Putting the 2021 AHA Dietary Guidelines into Practice

Quick Takes

- Physicians lack the adequate training to carry out nutritional counseling.

- A healthy lifestyle including a heart healthy diet is a valuable and cost-effective tool in preventing CVD.

- A strong patient-physician relationship where the clinician spends a portion of the visit emphasizing the importance of healthy dietary habits goes a long way.

Poor diet is a leading cause of cardiovascular disease (CVD), obesity, and type 2 diabetes. CVD is responsible for 1 in every 3 deaths in the United States (US) and approximately 92 million adults are living with CVD.1 About 45% of cardiometabolic deaths are attributable to a poor diet; thus, a healthy lifestyle including a heart healthy diet is a valuable and cost-effective tool in preventing CVD.2

In an era where an overwhelming amount of misinformation regarding nutrition is present on the web and social media, the responsibility of clinicians to educate patients about a healthy diet is more important than ever. Most senior physicians and trainees face the same challenges as many of their patients when it comes to healthy eating. The long hours spent at work coupled with the clinical and academic responsibilities often leaves clinicians with insufficient time to focus on their own health and dietary habits.

Additionally, standard medical training includes very little nutrition education. An online anonymous survey of medical residents, Cardiology fellows and faculty in Internal Medicine and Cardiology at an academic medical center revealed that 13.5% of the participants felt that they were adequately trained in counseling patients about diet, with a majority agreeing that extra training would allow them to deliver better nutritional care.3 A subsequent survey revealed that 67% of Cardiologists spent 3 minutes or less counseling their patients on dietary habits.4

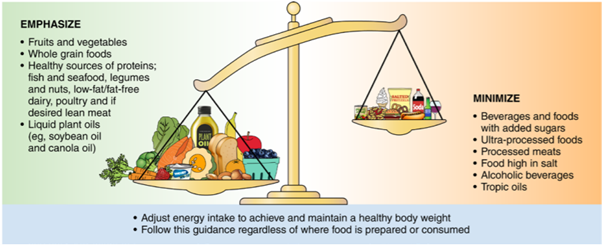

The aim of this commentary is to present a simplified approach to a heart healthy diet that can be easily communicated by healthcare providers to their patients. The focus of our expert analysis is the 2021 American Heart Association (AHA) scientific statement by Lichtenstein et al. which reviewed dietary guidelines to improve cardiovascular health.5 The dietary components to be emphasized and minimized in promoting a heart healthy diet are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Incorporating fruits and vegetables into the diet is beneficial to health. Fruits and vegetables that are deeply colored, such as berries or kale, are dense in their nutritional content.6 Whole fruits and vegetables are also rich in dietary fiber, which results in a more filling meal and longer satiety.

While fresh sources of fruits and vegetables are preferred, frozen, canned, and dried fruits are reasonable alternatives since they contain similar nutritional value. Patients should be counseled about the importance of reading nutrition labels to look for products with high amounts of added salt and sugar, which should be avoided.

Foods that are made with whole grains and the fiber they contain have a beneficial effect on cardiovascular health when compared to refined grains. High-fiber, whole grain diets have been associated with a reduction in the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes, and they promote lower systolic blood pressure and body weight.7 Again, the importance of reading nutrition labels should be emphasized; patients should be encouraged to choose products labeled "100% whole grain," or opt for unprocessed options such as oats, brown rice, or barley.

Protein is a major dietary component and can be obtained from a variety of sources. Given the wide range of options, it is important to choose ones that provide the best nutritional composition. Protein from sources such as legumes and nuts lower cardiovascular disease risk.8 Currently there is no general consensus regarding plant-based meat alternatives due to the evolving nature and lack of short- and long-term studies attesting to their value.

Regular consumption of fish and seafood reduce cardiovascular risk. The benefits of seafood and fish are associated with the presence of omega-3 fatty acids.9 Consuming at least 2 fish meals per week has been associated with reduced rates of stroke, as well as cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.10

When consuming dairy products, it is recommended to choose fat-free or low-fat ones over full-fat products.11 Additionally, when meat or poultry products are desired, choosing lean cuts and avoiding processed meats is beneficial. Consumption of red meat should also be minimized owing to the higher CVD incidence and mortality associated with regular intake.12

Regarding fats, consumption of both mono- and polyunsaturated sources should be emphasized, while saturated and trans fats should be avoided. Sources of unsaturated fat include liquid-based plant oils, such as those derived from sunflower, soybean, and corn, as well as flax seeds and walnuts. These are rich in polyunsaturated fats, which are mainly responsible for their cardioprotective effects.13 Sources of saturated fat, including animal fat, high-fat dairy, and tropical oils, should be minimized.

While it is important to keep in mind what foods that should be emphasized, it is equally important to understand which foods are to be minimized as well. Foods and beverages with added sugar should be avoided altogether or consumed minimally. This recommendation is based on the fact that products with added sugar are associated with an increased risk for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity.14

Foods that have been ultra-processed should be avoided due to their ability to cause a wide range of cardiometabolic disorders.15,16 Many processed foods have a high sodium content, which can worsen blood pressure. Reduction of sodium intake in combination with a DASH diet, i.e., rich in fruits and vegetables, and low in both saturated and total fat, reduces blood pressure more than either approach alone.17

Alcohol has been a controversial topic since low amounts have been seen in observational studies to confer cardiovascular protection. The AHA 2021 dietary guidelines do not recommend initiation or consumption of low amounts of alcohol in an effort to improve cardiovascular outcomes. If one does consume alcohol, it is recommended to have no more than 1 drink per day for women and 2 drinks per day for men.

Many resources are available for both the clinician and the patient. For clinicians, online resources such as the CardioNutrition podcast can be utilized, which provide clinical tips on a core dietary curriculum in small bites. The Cardiosmart website can be used for patients to explore various aspects of heart health or to print hand-outs specific to nutrition.

Clinicians can also use Electronic Medical Records to create smart phrases to be included in the after-visit summary. Referrals to nutritionists and dieticians should happen early and more often. A strong patient-physician relationship where the clinician spends a portion of the visit emphasizing the importance of healthy dietary habits will go a long way.

References

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135:e146-e603.

- Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation 2006;114:82-96.

- Harkin N, Johnston E, Mathews T, et al. Physicians' dietary knowledge, attitudes, and counseling practices: the experience of a single health care center at changing the landscape for dietary education. Am J Lifestyle Med 2018;13:292-300.

- Devries S, Agatston A, Aggarwal M, et al. A deficiency of nutrition education and practice in cardiology. Am J Med 2017;130:1298-1305.

- Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Vadiveloo M, et al. 2021 dietary guidance to improve cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021;144:e472-e487.

- Minich DM. A review of the science of colorful, plant-based food and practical strategies for "eating the rainbow." J Nutr Metab 2019;2019:2125070.

- Ferruzzi MG, Jonnalagadda SS, Liu S, et al. Developing a standard definition of whole-grain foods for dietary recommendations: summary report of a multidisciplinary expert roundtable discussion. Adv Nutr 2014;5:164-76.

- Glenn AJ, Lo K, Jenkins DJA, et al. Relationship between a plant-based dietary portfolio and risk of cardiovascular disease: findings from the women's health initiative prospective cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e021515.

- Krittanawong C, Isath A, Hahn J, et al. Fish consumption and cardiovascular health: a systematic review. Am J Med 2021;134:713-20.

- Rimm EB, Appel LJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Seafood long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;138:e35-e47.

- Jousilahti P, Laatikainen T, Peltonen M, et al. Primary prevention and risk factor reduction in coronary heart disease mortality among working aged men and women in eastern Finland over 40 years: population based observational study. BMJ 2016;352:i721.

- van den Brandt PA. Red meat, processed meat, and other dietary protein sources and risk of overall and cause-specific mortality in The Netherlands Cohort Study. Eur J Epidemiol 2019;34:351-69.

- Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JHY, et al. Dietary fats and cardiovascular disease: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;136:e1-e23.

- Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després JP, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation 2010;121:1356-64.

- Juul F, Vaidean G, Lin Y, Deierlein AL, Parekh N. Ultra-processed foods and incident cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Offspring Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:1520-31.

- Zhang Z, Jackson SL, Martinez E, Gillespie C, Yang Q. Association between ultraprocessed food intake and cardiovascular health in US adults: a cross-sectional analysis of the NHANES 2011-2016. Am J Clin Nutr 2021;113:428-36.

- Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 2001;344:3-10.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Prevention, Lipid Metabolism, Nonstatins, Diet

Keywords: American Heart Association, Cardiovascular Diseases, Diet, Healthy, Helianthus, Nutritionists, Blood Pressure, Cost-Benefit Analysis, Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2, Dietary Approaches To Stop Hypertension, Risk Factors, Nutrition Policy, Fatty Acids, Omega-3, Stroke, Academic Medical Centers, Coronary Disease, Heart Disease Risk Factors, Nutritive Value, Fats, Unsaturated, Sodium, Dietary, Dietary Fiber, Dairy Products, Body Weight, Obesity, Sodium, Sugars, Patient Education as Topic, Healthy Lifestyle, Life Style

< Back to Listings