Poll Results: Another Role For Calcium Score?

The poll question revolves around the clinical scenario of a 73-year-old male who presents for a routine follow up with his cardiologist, reports no symptoms, and wishes to discuss discontinuation of some medications. Please see complete details of the clinical vignette here.

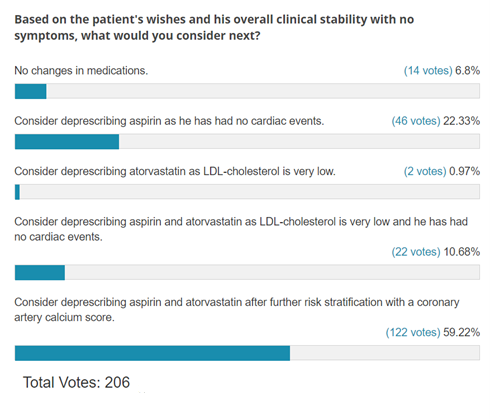

The results of this ACC.org poll revealed that the majority (59%) of voters chose to consider using a coronary artery calcium score to help guide statin and aspirin therapy (correct answer), followed by deprescribing aspirin (22%) in the absence of a cardiac event.

After careful consideration, the patient underwent coronary artery calcium (CAC) testing and was found to have a score of zero. Aspirin and atorvastatin were subsequently discontinued.

The 2018 Multi-society Blood Cholesterol1 and 2019 AHA/ACC Prevention guidelines2 recommend calculating an atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk score to help guide lipid lowering therapy. Among intermediate risk patients (7.5% to 20%), if the decision to start statin pharmacotherapy remains uncertain after the clinical-patient discussion, CAC can be used to further risk stratify patients. Among patients with a CAC score of zero, it is reasonable to defer statin therapy, except for those with a family history of ASCVD, active smokers, or patients with diabetes mellitus. While trials have shown higher bleeding risks with aspirin use for primary prevention, a recent observational study showed asymptomatic patients aged <70 with a low bleeding risk and CAC ≥100 and particularly with CAC ≥400 could derive benefit from aspirin use.3

Available guidance on statin initiation in older patients is less clear, considering that 87.5% of men and 53.6% of women between the ages 60 and 75 years old, without established ASCVD, would potentially qualify for statin treatment on the basis of a 10-year ASCVD risk of >7.5% simply by virtue of their age.4 The value of CAC extends to the older population, such that once the CAC score is known, chronological age simply becomes a number.5 For example, in a cohort of 44,052 asymptomatic patients (mean age 54 ± 10.7 years, 46% women) referred for CAC testing, patients <45 years old with CAC >400 had a 10-fold increased mortality rate, compared to adults ≥75 with CAC=0.5 Notably, 5.6-year survival rates were similar when comparing individuals ≥75 years old with other age groups when CAC=0 (98% vs. 99%, respectively). Similarly, in a pooled population-based analysis (mean age 70.1, 54% women) the cumulative probability of remaining ASCVD-free at 12 years follow up was >90% when CAC=0.6 Other authors have found survival rates >95% among men and women >80 years of age with CAC=0.7

While not explicitly stated in available guidelines, given the favorable prognosis and improved risk discrimination offered by CAC compared to chronological age, it may be reasonable to strategically de-escalate prevention efforts in older adults with no evidence of detectable subclinical atherosclerosis. Deprescribing in older adults with concomitant geriatric conditions such as polypharmacy, frailty, and cognitive dysfunction also offers an opportunity to improve medication safety by reducing adverse drug reactions and focusing on patient-centered outcomes.8

References

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/ APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:3168–3209.

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:e177–e232.

- Cainzos-Achirica M, Miedema MD, McEvoy JW, et al. Coronary artery calcium for personalized allocation of aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in 2019: the MESA study (multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis). Circulation 2020;141:1541-53.

- Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D'Agostino RB, et al. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1422-31.

- Tota-Maharaj R, Blaha MJ, McEvoy JW, et al. Coronary artery calcium for the prediction of mortality in young adults <45 years old and elderly adults >75 years old. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2955-62.

- Yano Y, O'Donnell CJ, Kuller L, et al. Association of coronary artery calcium score vs age with cardiovascular risk in older adults: an analysis of pooled population-based studies. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:986-94.

- Raggi P, Gongora MC, Gopal A, Callister TQ, Budoff M, Shaw LJ. Coronary artery calcium to predict all-cause mortality in elderly men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:17-23.

- Krishnaswami A, Steinman MA, Goyal P, et al. Deprescribing in older adults with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:2584-95.

Clinical Topics: Dyslipidemia, Geriatric Cardiology, Prevention, Lipid Metabolism, Nonstatins, Novel Agents, Statins

Keywords: Aged, Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors, Calcium, Atorvastatin, Cardiovascular Diseases, Follow-Up Studies, Deprescriptions, Polypharmacy, Survival Rate, Primary Prevention, Risk Factors, Atherosclerosis, Aspirin, Prognosis, Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions, Cognitive Dysfunction, Diabetes Mellitus, Patient-Centered Care, Geriatrics

< Back to Listings