A Day in the Life of an Early Career Cardiologist in Canada

Before reading my story below, there is a limitation that readers should be aware of: The experiences described reflect my reality as an early career cardiologist, and may not be generalizable to other individuals or health care settings. They may also not accurately represent all the days in my schedule.

However, the following is based on real events, and days like this happen quite frequently. In fact, I would say that it is quite reflective of a typical "day in the office."

I hope that many early career cardiologists (and probably others at later stages, as well) see some parallels to their daily practices.

In order to understand my "typical" day, it is essential to list some of my professional activities and responsibilities. I work in an academic tertiary care center in Montreal, Canada, where my area of focus is cardiac intensive care.

I am in the cardiac intensive care unit slightly more than one week out of every four. When I am not in the cardiac intensive care unit, approximately half of my time is protected research time. "Protected" means that I am often asked by colleagues to help out with clinical shifts, as I am listed on "research."

As a result, many evenings and weekends, spare moments during the day, plane flights, etc., are my time for research.

I see patients in my outpatient clinic about once day per week, cover stress tests and have an assortment of nonclinical duties (i.e., director of cardiology quality of care and involvement with national organizations).

At the time of writing this, I was covering the cardiac intensive care unit. Sign-in starts at 7:30 a.m., but the day really started earlier for me. I was on call the night before, so, while I did not need to come into the hospital, I was dutifully woken up several times to discuss cases.

My infant son made sure that any attempt to sleep between the calls were not realized. Plus, my heart pounded and my mind raced several times during the night.

Did I make the right clinical decisions?

Can I really trust the bedside echo report from the resident?

Should I have gone in?

After signing in, I provide a didactic teaching session for 30 minutes on my favorite topic: cardiogenic shock.

During the talk, I am interrupted by my research assistant who has identified patients for a clinical trial. I receive a text from a colleague asking a question. My phone vibrates from a call, to which I tap ignore.

We round in the cardiac intensive care unit, then on the cardiac ward. I do some bedside teaching around the cases. Typical stuff: acute coronary syndromes, atrial fibrillation management, acute heart failure, etc.

We pause to discuss an interesting cardiomyopathy case. During these three hours, there are countless interruptions from bedside nurses, clinical pharmacists, other physicians and research assistants.

Following rounds, we quickly run through the list and the house staff scatter to start their admissions and perform their tasks.

I retreat to my office.

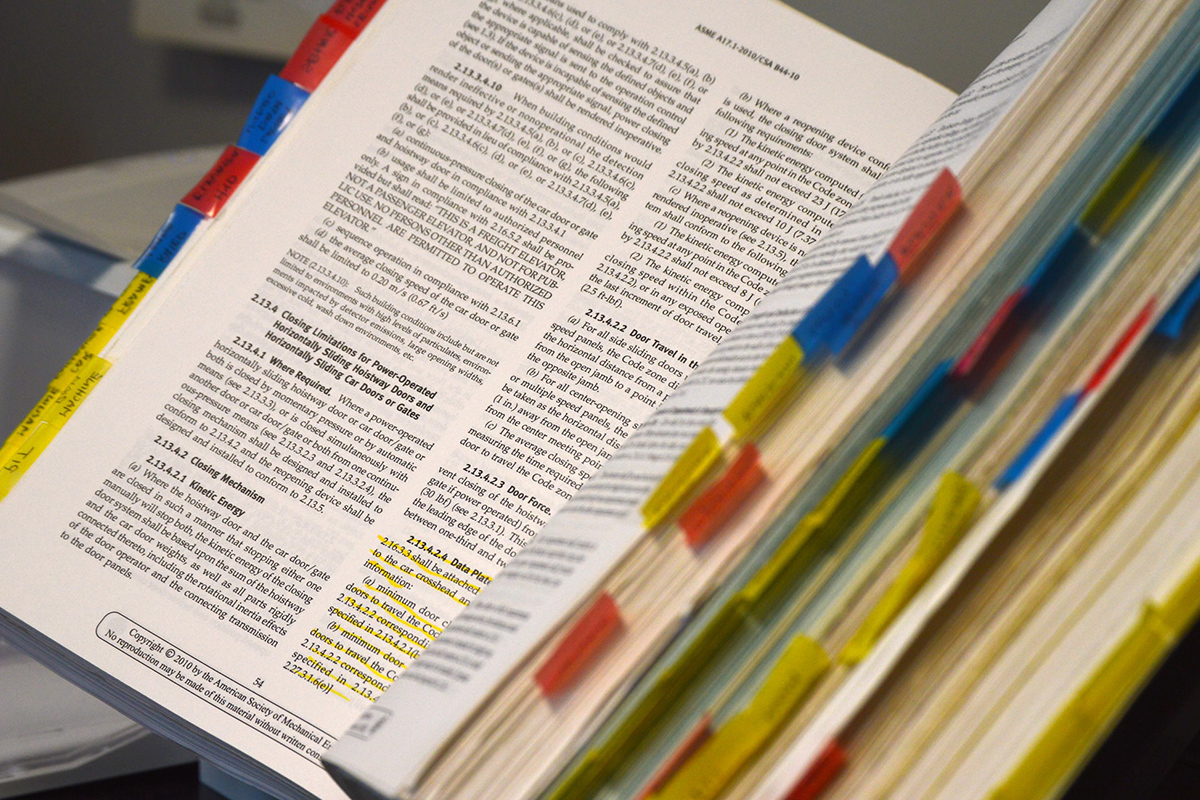

Three folders await me in the box outside my door. A blue one from my secretary with urgent test results that have not yet been scanned in and a red one from my research assistant of documents to sign.

I dutifully go through the folders. Then, I go through the to-do section of my electronic medical record.

I check my email – about 40 emails just this morning. Only about five that are important (although none are very important), and I flag the essential ones to reply to later. I fire off some quick replies, as well.

At my desk, I sit down to work on a revision to a manuscript following peer-review. As soon as I start, the bombardment begins. My pager vibrates – an outside pharmacist wants to clarify a resident's prescription.

A knock at the door from a student looking to do research with me.

I grab a quick bite at my desk while perusing abstracts of the latest issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. A colleague stops by to ask a question.

The residents notify me that they are ready to review their admissions. I shut down my computer and return to the unit. We review the admissions, deal with a couple of urgent situations, review the day's cardiac imaging tests and then meet for sign-out.

The day passed in the blink of an eye.

I go home to be my most important role: a husband and dad. But I know that there will be emails to respond to and paperwork to finish up later.

And the cycle repeats.