High prevalence of nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions in chronic venous disease: a permissive role in pathogenicity. J Vasc Surg 2006;44:136-144.

- Neglén P, Thrasher TL, Raju S. Venous outflow obstruction: An underestimated contributor to chronic venous disease. J Vasc Surg 2003;38:879-85.

- Raju S, McAllister S, Neglen P. Recanalization of totally occluded iliac and adjacent venous segments. J Vasc Surg 2002;36:903-11.

- Raju S, Owen S Jr, Neglen P. The clinical impact of iliac venous stents in the management of chronic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg 2002;35:8-15.

- Neglén P, Hollis KC, Olivier J, Raju S. Stenting of the venous outflow in chronic venous disease: long-term stent-related outcome, clinical, and hemodynamic result. J Vasc Surg 2007;46:979-90.

- Bani-Hani S, Showkat A, Wall BM, Das P, Huang L, Al-Absi AI. Endovascular stent migration to the right ventricle causing myocardial injury. Semin Dial 2012;25:562-4.

- Mussa FF, Peden EK, Zhou W, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Bush RL. Iliac vein stenting for chronic venous insufficiency. Tex Heart Inst J 2007;34:60-6.

- Bloomfield DA. The nonsurgical retrieval of intracardiac foreign bodies--an international survey. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1978;4:1-14.

- Antonucci F, Salomonowitz E, Stuckmann G, Stiefel M, Largiadèr J, Zollikofer CL. Placement of venous stents: clinical experience with a self-expanding prosthesis. Radiology 1992;183:493-7.

- Morgan RA, Walser E (eds). Handbook of Angioplasty and Stenting Procedures, Techniques in Interventional Radiology. London: Springer-Verlag London; 2010.

- Taylor JD, Lehmann ED, Belli AM, et al. Strategies for the management of SVC stent migration into the right atrium. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2007;30:1003-9.

- Kang W, Kim IS, Kim JU, et al. Surgical removal of endovascular stent after migration to the right ventricle following right subclavian vein deployment for treatment of central venous stenosis. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2011;19:203-6.

- El Feghaly M, Soula P, Rousseau H, et al. Endovascular retrieval of two migrated venous stents by means of balloon catheters. J Vasc Surg 1998;28:541-6.

- Toyoda N, Torregrossa G, Itagaki S, Pawale A, Reddy R. Intracardiac migration of vena caval stent: decision-making and treatment considerations. J Card Surg 2014;29:320-2.

- Bernhardt LC, Wegner GP, Mendenhall JT. Intravenous catheter embolization to the pulmonary artery. Chest 1970;57:329-32.

- Gabelmann A, Kramer S, Gorich J. Percutaneous retrieval of lost or misplaced intravascular objects. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;176:1509-13.