Surgical Systemic Vein Turndown For Thoracic Duct Decompression in Fontan Patients With Protein-Losing Enteropathy: Role of Multimodality Imaging

Quick Takes

- Protein-losing enteropathy is a debilitating complication of Fontan circulation, characterized by congestion of the thoracic duct (TD) that normally trains into the innominate vein (InV).

- Two surgical groups have recently reported success with surgical TD decompression by anastomosing the InV to a lower-pressure atrium, known as the innominate vein turndown procedure.

- This expert analysis is intended to serve as a practical guide to using multimodality imaging in preoperative planning and postsurgical surveillance for clinicians considering this novel procedure.

Introduction

Fontan surgery for palliation of single-ventricle (SV) disease involves creation of a total cavopulmonary anastomosis, which results in an obligatory rise in central venous pressure. Because the thoracic duct (TD) drains into the systemic venous circulation, this elevated pressure leads to TD hypertension and lymphatic reflux, often manifesting as protein-losing enteropathy (PLE)—a debilitating complication of Fontan physiology.1 PLE is frequently refractory to medical therapy and may ultimately necessitate orthotopic heart transplant (OHT). However, donor scarcity, high peritransplant risk, and reports of post-transplant recurrence limit the effectiveness of OHT as a definitive solution.2

These challenges have spurred development of an alternative strategy: thoracic duct decompression (TDD) through surgical diversion of the innominate vein (InV; or any other systemic vein that receives the TD) to a lower-pressure atrial chamber, commonly referred to as the turndown procedure.3-5 Although there are some reports of success using a complex transcatheter approach for InV (or systemic vein) turndown at highly specialized lymphatic centers,3 increasing attention is being directed toward a surgically simpler method of TDD. The surgical approach reported by Hraska et al. and more recently by Alaeddine at al. from the authors' center, Phoenix Children's, may offer broader feasibility and potentially wider application for PLE relief.4,5 This expert analysis details key considerations for preoperative planning and postoperative surveillance of the surgical TDD procedure, building on the experiences of these pioneering surgical groups.

Preoperative Planning for the TDD Procedure

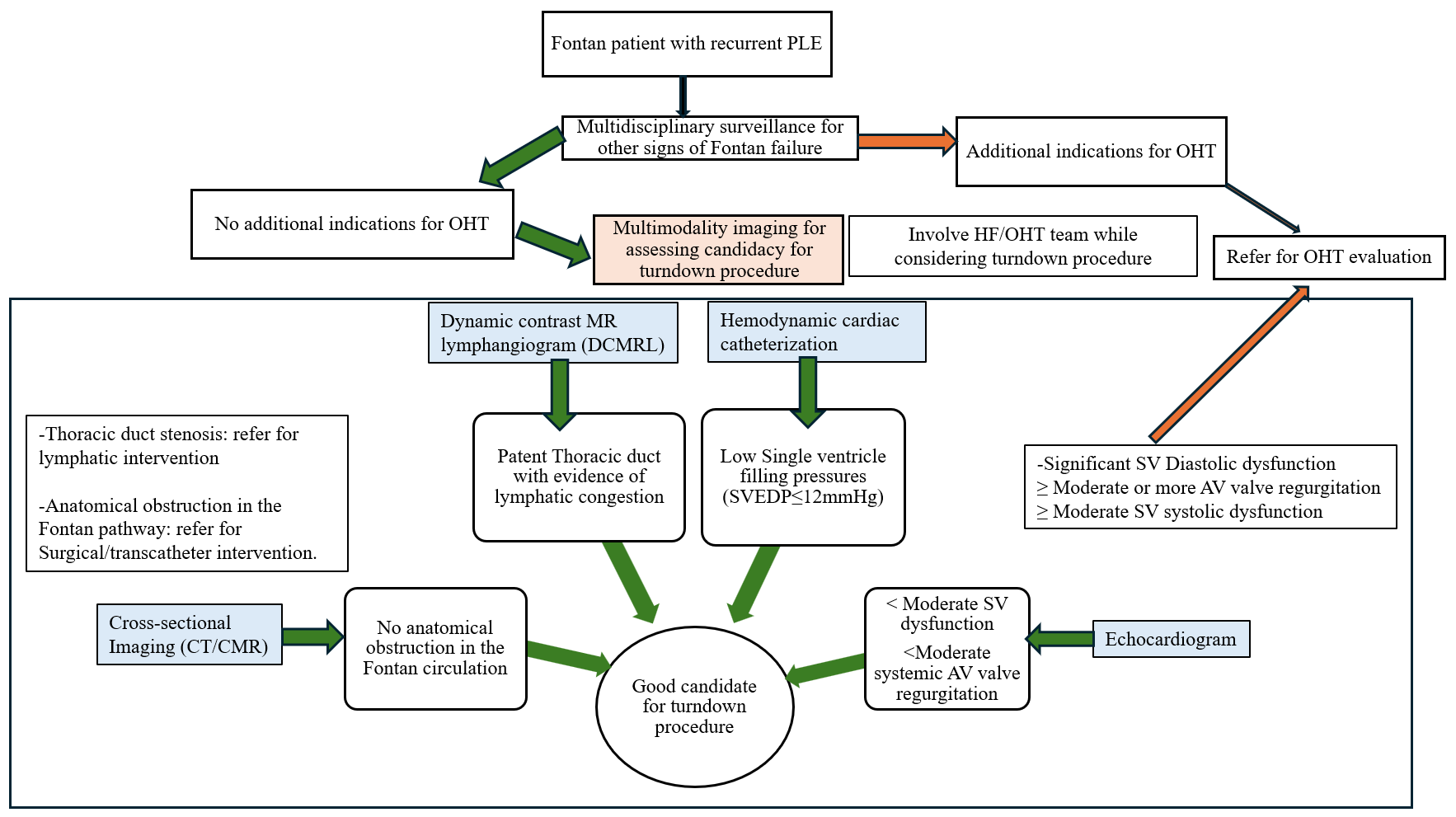

Meticulous preoperative planning with a multidisciplinary approach is paramount to the success of the procedure.4,5 It is important to classify patients as isolated PLE versus those with multicompartment lymphatic abnormalities such as chylothorax because the latter may require additional lymphatic procedures, as described by Dori et al. and Hraska et al.1,5 Figure 1 shows a practical algorithm for patient selection in isolated PLE. As PLE is a marker of failing Fontan physiology, patients who demonstrate additional features of Fontan failure may be referred primarily for OHT in preference to the turndown procedure. Once a patient is deemed eligible for the surgical turndown procedure, subsequent selection relies heavily on multimodality imaging.

Figure 1: Preoperative Planning for TDD Using the Surgical Systemic Vein Turndown Procedure for Relief of PLE in Fontan Patients

AV = atrioventricular; CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; CT = computed tomography; DCMRL = dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography; HF = heart failure; OHT = orthotopic heart transplant; PLE = protein-losing enteropathy; SV = single-ventricle; SVEDP = single-ventricle end-diastolic pressure; TDD = thoracic duct decompression.

Preoperative Lymphatic Evaluation

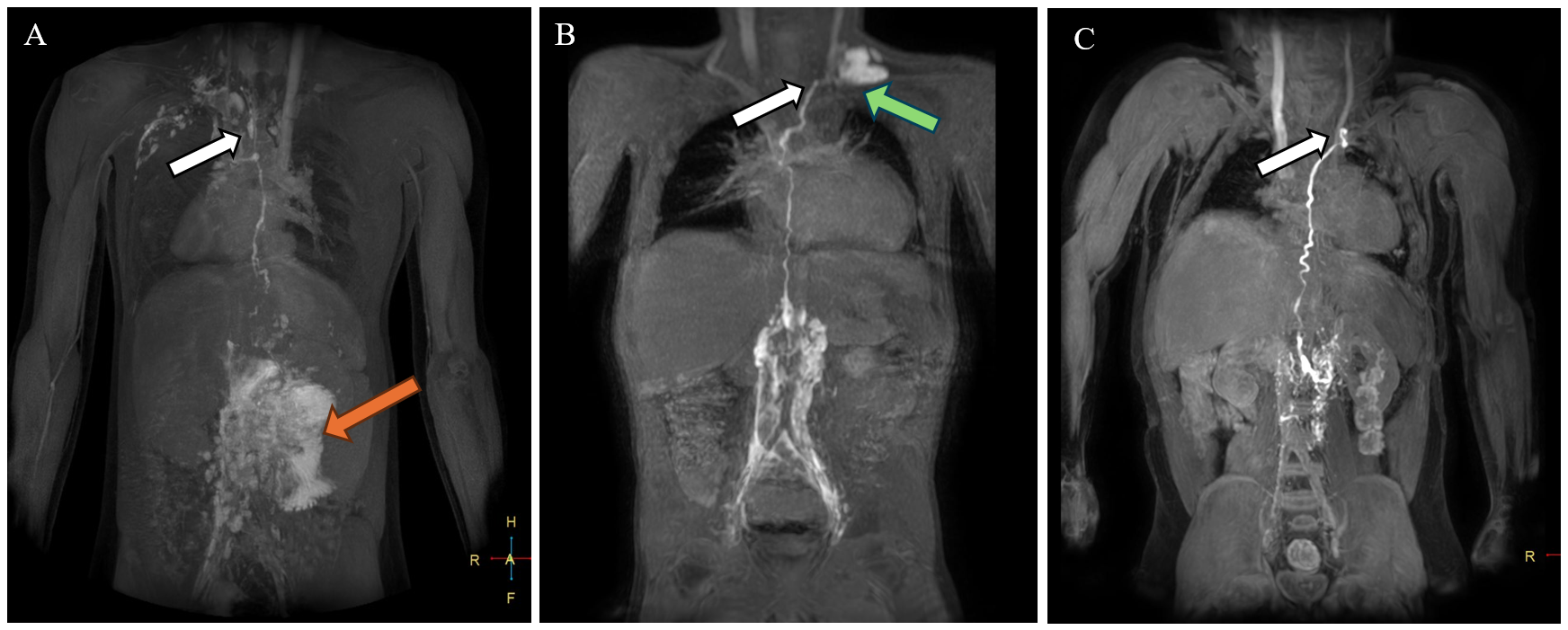

Dori et al. described multiple patterns of lymphatic abnormalities in SV patients using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography (MRL).1 It is vital to establish patency and location of the TD. The site of TD drainage may vary in complex anatomical types. In the five Fontan patients described by Alaeddine et al., TD terminated consistently at the jugulo-subclavian venous confluence, although the side of drainage (right vs. left) varied depending on the venous anatomy.4 Figure 2 shows representative images from three Fontan patients who underwent successful surgical turndown at the authors' center.

Figure 2: Results of Preoperative DCMRL for Surgical Planning in Three Fontan Patients With Recurrent PLE

(Panel A) DCMRL on a Fontan patient with heterotaxy syndrome. T1 post–contrast volume MIP acquired 19 min after bilateral inguinal lymph node contrast injection demonstrated marked lymphatic reflux into the mesentery (orange arrow) and an intact TD terminating at the right venous angle (white arrow). (Panel B) T1 postcontrast thick slab MIP acquired 12 min after bilateral inguinal lymph node contrast injection demonstrated lymphangiectasia along the lumbar spine, an intact TD terminating at the left venous angle (white arrow), and lymphatic reflux into the right supraclavicular region (green arrow). (Panel C) T1 postcontrast thick slab MIP acquired 5 min after bilateral inguinal lymph node contrast injection demonstrated an intact normal-appearing TD terminating at the left venous angle (white arrow) without significant lymphangiectasia or lymphatic reflux.

DCMRL = dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography; MIP = maximum-intensity projection; PLE = protein-losing enteropathy; TD = thoracic duct.

Preoperative Use of Cross-Sectional Imaging (Computed Tomography/Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

Cross-sectional imaging is especially useful in patients with complex anatomical subtypes (e.g., dextrocardia, bilateral superior vena cava [SVC], atrial juxtaposition) to assist in surgical planning. Three-dimensional modalities facilitate delineation of the optimal surgical route and may identify stenosis or obstruction within these channels that can be addressed to partially relieve the PLE symptoms.

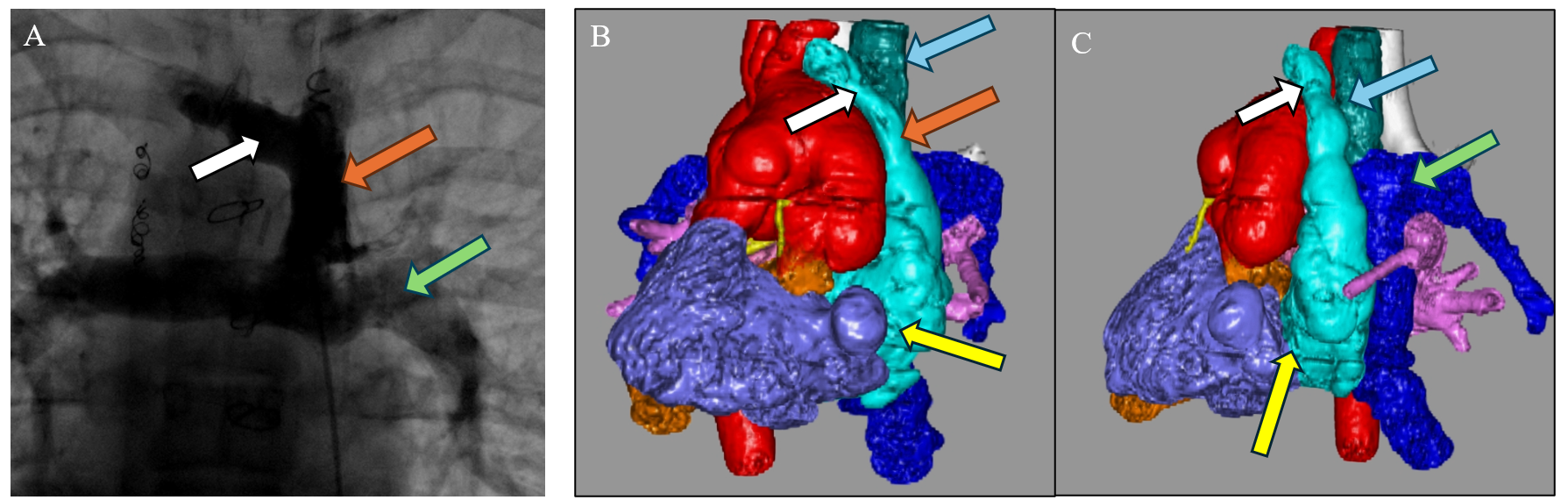

Figure 3 illustrates the utility of multimodality imaging in a 16-year-old girl with a complex heterotaxy syndrome and PLE from the case series by Alaeddine et al.4 MRL revealed TD drainage into the right internal jugular vein (IJV), which in turn connected to the left SVC—an unusual anatomical variant necessitating modification of the surgical approach. Postoperative computed tomography (CT) angiography demonstrated the surgical reconstruction used based on this information (Figure 3, panel B). The surgery involved transection of the left IJV from the left SVC with oversewing of the distal stump, detachment of the left SVC from the left pulmonary artery (LPA), and reconstruction of the superior cavopulmonary anastomosis (Glenn anastomosis) using a 14 mm Gore-Tex (W. L. Gore & Associates) interposition graft between the left IJV and the LPA. The left SVC was anastomosed to the left atrial appendage, with enlargement of the anterior-left anastomotic aspect using a bovine pericardial patch.4

Figure 3: Pre- and Postoperative CT Angiograms in a Complex Case

Preoperative angiogram (panel A) and postoperative CT angiograms (panels B, C) in a complex case of a patient with heterotaxy syndrome, dextrocardia, left-sided SVC, TD draining into the right-sided IVJ, and recurrent PLE. The surgical technique for turndown was modified on the basis of the patient's systemic venous anatomy. (Panel A) Preoperative CC. AP projection of an angiogram showing a left-sided SVC (orange arrow) with cavopulmonary anastomoses (Glenn anastomoses). The white arrow indicates the right InV and the green arrow indicates the LPA. (Panels B, C) The AP view (panel B) and left-sided view (panel C) on postoperative CT angiograms of the same patient with 3D reconstruction after an InV turndown procedure. The right InV (white arrows) and left SVC (orange arrow in panel B) are seen draining into the left-sided atrial appendage (yellow arrows). An interposition graft (blue arrows) was used to reconstruct the Glenn anastomosis by connecting the left IJV to the LPA (green arrow in panel C).

3D = three-dimensional; AP = anteroposterior; CC = cardiac catheterization; CT = computed tomography; InV = innominate vein; IVJ = internal jugular vein; LPA = left pulmonary artery; PLE = protein-losing enteropathy; SVC = superior vena cava; TD = thoracic duct.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging can be particularly helpful in SV size and function assessment and can help quantify the severity of the atrioventricular valve (AVV) regurgitant fraction. Assessment of aortopulmonary collaterals are particularly helpful because these vessels can contribute to volume overload on the SV and can be addressed during hemodynamic cardiac catheterization.

Preoperative Echocardiography

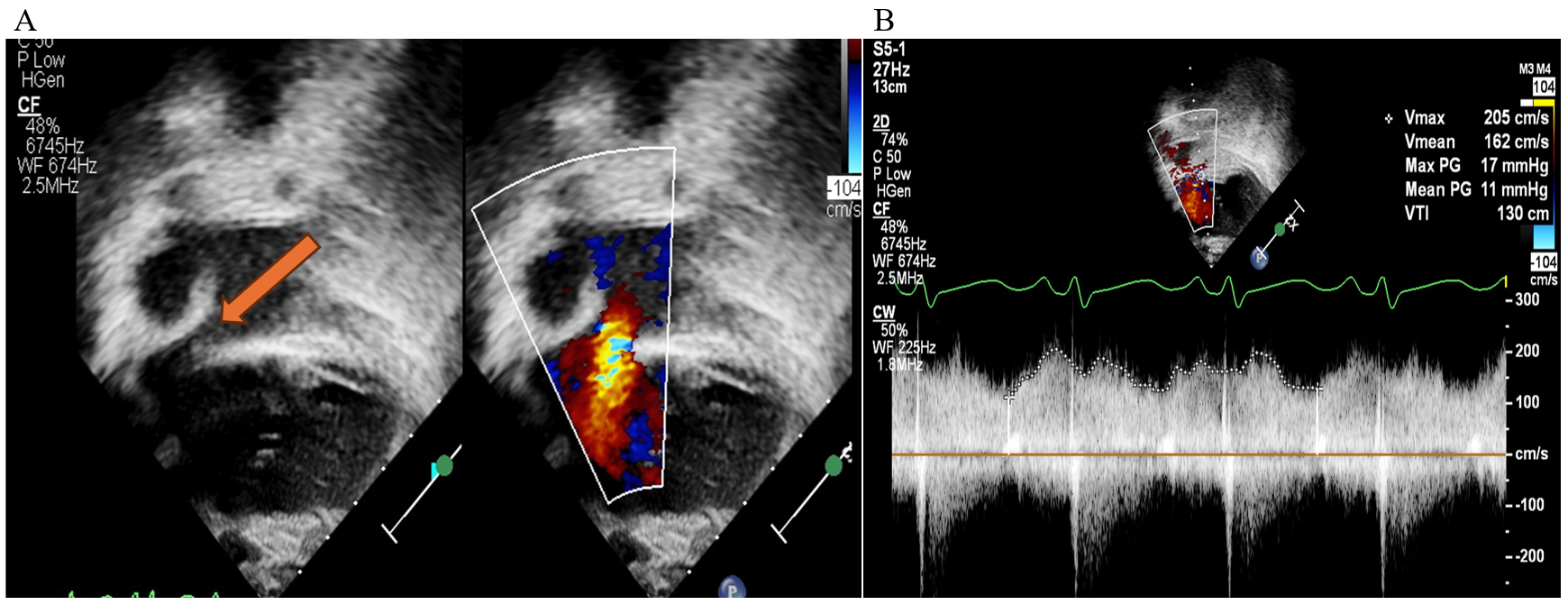

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is essential for evaluating intracardiac anatomy and hemodynamics. In addition, TTE may allow identification of mechanical contributors to PLE, such as a restrictive atrial septum (Figure 4). Significant AVV regurgitation or SV systolic dysfunction may preclude effective surgical TDD, with OHT being the more appropriate strategy.

Figure 4: TTE Images of a Fontan Patient With Early-Onset PLE After a Fontan Procedure

(Panel A) 2D and color flow interrogation of the atrial septum in a 5-year-old Fontan patient (tricuspid atresia with l-TGA) who developed PLE within a few months after an extracardiac Fontan surgery. The orange arrow points to narrowing of the ASD. Color flow Doppler suggests accelerated flow with restriction of the atrial septum. (Panel B) Spectral Doppler across the ASD in the same patient confirms restriction of the atrial septum showing elevated MG 11 mm Hg across the ASD, later confirmed by CC. He subsequently underwent surgical revision of his Fontan pathway.

2D = two-dimensional; ASD = atrial septal defect; CC = cardiac catheterization; l-TGA = levo-transposition of the great arteries; MG = mean gradient; PLE = protein-losing enteropathy; TTE = transthoracic echocardiographic.

Preoperative Hemodynamic Cardiac Catheterization

Direct measurement of Glenn and Fontan pathway pressures enables optimization of medical therapy. The rationale for TDD is that redirecting lymphatic flow into a lower-pressure atrium may alleviate PLE. Therefore, patients with SV end-diastolic pressure ≥12 mm Hg may not be favorable candidates for turndown.4

Procedural Considerations

SV anatomy determines the final surgical approach to the turndown procedure.1,4 Several modifications of the surgical techniques have been described by Hraska et al. and Alaeddine et al.4,5

Postoperative Follow-Up: Role of Multimodality Imaging

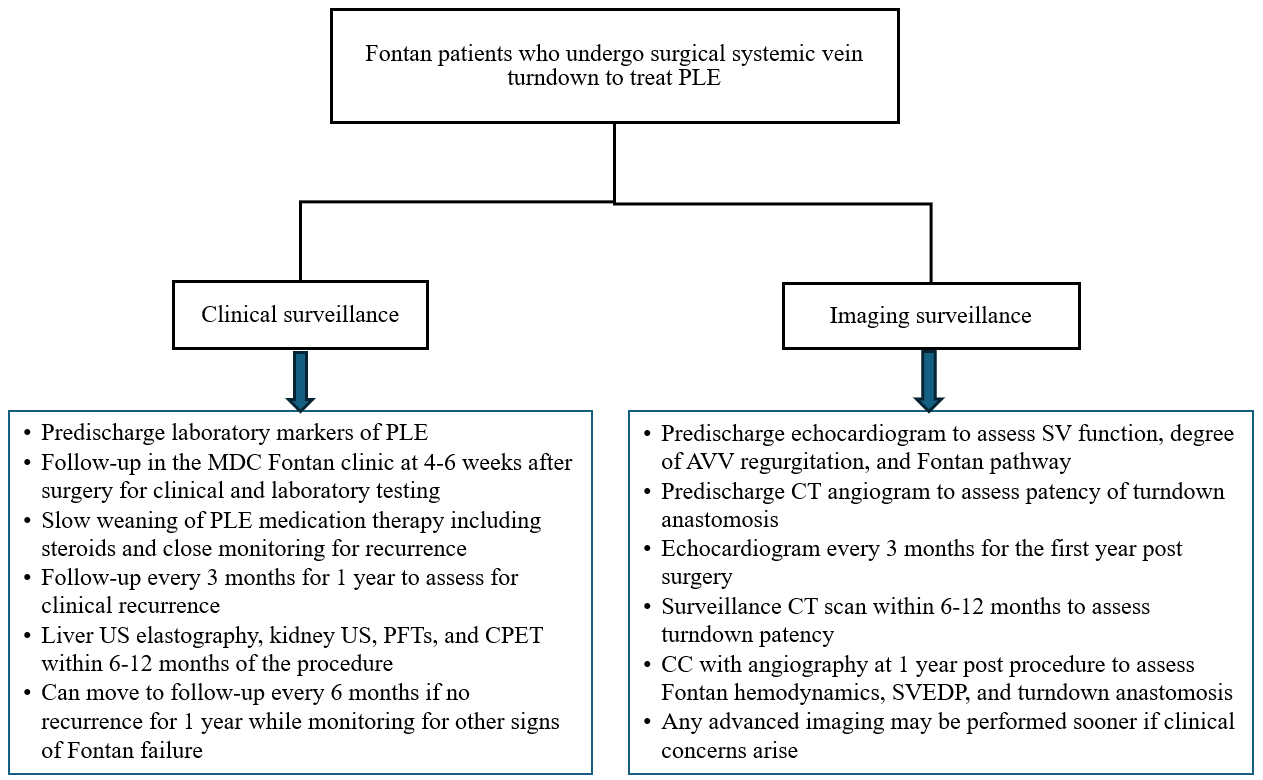

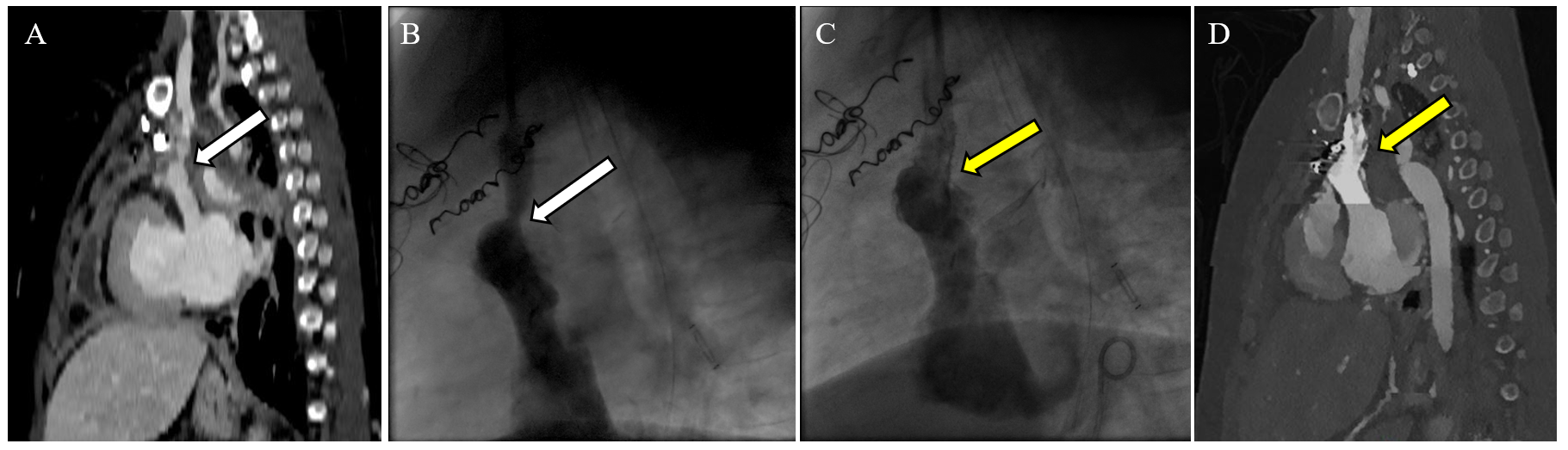

The turndown anastomosis requires close surveillance for thrombus formation or anatomical stenosis. Figure 5 summarizes a multipronged approach to postoperative monitoring. Figure 6 shows how a turndown stenosis was detected on a predischarge CT angiogram, which was successfully treated with stent angioplasty. It is essential that all patients who develop PLE continue to be monitored closely for development or worsening of other Fontan-related sequelae, including liver fibrosis.6

Figure 5: Postoperative Surveillance of Fontan Patients Who Undergo the Surgical Systemic Venous Turndown Procedure to Treat PLE

AVV = atrioventricular valve; CC = cardiac catheterization; CPET = cardiopulmonary exercise test; CT = computed tomography; MDC = multidisciplinary clinic; PFT = pulmonary function test; PLE = protein-losing enteropathy; SV = single-ventricle; SVEDP = single-ventricle end-diastolic pressure; US = ultrasonography.

Figure 6: Postoperative Multimodality Imaging Surveillance of the Turndown Anastomosis in a Fontan Patient

Narrowing at surgical anastomosis was detected by surveillance CT angiogram in a patient (panel A), which was confirmed on CC (panel B) followed by successful stent angioplasty (panel C). (Panel A) CT angiogram (sagittal section) on a 9-year-old Fontan patient before hospital discharge after a surgical InV turndown procedure. The white arrow points to discrete stenosis at the site of the InV to an atrial appendage anastomosis. (Panel B) Lateral projections of a hand injection in the left IJV showing the flow into the InV turndown. The white arrow shows moderate narrowing at the InV to an atrial appendage anastomosis with a 4 mm Hg gradient. (Panel C) Lateral projections of hand injection in the left IJV after stent angioplasty of the InV to the atrial appendage using a 10 x 19 mm PALMAZ GENESIS (Cordis) stent (yellow arrow). There is no residual pressure gradient across the stent at the end of the procedure. (Panel D) CT angiogram (sagittal section) on the same patient 6 months after angioplasty and stent placement showing a patent stent (yellow arrow) and turndown anastomosis.

CC = cardiac catheterization; CT = computed tomography; IJV = internal jugular vein; InV = innominate vein.

Conclusions

The surgical technique of TDD using surgical systemic venous turndown anastomosis is a promising new alternative for relief of PLE that continues to evolve. Surgical enters considering this innovative technique should use multimodality imaging in a systematic manner for pre- and postoperative monitoring and decision-making. A multidisciplinary approach with involvement of an institutional or regional Fontan team may be beneficial for coordinating long-term care for these patients.

References

- Dori Y, Smith CL. Lymphatic disorders in patients with single ventricle heart disease. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:828107. Published 2022 Jun 10. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.828107

- Sagray E, Johnson JN, Schumacher KR, West S, Lowery RE, Simpson K. Protein-losing enteropathy recurrence after pediatric heart transplantation: multicenter case series. Pediatr Transplant. 2022;26(5):e14295. doi:10.1111/petr.14295

- Smith CL, Dori Y, O'Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Gillespie MJ, Rome JJ. Transcatheter thoracic duct decompression for multicompartment lymphatic failure after Fontan palliation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15(7):e011733. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.011733

- Alaeddine M, Bhat DP, Pohlman J, et al. Surgical thoracic duct decompression: the right choice for Fontan-associated protein-losing enteropathy?. JTCVS Tech. 2025;31:133-141. Published 2025 May 3. doi:10.1016/j.xjtc.2025.04.013

- Hraska V, Hjortdal VE, Dori Y, Kreutzer C. Innominate vein turn-down procedure: killing two birds with one stone. JTCVS Tech. 2021;7:253-260. Published 2021 Mar 18. doi:10.1016/j.xjtc.2021.01.045

- Bulut OP, Bailey SS, Bhat DP. Accuracy of elastography versus biopsy in assessing severity of liver fibrosis in young Fontan patients. Cardiol Young. Published online May 28, 2024. doi:10.1017/S1047951124025241

Clinical Topics: Cardiac Surgery, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Cardiac Surgery and CHD and Pediatrics, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Imaging, CHD and Pediatrics and Interventions, Interventions and Imaging, Cardiovascular Care Team

Keywords: Protein-Losing Enteropathies, Fontan Procedure, Multimodal Imaging, Thoracic Duct