A 37-year-old pregnant woman who is nine weeks pregnant presented to an outside hospital with progressive dyspnea.

Video 1 and 2

|

|

|

|

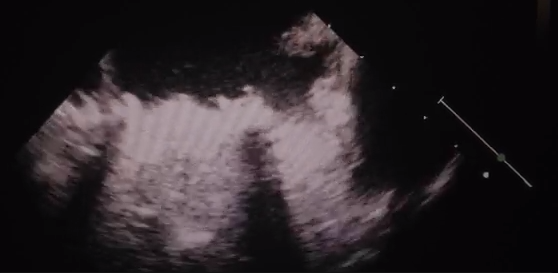

Her past surgical history was notable for three prior valve surgeries in 1999 and 2001, including mitral valve repair, mechanical mitral valve replacement, and tricuspid ring annuloplasty. Given the potential teratogenic effects of warfarin, her initial anticoagulation regimen included enoxaparin. Several days prior to admission, however, she ran out of enoxaparin and restarted warfarin without medical guidance. The patient ultimately presented to an outside hospital with progressive shortness of breath and transthoracic (TTE) echocardiogram demonstrating complete thrombosis of her mechanical mitral valve (Video 1)

On exam, she appeared comfortable with only mild respiratory distress. Her vital signs included: heart rate 114 beats/min.; blood pressure 100/70 mm Hg; fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) 97% on 2 L nasal cannula; and respirations 20/min.

Shortly after admission, the patient developed acute respiratory failure, hypoxia, and pulmonary edema necessitating intubation. PaO2 was 50 mm Hg on 100% FiO2 with chest X-ray demonstrating florid pulmonary edema.

The correct answer is: Answers C and E are both correct.

Critique

Thrombosis of a mechanical prosthetic heart valve (MPHV) is a dreaded complication following prosthetic valve replacement that requires a multidisciplinary approach. Therapeutic options are particularly complicated in pregnant patients, which underscore the importance of wide consultation prior to initiating therapy. Although there is no clear consensus for the management of these patients, the therapeutic options generally include either fibrinolysis or valve replacement/thrombectomy. In this patient, supportive care with systemic heparin anticoagulation and aPTT goal of 50-60 seconds would not be appropriate. Options include either fibrinolysis or surgical valve replacement/thrombectomy. Fibrinolysis alone may not be sufficient for this patient with hypoxia and cardiovascular collapse and the initiation of ECMO for cardiac and respiratory support may be beneficial.

Follow-up

In this patient, a multidisciplinary team including obstetricians, cardiologists, and cardiac surgeons discussed both the medical and surgical therapeutic options with the family, including risks to the patient and the fetus. The decision was made to start systemic fibrinolytic treatment with ECMO support.

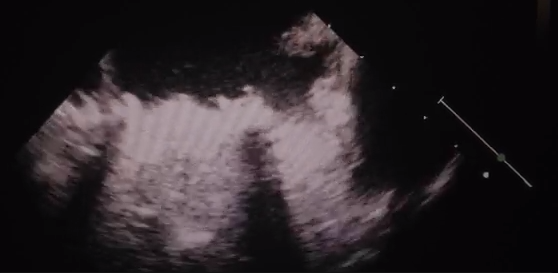

| Video 2 |

|

|

|

The patient was taken emergently to the operating room with percutaneous placement of a 25 Biomedicus cannula into the femoral vein and 17 Biomedicus cannula into the femoral artery. For perfusion of the distal extremity, a retrograde perfusion catheter was inserted into the dorsalis pedis artery. After initiating ECMO support, systemic fibrinolytic therapy with recombinant tissue plasminogen (tPA) was initiated. Repeat TEE on postoperative day one revealed good and symmetric opening of both mechanical mitral leaflets with no signs of inflow obstruction (Video 2). The tPA was stopped; at POD2, she was taken to the operating room for ECMO decannulation.

Discussion

Throughout pregnancy, there is an increase in the prothrombotic changes, which emphasize the importance of choosing an appropriate anticoagulation regimen, especially for women with MPHV.1 The choice of anticoagulant for pregnant patients remains a challenge to the obstetrician. Although oral anticoagulation with warfarin is the most effective treatment in preventing valve thrombosis, warfarin also crosses the placenta and has a high teratogenicity associated with early and late fetal loss. Unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) do not cross the placenta and are safer to the fetus; however, they are less efficient in preventing valve thrombosis.2-4

The reported incidence of thromboembolic complications of women treated with only warfarin, UFH for the first trimester followed by warfarin, and UFH throughout their pregnancy was 3.9%, 9.2%, and 25%, respectively. Maternal death was observed in 2%, 4%, and 15%, respectively, and was usually related to MPHV thrombosis.4 The incidence of MPHV thrombosis in women on LMWH throughout their pregnancy was 15%.5

Therapeutic options for MPHV thrombosis in a pregnant patient include fibrinolysis, valve replacement or surgical thrombectomy. The decision is made based on the patient's clinical status and hemodynamics. In the critically ill patient, surgery is indicated when the prosthetic valve is obstructed or in the presence of a non-obstructive lesion (>10 mm) with evidence of embolism. Fibrinolytic therapy can be considered with right heart mechanical valve thrombosis or when surgery is not immediately available.6, 7 In more recent studies fibrinolytic therapy is emerging as a promising alternative, especially in critically ill patients with a success rate of 75%-88%.8,9 The safety of fibrinolytic therapy in pregnancy is debatable and understudied. High maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity rates are reported in cardiac surgery (6% and 30%) and (24% and 9%, respectively).10 Recent publications demonstrate safety and efficacy of fibrinolysis with very high success rate and low complication rate.11-13

ECMO is a well-established supportive therapy for patients with acute cardiopulmonary dysfunction when other treatments fail.14 Both open and percutaneous cannula placement has been utilized safely.14-16 Experience using ECMO support in pregnancy is very limited, and most published reports are related to 2009 H1N1 influenza.16-19

In this case, the patient had three prior valve surgeries. It was felt that a fourth-time sternal reentry in the setting of acute cardiopulmonary collapse would have yielded unfavorable results. The physicians also felt that fibrinolysis alone would be unsatisfactory. After multidisciplinary consultation with obstetricians, cardiologists, and cardiac surgeons, it was felt that fibrinolysis with ECMO support would be the best therapeutic option.

References

- Schafer AI. The hypercoagulable states. Ann Internal Med 1985;102:814-28.

- McLintock C. Anticoagulant therapy in pregnant women with mechanical prosthetic heart valves: no easy option. Thromb Res 2011;127 Suppl 3:S56-60.

- Castellano JM, Narayan RL, Vaishnava P, Fuster V. Anticoagulation during pregnancy in patients with a prosthetic heart valve. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:415-24.

- Chan WS, Anand S, Ginsberg JS. Anticoagulation of pregnant women with mechanical heart valves: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:191-6.

- McLintock C, McCowan LM, North RA. Maternal complications and pregnancy outcome in women with mechanical prosthetic heart valves treated with enoxaparin. BJOG 2009;116:1585-92.

- Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. 2008 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease). Endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:e1-142.

- Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012): the Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;42:S1-44.

- Silber H, Khan SS, Matloff JM, Chaux A, DeRobertis M, Gray R. The St. Jude valve. thrombolysis as the first line of therapy for cardiac valve thrombosis. Circulation 1993;87:30-7.

- Lengyel M, Fuster V, Keltai M, et al. Guidelines for management of left-sided prosthetic valve thrombosis: a role for thrombolytic therapy. Consensus Conference on Prosthetic Valve Thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30:1521-6.

- Weiss BM, von Segesser LK, Alon E, Seifert B, Turina MI. Outcome of cardiovascular surgery and pregnancy: a systematic review of the period 1984-1996. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;179:1643-53.

- Ozkan M, Gunduz S, Biteker M, et al. Comparison of different TEE-guided thrombolytic regimens for prosthetic valve thrombosis: the TROIA trial. JACC Cardiovas Imag 2013;6:206-16.

- Ozkan M, Cakal B, Karakoyun S, et al. Thrombolytic therapy for the treatment of prosthetic heart valve thrombosis in pregnancy with low-dose, slow infusion of tissue-type plasminogen activator. Circulation 2013;128:532-40.

- Elkayam U and Bitar F. Valvular heart disease and pregnancy: part II: prosthetic valves. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:403-10.

- Roussel A, Al-Attar N, Alkhoder S, et al. Outcomes of percutaneous femoral cannulation for venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2012;1:111-4.

- Chen YS, Ko WJ, Lin FY. Insertion of percutaneous ECMO cannula. Am J Emerg Med 2000;18:184-5.

- Ngatchou W, Ramadan AS, Van Nooten G, Antoine M. Left tilt position for easy extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cannula insertion in late pregnancy patients. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012;15:285-7.

- Robertson LC, Allen SH, Konamme SP, Chestnut J, Wilson P. The successful use of extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation in the management of a pregnant woman with severe H1N1 2009 influenza complicated by pneumonitis and adult respiratory distress syndrome. Int J Obstet Anesth 2010;19:443-7.

- Welch SA, Snowden LN, Buscher H. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza, pregnancy and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Med J Australia 2010;192:668.

- Skrenkova J, Horakova V, Horak P, Koucky M, Dokoupilova M, Kubatova J. [Spontaneous preterm birth in mother in an artificial sleep on ECMO with severe form of H1N1 infection]. Ceska Gynekol 2011;76:204-8.