Cover Story | Cardiovascular Risk Reduction

The increasing burden of cardiovascular disease, along with rising costs, is driving a renewed focus on cardiovascular disease risk reduction. More and more, prevention and population health are in the spotlight in scientific meetings and journals. This high-value, high-return approach to addressing cardiovascular disease has the potential to prevent at least 200,000 deaths from heart disease and stroke each year in the United States.1 Depending on the geographic region, age-adjusted preventable cardiovascular death rates range from 18 to 182 per 100,000 people.1 Experts agree that health care providers need to focus on preventive and lifestyle aspects of cardiovascular care to promote individual and population health.

Cardiovascular disease risk reduction revolves around the major risk factors, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia and diabetes. Although some risk factors, such as age and hereditary factors cannot be modified, lifestyle modification is key to preventing cardiovascular disease. Risk assessment analyses have shown that lifestyle-related risk factors are the major causes of death and disability in the U.S. and the world. A heart healthy diet, regular physical activity, smoking cessation and maintaining a healthy weight comprise the foundation for cardiovascular disease risk reduction.

Hypertension

Hypertension is the number one cardiovascular risk factor and the world’s greatest risk factor for death and disability, according to the World Health Organization. Approximately 85.7 million U.S. adults 20 years of age and older have hypertension, with the highest rates in African Americans.2 From 2003 to 2013, the number of deaths attributable to hypertension increased by 34.7 percent. People with hypertension are three-times more likely to die from heart disease and four-times more likely to die from stroke.3

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), from 2009 to 2012, hypertension was controlled among 54.1 percent of people with hypertension, 76.5 percent were currently treated, 82.7 percent knew they had hypertension and 17.3 percent were undiagnosed.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend a three-pronged approach to blood pressure control.3 Health care systems should use electronic health records (EHRs) and patient registries to identify and control hypertension. Health care providers should use a team-based approach, check blood pressure at every visit and simplify treatment (once-a-day doses; fewer pills). Blood pressure control improves when patients comply with medications, measure their blood pressure, eat a healthy low sodium diet, increase physical activity, maintain a healthy weight, limit alcohol use and avoid smoking.

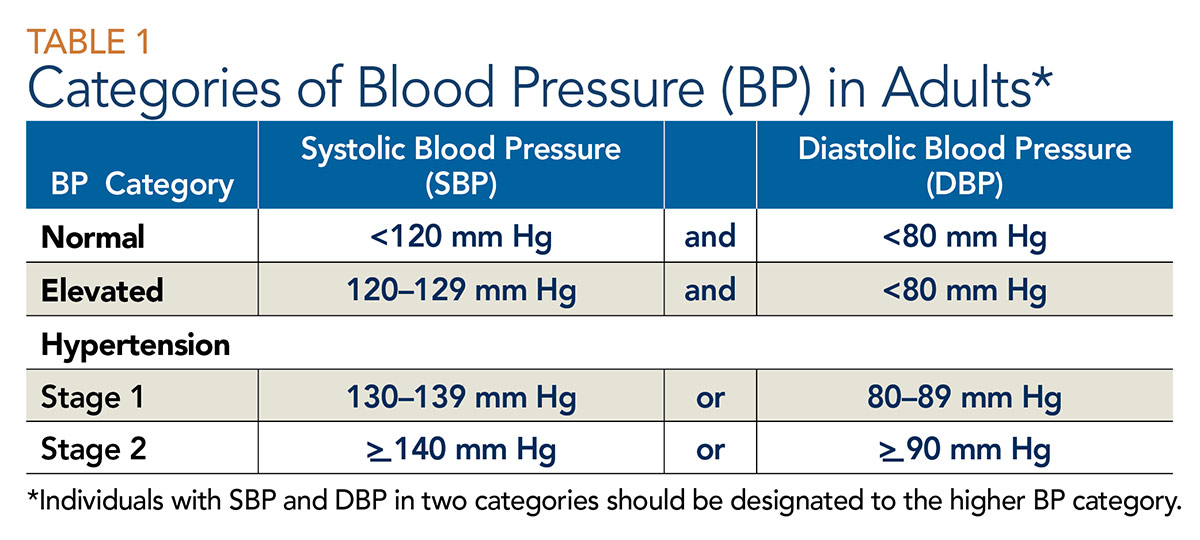

The new clinical practice guideline for high blood pressure from the ACC and American Heart Association recommends 10-year risk assessment for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) to guide treatment, along with strategies to improve hypertension treatment and control, proper blood pressure measurement and structured, team-based approaches to care.5 The threshold for treatment is determined by the ASCVD risk assessment. For the vast majority of patients with stage 1 hypertension, the initial recommended action is one or more nonpharmacological interventions. Table 1 defines the categories of blood pressure in adults.

ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus App

The ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus App uses recent science and user feedback to help a clinician and patient build a customized risk-lowering plan by estimating and monitoring change in 10-year ASCVD risk. This app can be used to estimate a patient’s initial 10-year ASCVD risk; receive an individualized, risk-based, intervention approach; project the impact of specific interventions on a patient’s risk; guide clinician-patient discussion around customizing an intervention plan; update risk at follow-up based on a patient’s response to therapy. Click here to download the app.

Dyslipidemia

High cholesterol, present in nearly one in three U.S. adults, is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. In 2011 to 2012, the targets for total cholesterol were met in 75.7 percent of children (<170 mg/dL) and 46.6 percent of adults (<200 mg/dL). Declining cholesterol levels in recent years are attributable to greater use of cholesterol-lowering drugs rather than dietary changes.4 These gains are primarily due to the use of statins. Recently, PCSK9 inhibitors produced striking reductions in LDL-C that, in the long term, reduced the incidence of subsequent coronary events in people with existing coronary disease and alirocumab reduced mortality in ODYSSEY Outcomes. Still, adding lifestyle components that incorporate dietary changes and physical activity, even when cholesterol is controlled with medications, promotes lifestyle changes that also contribute to long term-health, longevity and well-being. The Million Hearts Program recommends limiting saturated and trans fats and increasing fiber in the diet, getting regular physical activity, maintaining a healthy weight and smoking cessation.6

Diabetes

One in 10 U.S. adults has diabetes and 90 to 95 percent of cases are type 2 diabetes. Type 2 diabetes disproportionately affects minorities and is increasingly common among children and adolescents.4 Diabetes is associated with a two- to three-fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease, which is more likely to be the cause of hospitalization in patients with diabetes than diabetes-related causes. Experts recommend prevention of cardiovascular events as the goal of diabetes treatment.

Two new classes of drugs — sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists — have been shown to reduce cardiovascular events, beyond their glucose-lowering benefit. The American Diabetes Association recommends lifestyle management in addition to medications for the management of diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors, including nutrition therapy, physical activity and smoking cessation.7

Bove’s Brief: Putting it Into Practice

- Talk to your patients – remember to clearly state the importance of the lifestyle measures for prevention and that together you’ll monitor progress. Explain the relationship between a drug treatment and the impact on heart health.

- Set clear goals and write them down for the patient to take home. Goals should include weight reduction, glucose control, lowering LDL-C, healthy diet and a prescription for physical activity.

- Engage the team, including physician assistant, nurse practitioner, nurse and behavior coach, to work with patients to reach their specific goals.

- Remind your patients – vape is as harmful as tobacco and excess alcohol negatively affects heart health.

Diet

Poor diet is the leading risk factor for death and disability in the U.S. and was responsible for 678,000 deaths from all causes in 2010. Insufficient intake of fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds, whole grains, and seafood, as well as excess sodium intake are considered major contributors.4 In fact, the best improvements in heart health through risk factor reduction have been seen with a predominantly plant-based diet that emphasizes green, leafy vegetables, whole grains, legumes and fruit. Limitation of dietary cholesterol is also recommended.

Numerous observational studies have demonstrated the benefit of a Mediterranean style diet on cardiovascular risk reduction. The PREDIMED trial showed that a Mediterranean diet with increased mixed nuts or substitution of extra-virgin oil for regular olive oil reduced cardiovascular events by 30 percent.7 While this is exemplary, it represents a 70 percent persistence of events, with residual risk reduction opportunities through further refinement of diet.8

A Mediterranean diet typically consists of:

- Olive oil as the culinary fat

- Abundant fresh vegetables and fruits

- Grains

- Legumes

- Tree nuts

- Aromatic spices and herbs

- Frequent intake of fish and shellfish

- Moderate consumption of wine with meals

- Low intake of meat and animal products and simple sugars

Studies have found that the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet with sodium restriction has beneficial effects on cardiovascular risk factors.9 Results from the DASH-Sodium trial showed that the combined effects of the low-sodium DASH diet vs. the high sodium-control diet on systolic blood pressure ranged from –5.3 to –20.8 mm Hg.

The DASH eating plan recommends:

- Eating vegetables, fruits and whole grains

- Including fat-free or low-fat dairy products, fish, poultry, beans, nuts and vegetable oils

- Limiting foods high in saturated fats, such as fatty meats, full-fat dairy products, and tropical oils such as coconut and palm oils

- Limiting sugar-sweetened candies and beverages

However, it should be noted that large prospective data sets warn that consumption of any source of animal protein, including fish studied in DASH and PREDIMED, increases cardiovascular and overall mortality relative to vegetable protein sources in patients with at least one cardiac risk factor,10 albeit with a large substitutionary benefit over red meat and processed red meat.11

Physical Activity

The benefits of physical activity in addition to a healthy diet for prevention of heart disease have long been recognized. Despite these benefits, three of 10 U.S. adults report being inactive during their leisure time and only half report aerobic exercise levels consistent with national guidelines. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends intensive behavioral counseling to promote physical activity for people with cardiovascular risk factors and those with cardiovascular disease.

The PURE study found that just 30 minutes of physical activity five days a week could prevent one in 12 deaths and one in 20 cases of cardiovascular disease worldwide.12 A higher reduction was seen in those who were highly active (750 minutes weekly). The PURE study also found that physical activity incorporated into daily life had the same benefit as leisure activities. From the STABILITY trial, we learned that walking at a brisk pace for as little as 10 minutes a day or at a slower pace for 15 to 20 minutes can reduce all-cause mortality by 33 percent in patients with stable coronary heart disease.13

Although gains have been made, cardiovascular disease reduction through lifestyle modification remains a challenge. Most Americans continue to lead an unhealthy lifestyle and less than one percent of Americans meet ideal levels of seven key cardiovascular health metrics (blood pressure, physical activity, cholesterol, healthy diet, healthy weight, smoking status, blood glucose). Some obstacles to achieving healthy lifestyle patterns include limited health care provider training on healthy diets and the need for physical activity, lack of access to adequate healthw care, high cost of health care, prior authorization of medications, limited time with patients and patient adherence to lifestyle modifications.

Better cardiovascular health will require an expanded focus on cardiovascular disease prevention and promotion of healthy behaviors across the entire lifespan. Approaches that target lifestyle and treatment at the individual level are needed, along with health care system approaches that encourage, facilitate and reward efforts by patients and providers to improve health behaviors and factors; and population-level approaches that target lifestyle and treatment in schools and workplaces, local communities, states and the nation.

More Insights on Risk Reduction from ACC.18

Another benefit of physical activity appears to be lowering high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels. A study by Marcio Sommer Bittencourt, MD, FACC, and colleagues in Brazil showed that persistent exercise maintains this benefit over time. In 5,261 adults (20 percent women) undergoing routine health screening, they collected clinical characteristics and self-reported physical activity level at baseline and after a median of 2.9 years. Participants who had a persistent high level of physical activity had a 65 percent lower risk of elevated hsCRP (defined as ≥3 mg/L) and this benefit was seen in men and women.

In the Medicare population in cardiology practices, about one in eight patients has a 10-year risk greater than 30 percent for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), using the Million Hearts model in a PINNACLE registry population, and thus qualify as high risk. In the population of 135,166 patients, the mean ASCVD risk was 41.9 percent. The study by William Borden, MD, FACC, et al., showed this risk was lowered by nearly 10 percent when targeting the three main modifiable risk factors of blood pressure, dyslipidemia and smoking to levels achieved in clinical trials. Each component lowered risk by 3.3 percent, 6.3 percent and 0.5 percent, respectively. These reductions were achievable – with 73 percent of the cardiology practices achieving risk reductions between 5 and 10 percent in their patient populations and 27 percent achieving risk reductions that were ≥10 percent.

Combining real-world evidence and study data revealed a potential for better management of cardiovascular risk factors in African Americans with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and uncontrolled hypertension. Using data from the large outpatient Diabetes Collaborative Registry, Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, FACC, et al., found that 33 percent of the 161,097 African American patients in the registry had uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg). Further, they found that only 2.7 percent of these patients were being treated with an SGLT-2 inhibitor, based on eligibility for the 1245.29 study. The study, conducted in African Americans with T2D and uncontrolled hypertension, showed that empagliflozin vs. placebo produced a 5 mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure and a 0.8 percent reduction in HbA1c. Potentially these patients are candidates for empagliflozin, and other SGLT-2 inhibitors if found to be a class effect, for treatment of hyperglycemia and hypertension.

This article was authored by Kim Allan Williams Sr, MD, MACC; Sarah Alexander, MD, FACC; and Hena Patel, MD. For more topical articles in cardiovascular medicine, visit the Medscape and ACC Center of Excellence collection at Medscape.com.

References

- CDC. Vitalsigns: Preventable Deaths from Heart Disease & Stroke. 2013. (Available here)

- AHA. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics–2017 Update. Published January 25, 2017.

- CDC. Vitalsigns: Getting Blood Pressure Under Control. 2012. (Available here)

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin E, Go AS, et al. Circulation 2015;133:e38-e360.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;Nov 7:[Epub ahead of print].

- Million Hearts: Meaningful Progress 2012-2016 A Final Report. CDC. May 2017.

- American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care 2018;41, Supplement 1.

- Yokoyama Y, Nishimura K, Barnard ND, et al. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:577-87.

- Hu FB, Cespedes Feliciano EM. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:815-17.

- Song M, Fung TT, Hu FB, et al. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1453-63.

- Pan A, Sun Q, Berstein AM, et al. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:555-63.

- Lear SA, Hu W, Rangarajan S, et al. Lancet 2017;390:2643-54.

- Stewart RAH, Held C, Hadziosmanovic N, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1689-1700.

Clinical Topics: Anticoagulation Management, Cardiovascular Care Team, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Prevention, Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia, Lipid Metabolism, Nonstatins, Novel Agents, Statins, Diet, Exercise, Hypertension, Smoking

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, American Heart Association, Antibodies, Monoclonal, Benzhydryl Compounds, Blood Pressure, Blood Pressure Determination, Cardiovascular Diseases, Cause of Death, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S., Cholesterol, Cholesterol, Dietary, Coronary Disease, Counseling, C-Reactive Protein, Dairy Products, Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2, Diet, Mediterranean, Diet, Sodium-Restricted, Dyslipidemias, Electronic Health Records, Exercise, Fabaceae, Factor IX, Factor X, Follow-Up Studies, Fruit, Glucagon-Like Peptide 1, Glucose, Glucosides, Glycated Hemoglobin A, Health Personnel, Heart Diseases, Hospitalization, Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors, Hypercholesterolemia, Hyperglycemia, Hypertension, Leisure Activities, Longevity, Medicare, Monosaccharides, Nurse Practitioners, Nutrition Surveys, Outpatients, Physician Assistants, Prospective Studies, Registries, Risk Assessment, Risk Factors, Risk Reduction Behavior, Smoking, Smoking Cessation, Stroke, Sweetening Agents, Symporters, Weight Loss, ACC18, ACC Annual Scientific Session

< Back to Listings