"Just What the Doctor Ordered" in 2022: Nicotine Replacement Therapy

Quick Takes

- Tobacco smokers have an estimated life expectancy of 10 years less than the general population.

- A combination of nicotine replacement therapy and bupropion or varenicline is first line in the pharmacologic approach. Combining the three is still an active area of research.

- Ask, Assess, and Advise. Counseling is important and saves lives. Clinicians should revisit the topic of smoking in every encounter.

For years, tobacco companies have promoted a richer, more glamorous lifestyle through cigarette smoking. Our history with tobacco went from "More Doctors Smoke Camels" in the 1940s, the Marlboro Man in the 1960s, to using kid-friendly characters like Joe Camel in the 1990s; our battle against tobacco smoking is still far from a victory. Around 14% (34 million) of the United States (US) population currently smoke cigarettes, with an estimated life expectancy 10 years less than the general population.1

Most smoking deaths are attributed to cancer, cardiovascular disease, or pulmonary disease.2 The detrimental effect of smoking is primarily due to toxins and chemicals produced by the burning of tobacco.2 Disproportionally high rates of smoking occur among under-represented minorities and adults with lower incomes, lower education, or psychiatric conditions.1

It is never too late to quit smoking. Tobacco abstinence translates into a better quality of life and reduces the risk of tobacco-related disease and premature death regardless of age. Our commentary focuses on practical strategies for smoking cessation and preventing relapse.

The pathophysiology of nicotine addiction involves three mechanisms: 1) the rewarding experience of smoking through nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) agonism (which causes dopamine release); 2) the increased tolerance and dependence on nicotine (leading to withdrawal symptoms when nicotine blood levels fall); and 3) the learned behavior of responding to situational and emotional triggers with smoking. Based on these hypothesized mechanisms, therapeutic approaches focus on pharmacologic strategies that relieve withdrawal symptoms and behavioral interventions through counseling and motivational interviews.

Available pharmacologic agents can be broadly bucketed to three major groups: nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), varenicline or bupropion. NRTs come in various forms with different pharmacokinetics that can be exploited to maintain sufficient levels of nicotine throughout the day, thereby minimizing cravings. While nicotine patches provide a slow-onset but longer coverage of basal nicotine levels (~24 hours), oral agents can be used for "fast-on" (10-30 minutes) and "fast-off" (~2 hours) effect.

Combination NRT (such as the patch plus the gum or lozenges) is more effective compared to single NRT products.2,3 Varenicline and bupropion are each more effective than placebo. While varenicline provides withdrawal relief through partial nAChR agonism, bupropion also reduces craving symptoms by preventing the reuptake of dopamine from stimulated mAChR.

A recent double-blind study (EAGLES) comparing the nicotine patch, varenicline, bupropion, and placebo, demonstrated that varenicline was superior to bupropion and the nicotine patch, with no increase in the risk of neuropsychiatric effects. This study led the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to remove the black box warning for varenicline.

Current expert opinion holds that combination NRT (which was not studied in the EAGLES trial) is likely comparable to varenicline in terms of efficacy. Combinations of different pharmacological agents remain an active area of investigation with variable evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of combining varenicline with NRT or bupropion. Thus, a potential first line therapy may include combination NRT or varenicline, with a contingency to consider combination therapy.4–6

To maximize success, treatment should include both pharmacologic therapy and behavioral therapy, the combination of which has been associated with high cessation rates at 6 months.7 Counselors can not only intervene against the psychological etiologies underpinning the habit of smoking using cognitive behavioral therapy, but they also promote medication adherence.

Effective behavioral modalities may include counselor-mediated phone calls, tele-visits, and perhaps implementation of mobile health devices. A recent randomized trial of an automated mobile health intervention (via smart reminder texts to exercise) increased physical activity, suggesting that a similar reminder to adhere to cessation therapy may further assist with maintaining abstinence.8

The role of the clinician is to ask and advise all patients regarding tobacco use. Integrating tobacco counseling into routine clinical practice may be challenging given time constraints. The paradigm, however, needs to shift, and tobacco treatment should be discussed in all medical encounters.

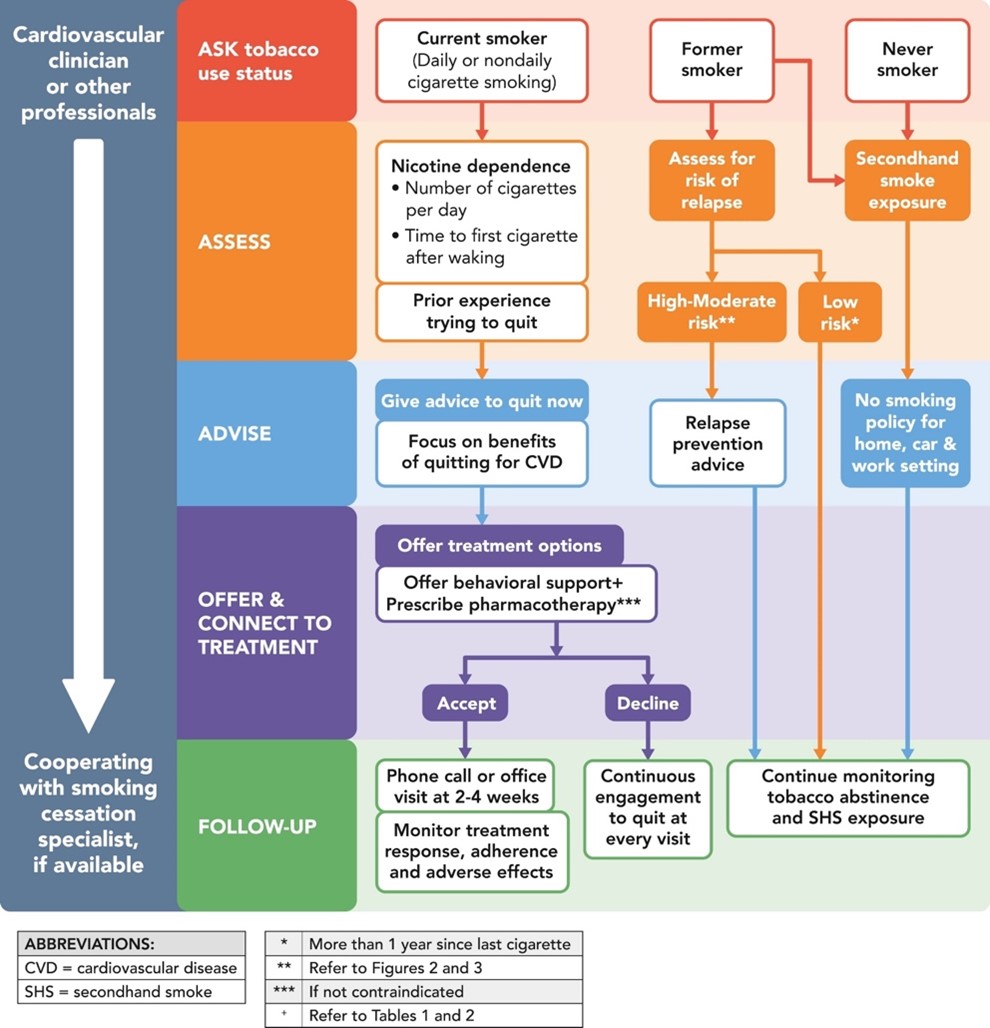

Multiple frameworks have been proposed. One simplistic three-step model is shown in Figure 1, which consists of Ask, Advise and Assist. In the Ask step, a member of the team will assess and clearly document tobacco use at each encounter. The Advise step will deliver clear advice regarding abstinence, highlighting the risks of smoking and the benefits gained from quitting. The Assist step will allow the healthcare team to connect the patient with appropriate resources, future directions, and assistance.9

Figure 1: A Three-Step Model For Smoking Cessation

Smoking, better referred to as tobacco use disorder, should be approached by the clinician as a chronic relapsing-remitting disorder, just like diabetes or hypertension. Adding this diagnosis to the problem list in the electronic health record raises awareness for the patient and all members of the patient's health care team. A strong patient-physician relationship is the pillar for successful smoking cessation, and clinicians should utilize all available resources and start treatment even if their patients are still in the pre-contemplative phase.

Patients should also be proactive in utilizing all available methods. The urge for a smoke is transient, but the effects are long-lasting. Patients will benefit from lifestyle modifications, particularly exercise, mindfulness, and limiting the social cues associated with smoking. If needed, tobacco users at all times can talk to a live counselor at the 1-800-QUIT-NOW line or they can utilize live chat rooms on QuitNet.org. For extra support and fellowship, patients can also attend Nicotine Anonymous meetings.

Nicotine is a highly addictive substance, and it is not easy to quit. Clinicians are obliged to counsel their patients and treat tobacco use as a chronic disease, while patients need to be supported with plans and strategies to help them quit.

Give counseling and provide plenty of it; it saves lives!

References

- Cornelius ME, Wang TW, Jamal A, Loretan CG, Neff LJ. Tobacco product use among adults - United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1736-42.

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2014. PMID: 24455788.

- Lindson N, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Fanshawe TR, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J. Different doses, durations and modes of delivery of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;4:CD013308.

- Thomas KH, Dalili MN, López-López JA, et al. Comparative clinical effectiveness and safety of tobacco cessation pharmacotherapies and electronic cigarettes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addiction 2022;117:861-76.

- Koegelenberg CFN, Noor F, Bateman ED, et al. Efficacy of varenicline combined with nicotine replacement therapy vs varenicline alone for smoking cessation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:155-61.

- Ebbert JO, Hatsukami DK, Croghan IT, et al. Combination varenicline and bupropion SR for tobacco-dependence treatment in cigarette smokers: a randomized trial. JAMA 2014;311:155-63.

- Hartmann-Boyce J, Hong B, Livingstone-Banks J, Wheat H, Fanshawe TR. Additional behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;6:CD009670.

- Martin SS, Feldman DI, Blumenthal RS, et al. mActive: a randomized clinical trial of an automated mHealth intervention for physical activity promotion. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4:e002239.

- Rigotti NA, Kruse GR, Livingstone-Banks J, Hartmann-Boyce J. Treatment of tobacco smoking. JAMA 2022;327:566-77.

- Barua RS, Rigotti NA, Benowitz NL, et al. 2018 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on tobacco cessation treatment: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:3332-65.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiovascular Care Team, Dyslipidemia, Prevention, Lipid Metabolism, Hypertension, Smoking

Keywords: Smoking Cessation, Tobacco Use Cessation Devices, Varenicline, Bupropion, Nicotine, Tobacco Use Disorder, Smoking, Cigarette Smoking, Counselors, Craving, Dopamine, Quality of Life, Double-Blind Method, Tobacco, Tobacco Use, Tobacco Use Cessation, Cardiovascular Diseases, Drug Labeling, Electronic Health Records, Expert Testimony, Mortality, Premature, United States Food and Drug Administration, Substance Withdrawal Syndrome, Receptors, Nicotinic, Medication Adherence, Patient Care Team, Lung Diseases, Chronic Disease, Life Expectancy, Hypertension, Life Style, Diabetes Mellitus, Habits

< Back to Listings