Dysfunctional Breathing in Athletes: A Brief Primer For the Sports Cardiologist

Quick Takes

- Dysfunctional breathing is an abnormal biomechanical pattern of respiration which can be caused from functional or structural factors resulting in a variety of nonspecific symptoms beyond just breathlessness.

- Identification of this common condition and subsequent management often require a multidisciplinary approach with a high level of suspicion.

- Non-pharmaceutical therapy is the mainstay of treatment by specialists such as speech pathologists.

As the sub-specialty of sports cardiology continues to expand with increasing numbers of practicing clinicians and formal programs/centers, combined with the increasing awareness of sudden cardiac death in athletes, there has been a rapid influx of athlete referrals. While one of the primary roles of a sports cardiologist is evaluating a symptomatic athlete for concerning cardiac pathologies, the sports cardiologist should also be aware of other etiologies of breathlessness and exercise intolerance as well as a wider differential for atypical presentations of chest pain, palpitations, and dizziness. Dysfunctional breathing is relatively common in athletes (particularly younger athletes) with a broad range of presentations. The sports cardiologist should know when to consider dysfunctional breathing in athletes as well as where to refer them for further evaluation and management to avoid potentially unnecessary cardiac workups.

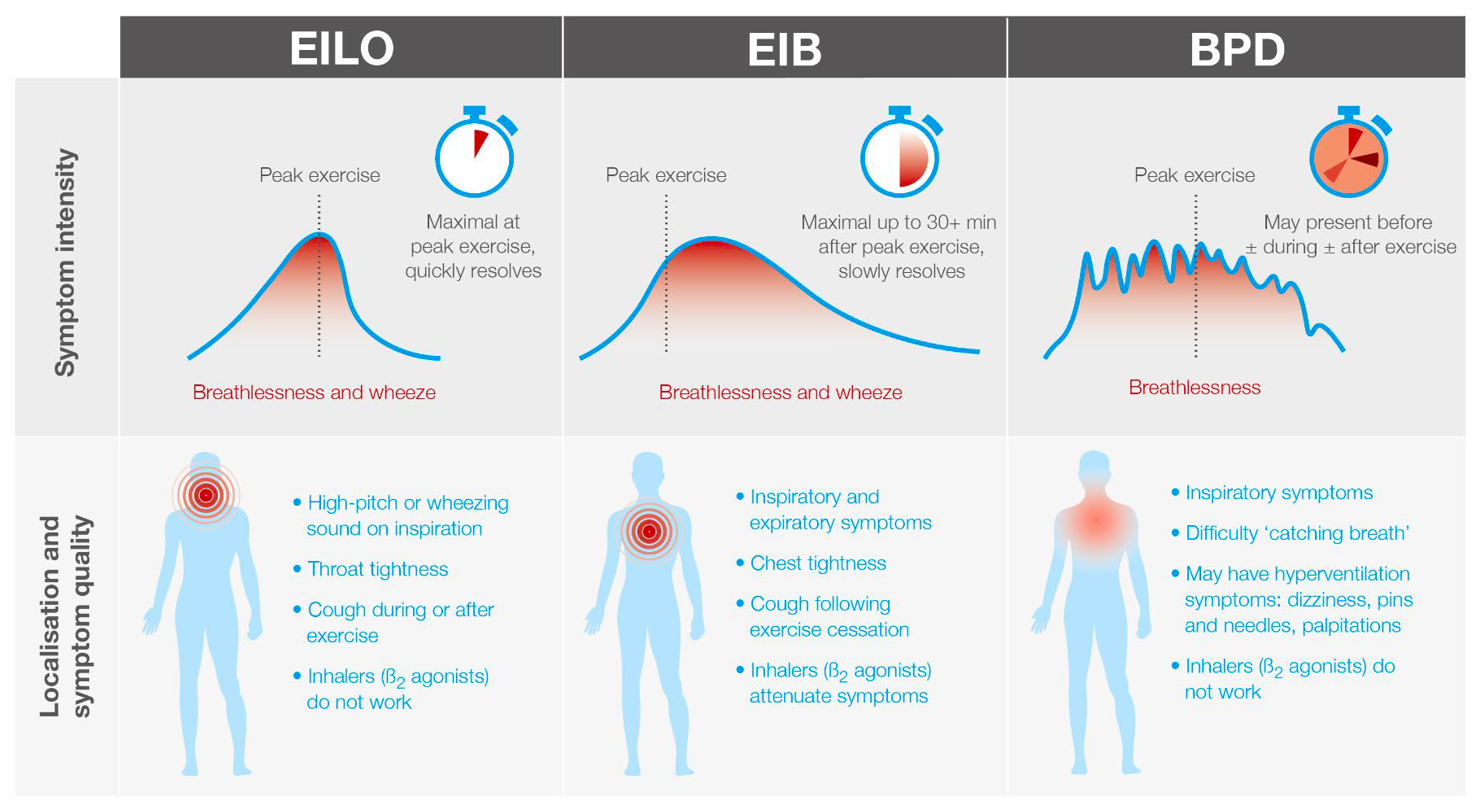

Asthma and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) have a high prevalence in athletes.1 However, the majority of these athletes are primarily referred to pulmonary specialists with the predominant symptoms of pure shortness of breath or wheezing. Dysfunctional breathing is an umbrella term describing an abnormal biomechanical pattern of respiration, which can be caused from functional or structural factors and results in intermittent or chronic symptoms.2 Exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction (EILO), also known as vocal cord dysfunction (VCD), is an extrathoracic cause of dysfunctional breathing that is also relatively common in athletes.3 Breathing pattern disorder (BPD) reflects a poor or inefficient breathing pattern resulting in breathlessness and has become an increasingly recognized etiology for a diverse group of symptoms in young athletes.4,5 With dysfunctional breathing, common concerns include difficulty breathing, difficulty "catching my breath", or an inability to take deep breaths in. These symptoms should be included in a detailed history as a primary inability to inhale may help differentiate these disorders from pulmonary related disease. Figure 1 highlights symptom intensity, quality, and localization between EILO, EIB and BPD.

Figure 1

EILO is the current preferred nomenclature that is inclusive of disorders affecting the glottic and supraglottic structures causing breathing problems precipitated by exercise (Video 1).

Video 1

Beyond dyspnea, additional symptoms can include cough, stridor/wheezing, throat tightness, chest tightness/pain, anxiety and dysphonia.7 EILO affects 5-10% of all adolescents and is particularly more common in females.8 EILO has been reported to be relatively common in athletes, affecting nearly one-third of athletes with respiratory symptoms.3,9 It can mimic and even co-exist with EIB, but it often does not respond to inhaled bronchodilators. Symptoms most often develop during intense exercise and resolve rapidly on exercise cessation with the athlete commonly reporting difficulty breathing in and/or an inability to get a complete breath in. A high level of suspicion from a careful history should prompt referral to a specialist with laryngeal examination during exercise and often be required to confirm a diagnosis.10

BPD can include hyperventilation syndrome, periodic deep sighing, thoracic dominant breathing, hyperfunction of the neck musculature, and thoracoabdominal asynchrony.4 (Video 2)

Video 2

In addition to breathlessness, BPD can result in a host of other symptoms, many of which can overlap with cardiovascular symptoms, such as exercise intolerance, chest pain, dizziness, syncope, and palpitations.5 Currently there is no gold standard diagnostic test or generally accepted classification system, which results in confusion and poor recognition among clinicians. A careful history and physical often provides clues to suspect the diagnosis (Table 1) and basic cardiac testing should eliminate a potential cardiac etiology while avoiding the temptation for exhaustive over-testing.

Table 1

| Bias towards chest breathing (rather than diaphragm breathing) |

| Rapid, shallow breathing pattern during exercise, and possibly at rest (breathing pattern can be regular or irregular) |

| Inability to synchronize breathing to movement cadence with a consistent rhythm |

| Inappropriate ventilatory distress, especially during high intensity exercise |

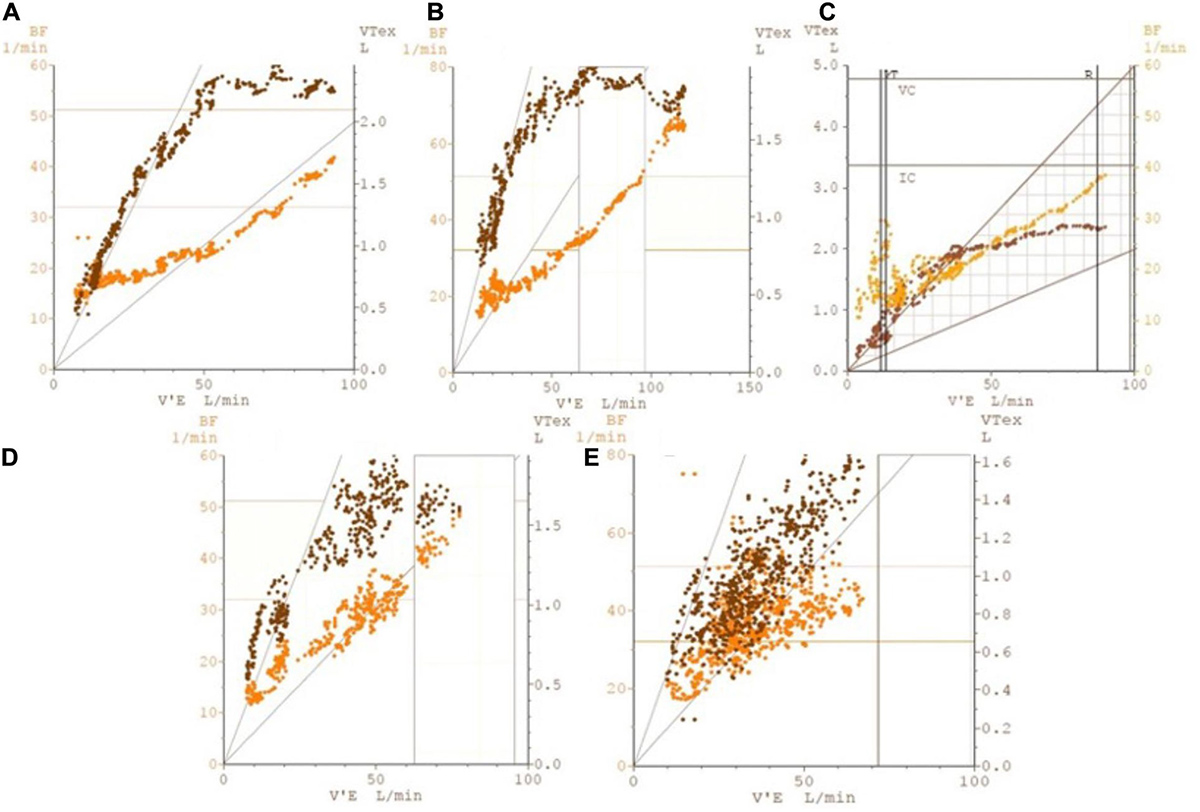

A cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) may be helpful in identifying the irregular and unpredictable nature of BPD (Figure 2) which can also help distinguish it from the more characteristic rhythmic nature of periodic breathing associated with heart failure.12

Figure 2

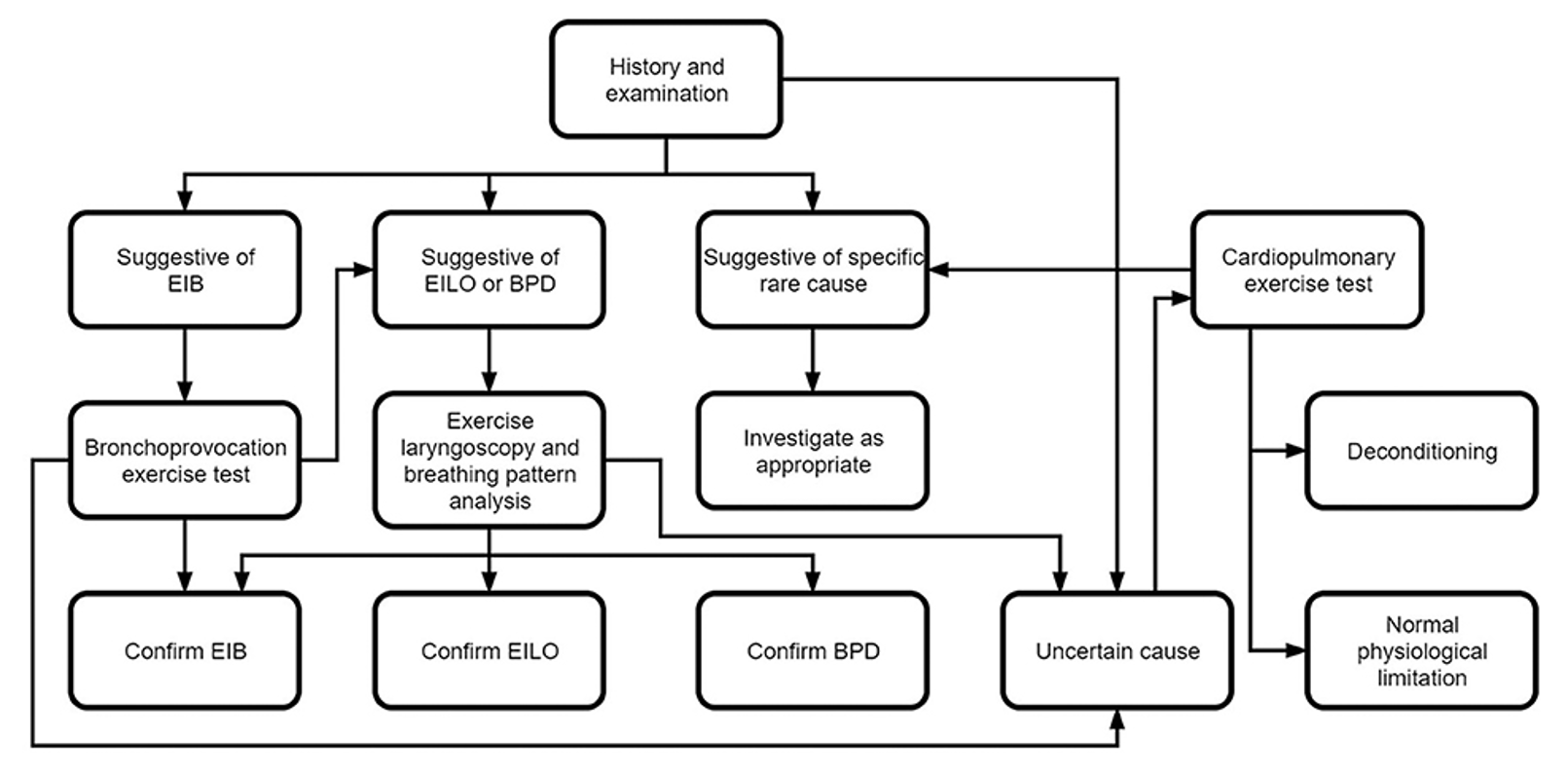

Both EILO and BPD are treatable, but identification and management often require a multidisciplinary approach with a high-level of suspicion. Barker et al.13 have proposed an algorithm (Figure 3) to assist clinicians through diagnostic testing in which the sports cardiologist may play a potential role. As non-pharmaceutical therapy is the mainstay of treatment, subsequent referral to a specialized speech pathologist with expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of these disorders is pivotal in improving the athlete's overall clinical status. Treatment should include having the athlete not only improve their breathing control and pattern(s) at rest, but also transition therapies into higher levels of exertion consistent with their athletic performance.

Figure 3

Breathing disorders including EIB, EILO and BPD are relatively common in athletes and can present with a variety of nonspecific symptoms beyond just breathlessness. The sports cardiologist should be familiar with these disorders as many symptoms may overlap with common cardiovascular complaints. High clinical suspicion should prompt referral to specialists capable of not only affirming the diagnosis, but also providing appropriate therapies to improve the athlete's physical well-being and performance.

References

- Boulet L-P, O'Byrne PM. Asthma and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in athletes. N Engl J Med 2015;372:641-648.

- Depiazzi J, Everard ML. Dysfunctional breathing and reaching one's physiological limit as causes of exercise-induced dyspnoea. Breathe (Sheff) 2016;12:120-29.

- Nielsen EW, Hull JH, Backer V. High prevalence of exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2013;45:2030-35.

- Boulding R, Stacey R, Niven R, Fowler SJ. Dysfunctional breathing: a review of the literature and proposal for classification. Eur Respir Rev 2016;25:287-94.

- CliftonSmith T, Rowley J. Breathing pattern disorders and physiotherapy: inspiration for our profession. Phys Ther Rev 2011;16:75-86.

- Hull JH, Burns P, Carre J, et al. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement for the assessment and management of respiratory problems in athletic individuals (thorax.bmj.com). 2022. Available at: https://thorax.bmj.com/content/early/2022/04/06/thoraxjnl-2021-217904. Accessed 04/12/2022.

- Shay EO, Sayad E, Milstein CF. Exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction (EILO) in children and young adults: from referral to diagnosis. Laryngoscope 2020;130:E400-06.

- Johansson H, Norlander K, Berglund L, et al. Prevalence of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction and exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction in a general adolescent population. Thorax 2015;70:57-63.

- Irewall T, Backlund C, Nordang L, Ryding M, Stenfors N. High prevalence of exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction in a cohort of elite cross-country skiers. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2021;53:1134-41.

- Hull JH, Backer V, Gibson PG, Fowler SJ. Laryngeal dysfunction: assessment and management for the clinician. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194:1062-72.

- Dickinson J, McConnell A, Ross E, Brown P, Hull. J. The BASES expert statement on assessment and management of non-asthma related breathing problems in athletes. Sport Exerc Sci 2015;45.

- Ionescu MF, Mani-Babu S, Degani-Costa LH, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the assessment of dysfunctional breathing. Front Physiol 2021;11:620955.

- Barker N, Thevasagayam R, Ugonna K, Kirkby J. Pediatric dysfunctional breathing: proposed components, mechanisms, diagnosis, and management. Front Pediatr 2020;8:379.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Acute Heart Failure, Sports and Exercise and ECG and Stress Testing

Keywords: Respiratory Sounds, Bronchodilator Agents, Bronchoconstriction, Exercise Test, Prevalence, Cough, Diagnostic Tests, Routine, Dizziness, Dysphonia, Hyperventilation, Pharynx, Physical Exertion, Athletes, Vocal Cord Dysfunction, Dyspnea, Athletic Performance, Death, Sudden, Cardiac, Heart Failure, Algorithms, Chest Pain, Referral and Consultation, Syncope, Anxiety

< Back to Listings