The Role of the Posterior Left Pericardiotomy in Reducing Pericardial Effusion and Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation After Cardiac Surgery

Quick Takes

- A significantly higher incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) has been found in patients developing pericardial effusion following cardiac surgery.

- The highly pro-oxidant and proinflammatory milieu caused by the presence of shed mediastinal blood within the pericardial space might act as a trigger for POAF.

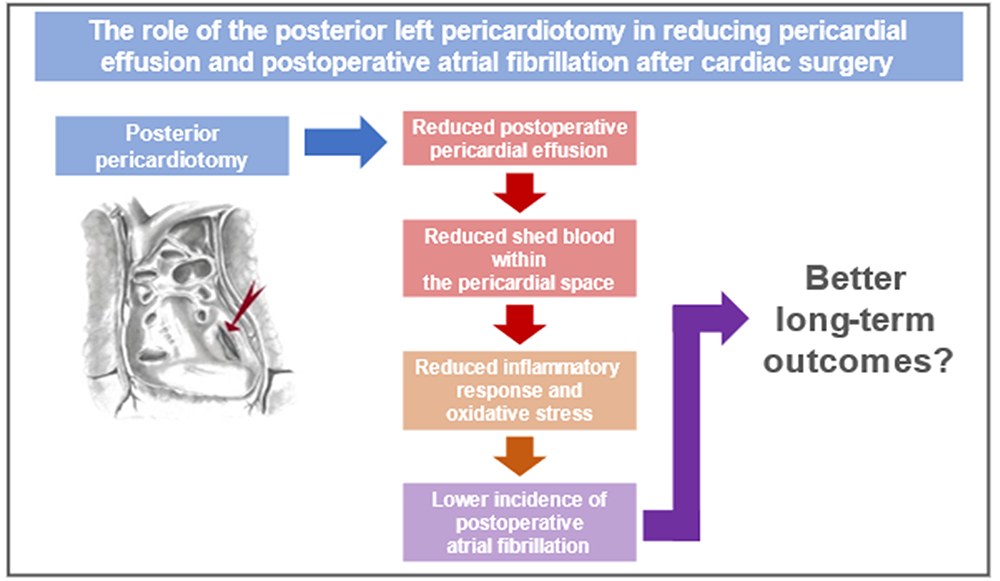

- Posterior pericardiotomy significantly reduces the incidence of POAF by minimizing the amount of blood retained within the pericardium.

Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation (POAF) and Pericardial Effusion: A Dangerous Liaison

POAF represents the most frequent complication in patients undergoing cardiac surgery,1 with an estimated incidence ranging from 19% to 30%.2-4 Rather than acting as an innocent bystander, its occurrence has been associated with major adverse outcomes, including higher rates of mortality, stroke, heart failure, hospitalizations and costs.3,5 Circumstantial evidence of an association between POAF and postoperative pericardial effusion initially came from three observational studies conducted between 1980 and 1990.6-8 These preliminary findings were subsequently confirmed in a prospective echocardiographic series of 150 cardiac surgical patients by Ikäheimo and colleagues who reported a significantly higher incidence of postoperative atrial arrhythmias among patients undergoing cardiac surgery who developed postoperative pericardial effusion (27% vs. 11% in patients with no pericardial effusion; p<0.05).9

Pericardial Effusion, Inflammation and POAF: What Do We Know?

An increasing amount of evidence suggests that shed mediastinal blood within the pericardial space might have a pivotal role in the development of a highly pro-oxidant and proinflammatory milieu that can trigger POAF through breakdown products, activation of the coagulation cascade, and oxidative burst.4 Such observations have also been indirectly supported by a number of studies showing that surgical drainage of the pericardium in the postoperative period could reduce POAF incidence.10,11

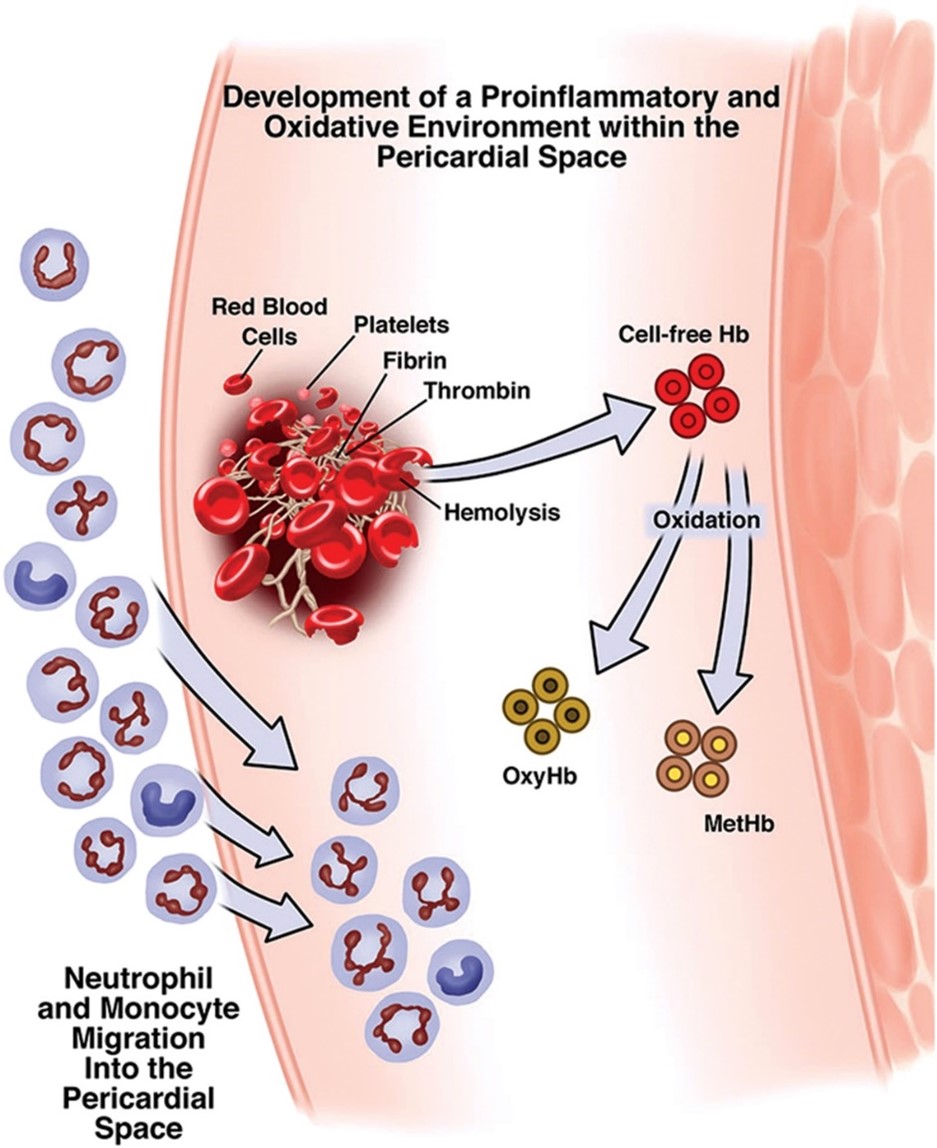

Three factors seem to act as main drivers in the development of such procoagulant and proinflammatory environment within the pericardium: cardiopulmonary bypass, operative trauma, and hemolysis. The first two operate in combination, prompting local recruitment and activation of neutrophils. Hemolysis occurs postoperatively, causing the release of cell-free hemoglobin, which is quickly oxidized to methemoglobin, ultimately recruiting neutrophils into the pericardial space from the surrounding vasculature (Figure 1). Oxidative stress by reactive oxygen species generated by activated neutrophils and leukocytes leads to lipid peroxidation that damages the left atrial surface and peri-atrial epicardial fat pads, eventually triggering POAF.4

Figure 1

Strategies to prevent shed mediastinal blood from accumulating into the pericardial space, either through placement of additional chest tubes or posterior pericardiotomy, have therefore been considered to reduce POAF incidence.

Posterior Pericardiotomy for Prevention of POAF

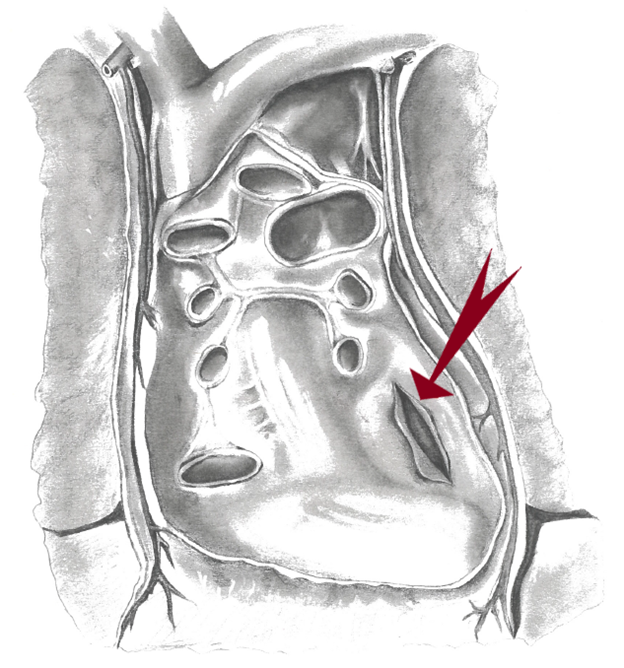

First described by Mulay et al.,12 posterior pericardiotomy is a safe and simple surgical technique consisting in a 4 to 5 cm longitudinal incision of the posterior pericardium, parallel and posterior to the phrenic nerve, extending from the left inferior pulmonary vein to the diaphragm, and allowing drainage of the pericardial fluid into the left pleural space (Figure 2). The authors observed that while posterior pericardiotomy was able to reduce the incidence of pericardial effusion (8% vs. 40% in patients receiving vs. those not receiving posterior pericardiotomy, respectively; p<0.001), it also reduced the occurrence of supraventricular arrhythmias (8% vs. 36%, respectively; p<0.005).12 Additional technical details to safely perform this procedure have been recently described.13

Figure 2

Reducing Postoperative Pericardial Effusion Reduces POAF: Evidence from Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

Following these encouraging results, several RCTs have tested the use of posterior pericardiotomy for POAF prevention (mainly in the setting of coronary artery bypass surgery), with the majority reporting a significant reduction of POAF in patients receiving posterior pericardiotomy. These findings have been corroborated by a meta-analysis including 3,425 cardiac surgical patients, which showed that surgical drainage of the posterior pericardium was associated with a reduction of the odds of POAF by 58% (p<0.001).10 However, the methodologic quality of the available trials was generally medium-low, and many were also statistically underpowered.

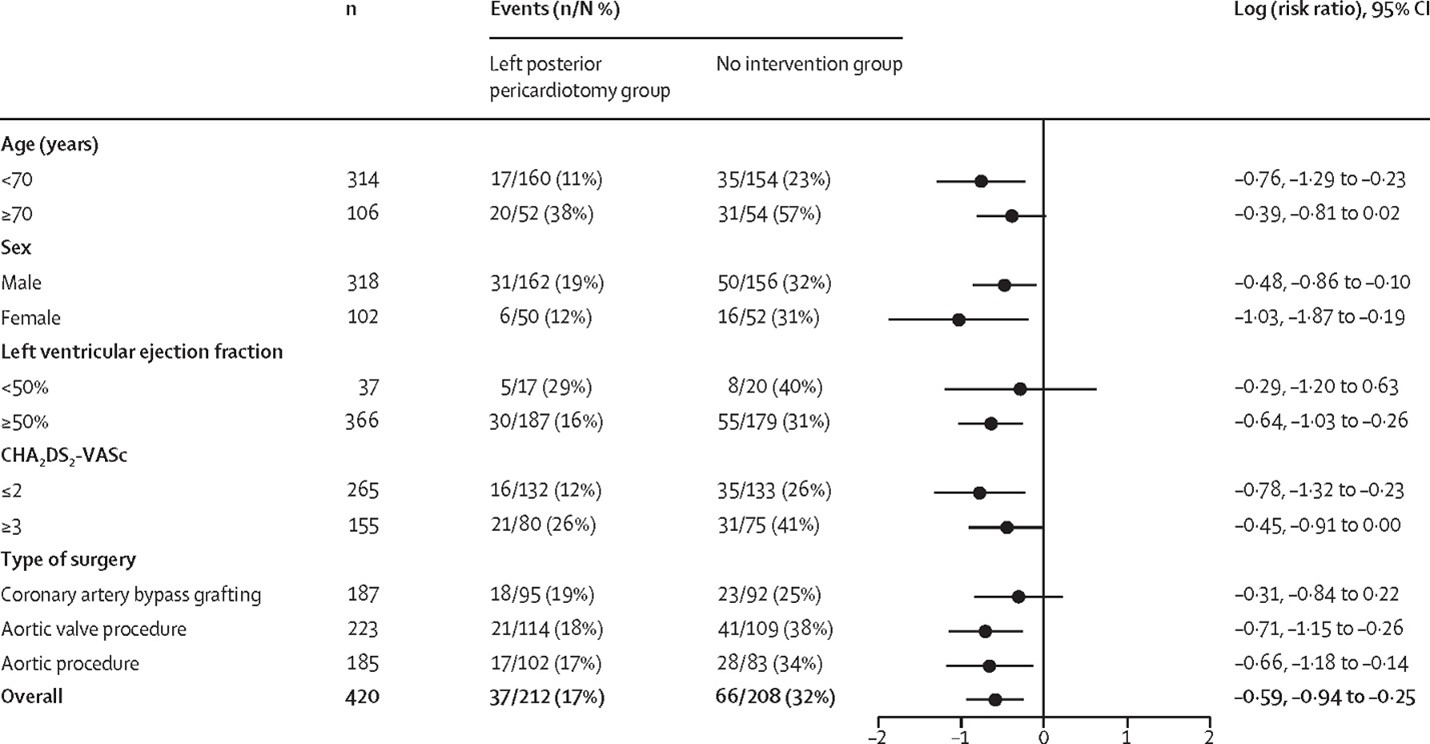

We recently tested the effects of posterior pericardiotomy in a large and rigorous single center trial enrolling 420 patients, stratified by CHA2DS2-VASc score.11 The included subjects underwent elective interventions on the coronary arteries, aortic valve, or ascending aorta, or a combination of these, and were randomly assigned to posterior left pericardiotomy or no intervention. Our results showed that posterior pericardiotomy largely and significantly reduced the incidence of POAF (17% vs. 32%; p<0.001; OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.27-0.70, p<0.001); of note, treatment effect was similar in all the prespecified subgroups (Table 1). The incidence of postoperative pericardial effusion was also lower in the posterior left pericardiotomy group (12% vs. 21%; RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.91), and no posterior left pericardiotomy-related complications were seen.

Our findings support data from previous studies suggesting that efforts to reduce postoperative pericardial effusion could also reduce POAF incidence, as reported in a propensity matched analysis of 697 cardiac surgical patients by Baribeau et al., showing that active tube clearance is associated with lower POAF rates compared to conventional strategies (25% vs. 37%; p=0.01).14

Table 1

Conclusions

Currently adopted interventions aimed at reducing POAF incidence (e.g., antiarrhythmic drugs, colchicine, steroids, magnesium, statin administration, and overdrive atrial pacing),4,15 are only partially effective, and POAF still remains the most common complication following cardiac surgery. A growing amount of evidence suggests that strategies that minimize retained blood in the pericardial space are associated with a significant reduction of POAF incidence. Further studies are warranted to test large-scale interventions to reduce POAF incidence.

Figure 3

References

- Lubitz SA, Yin X, Rienstra M, et al. Long-term outcomes of secondary atrial fibrillation in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2015;131:1648–55.

- LaPar DJ, Speir AM, Crosby IK, et al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation significantly increases mortality, hospital readmission, and hospital costs. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:527–33; discussion 533.

- Gillinov AM, Bagiella E, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Rate control versus rhythm control for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1911–21.

- St-Onge S, Perrault LP, Demers P, et al. Pericardial blood as a trigger for postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;105:321–28.

- Eikelboom R, Sanjanwala R, Le M-L, Yamashita MH, Arora RC. Postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2021;111:544–54.

- Borkon AM, Schaff HV, Gardner TJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of postoperative pericardial effusions and late cardiac tamponade following open-heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 1981;31:512–19.

- Angelini GD, Penny WJ, el-Ghamary F, et al. The incidence and significance of early pericardial effusion after open heart surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1987;1:165–68.

- Reifart N, Blumschein A, Sarai K, Bussmann WD, Satter P. [Pericardial effusions after heart surgery. Incidence and clinical sequelae]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1985;110:1191–94.

- Ikäheimo MJ, Huikuri HV, Airaksinen KE, et al. Pericardial effusion after cardiac surgery: incidence, relation to the type of surgery, antithrombotic therapy, and early coronary bypass graft patency. Am Heart J 1988;116:97–102.

- Gozdek M, Pawliszak W, Hagner W, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials assessing safety and efficacy of posterior pericardial drainage in patients undergoing heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;153:865-75.e12.

- Gaudino M, Sanna T, Ballman KV, et al. Posterior left pericardiotomy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: an adaptive, single-centre, single-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2021;398:2075–83.

- Mulay A, Kirk AJ, Angelini GD, Wisheart JD, Hutter JA. Posterior pericardiotomy reduces the incidence of supra-ventricular arrhythmias following coronary artery bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1995;9:150–52.

- Lau C, Soletti G Jr, Olaria RP, Myers P, Girardi LN, Gaudino M. Posterior left pericardiotomy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg 2021;Dec 9:[Epub ahead of print].

- Baribeau Y, Westbrook B, Baribeau Y, Maltais S, Boyle EM, Perrault LP. Active clearance of chest tubes is associated with reduced postoperative complications and costs after cardiac surgery: a propensity matched analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg 2019;14:192.

- Rezaei Y, Peighambari MM, Naghshbandi S, et al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery: from pathogenesis to potential therapies. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2020;20:19–49.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Dyslipidemia, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Pericardial Disease, Prevention, EP Basic Science, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Aortic Surgery, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Nonstatins, Novel Agents, Statins, Acute Heart Failure, Interventions and Imaging, Echocardiography/Ultrasound, Stress

Keywords: Reactive Oxygen Species, Anti-Arrhythmia Agents, Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors, Magnesium, Methemoglobin, Pericardiectomy, Pericardial Effusion, Atrial Fibrillation, Prospective Studies, Single-Blind Method, Aortic Valve, Cardiopulmonary Bypass, Coronary Vessels, Hemolysis, Lipid Peroxidation, Neutrophil Infiltration, Neutrophils, Pericardial Fluid, Phrenic Nerve, Pulmonary Veins, Respiratory Burst, Coronary Artery Bypass, Echocardiography, Postoperative Period, Hospitalization, Aorta, Oxidative Stress, Heart Failure, Inflammation, Colchicine, Adipose Tissue, Steroids, Stroke

< Back to Listings