The Role of Exercise in Cardio-Oncology

Quick Takes

- Exercise is an important nonpharmacologic strategy to improve cardiovascular health in both patients with and survivors of cancer.

- Dynamic assessments of cardiac function and biomarkers may better capture the cardioprotective effects of exercise than traditional resting measures.

- More research is needed to optimize exercise delivery and support its integration into cancer care.

As cancer survival rates improve due to advances in treatment, new challenges have emerged; one of the most serious is cancer therapy–related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) and subsequent cardiovascular disease (CVD) among survivors of cancer.1 According to recent cancer survivorship data, CVD-related mortality in patients with cancer often exceeds cancer-related mortality beyond 5-7 years of cancer diagnosis, underscoring the urgent need for enhanced cardioprotective strategies.2 This elevated CVD risk is multifactorial, stemming from the accumulation of untreated cardiovascular (CV) risk factors, high-risk lifestyle behaviors, and the direct cardiotoxic effects of cancer therapies. Pharmacologic strategies to mitigate CTRCD are well established for certain therapies, such as anthracyclines, with emerging therapies actively under investigation.1 In parallel, evidence supporting nonpharmacologic interventions, particularly exercise, has grown substantially. Exercise has demonstrated benefits in improving fatigue, quality of life, and physical functioning in patients with cancer. This evidence has resulted in guideline recommendations for oncology providers to prescribe aerobic and resistance exercise during active treatment to mitigate adverse effects of cancer treatments.3

The CV Benefits of Exercise in Patients With Cancer

The role of exercise in addressing CV risk and outcomes in patients with cancer is increasingly recognized. Exercise training has been shown to enhance skeletal muscle metabolic efficiency, leading to improved glycemic control, while also favorably altering body composition by reducing fat mass and increasing lean muscle in patients with cancer.4 Exercise also improves cardiorespiratory fitness, defined as peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak) achieved during cardiopulmonary exercise testing. A recent meta-analysis of four trials demonstrated clinically significant improvements in VO2peak after 8-12 weeks of exercise training among patients with breast cancer exposed to anthracyclines and/or trastuzumab.5 This finding aligns with results from Foulkes et al., who assessed changes in VO2peak at 4- and 12-months post anthracyclines compared with pretreatment levels. At 12-months, the usual-care group lost 7% of VO2peak whereas the exercise group showed a 9% increase relative to pretreatment and netted a 3.5-mL·kg−1·min−1 improvement in VO2peak compared with usual care (p < 0.001).6 These findings suggest that exercise not only attenuates the decline in VO2peak with cancer treatment but may also enhance cardiorespiratory fitness beyond pretreatment levels.

Although exercise consistently enhances cardiorespiratory fitness, its effects on cardiac function are less definitive. Several studies have shown no significant difference in resting left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and global longitudinal strain (GLS) following exercise training.7 Notably, exercise training can improve exercise cardiac reserve, defined as the difference between resting and peak cardiac output with exercise, and may be a more sensitive marker of CTRCD than resting cardiac function.8 In a study of pediatric survivors of cancer, exercise cardiac reserve differentiated survivors with and without impaired cardiorespiratory fitness, despite similar resting cardiac function between groups.8 Similarly, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in patients with breast cancer showed that, whereas resting echocardiographic LVEF and GLS remained unchanged between groups at 4 and 12 months, exercise cardiovascular magnetic resonance detected greater improvements in cardiac reserve in the exercise group than in the usual-care group.6 Taken together, these findings suggest a dynamic, rather than static, assessment of cardiac function may more fully delineate the impact of exercise training on prevention of CTRCD.

Exercise has also been shown to alter several biomarkers used for the early detection of CTRCD. The results of a recent RCT demonstrated that exercise attenuated chemotherapy-induced elevations in troponin levels, indicating a potential cardioprotective effect (8-fold vs. 16-fold increase; p = 0.002), although B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels remained unchanged.6 In contrast, Ansund et al. demonstrated that 16 weeks of structured exercise during adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer resulted in significantly lower N-terminal pro-BNP levels at 1-year follow-up compared with usual care, although no corresponding changes were observed in troponin levels.9 These findings suggest that the timing of troponin measurement (immediately post-treatment versus 1 year later) may be critical for detecting acute changes in cardiac stress. Further research is warranted to determine whether exercise confers long-term protection against elevations in BNP, a key biomarker released in response to myocardial stretch or volume overload and central to the diagnosis and severity assessment of both systolic and diastolic heart failure.

Lastly, emerging data suggest that exercise training following cancer treatment may confer a survival benefit, driven by improvements in cancer-related outcomes. In a recent trial led by Courneya et al., individuals who had undergone surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer were randomly assigned to either a 3-year supervised exercise and behavioral support intervention or health-education only.10 Over an 8-year follow-up period, participants in the exercise group had a 37% reduction in mortality compared with the health-education group. The disease-free survival benefit from exercise was primarily attributable to reductions in liver recurrence (3.6% vs. 6.5%) and new primary cancers (5.2% vs. 9.7%). Participants in the intervention group achieved a mean of 10 MET-hours per week of exercise, equivalent to approximately 150 min of brisk walking weekly, which was associated with significant improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness.10 These findings highlight the potential impact of exercise training on both cancer and CVD outcomes in patients with cancer.

Conclusion

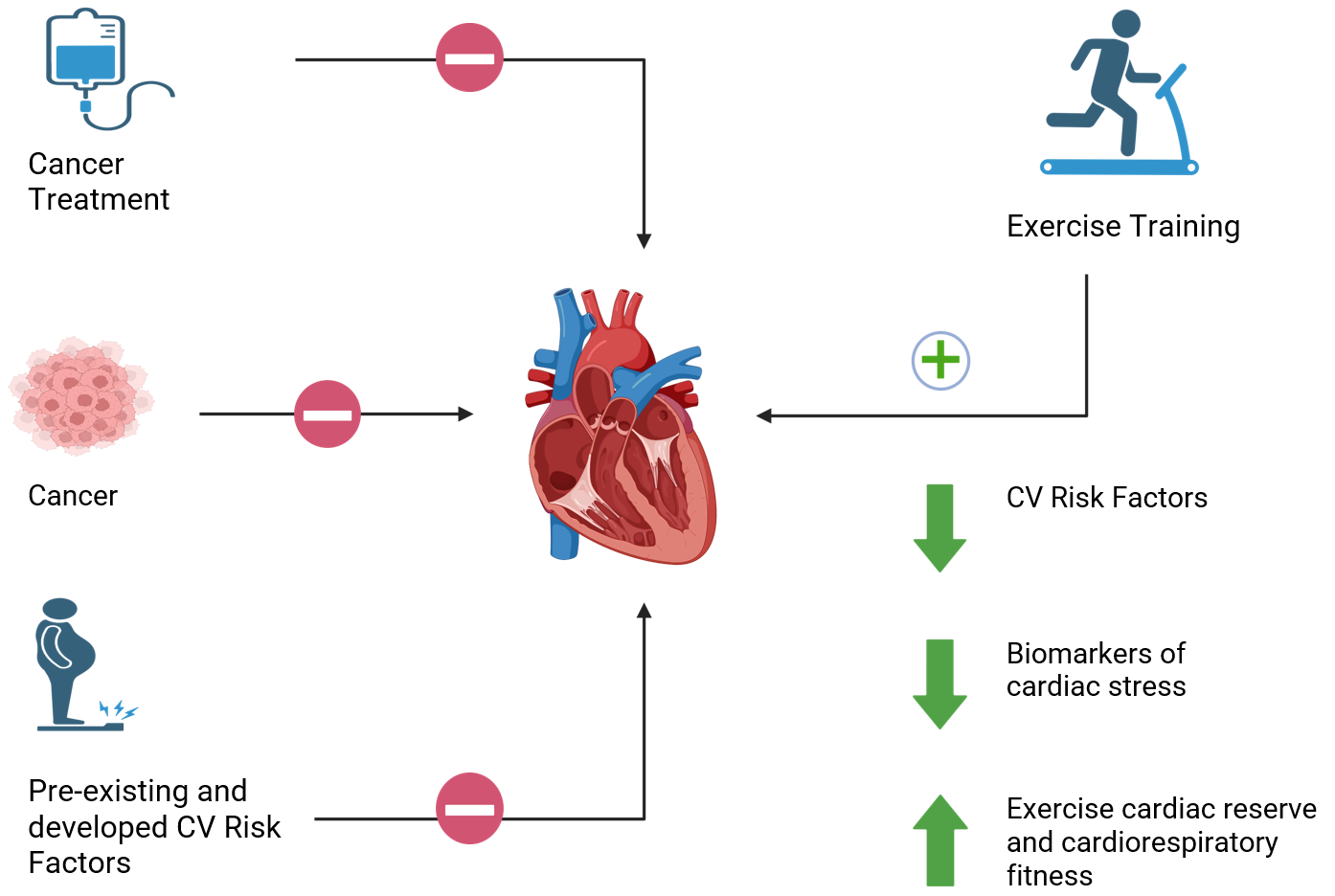

Exercise is a guideline-directed therapy recommended during and after cancer treatment due to its demonstrated effectiveness in improving fatigue, physical functioning, and quality of life. Exercise continues to emerge as a critical intervention in cardio-oncology for mitigating CTRCD and more recently in improving survival in select patients with cancer. The strongest evidence to date is in breast cancer, where exercise has been shown to improve cardiorespiratory fitness, reduce CVD risk factors, and enhance exercise cardiac reserve in patients treated with conventional therapies such as anthracyclines and hormonal agents. Looking ahead, the integration of exercise into oncology care presents new opportunities, particularly with the increasing use of T-cell therapies and targeted treatments. Investigating whether exercise can mitigate the off-target CV effects of these novel therapies is a key area for future research. Additionally, innovative approaches to prescribing and delivering exercise require further exploration. Personalizing exercise interventions may enhance both participation and adherence, with promising opportunities to leverage artificial intelligence in tailoring programs to individual patient needs. Finally, continued emphasis should be placed on integrating exercise into comprehensive cancer care plans, ensuring it is used not only for symptom management but also as a proactive strategy to preserve and protect CV health throughout the cancer continuum (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Role of Exercise in Cardio-Oncology

Created in BioRender. Gilchrist, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/4insg2s.

CV = cardiovascular.

References

- Omland T, Heck SL, Gulati G. The role of cardioprotection in cancer therapy cardiotoxicity: JACC: CardioOncology state-of-the-art review. JACC CardioOncol. 2022;4(1):19-37. Published 2022 Mar 15. doi:10.1016/j.jaccao.2022.01.101

- Adams SC, Rivera-Theurel F, Scott JM, et al. Cardio-oncology rehabilitation and exercise: evidence, priorities, and research standards from the ICOS-CORE working group. Eur Heart J. 2025;46(29):2847-2865. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf100

- Ligibel JA, Bohlke K, May AM, et al. Exercise, diet, and weight management during cancer treatment: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(22):2491-2507. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.00687

- Bigaran A, Zopf E, Gardner J, et al. The effect of exercise training on cardiometabolic health in men with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021;24(1):35-48. doi:10.1038/s41391-020-00273-5

- Ma ZY, Yao SS, Shi YY, Lu NN, Cheng F. Effect of aerobic exercise on cardiotoxic outcomes in women with breast cancer undergoing anthracycline or trastuzumab treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(12):10323-10334. doi:10.1007/s00520-022-07368-w

- Foulkes SJ, Howden EJ, Haykowsky MJ, et al. Exercise for the prevention of anthracycline-induced functional disability and cardiac dysfunction: the BREXIT study. Circulation. 2023;147(7):532-545. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.062814

- Wilson RL, Christopher CN, Yang EH, et al. Incorporating exercise training into cardio-oncology care: current evidence and opportunities: JACC: CardioOncology state-of-the-art review. JACC CardioOncol. 2023;5(5):553-569. Published 2023 Oct 17. doi:10.1016/j.jaccao.2023.08.008

- Foulkes S, Costello BT, Howden EJ, et al. Exercise cardiovascular magnetic resonance reveals reduced cardiac reserve in pediatric cancer survivors with impaired cardiopulmonary fitness. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2020;22(1):64. Published 2020 Sep 7. doi:10.1186/s12968-020-00658-4

- Ansund J, Mijwel S, Bolam KA, et al. High intensity exercise during breast cancer chemotherapy - effects on long-term myocardial damage and physical capacity - data from the OptiTrain RCT. Cardiooncology. 2021;7(1):7. Published 2021 Feb 15. doi:10.1186/s40959-021-00091-1

- Courneya KS, Vardy JL, O'Callaghan CJ, et al. Structured exercise after adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2025;393(1):13-25. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2502760

Clinical Topics: Cardio-Oncology, Cardiovascular Care Team, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Prevention, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, Exercise

Keywords: Cardiorespiratory Fitness, Cancer, Cardiotoxicity, Exercise