Cover Story | Hospital-at-Home: The New Frontier

Imagine your heart failure (HF) patient weathering their next decompensation from the comfort of their own bedroom, surrounded by family, eating home-cooked food (hopefully healthy), and sleeping (uninterrupted) in their own bed, while also receiving IV diuresis and stepped treatment, daily visits from an advanced care clinician, plus all appropriate monitoring.

The concept of home-based, hospital-level health care is here, pushing the boundaries of medical possibilities, relieving overburdened hospitals, and making patients more satisfied than once thought feasible.

Home-based health care is a transformative approach that challenges the traditional notion of medical care. It envisions a scenario where advanced medical treatments and services are brought to the comfort and familiarity of a patient's own residence.

The concept offers numerous benefits – enhanced patient comfort, reduced risk of hospital-acquired infections and the preservation of patients' sense of independence, among others – but also comes with a multitude of challenges around regulations, reimbursement, staffing, documentation, patient safety and more.

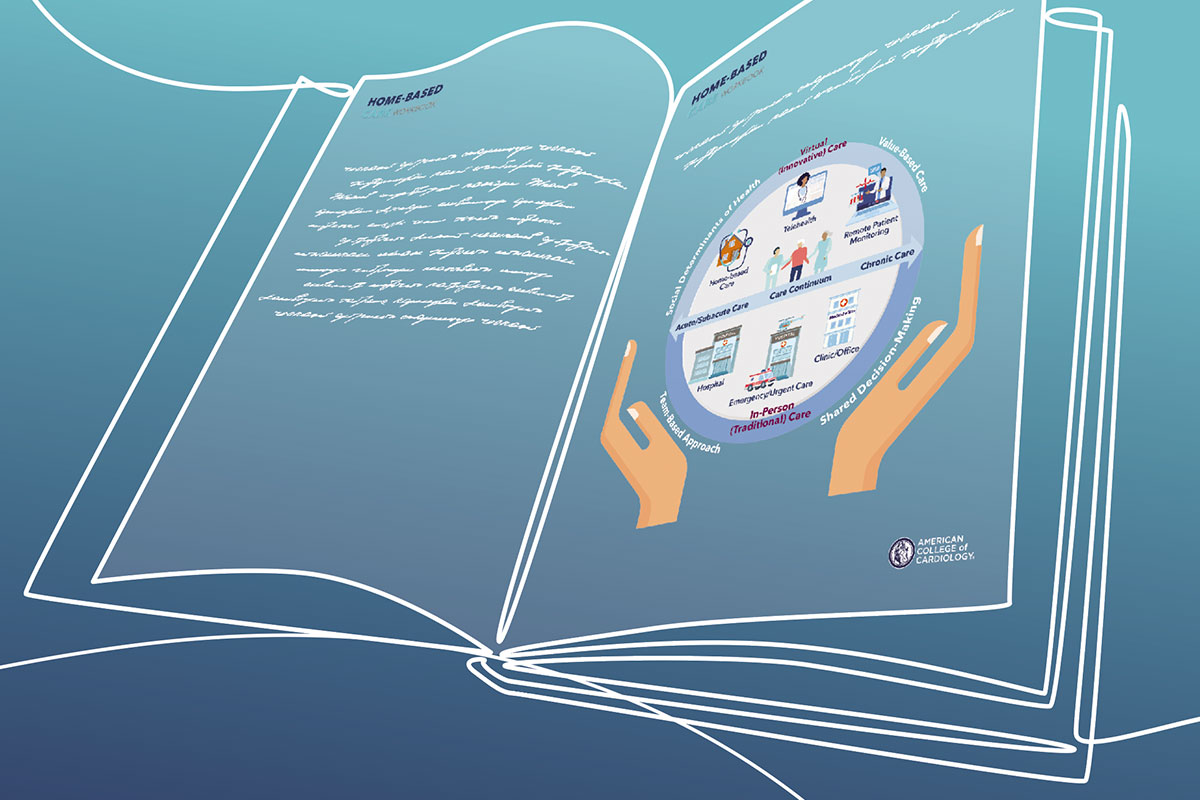

In the pure "hospital-at-home" model, patients with various medical conditions can receive tailored treatment at home, avoiding a hospital admission altogether or reducing length of stay. But home-based care also can be as simple as sending a patient with HF home with a blood pressure (BP) cuff and a scale to monitor congestion remotely.

Home-based care, along with virtual care, received an important boost during the COVID-19 pandemic and a growing number of clinicians and administrators are keen to see those processes finessed, expanded and made permanent. As such, the industry is growing across all segments – medical, skilled, supportive, hospice, etc.

ACC Workbook Provides Guidance

Recognizing ongoing interest within the cardiology community, the ACC published the Home-Based Care Workbook in September, available online.

The Workbook covers prime drivers of home-based care, its advantages and disadvantages, guiding principles and objectives for developing a home-based care program, and key performance indicators to measure its success, among other topics. It finishes off with several cardiac-specific clinical scenarios where it may be used, highlighting ways in which clinicians can keep their patients home more (see sidebar).

"In the workbook, we discuss some of the ongoing challenges related to home-based care programs, which include questions about how to staff these models, and patient-related challenges, like who is going to be in the home with the patient providing care," says Nivee Amin, MD, MHS, FACC, chair of the workbook writing committee. "We also talk about payer issues and the potential added clinical value to situations like same-day discharge (SDD) after cardiac procedures and home-based monitoring for heart failure."

– Nivee Amin, MD, MHS, FACC

The Workbook is designed to be the beginning of the journey. "It's not a comprehensive playbook that provides every answer for how to implement home-based care; rather, it provides a framework for those interested in moving cardiac care to the home and the various stakeholders they might want to engage in the process," says Ty J. Gluckman, MD, MHA, FACC, co-chair of the writing committee with Sanjay Gandhi, MBBS, MBA, FACC.

Gluckman is medical director of the Center for Cardiovascular Analytics, Research, and Data Science at the Providence Heart Institute in Portland, OR, and Gandhi has an appointment at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, OH, and recently took a position as senior director of Medical Strategy and Innovation at Philips. Amin has an appointment in cardiology at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York and is cardiovascular digital health lead at Bristol Myers Squibb.

Mostly, the ACC Workbook authors hope to guide the cardiology community in staying one step ahead of some anticipated health care realities.

Creating a Win-Win

With ravages of the pandemic still apparent in hospitals in the form of persistent staffing shortages and bed capacity issues, this approach offers a promising means to reduce the burdens faced by overcrowded health care facilities.

"During the pandemic when we couldn't care for our patients in the hospital, we were able to demonstrate that we could take care of them using remote options like telemedicine, remote monitoring and home visits," says Amin.

"Now, with dozens of hospitals closing, or at risk of closing, and major resource limitations in health care, we have to think about ways to keep patients out of the hospital and lengthen the interval that patients are seen in the clinic, making sure we're still touching our patients as frequently as we would like to," she adds.

However, implementation of home-based care isn't without challenges. Ensuring the availability of specialized equipment, maintaining stringent medical protocols, and addressing emergency situations in a home environment require careful planning and coordination.

In an interview with Cardiology, Gandhi expressed concern over costs being shifted to patients. "In the hospital, there are nurses taking care of the patients, but when they go home the round-the-clock care is often shifted to family members, who are not reimbursed. There's been some talk about how to compensate these caregivers, but I don't think it's been talked about enough, and I haven't seen any proposed solutions," he says.

On the flip side, family members save time and cost of traveling to the hospital every day and benefit in other ways from being able to care for their loved one at home, he notes.

Another potential extra cost to patients is outpatient pharmacy. Medicare and other payers typically pay for inpatient pharmacy charges, but if the prescriptions given are considered part of outpatient care, the patient may incur additional costs.

"If we can work out all these details – and, most importantly, if we can show equal or improved patient outcomes – there is an opportunity with home-based care to offer a solution that really provides patient-centered care and vastly improves the patient experience and very likely lowers costs for payers, creating a unique win-win," says Gandhi.

Home is More Hospitable

"What we've seen in the last few years, certainly with COVID-19, is that patients want to be discharged from the hospital as quickly as possible and not go to a post-acute rehab or skilled nursing facility if they can be safely discharged home," says Paul N. Casale, MD, MPH, MACC, a cardiologist and the executive director of NewYork Quality Care, the accountable care organization of NewYork-Presbyterian, Columbia, and Weill Cornell Medicine.

– Sanjay Gandhi, MBBS, MBA, FACC

"To facilitate an earlier discharge to home, we've been adjusting our process with our home health partners to provide more high-acuity services and more frequent monitoring, so we can get them home safely."

Medical care at home is an old concept and still a popular one in other countries. For centuries, house calls were a regular component of clinical care, and in many other countries, including England, the Netherlands, and Israel, providing care at home, particularly for the elderly, is an important component of their universal care systems.

In fact, the relative lack of home care services in the U.S. may be a reflection of a changing health policy. Prior to 1997, home care was the fastest-growing segment of the health care industry, with home health agencies reimbursed primarily on a fee-for-service basis. From 1990 to 1996, Medicare spending for home health grew an average of 29% a year, from $3.9 billion to $18.3 billion. These benefits were capped with the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, which served to quickly reduce expenditures.

"Just like in other areas of health care, there are some doing a great job with this and others who have spotted this as a good opportunity. What we need to see are outcomes," says Gluckman. "Does home care lead to improved patient satisfaction? Does it improve the quality of care delivered? And is it more expensive, less expensive, or neutral overall? From the data we've seen so far, it looks good, but we're still in the early stages of this."

So far, the data, albeit limited, look promising. In a 2016 Cochrane review of 16 randomized controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of hospital-at-home care for patients with conditions including COPD, stroke and a mix of other acute conditions, no difference was seen in six-month mortality or in the likelihood to be transferred or readmitted to a hospital. Satisfaction with the care received was higher and costs appeared to be reduced.1

In a small (n=91) randomized clinical trial from 2019, the adjusted mean cost of an acute care episode was 38% lower for home care patients than for usual care patients. The patients treated at home had fewer laboratory tests, imaging studies and consultations, spent less time sedentary or lying down, and were readmitted less frequently within 30 days (7% vs. 23%).2

"Looking at hospital bed capacity and an aging population, I think we need to embrace home-based care as a possible solution, as these problems are unlikely to disappear on their own," Gluckman adds.

While payer support for these care approaches remains a significant barrier to more widespread adoption, accountable care organizations and value-based payment models may ultimately serve to help accelerate home-based care.

"What we need is for payers to create a payment around the significant number of patients who, let's say, get admitted to the hospital for their cardiac issues, but could go home sooner if they had better support. So, a comprehensive or a global payment for the entire early post-discharge time-period is needed, rather than paying for care for each individual service provided, where you're reimbursed for this but not for that," says Casale.

"This certainly could fit within a bundled, value-based payment model, where you can care for the patient safely, maintain quality, and be able to reduce costs," he adds.

CMS Waiver Extended Through 2024

In response to resource challenges faced by hospitals during the height of the COVID-19 public health emergency, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented the Acute Hospital Care at Home (AHCaH) initiative, a flexibility to allow hospitals to expand their capacity to provide inpatient care in an individual's home. The waiver means that Medicare and Medicaid will pay for hospital-level care delivered at home at the same rate as inpatient care.

As a safeguard against overutilization, patient entry to AHCaH was limited to patients seen in Emergency Departments (EDs) or those already admitted to inpatient wards.

To get a waiver approved, hospitals are required to provide a wide range of inpatient services in the home, including pharmacy services, infusions, respiratory care including oxygen delivery, diagnostic labs and radiology, patient transportation, food services, durable medical equipment, social work and care coordination, as well as physical, occupational and speech therapy.

Monitoring requirements are rigorous, and CMS is tracking unexpected mortality. Up to Oct. 27, 2021, 1,878 patients (from 186 hospitals and 82 health systems across 33 states) were "admitted" using the waiver. From these, eight unexpected deaths were reported, for an overall rate of 0.43, which is lower than reported rates for patients treated in-hospital or for those hospitalized for pneumonia.3 It should be noted that in many cases, "avoided" hospitalizations by these patients were at hospitals at or over 100% capacity at the time.

– Ty J. Gluckman, MD, MHA, FACC

Under the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, the AHCaH initiative has been extended through Dec. 31, 2024. This is well beyond the end of the public health emergency, which to many is a good indication that CMS plans to continue to provide funding for hospital-at-home services long term. Hospitals can continue to apply to participate in the initiative.

CMS is carefully monitoring and collecting data from the more than 400 hospitals participating in the waiver program to determine whether it's working and where it might need tweaking. In general, whatever CMS decides to do is copied by private health insurance companies. Most private payers do not currently cover hospital-level care in the home setting.

To provide immediate relief to some specific areas and to recognize their "extensive experience" in acute hospital care at home, six health systems were approved for the waivers in November 2020 on the day the initiative was announced. Two of these hospitals include Brigham and Women's Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital.

The integrated health system, Mass General Brigham (MGB), started investing in hospital-at-home before it became more popular. Since 2016, MGB has delivered hospital-level care to thousands of acutely ill patients in the comfort of their own homes, making them one of the leaders of the hospital-at-home movement in the U.S.4

Now they're going all in on it and hoping the CMS waiver is renewed but planning to stick it out even if it's not. In an Aug. 7, 2023, Modern Healthcare article, the Boston provider, which is the largest employer in Massachusetts, says it's on track to shift 10% of inpatient care to hospital-at-home within five years.5

Read and Learn

Visit ACC.org/HomeBasedCare to learn more and download the Workbook.

MGB is currently offering hospital-at-home services for what amounts to 30 beds per day and plans to increase that to 200 beds per day within a few years.

"With hospitals closing or at risk of closing, along with ongoing staffing issues in almost all our hospitals, I think it's very reasonable to ask where and how all these patients are going to be treated," suggests Amin.

In terms of physician acceptance, Gandhi notes that most clinicians appear open to their patients spending less time inside the confines of the hospital, "but they don't want to deal with the logistics, on top of all the administrative tasks they already have."

Hospitals systems (and clinicians) needn't go it alone. There are outside vendors waiting to help with staffing and logistics. DispatchHealth is one such company. They provide in-home high-acuity medical services using teams trained in emergency medicine and internal medicine that are equipped with all the tools necessary to treat common to complex injuries and illnesses outside of the hospital and reduce unnecessary emergency room visits, hospital stays and readmissions. Several other companies across the country have also entered this space, including Healing Hands, Contessa Health, and Medically Home.

Gluckman sums it up: "It's honestly hard to imagine a world today where this doesn't make sense, whether contracting with a third party or doing it wholesale on your own as a health system."

"Of course, the devil's always in the details, but I think from a patient-centered approach, this makes sense. From a clinician perspective, this makes sense. From a hospital capacity standpoint, this makes sense. And from a payer perspective (especially if you're involved in a value-based payment arrangement with downside risk), this makes sense. Then, it's just a matter of figuring out how to do this as efficiently and effectively as possible."

Clinical Use Cases Ready to Roll Out

It's been argued that the traditional approach in caring for patients with HF – inpatient care for scheduled interventions and acute management of decompensation and outpatient care early after discharge with follow up thereafter – isn't particularly effective in preventing disease progression.1

"It's important to recognize that there is a continuum that goes from providing more home-based care, which in the case of heart failure might be a BP cuff and a scale, to a true hospital-at-home model where the home becomes the service site at which hospital services are provided," notes Craig J. Beavers, PharmD, FACC, another of the workbook's authors. Beavers is the vice president of Professional Services at Baptist Health Paducah in Kentucky.

Using HF as a clinical use case, this continuum is easy to recognize. Are we facilitating a better transition of care and safer discharge to home? Maybe early discharge to home? Or can we provide equivalent or better care to a patient with acute decompensation at home and, better yet, provide chronic HF management that lets us avoid hospitalization and readmission altogether?

Ideally, suggests Beavers, the goal would be to prevent HF hospitalizations by using remote monitoring and home-based care to catch patients earlier in the decompensation process.

"Once we see the patients in the hospital, they're usually already behind the eight ball, so to speak. But had we been able to address that patient's issues earlier in their decompensation, we might have either prevented the admission or readmission, or the degree of decompensation would have been less."

How many avoided HF admissions are we talking about? "I'd hazard to say most can be avoided, if we really embrace this idea of better managing patients with chronic HF remotely," says Beavers.

He estimates that maybe only 20% of HF admissions are strictly necessary given the resources now available for acute, post-acute, and chronic HF home-based care.

New evidence seems to support this assertion. In a recent publication, Scholte, et al., presented results of a comprehensive meta-analysis of studies on home telemonitoring systems (hTMS) in HF, incorporating all variants on the concept over the last 25 years of development.2

They included 65 noninvasive hTMS studies and 27 invasive hemodynamic hTMS studies, including a total of 36,549 HF patients, with a mean follow-up of 11.5 months. Noninvasive monitoring included telemonitoring, structured telephone support and complex telemonitoring, while invasive monitoring includes cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) and invasive hemodynamic monitoring.

Compared to standard of care, hTMS was associated with a 16% reduction in all-cause mortality (pooled odds ratio [OR], 0.84; 95% CI, 0.77-0.93), a 19% reduction in first HF hospitalization (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.74-0.88), and a 15% reduction in total HF hospitalizations (pooled incidence rate ratio, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.76-0.96).

On the electrophysiology (EP) and implantable device side of things, there is increased interest in SDD for patients undergoing CIED placement and catheter ablation of their arrhythmias. Traditionally, both groups have been monitored overnight in the hospital after the procedure.

"Electrophysiology, perhaps more than other subspecialties, has had to integrate nontraditional care models earlier because we care for patients with pacemakers and CIEDs requiring remote monitoring. To monitor thousands of patients in one clinic, we've needed to develop systems to keep tabs on folks from a distance and integrate those into our care process," says Workbook author and electrophysiologist at the University of Colorado (Aurora, CA), Lukasz P. Cerbin, MD.

For Cerbin, SDD after an EP procedure is prime ground for an early foray into home-based care, and one that is low risk and likely to make patients happy. A home-based visit after catheter ablation might entail medication reconciliation, assessment of the access site, lab work (if necessary), and maybe a virtual visit with the procedural/EP team.

In a large (n=6,600) cohort of patients post ablation for atrial fibrillation, those discharged to home the same day had a similar 30-day composite rate of post-ablation complications and one-year composite rate of atrial fibrillation recurrence, compared with those kept for an overnight stay. Studies have shown SDD after cardiac device implantations to be safe, with no increase in procedure-related complications.3

"I think we're increasingly seeing that the standard overnight stay after a CIED placement or EP procedure isn't routinely necessary," says Cerbin. "Patients are happy to be able to go home after and either they come back the next day to check in or we can send someone to the patient's home. In the case of a CIED, for example, that might be to check the wound and pocket and do a PA and lateral chest X-ray using a portable device to make sure the leads are in place and there's no pneumothorax."

While home-based device interrogation would ideally be performed by a technician who is able to obtain lead thresholds, clinics may opt for remote transmissions early after implant, with in-person interrogation one month post procedure, according to the Workbook.

"If there's a dislodgement when we ask the patient to push over a remote transmission, we're likely to see some parameters changing, so we'll know to bring the patient in. But this is not a common issue at all. And, with the increasing numbers of patients we're seeing in our EP and device clinics, this could really help us manage our resources better," he says.

Cerbin adds, "EP is prime to capitalize on the possibilities that home-based care offers to improve patient satisfaction and lower resource utilization without compromising patient safety. I hope that my colleagues seize the opportunity!"

References

- Koehler F, Hindricks G. Is telemonitoring for heart failure ready after a journey longer than two decades? Eur Heart J 2023;44(31):2927-9.

- Scholte NTB, Gürgöze MT, Aydin D, et al. Telemonitoring for heart failure: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2023;44:2911-26.

- Trongtorsak A, Kewcharoen J, Thangjui S, et al. Same-day discharge after implantation of cardiac implantable electronic devices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol PACE 2021;44:1925-33.

This article was authored by Debra L. Beck, MSc.

References

- Shepperd S, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(9).

- Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2020;172:77-85.

- Clarke DV, Newsam J, Olson DP, et al. Acute hospital care at home: The CMS waiver experience. Catal Non-Issue Content 2021;2(6).

- Conley J, Snyder GD, Whitehead D, Levine DM. Technology-enabled hospital at home: Innovation for acute care at home. NEJM Catal 2022;3(3):CAT.21.0402.

- Mass General Brigham bets big on hospital-at-home. Modern Healthcare. Published August 4, 2023. Accessed August 21, 2023. Available here.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, COVID-19 Hub

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Pandemics, COVID-19, Medicare, Workforce, Telemedicine, Innovation

< Back to Listings