A 67-year-old female with history of bilateral medial and lateral ankle ulcers presents to the wound center. She noticed the ulcers about 6 months ago and they have enlarged progressively. They currently measure more than 20 cm2 bilaterally. She denies any fever, cellulitis, or other constitutional symptoms. She was treated with systemic broad spectrum antibiotics twice within the last 6 months without any significant improvement in the size of the ulcers. She reports that cultures were not obtained at that time. She reports history of recurrent deep vein thrombosis (DVT), first diagnosed in the left lower extremity in 1992, attributed to ulcerative colitis. She underwent colectomy and ileostomy at that time. She then developed right lower extremity DVT in 1999 related to long-distance travel. On both occasions she was treated with anticoagulation for 6 months. She then developed a third DVT in the left lower extremity, which was considered idiopathic in 2000. She received an interior vena cava (IVC) filter and was placed on long-term anticoagulation with warfarin since then. Hypercoagulable testing at that time was negative. She does not have family history of venous thrombosis.

Wound exam demonstrates large ulcers around the ankle (Figure 1). The wounds are debrided to expose healthy underlying granulation tissue. Venous duplex testing for reflux demonstrates superficial venous reflux in the calf areas of the bilateral great saphenous veins. The sapheno-femoral junctions were competent. Deep venous reflux was noted in the bilateral femoral and popliteal veins. Four layered compression wraps are applied in the wound center every week for 6 weeks without any significant improvement.

Figure 1: Venous ulcerations

The correct answer is: D. Obtain a CT venogram of the IVC and iliac veins.

Chronic venous leg ulcers (VLUs) account to >60% of all leg ulcers. These cause significant morbidity and account to significant health care expenses.1 Compression therapy is the cornerstone for the treatment of VLUs. Compression bandaging promotes the healing of VLUs. Compression socks (30-40 mm Hg), on the other hand, prevent recurrence of ulceration after healing. Compression socks should not be used to treat venous ulcers.2 There is no role for more antibiotic therapy in this setting as there are no clinical signs of local or systemic infection. The great saphenous veins are refluxing only in the calf areas and there is no sapheno-femoral junctional reflux, so this does not warrant saphenous ablation, as per the current guidelines.3

It is important to consider post-thrombotic syndrome and iliocaval obstruction as an underlying cause of venous hypertension leading to venous leg ulcer. Since May and Thurner reported compression of the left iliac vein against the fifth lumbar vertebra by the right iliac artery in 22% of the 432 autopsies, iliac vein compression syndrome, now referred to as May-Thurner Syndrome, is widely believed to increase the risk of ipsilateral iliofemoral DVTs and venous hypertension.4 It is also important to understand that a 50% stenosis of the left iliac vein was also noted in 24% of asymptomatic patients in a study conducted by Kibbe et al.5 So, one should not hunt for this condition in all patients.

Patients with advanced chronic venous insufficiency are known to have complex venous disease involving deep, superficial, and perforator veins.6 Percutaneous stenting to relieve the iliac obstruction also demonstrated improvement in venous hemodynamics, patient symptoms, and quality of life.7,8 In a study of patients with healed and active ulcers, 37% demonstrated iliac vein obstruction of at least 50%, and 23% had obstruction of >80%. Risk factors that were independently associated with a significantly higher incidence of >80% iliac vein obstruction included female gender, medical history of DVT, and reflux in the deep venous system.9 As such, iliocaval obstruction must be considered in this patient since she has all the risk factors. In the present case, a CT venogram was obtained and is the correct choice here. The axial imaging demonstrated chronic iliocaval occlusion from a thrombosed filter on CT venogram (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Chronically occluded infrarenal IVC at the site of the IVC filter. Note the severe retraction seen in the lumen and of the filter itself. Not seen in this image are the robust abdominal wall and peri-lumbar venous collaterals.

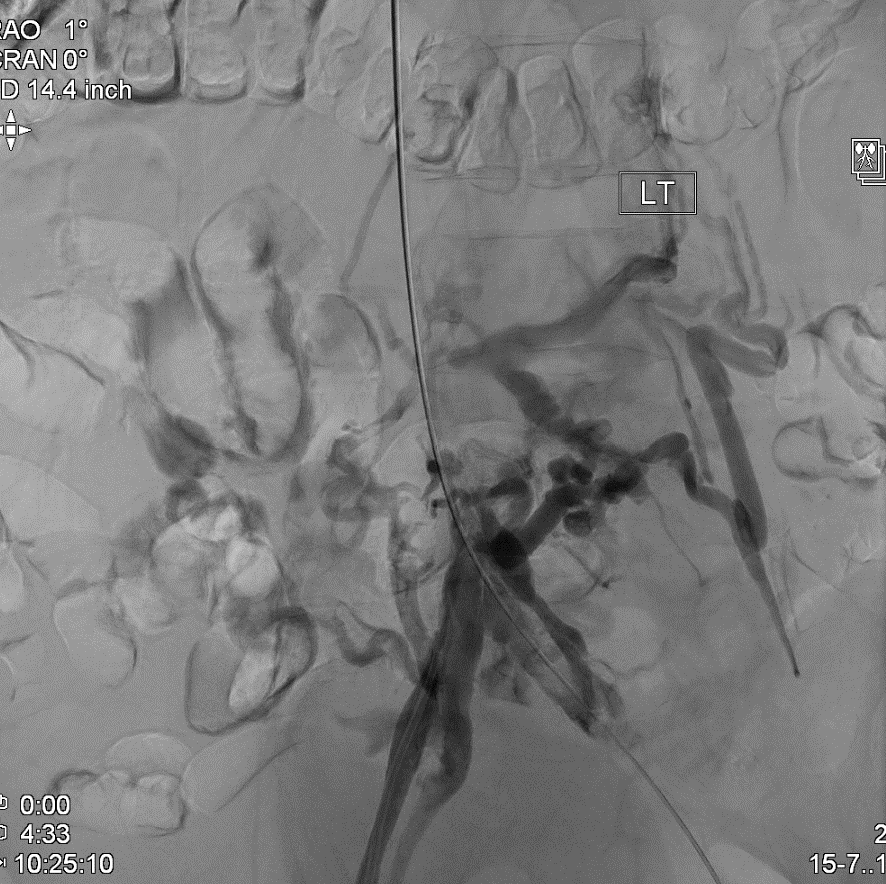

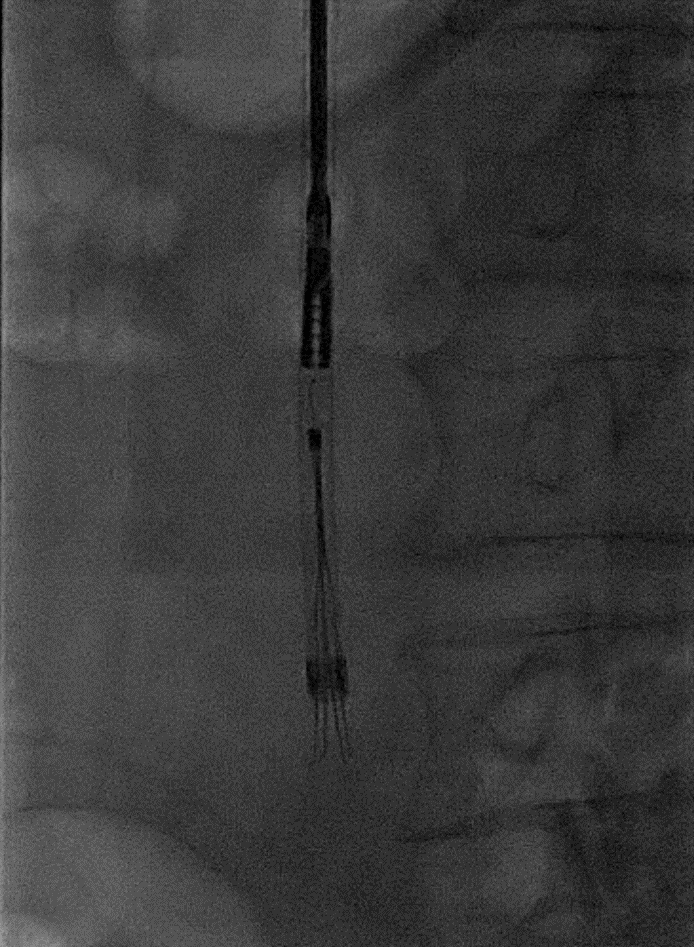

The patient subsequently underwent iliocaval recanalization using standard endovascular techniques. First, contrast venography was performed from the right internal jugular and bilateral common femoral vein access points (Figures 3a and 3b). This demonstrated total occlusion of the infrarenal IVC and iliac veins. Next, the infrarenal IVC filter was successfully snared and retrieved using a laser atherectomy sheath (Figure 4; Spectranetics, Colorado Springs, CO).10 Following successful advancement of guidewires from the common femoral veins into the suprarenal IVC, balloon angioplasty was performed followed by iliocaval reconstruction using a combination of Cook Z stents (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) and Wallstents (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) (Figure 5). This resulted in restoration of anatomic venous flow and functional closure of the collaterals, an important angiographic marker of procedural success.

Figure 3a: Chronic IVC occlusion

Figure 3b: Chronic iliocaval occlusion with extensive collateral development

Figure 4: IVC retrieval using bronchial forceps and laser atherectomy sheath.

Figure 5: Endovascular iliocaval reconstruction with complete restoration of anatomic venous flow.

With continued compression therapy and wound care, the ulcers healed 5 months later.

References

- Abbade LP, Lastoria S. Venous ulcer: epidemiology, physiopathology, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol 2005;44:449-56.

- Partsch H, Flour M, Smith PC, International Compression Club. Indications for compression therapy in venous and lymphatic disease consensus based on experimental data and scientific evidence. Under the auspices of the IUP. Int Angiol 2008;27:193-219.

- Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, Dalsing MC, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 2011;53:2S-48S.

- May R, Thurner J. The cause of the predominantly sinistral occurrence of thrombosis of the pelvic veins. Angiology 1957;8:419-27.

- Kibbe MR, Ujiki M, Goodwin AL, Eskandari M, Yao J, Matsumara J. Iliac vein compression in an asymptomatic patient population. J Vasc Surg 2004;39:937-43.

- Labropoulos N, Patel PJ, Tiongson JE, Pryor L, Leon LR, Tassiopoulos AK. Patterns of venous reflux and obstruction in patients with skin damage due to chronic venous disease. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2007;41:33-40.

- Neglen P, Hollis KC, Olivier J, Raju S. Stenting of the venous outflow in chronic venous disease: long-term stent-related outcome, clinical, and hemodynamic result. J Vasc Surg 2007;46:979-90.

- Nelson EA. Venous leg ulcers. BMJ Clin Evid 2011:1902.

- Marston W, Fish D, Unger J, Keagy B. Incidence of and risk factors for iliocaval venous obstruction in patients with active or healed venous leg ulcers. J Vasc Surg 2011;53:1303-8.

- Kuo WT, Odegaard JI, Louie JD, et al. Photothermal ablation with the excimer laser sheath technique for embedded inferior vena cava filter removal: initial results from a prospective study. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22:813-23.