Radiation-Induced Carotid Artery Stenosis and Afferent Baroreflex Failure

Quick Takes

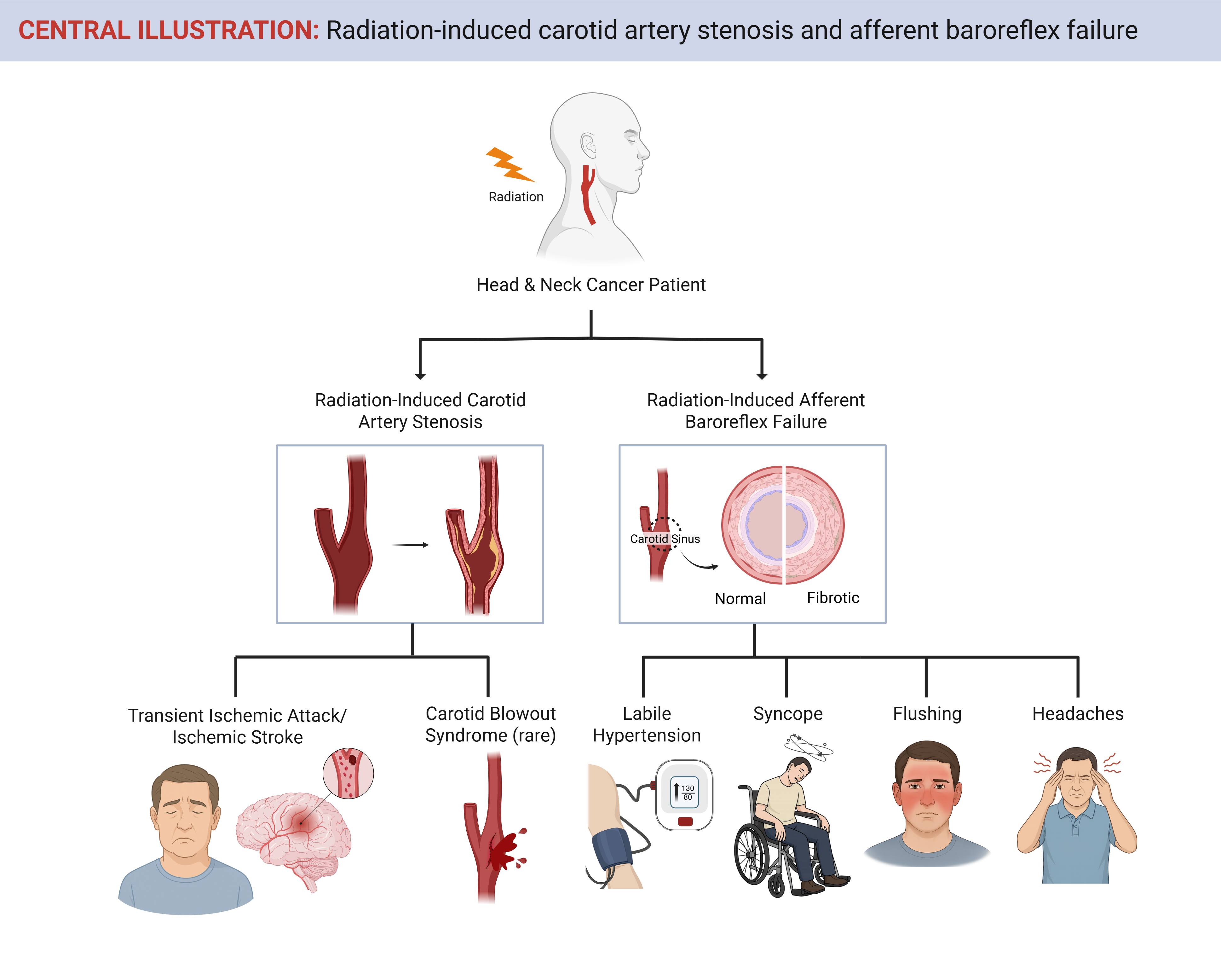

- Radiation therapy improves survival in head and neck cancer, but also carries long-term cardiovascular risks—most notably, carotid artery stenosis and afferent baroreflex failure.

- Up to one in five survivors of head and neck cancer develop radiation-induced carotid artery stenosis within 3 years, increasing their risk of stroke and transient ischemic attack.

- Radiation-induced afferent baroreflex failure causes severe blood pressure instability and recurrent syncope yet remains underrecognized and frequently undiagnosed.

Radiation therapy (RT) is a cornerstone in the treatment of head and neck cancer (HNC), used in up to 75% of patients.1 Because most patients require irradiation of the cervical lymph nodes adjacent to the carotid arteries, sparing these vessels from the radiation field is often not feasible. Although RT has significantly improved cancer control and survival, it is associated with long-term cardiovascular (CV) complications—most notably, radiation-induced carotid artery stenosis (RICAS) and, less commonly recognized but equally serious, radiation-induced afferent baroreflex failure (RABF). Both conditions contribute to substantial morbidity and mortality among survivors of HNC, underscoring the importance of early recognition, prevention, and tailored treatment.

Radiation-Induced Carotid Artery Stenosis

Ionizing radiation causes vascular injury through a cascade of endothelial cell death, inflammation, intimal hyperplasia, medial necrosis, and adventitial fibrosis, ultimately initiating or accelerating atherosclerosis.2 These changes are dose dependent and can affect the entire irradiated carotid artery segment—not just the bifurcation.3 Importantly, RICAS is often asymptomatic until high-grade stenosis develops, typically years after RT exposure.

Symptomatic RICAS may present with transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), ischemic stroke, or, rarely, carotid blowout syndrome. Early subclinical manifestations include increased carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), detectable by vascular ultrasonography.4 The incidence of ≥50% carotid artery stenosis has been reported in 21% of patients within 3 years post RT, with TIA or stroke occurring in approximately 5% by 5 years and 10% by 10 years.3,5 However, it remains unclear whether these rates have changed over time in response to increased recognition and advancements in RT. Surveillance practices vary widely across institutions,1,6-8 and the absence of long-term studies evaluating modern RT techniques limits clinicians' abilities to determine whether changes in modality have meaningfully influenced these outcomes.

Duplex ultrasonography is the primary modality for monitoring CIMT and detecting carotid artery stenosis, whereas CT and magnetic resonance angiography are typically reserved for further evaluation or preintervention planning. Risk factors for RICAS include older age, higher cumulative RT dose, traditional CV risk factors such as hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), smoking, and prior vascular disease.3,5

Optimal screening or surveillance intervals for asymptomatic patients with prior neck irradiation is unclear, and most major guidelines have no explicit recommendations that stratify patients by RT dose. Some professional societies advise against RICAS screening due to insufficient evidence that early detection and intervention alter clinical outcomes,1,6 whereas others support risk-based screening.3,7,8 The American Head & Neck Society (AHNS) recommends considering a carotid ultrasonogram every 2-5 years after RT,7 whereas the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS) and other experts recommend, in the context of rigorous baseline vascular assessment for head and neck patients, screening of individuals at high risk as early as 1 year post RT, with follow-up every 3-5 years.3,8

Management of RICAS generally follows guidelines for atherosclerotic carotid artery disease, with certain caveats. Medical therapy typically includes antiplatelet agents, statins, and aggressive control of modifiable CV risk factors. However, data specific to RICAS are sparse, and no pharmacologic intervention has been validated specifically for this condition. For patients with asymptomatic high-grade (>70%) stenosis or symptomatic moderate-to-severe (>50%) stenosis, revascularization is indicated. Carotid artery stenting is favored over endarterectomy due to RT-induced fibrosis and altered neck anatomy, which increases surgical complexity and risk.6

Preventive strategies focus on minimizing radiation exposure to the carotid arteries. Advances in RT, such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy and proton therapy, have enabled more precise targeting of tumor tissues while reducing collateral damage. However, recent data suggest that even low RT doses (as low as 10 Gy) may confer risk, indicating that a truly safe threshold for carotid artery exposure may not be practicable. These data highlight the pressing need for adjunctive preventive interventions beyond dose modification.3 Optimizing CV health through lifestyle changes and medical therapy remains essential. Control of HTN, dyslipidemia, and DM, and cessation of smoking, are universally recommended. Yet, evidence supporting a targeted preventive pharmacologic strategy for RICAS is lacking, and further research is needed in this space.8

Radiation-Induced Afferent Baroreflex Failure

The afferent limb of the baroreflex arc consists of mechanosensitive nerve endings—primarily from the glossopharyngeal nerve—embedded in the adventitia of the carotid sinus. Neck irradiation can cause progressive atherosclerosis, fibrosis, and adventitial damage, leading to disruption of these afferent fibers and subsequent baroreflex failure.2,9 RT-induced injury results in both direct neural damage and secondary effects from vascular stiffening and fibrosis, which together impair the ability of the baroreceptors to sense and transmit blood pressure (BP) changes.9 RABF is a late sequela, occurring long-after radiotherapy; its prevalence in survivor populations is undefined because of a lack of rigorous assessment or longitudinal data sets.

Clinically, RABF typically presents years after RT exposure and is irreversible once established.9 It is characterized by labile BP with unpredictable and often extreme fluctuations in both BP and heart rate.9 Symptoms may include paroxysmal HTN, flushing, headaches, and syncope. In severe cases, patients experience debilitating functional impairment, frequent falls, and marked reduction in quality of life (QoL).9

Diagnosis is challenging and relies on clinical history and autonomic testing, including the standardized autonomic reflex screen (ARS), endorsed by major neurology societies.10 Autonomic dysfunction is graded using the composite autonomic severity score (CASS), with cardiovagal and adrenergic subscores assessing parasympathetic and sympathetic components.10 An exaggerated pressor response to cold exposure can help confirm intact efferent pathways, supporting a diagnosis of afferent failure.10 No formal surveillance protocols currently exist to detect early RABF, although evidence suggests subclinical carotid artery baroreceptor injury may precede overt dysfunction.

Because the BP changes in RABF are drastic and unpredictable in nature,9 RABF is among the most challenging BP disorders to manage, with no established evidence-based treatment guidelines to date. Management remains empirical. Nonpharmacologic strategies—such as biofeedback, water boluses, and vascular compression—may provide symptomatic relief in some patients. Pharmacologic interventions, including low-dose central sympatholytics (e.g., methyldopa or guanfacine) for hypertensive episodes and agents such as midodrine or fludrocortisone for hypotension, have been used anecdotally in more severe cases. However, none of these therapies have been validated in prospective clinical trials.9 Heightened awareness, earlier recognition, and dedicated research into both preventive and therapeutic strategies are urgently needed to improve outcomes for affected patients.

Conclusion

As survival rates for patients with HNC continue to improve, clinical focus must expand beyond tumor control to encompass long-term CV and autonomic complications such as RICAS and RABF (Figure 1; Table 1). Increased awareness, timely diagnosis, risk-based screening, and individualized management are essential to improving long-term outcomes and preserving QoL in this growing population of survivors of cancer.

Figure 1: Carotid Artery Stenosis and Afferent Baroreflex Failure as Complications of RT Among Survivors of HNC

Created in BioRender. Shen, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/sngwuk0

HNC = head and neck cancers; RT = radiation therapy.

Table 1: Summary Characteristics of RICAS and RABF

|

Feature

|

RICAS

|

RABF

|

| Pathophysiology | Ionizing radiation causes endothelial injury, inflammation, intimal hyperplasia, medial necrosis, and adventitial fibrosis, leading to accelerated atherosclerosis. | Direct neural damage and adventitial fibrosis impair baroreceptor function; stiffened carotid artery walls reduce mechanosensation. |

| Incidence | ≥50% carotid artery stenosis in ~21% at 3 years post RT; stroke or TIA in 5-10% over 5-10 years | True prevalence unknown; likely underrecognized and underdiagnosed; delayed onset, often years post RT |

| Manifestations | Often asymptomatic until advanced; symptoms include TIA, ischemic stroke, CBS (rare) | Labile HTN, syncope, flushing, headaches; in severe cases, functional decline and falls |

| Diagnosis | DUS for screening and CIMT; CT/MRA for further evaluation | Clinical history + autonomic testing (ARS, CASS, cold pressor response) |

| Surveillance | Controversial; some societies recommend US in pts at high risk every 1-5 years post RT | No formal surveillance protocols; subclinical baroreceptor injury may precede clinical RABF |

| Treatment | Medical therapy (statins, antiplatelets, CV risk-factor control); revascularization with stenting preferred over surgery | Empirical; low-dose central sympatholytics (e.g., methyldopa, guanfacine); no evidence-based guidelines |

| Prevention | Minimize carotid artery radiation exposure with IMRT/proton therapy; optimize CV risk factors; no validated pharmacologic prophylaxis | Preventive strategies not established — research needed. Early detection of autonomic dysfunction may help. |

ARS = autonomic reflex screen; CASS = composite autonomic severity score; CBS = carotid blowout syndrome; CT = computed tomography; DUS = duplex ultrasonogram; HTN = hypertension; IMRT = intensity-modulated radiation therapy; MRA = magnetic resonance angiography; pts = patients; RABF = radiation-induced afferent baroreflex failure; RICAS = radiation-induced carotid artery stenosis; US = ultrasonogram.

References

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Head and Neck Cancers (Version 4.2025) (NCCN website). 2025. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf. Accessed 08/11/2025.

- Venkatesulu BP, Mahadevan LS, Aliru ML, et al. Radiation-induced endothelial vascular injury: a review of possible mechanisms. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2018;3(4):563-572. Published 2018 Aug 28. doi:10.1016/j.jacbts.2018.01.014

- Carpenter DJ, Patel P, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Long-term risk of carotid stenosis and cerebrovascular disease after radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2025;131(1):e35089. doi:10.1002/cncr.35089

- Koutroumpakis E, Mohamed ASR, Chaftari P, et al. Longitudinal changes in the carotid arteries of head and neck cancer patients following radiation therapy: results from a prospective serial imaging biomarker characterization study. Radiother Oncol. 2024;195:110220. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2024.110220

- Texakalidis P, Giannopoulos S, Tsouknidas I, et al. Prevalence of carotid stenosis following radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2020;42(5):1077-1088. doi:10.1002/hed.26102

- AbuRahma AF, Avgerinos ED, Chang RW, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines for management of extracranial cerebrovascular disease. J Vasc Surg. 2022;75(1S):4S-22S. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2021.04.073

- Goyal N, Day A, Epstein J, et al. Head and neck cancer survivorship consensus statement from the American Head and Neck Society. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2021;7(1):70-92. Published 2021 Nov 30. doi:10.1002/lio2.702

- Mitchell JD, Cehic DA, Morgia M, et al. cardiovascular manifestations from therapeutic radiation: a multidisciplinary expert consensus statement from the International Cardio-Oncology Society. JACC CardioOncol. 2021;3(3):360-380. Published 2021 Sep 21. doi:10.1016/j.jaccao.2021.06.003

- Biaggioni I, Shibao CA, Diedrich A, Muldowney JAS 3rd, Laffer CL, Jordan J. Blood pressure management in afferent baroreflex failure: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(23):2939-2947. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.027

- Cheshire WP, Freeman R, Gibbons CH, et al. Electrodiagnostic assessment of the autonomic nervous system: a consensus statement endorsed by the American Autonomic Society, American Academy of Neurology, and the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Clin Neurophysiol. 2021;132(2):666-682. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2020.11.024

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Vascular Medicine, Cardio-Oncology

Keywords: Radiation, Cancer Survivors, Head and Neck Neoplasms, Carotid Stenosis, Baroreflex