What Patient Centric Care Really Means

Drive nearly any major highway in America and you are bound to see multiple health care-related billboards. Many of these billboards will have a theme told through the lens of a patient and tout the organization’s personalized, patient centric approach. A health care provider who delivers care in a tailored and personal manner is seen as such a strategic differentiator that it becomes worthy of a billboard. In a way, these ads are an unfortunate indictment on the way care is more commonly provided across our country, which tends to be fractured and disconnected, with efficiency focused on the providers and not on the patient.

Finding a few positive case examples from the thousands of patients treated in a typical health care system and showcasing the outcomes through paid advertising is straightforward and easy. The extremely difficult part is consistently delivering true patient centric care. What does this mean and what is patient centric care?

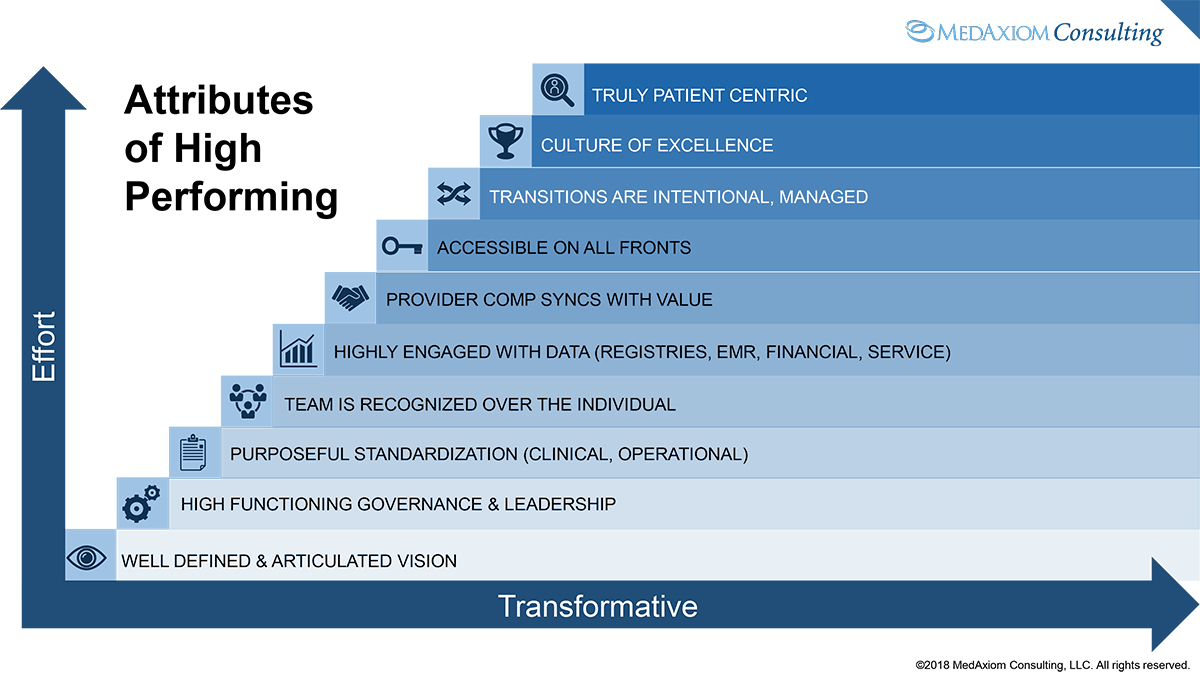

Answering these questions is critically important because not only it is the right thing to do but also more and more of our reimbursement is tied to our ability to deliver patient centric care. The paragraphs below will attempt to answer this question detailing the attributes that transform an organization to patient centeredness. These characteristics will be presented in a hierarchical order where both effort and impact increase as we move through the list (see Figure 1).

Well-Defined and Articulated Vision

An organization’s vision is a simple and straightforward expression of its current roadmap. It is something every employee in the organization should understand and be able to relay to a complete stranger in an elevator with only a few floors of travel time. When Nike first came into existence, Adidas was the worldwide leader in athletic shoes. In these early years, Nike’s vision was very simple: beat Adidas. Everyone from the receptionist to the CEO knew it and could tell you within a single floor journey.

Creating a cardiovascular vision that can be expressed as simply and eloquently as this may be a considerable challenge. However, having no vision at all — as the saying goes — will lead to everywhere and anywhere, which is nowhere. Organizations that take the time to develop a clear understanding of what they want to achieve and then disseminating that vision to every level within the enterprise will have a much higher likelihood of achieving their goals. This vision may be set at the company level (health system or physician group) or within a specific clinical domain such as the cardiovascular service line.

Once established, the vision should drive all organizational decisions, strategies and tactics going forward and everything should be considered through its lens. It is then the job of leadership to execute.

High Functioning Governance and Leadership

At a recent health system Board of Directors meeting, the chairman — who also happened to be a cardiologist — noted, “Without effective governance and leadership, nothing else matters.” His salient point was that without the infrastructure to take our vision through implementation and ongoing monitoring, it would provide dubious value and impact to our patients and organization. In short, it would likely flounder.

In order to be effective, physicians must have meaningful roles throughout the leadership system, from the executive levels down through each front-line committee. As captains of the clinical ships, physicians control or influence nearly 100 percent of health care’s outcomes and costs. To ignore this fact and limit physician participation to the periphery or superficial oversight roles could be considered absurd.

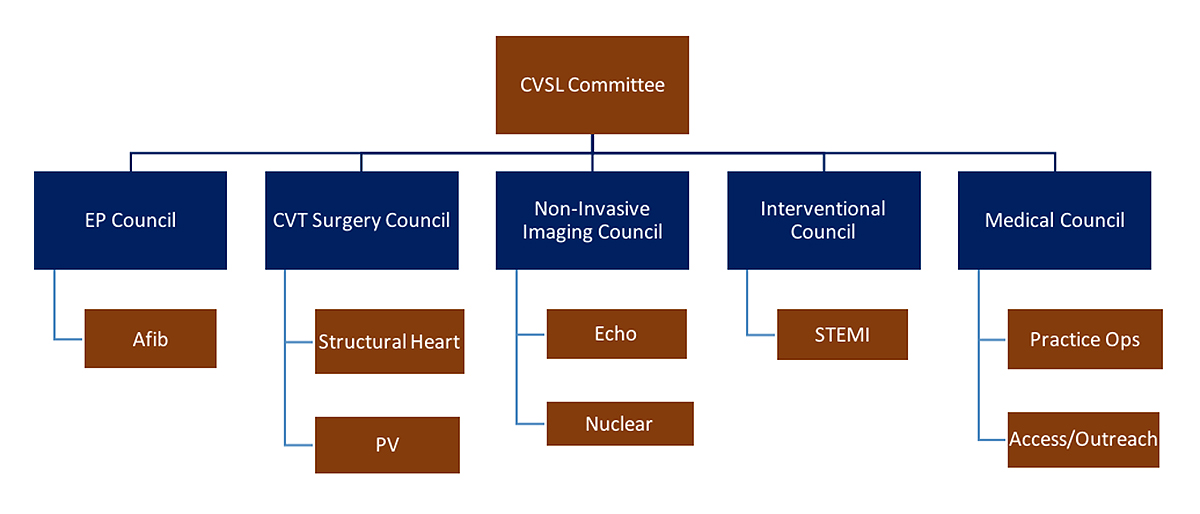

Effective governance and leadership also considers the entire care spectrum, breaking down artificial barriers such as tax identification numbers. For instance, the majority of integrated cardiologists are employed in a separate legal entity (tax ID) from the hospital within a health system. These unique tax entities often also have separate governance structures to manage them. While perhaps some elements of this separation are necessary, if the leadership chasm gets too wide or isolated – which happens all too often in today’s world – misguided decisions that hurt both our organization and patients can occur.

For example, a well-intentioned cost savings initiative in the physician practice may hurt our ability to work with urgent patients. This results in our patients utilizing the emergency department instead, which leads to an increase in avoidable readmissions. When our leadership structures do not consider the entire care spectrum, we hurt our patient centricity. Figure 2 shows a cardiovascular governance and leadership model that spans the care spectrum.

Leadership is hard work and requires a much different set of skills than being a clinician. Thus, organizations who are truly on a path to patient centricity commit the resources necessary to train and develop their teams, physicians and administrative dyads alike. It is a telling sign of an organization’s culture and commitment when the first expense item cut in a financial downturn is education and training. Is this consistent with delivering patient centric care?

Regardless of the competency and organization of the leadership team, it is impossible to manage chaos. Thus, there must be a systematic approach to the delivery of care.

Purposeful Standardization

Over the past five-plus years, there has been a tremendous amount of consolidation in the health care industry. Hospitals and health systems have merged or been acquired, both at a regional and national level. Additionally, private physician practices have been acquired by these hospitals and health systems to the point where now more than 40 percent of practicing physicians in the U.S. are in an employment model. That rate is significantly higher in cardiovascular medicine, surpassing 70 percent in the 2018 MedAxiom Cardiovascular Provider Compensation and Production Survey.

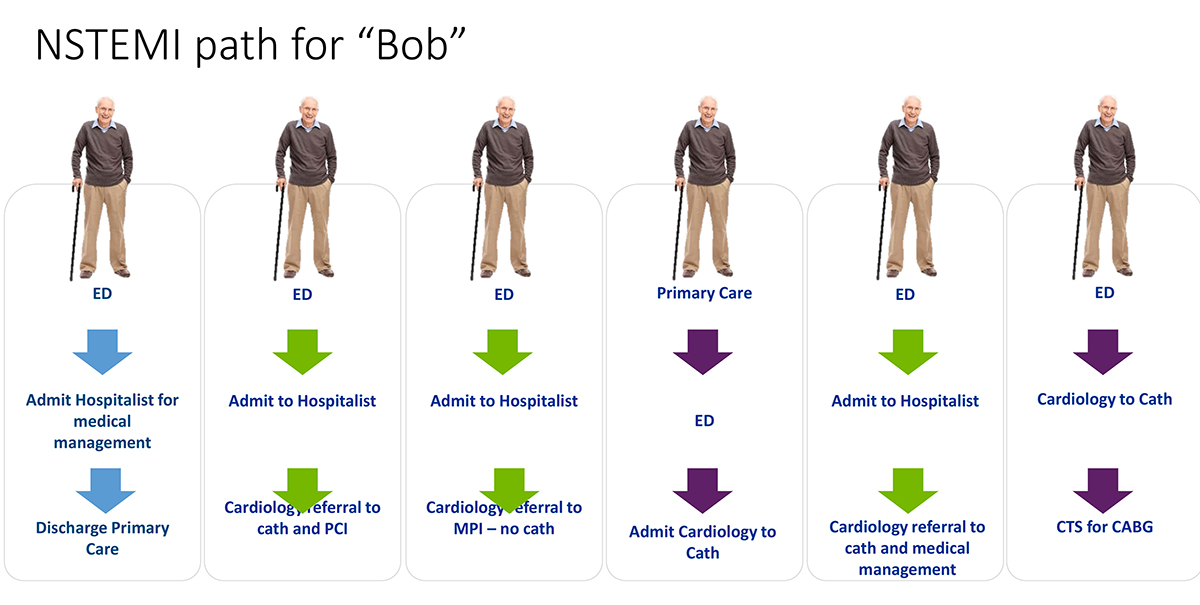

Through this consolidation, more and more care is delivered under a single banner or logo. However, despite the consistent name and visual, care today is still highly variable depending on which door of the institution the patient entered and by which providers render care. When you walk into a Starbucks Coffee — whether in Chicago or Seattle — you will find nearly identical tasting coffee and exceedingly consistent service. Starbucks has created standardized processes and protocols to ensure these outcomes. This outcome is not yet the case in majority of health care organizations, where individual location and personnel still play a significant role in what happens to our patient (Figure 3).

Patient centric care means that “Bob” (from the Figure 3 illustration) will receive the right care, at the right time and at the right location each time. Although this sounds simple and logical, it requires a fair amount of intent and focus to achieve. Less than half of care delivery has evidenced-based guidance, which means that an organization must develop a consensus around care for the majority. This takes time and will not happen without a commitment of resources to sit down and make it happen.

Through standardization we increase the likelihood that our patients will have a consistent experience, receive consistent clinical care and get the best outcomes within their clinical conditions all at the lowest cost option available. This last piece is critical in the value paradigm, where we must consider the cost of our care and not just the outcomes. While outcomes still matter, we have learned through data that similar results can be achieved with radically different cost structures.

Our standards must purposefully drive us toward the lowest cost options that meet our high expectations for quality and experience. In the era of high deductible plans and rising co-insurance amounts, our patients appreciate this stewardship. As an added bonus, these standards of processes and practice will also allow the most efficient utilization of expensive human and capital resources, reciprocating value to our own organization.

However, simply developing standards is not enough. Once in place, they must be intentionally implemented throughout the organization at every location. This requires training, education and meeting with all the affected constituents (who should have also been included in the development process). A tracking and monitoring system should also be instituted to ensure adherence and course correct as needed. Thus, the foundational need for the governance and leadership structure noted above.

Team is Recognized Over the Individual

Cardiovascular medicine, perhaps more than any other discipline, is deeply subspecialized and becoming more so over time. Interventional cardiology is becoming further compartmentalized with the advent of structural heart and medical cardiology has created a focus area around heart failure. Others are sure to come.

Given this subspecilaization and the complexity of skills required to be expert in each, patient centric care is about maximizing the efforts and efficiency of the overall cardiovascular team. Within the context of value, this can be simply stated as having the right clinicians seeing the right patient populations at the right time. For a complex heart failure patient, our infrastructure would systematically guide this individual to the heart failure team (or clinic) where care is tailored to his or her specific needs.

To achieve this goal, our operational infrastructure and provider reward systems must be designed in a way to promote the team over the individual, reducing or eliminating barriers that may impede this. For example, if our provider compensation plan relies exclusively or predominantly on individual production for individual compensation, the personal economics could influence the ceding of patients to the highest value care team and setting. This may particularly manifest itself at the margins, where there is not a bright line on whether that patient fits the requisite definition (e.g. “complex heart failure”). Another example is if our scheduling algorithms rely exclusively on time or established physician relationships, getting our patients to the optimal care setting may suffer.

Just like individuals need ongoing training and education to stay current in today’s health care environment, so to do our teams. Intentional and regular care team instruction should be institutionalized in our organizations, as opposed to simply relying on individual education bubbling its way up to the team. Even more advanced is the cross training that can occur between teams, with specific attention given to how our patients navigate not only within the complexity of the cardiovascular world but also through their broader health care needs entirely.

Highly Engaged With Data

Our health care organizations are rife with data. There are so much data that, as the saying goes, it can be like trying to drink from a fire hose (Figure 4). A wealth of valuable data can be found within our registries, where cardiovascular medicine is blessed with many highly-evolved peer databases. However, all too often these treasure troves of information are seen by only a select few and in sporadic, informal settings. This misses the power that these expensive and time-consuming resources can provide in our quest to improve the value — and therefore the patient centeredness — of our care.

An attribute of an organization committed to truly patient centric care is having an infrastructure where registry data are reviewed and acted upon in regular, structured and broadly engaged settings. This means that physicians beyond just the requisite medical director or committee chairs are part of the review process and likewise formulate the appropriate action plans. Relevant administrative and front-line staff are also part of the process, not only to provide the organizational horsepower to implement change but also to remain engaged in the constant process of performance improvement.

Since value in health care must consider cost, our data infrastructure must also consider financial information. Gone are the days when physicians were purposefully sheltered or insulated from the financial performance of their clinical care. In stark contrast, we must have an infrastructure that regularly and candidly puts financial performance — including margins — in front of our providers who either control or influence nearly 100 percent of these outcomes. If we do not accomplish this, it would be a huge miss in our quest for patient centric care.

Provider Compensation Syncs With Value

The third-party payment model in the U.S. health care system has traditionally been quite one dimensional; each service rendered generates a fee that is paid. This model is commonly referred to as a fee-for-volume system. Payment is not tied in any fashion to outcomes, quality, appropriateness, service or cost.

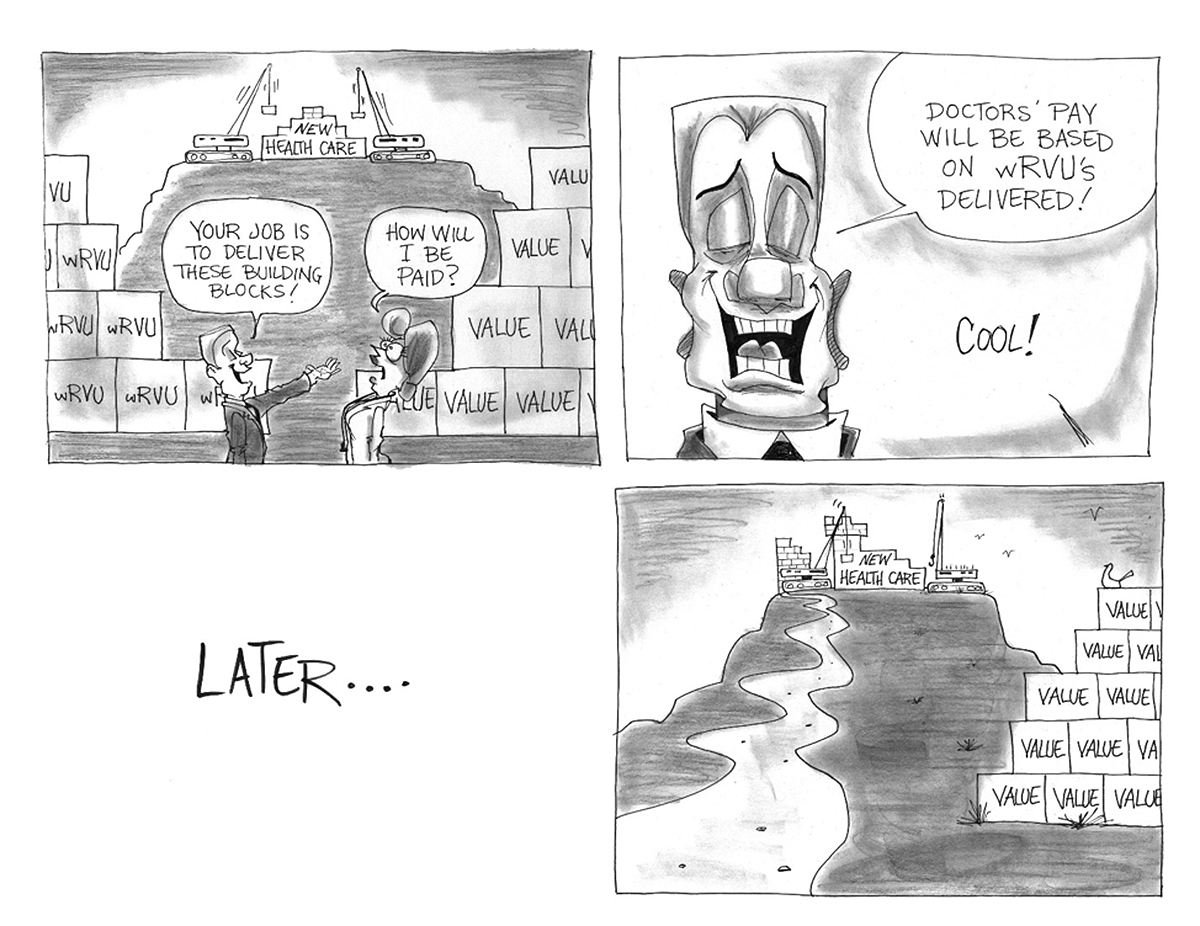

Somewhat frustratingly, this same payment system is largely intact today. However, it is changing and significant forces (Medicare, Amazon, Google, Walmart, etc.) are working hard to hasten the evolution. Delivering on value requires a very different set of skills and effort than providing clinical services, and our provider compensation must also evolve to recognize and promote these new activities. If we continue to pay one dimensionally such as on work relative value units — a very common model — we should not be surprised that value activities languish. This would be akin to paying a basketball player solely for personal points scored and then being frustrated with a low assist average.

Providers who embrace patient centric care recognize that rewards work and our compensation system needs to incent value. Responding to incentives is not evil; it is logical and appropriate. Thus, if we want and expect value — not just volume — we need to provide rewards for those activities that generate it. Even if we believe our providers will always do what is best for the patient, regardless of the compensation system in place, ignoring quality, cost and service in our individual reward system sends the wrong optics to the care team. Just as in our judicial system we work hard to avoid even the appearance of conflict, our compensation architecture likewise should shun the potential for misaligned priorities.

Accessible on All Fronts

Over the past several years, there has been a substantial increase in the number of non-traditional health care providers. Most have been focused on patient care that historically fell into the primary care purview such as the Walmart Care Clinic and CVS Minute Clinic, along with the plethora of new urgent care clinics and direct primary care centers. One of the most attractive features all of these offer is easy access, including not requiring scheduled appointments. In the case of direct primary care, patients are further guaranteed easy phone access to providers.

Cardiovascular medicine, as a specialty service, must not only be open to patients but also must create easy access for referring physicians. It is not good enough in today’s environment to rely on our ability to “work in” urgent patients. By definition, this implies some form of workaround to our normal processes such as a physician-to-physician phone call, which in turns means a more complicated and time-consuming process. Our referral base is also busy and does not have the time to negotiate availability for its patients, nor should we expect this to happen. Rather, our standard processes should seamlessly anticipate and accommodate the ebb and flow of urgent and routine patient visit needs.

Beyond the office, we must be electronically accessible to our patients. However, we have struggled in this area as witnessed by chronically low scores on CGCAHPS and HCAHPS patient surveys. The most common electronic communication tool is the telephone, so being accessible means answering the phone or providing an easy messaging platform with a timely return phone call. In 2018, patients further expect secure email and text message access to their providers, both for clinical information sharing (test results, prescriptions, questions, etc.) and for appointment scheduling — not just requesting an appointment but scheduling one entirely through a portal. Progressive groups are even providing fully electronic cardiovascular consults and follow-up visits. This accessibility is not only extremely convenient for out of town patients but is also an incredibly low-cost way to extend the reach of our cardiovascular provider resources into new geographies, outlying hospitals, skilled nursing facilities and beyond.

Moving even further on the spectrum toward patient centricity is offering non-urgent accessibility beyond the normal hours of Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. - 5 p.m. While this is attractive to all patients, it is especially valuable to our patients or family caregivers with jobs who have the added complexity of negotiating time off to attend appointments. This population also tends to be commercially insured, which is a critically important demographic from a payor mix standpoint.

Transitions are Intentional and Managed

We may provide outstanding care and achieve stellar marks for quality in our operating room or in the catheterization lab but if our patients leave without a clear understanding of what they need next and when, their care will languish. Transitions include ensuring that our patients are on the right medications, know who and when to see other physicians in their care regimen and have access to valuable ancillary resources as needed. These resources would include cardiac rehabilitation, home health care, nutritional guidance, psychiatric or psychological counseling, skilled nursing, transportation services and others. Medicare recognized the value of these transitions as it is now paying for them as part of the Transitional Care Management program and have made it a focus of programs like the Bundled Payment for Care Initiative.

To provide an example of intentional management of a patient care transition, let us imagine a heart failure patient named Rhonda who being discharged from the hospital. Her cardiologist wants to see her in the Heart Failure Clinic within five days of being released. However, because we investigated, we find that Rhonda already has an appointment scheduled with her primary care physician within that same window. Knowing that her primary care doctor will want to have the post-hospitalization plan of the clinic, we postpone that primary care visit for Rhonda so the plan is available at her next appointment.

Continuing our example, the Heart Failure Clinic makes sure that Rhonda’s primary care office has all the information it needs to follow and manage her care including testing results, lab works and an updated medication list. At the same time, care will be taken to make sure that an overload of unnecessary data is not piled on the primary office, thereby decreasing the likelihood of confusion. By managing her transition in this intentional way, we help Rhonda avoid duplication of services that both expose her to greater risk and increase her out of pocket costs, contributing to the focus on overall value.

Managing transitions and coordinating care between providers is hard work, causing its place near the top of our value and effort matrix. It is also an area that is still being negotiated in terms of who is responsible for what aspects of these logistical and clerical services. Although there is now some reimbursement available, the financial remuneration is still quite lacking. Organizations must find economical and efficient ways to provide these critical transitions.

Culture of Excellence

Organizations that truly espouse patient centeredness have excellence baked into every fiber of their collective being. The expectation for excellence is a given and part of the organizational DNA at every level. Decisions from leadership enforce and support this truth, in both good financial times and bad. Meetings of every stripe bake excellence into every agenda. When conversations or planning stray toward mediocrity, the group naturally brings it back to a focus on excellence.

While culture is a very qualitative aspect of a company’s makeup, we have either worked in or visited organizations that get it — and those that do not. Excellence manifests in the day-to-day, mundane and seemingly unimportant work and at every level of our human resources, regardless of paygrade or title. When the expectation for excellence is ubiquitous, our organization is truly poised to provide patient centric care. There is no doubt that significant effort will still be required, but we will not have to fight battles within.

Conclusion

The overall value of the health care we deliver increases significantly when we provide it in a patient centric fashion. From outcomes to cost to experience, all aspects improve when we provide care at all levels through the lens of the patient. This is not an easy endeavor, with numerous moving and complicated parts and the current payment system lagging in terms of funding it. However, we must continue to forge ahead because our patients deserve and increasingly expect it — and so would we.

If this is not enough motivation, new competitors have recognized opportunities where we missed on patient centricity and are actively working to disrupt the industry. While they may still be nibbling at the margins with little to no direct impact, that fulcrum often falls quickly. In addition, our largest payor for cardiovascular service, Medicare, is continuing to shift reimbursement to the overall value delivered. Providing patient centric care increases our likelihood of success through this transition.

True patient centric care is more than one or two case examples; it must be a way of life, embedded in our organizational DNA. Achieving it is neither quick or easy, but the prize for all of us is worth it.

This article was written by Joel Sauer, vice president of MedAxiom Consulting in Neptune Beach, FL.