Telehealth and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: A Discussion of the Why and the How

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to disruption in every aspect of cardiovascular care delivery. After the initial wave of COVID-19 infection subsides, subsequent surge(s) of acute cardiovascular disease (CVD) presentations are expected due to the "double hit" from suspended clinic visits/elective procedures and delays in seeking timely care from patients' fears and misconceptions of quarantine orders.1 The adverse impact on cardiovascular care delivery and outcomes will likely be long-lasting if our health systems do not adapt quickly and efficiently. In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, a tremendous opportunity arises for implementation and development of primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention via telehealth platforms.

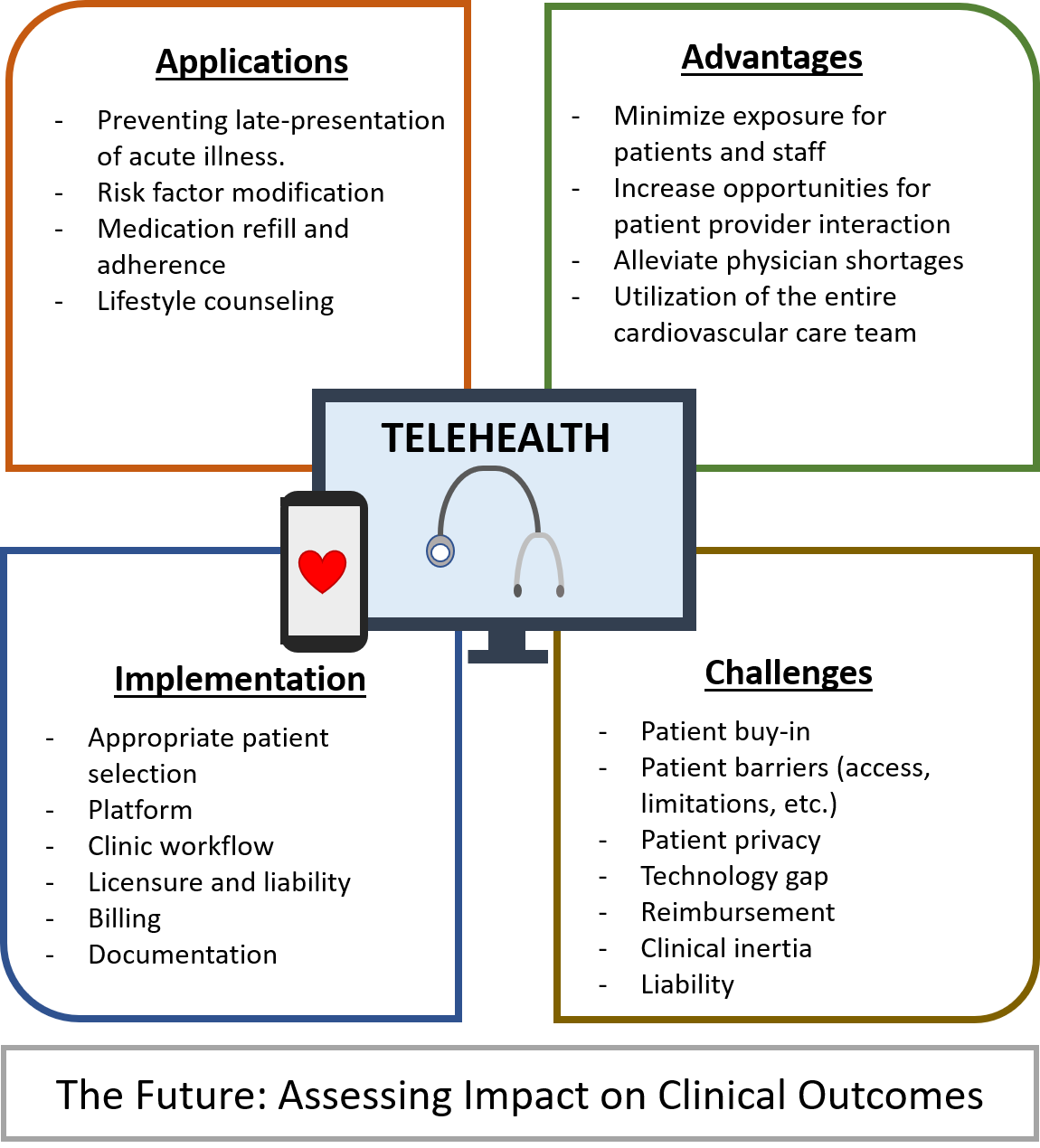

Telehealth encompasses, but is not limited to, real-time consultation using audio/video communication technology instead of in-person visits, as well as mobile health and telemonitoring. Medical services in CVD prevention are particularly well suited for transitioning to telehealth platforms as interventions are centered largely on counseling and are most effective with regular check-ins (in-person or virtual) to reinforce good prevention practices (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Current data have demonstrated higher risk for COVID-19 related morbidity and mortality in individuals with pre-existing CVD and cardiometabolic risk factors.2 Therefore, timely delivery of CVD prevention services, which may be implemented virtually, can help modify risk factors associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients infected with COVID-19. Moreover, CVD prevention can help alleviate pressure on hospitals by reducing acute presentation of CVD among non-COVID-19 individuals.

Another major focus for providers will be long-term risk reduction of CVD. The management of chronic diseases such as hypertension or diabetes mellitus most effectively involves regular interactions between a provider and patient that reinforce adherence to lifestyle and medication interventions, and provide opportunities to make necessary adjustments based on objective biometric data provided by patients (i.e. blood pressure measurements or blood glucose readings). Prior studies among patients with hypertension and diabetes have demonstrated that self-monitoring, when coupled with counseling/tele-counseling, web/phone-based feedback and education resulted in clinically significant improvement of blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C).3,4 In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, when routine clinic visits are often delayed or canceled, the impact of telehealth interventions for risk factor modification may be even greater. Barriers for patients to utilize telehealth may include limited resources or limited health literacy and for the geriatric population, facility with electronic communication platforms as well as impaired vision or hearing, which can make virtual communication difficult. Special considerations must be taken to address delivery of care in these at-risk populations.

As with in-person counseling, lifestyle counseling regarding diet, physical activity, and weight loss can also be readily performed on telehealth platforms. Such interventions should be specific and personalized, accounting for potential socioeconomic barriers or physical limitations. Telehealth may enhance understanding of socioeconomic barriers to care by allowing the provider a glimpse directly into the patient's home. For instance, tele-visits facilitate the opportunity to speak with family members and caregivers, which can provide additional insight into patients' health. Additionally, virtual visits make it easier for practitioners to more thoroughly and accurately review prescription medications as well as over-the-counter or herbal therapies that a patient is taking rather than relying on patients' memory or incomplete medication lists during an office visit. Incorporation of mobile health (mHealth) technology, especially coupled with virtual visits and use of at-home monitoring devices, can further augment traditional counseling – providing a reliable source of health information, a medium for users to set personal goals, and allowing for real-time tracking of progress, all of which can enhance self-motivation, accountability and disease management. Indeed, the use of mHealth interventions has been associated with improvement in cardiometabolic risk factors including blood pressure, LDL-C, smoking, physical activity and body mass index.5 Given that mobile devices are nearly ubiquitous in our society, the integration of mHealth into CVD prevention practices has the potential for widespread impact on patient outcomes and on clinical research. Data from a nationally represented sample of 3,248 adults in the United States demonstrate that while a majority of individuals with CVD risk own a smartphone (73%), there remains room for growth for mHealth uptake (48%).6

Another area of importance that can be addressed by telehealth is medication refill and adherence. Routine clinic visits afford clinicians the opportunity to evaluate and reinforce medication adherence, make necessary adjustments, and refill medications. In the setting of delayed or canceled in-person appointments, virtual visits can serve as a buffer to ensure that patients continue to have access to and are adherent to their medications. Furthermore, telehealth can better accommodate patient care that leverages the entire cardiovascular team including physicians, advanced-practice providers, pharmacists, dieticians, among others. Moreover, such an approach can help alleviate pressure placed on health systems due to physician shortages in areas of need as related to COVID-19.

While there remain some barriers, changes in healthcare regulations and reimbursement have greatly facilitated the implementation of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic and incorporation into electronic medical records. The Department of Health and Human Resources has amended regulations to allow for telehealth visits over non-HIPAA compliant platforms such as Zoom or Skype, though many of these platforms now offer HIPAA compliant versions.7 The Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and many larger payers have expanded their reimbursements of telehealth visits. Additionally, telephone only visits, which have previously not been covered, are now reimbursable during the public health emergency.

When implementing telemedicine, providers must familiarize themselves with the liability, licensure, billing and documentation requirements as pertaining to their individual practice. To facilitate workflow, providers may consider setting aside a block of time for scheduled tele-visits and coordinate with patients prior to the visit to ensure availability and ascertain familiarity with the communication platform. Ultimately, it is essential for providers to select the appropriate patients for telehealth visits. Patients who are acutely ill may need to be triaged to the hospital. Likewise, patients with more complex medical conditions in addition to their prevention care needs may need to be re-directed for an in-person visit. In the truest spirit of CVD prevention, providers can utilize telehealth platforms to discern alarming symptoms and to counsel patients on the risks of delaying medical care.

Telehealth has provided clinicians a temporary recourse to continue delivering high-quality medical care to patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. For CVD prevention, however, the amplified interest in telehealth among providers and expansion in coverage by insurance has aligned to create a rare opportunity to improve care delivery. Clinicians, health systems and public policy makers should continue to build upon this momentum to incorporate telehealth care delivery into CVD prevention practices long-term.

References

- Bhatt AS, Moscone A, McElrath EE, et al. Declines in hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicenter tertiary care experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:280-8.

- Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, et al. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2020;141:1648-55.

- Tucker KL, Sheppard JP, Stevens R, et al. Self-monitoring of blood pressure in hypertension: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002389.

- Shea S, Weinstock RS, Teresi JA, et al. A randomized trial comparing telemedicine case management with usual care in older, ethnically diverse, medically underserved patients with diabetes mellitus: 5 year results of the IDEATel study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:446-56.

- Chow CK, Redfern J, Hillis GS, et al. Effect of lifestyle-focused text messaging on risk factor modification in patients with coronary heart disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;314:1255-63.

- Shan R, Ding J, Plante TB, Martin SS. Mobile health access and use among individuals with or at risk for cardiovascular disease: 2018 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e014390.

- Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth Remote Communications During the COVID-19 Nationwide Public Health Emergency (HHS.gov website). 2020. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/. Accessed 07/28/2020.

Clinical Topics: COVID-19 Hub, Dyslipidemia, Prevention, Lipid Metabolism, Nonstatins

Keywords: Primary Prevention, Secondary Prevention, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Infections, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Cholesterol, LDL, Risk Factors, Blood Glucose, Medicare, Medicaid, Hemoglobin A, Electronic Health Records, Medication Adherence, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, Blood Pressure, Health Literacy, Cardiovascular Diseases

< Back to Listings