The Foundations of Formal Peer Mentorship: A Pilot Grassroots Effort in Fellowship

In July 2015, the pediatric cardiology fellowship program at Columbia University Medical Center and New York Presbyterian Hospital introduced a novel fellow-based peer mentorship program. A previous baseline survey of trainees indicated less than 50 percent satisfaction level with peer mentorship during the initial year of fellowship. A formal program was then designed, implemented and led by the senior (third-year) fellows, who founded peer mentorship "houses," consisting of one fellow from each training year. The senior fellows then developed and standardized year-long programmatic peer mentorship "house" goals and objectives with the primary program elements including in-person initial call supervision, regular "check-ins" or house meetings, and weekly support for academic conference preparation. Educational concepts were presented mid-year at the 2016 ACC Training Section in Chicago, IL. By the end of the academic year, fellow-reported satisfaction increased to 100 percent, with all fellows being "very satisfied" with peer mentorship. This pilot report, along with a more global program perspective, was shared with the ACC Fellows in Training and ACC Early Career Sections.

By establishing a fellow-driven peer mentorship system, our graduate medical training program sought to identify the benefits of a new style of formal peer mentorship. Prior educational literature reflected a more traditional faculty and trainee pairing, and reported that perceived mentorship in medical training could assist with career choices, improve self-confidence in research and positively impact fellowship satisfaction. A new system was created to expand beyond the traditional framework of the faculty and trainee dyad. Senior fellows were utilized as an educational resource to increase peer level support, thereby improving community spirit, leadership skills and first-year fellowship satisfaction.

Now in 2018, the mentorship "house" system has proven to be a sustainable program at our institution. Over the past three years, it has established a training culture of everyday support, fostering substantive and reciprocal relationships among peers. The "houses" are now designed by the chief fellows to actively promote group diversity and inclusion, integrating the many different personal backgrounds and clinical interests of our trainees. The senior fellows have continued to develop and define their peer leadership roles, helping to shape and reinforce core values of the pediatric cardiology fellowship program. Junior fellows consistently receive structured feedback prior to and after academic conference presentations, support for initial in-house calls and guidance navigating the many acute inpatient clinical rotations. "Houses" continue to have regular meetings that extend past introductory fellowship topics and reach towards research collaboration. Mutual in-training collaboration has increased early career guidance, including revision of curriculum vitae and cover letters, as well as feedback from recent graduates regarding advanced training and job opportunities.

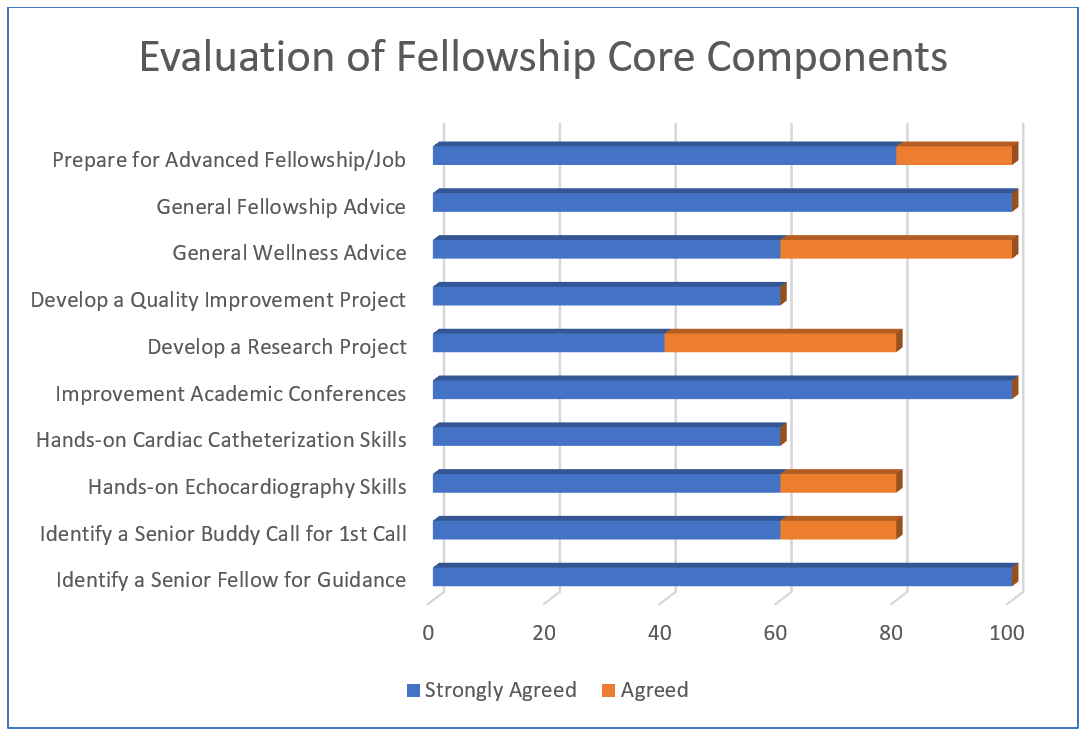

As we start our fourth year, one full cycle of the mentorship has been completed: the inaugural class of first-year fellow mentees progressed to senior fellow mentors and are now the first alumni of the program. Given their unique insights regarding the life-cycle of our peer mentorship program, a focused quality improvement survey was voluntarily completed by these graduates (n=5), with Likert-type scale response options (e.g.: 1- Strongly disagree; 2- Disagree; 3- Neutral, 4- Agree; 5- Strongly agree). In describing the overall peer mentorship experience, 100 percent of the graduated class "strongly agreed" that the formal "house" system was a valuable curriculum addition to post-graduate medical training, and that experiences as a junior peer mentee positively impacted his or her ability to serve as a senior peer mentor. Additionally, 100 percent of fellows either "agreed" or "strongly agreed" the program was a valuable resource for creating and sustaining collaboration during training, and the time commitment at the senior level did not outweigh the cumulative benefits of providing and receiving mentorship throughout all years. In evaluation of the fellowship training program's core components, the "house" system received the best feedback (100 percent "strongly agreed") as a vehicle to improve patient management or scholarly conference presentations, identify a senior fellow for guidance, and provide general cardiology advice (Figure 1A). A consistent majority of fellows also responded positively ("agreed" or more) that the "house" system assisted with development of a research project (80 percent) hands-on instruction for echocardiography (80 percent), providing general wellness advice (100 percent), or future career guidance (100 percent). Quality improvement work and cardiac catheterization skills were ranked the lowest (60 percent).

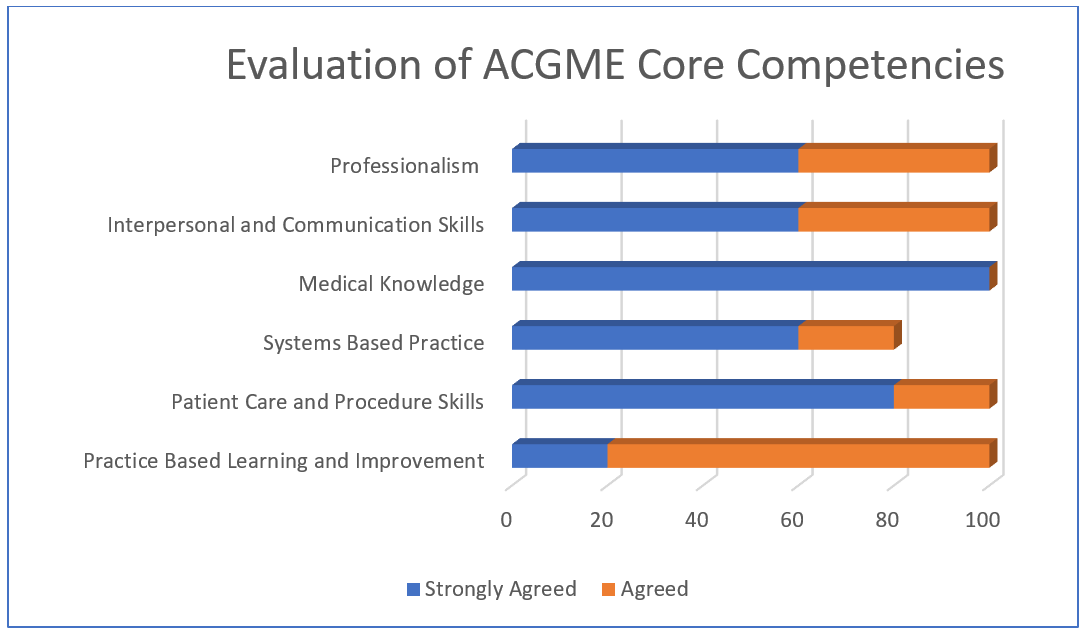

All fellows responded that the "house" system positively impacted their development of at least one or more Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies (Figure 1B). Development of medical knowledge received universally positive feedback (100 percent "strongly agreed"), followed by patient care and procedural skills (80 percent). All fellows provided positive feedback ("agreed" or more) regarding core competency development, with the exception of systems-based practice (80 percent). In summary, all first- and third-year fellows reported that they were "very satisfied" with their formal peer mentorship experience. Although senior fellow peer mentorship satisfaction was not assessed in our initial project, this finding remains consistent with our previous report regarding a high level of first-year fellow peer mentorship satisfaction after system implementation.

While our previous program satisfaction had been reported via Likert-type scales, there is evidence in graduate medical education that milestone assessment, when correctly operationalized, may provide better guidance regarding our understanding of trainee performance, progression and competence. Utilizing a continuum of learner identification scale provided by the American Board of Pediatrics Milestone Project, all of our recently graduated fellows reported interval milestone improvements regarding their ability to independently provide peer mentorship over the training period. To better understand the effect of a formal peer mentorship system within graduate medical training, future work may focus on developing the construct of peer mentorship as an ACGME sub-competency, including more appropriate and specific assessment methods according to educational milestones.

Following publication of the peer mentorship "house" system at Columbia, a similar mentorship strategy was adopted by the UCLA adult cardiology fellowship program. Their group sought to improve both faculty and peer mentorship, and therefore standardized the leadership of a faculty mentor within each house. After a baseline survey, the "house" system was then successfully implemented, and follow up internal data after one year demonstrated markedly improved fellow satisfaction. Inter-institutional collaboration has resulted in ongoing scholarly work, addressing system translation across disciplines and to a larger clinical setting, and culminating with recent abstract acceptance to the 2019 ACC Scientific Session, Foundations in Cardiology Training section.

Many medical training programs still lack a uniform and organized mentorship system, despite evolving literature on its importance. The ACC, in particular, has helped identify this gap of knowledge and practice, publishing several early career articles on the importance of mentoring and mentorship, in addition to a formal presidential address. Ongoing medical education work should continue to systematically focus on both psychosocial and career outcomes with respect to peer mentorship: harnessing positive individual relationships can only help improve our collective professional development. As the ACC has endorsed the value of peer mentorship, we sincerely hope that our current and future medical trainees can utilize these early stages of more formal peer mentorship to construct a more comprehensive strategy of kindness, education and mutual support.

Figure 1A

Figure 1B

This article was authored by Jonathan N. Flyer, MD, FACC; Anna J. Joong, MD; Caitlin S. Haxel, MD; Arash Salavitabar, MD; and Julie S. Glickstein, MD, FACC.