Key Issues in Cardiology Valuation: Anti-Kickback and Stark Law

In our prior article, we provided a basic overview of Fair Market Value (FMV) assessments and how these have become a key aspect in compensation contracts for cardiologists. We also reviewed how practices should focus on demonstrating their value to hospitals and health systems by showcasing leadership efforts within the practice and hospital, attention to strategy, financial performance, quality metrics and access rather than just a focus on relative value units (RVUs). Now, we will share some information on how compensation contracts that seek to recognize value are being influenced by FMV.

Hospital systems typically compensate physicians "around the median" and require productivity to support such compensation. Appointing medical directorships and administrative duties can provide a rationale for a higher level of compensation. Generally, FMV surveys in which compensation, charges, collections and work RVUs (wRVUs) are the only variables, govern compensation in the majority of current models.

Hospitals are reimbursed by Medicare for inpatient services using the Inpatient Prospective Payment system. A patient admitted to the hospital is assigned a Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) at discharge and a global payment is based on this assignment that covers the costs of all services related to an episode of care except the physician's fee. DRG payments are adjusted for case mix complexity based on the severity of the illness, prognosis and treatment difficulty, as well as the need for intervention and resource intensity. In theory, DRG-based reimbursement allows for the comparison of outcomes among hospitals with some adjustment for the severity of illness and resource utilization. It also standardizes payment across a diagnosis and incentivizes efficiency since the payment will be the same for a well-managed or poorly-managed case. Health care systems are incentivized to treat patients as efficiently as possible.

Under Medicare, outpatient services provided by hospitals or physicians in private practice are reimbursed in a fee -for-service model set forth in the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and Physician Fee Schedule (PFS). Technical fees are those charges that relate to the provision of supplies, equipment, facilities and non-physician personnel; these are paid under the OPPS or PFS, depending on setting. The professional fee refers to the payment for the clinician's work and is paid under the PFS. Privately employed physicians offering office based imaging and procedures are able to collect technical fees. Under both the Stark Law and Anti-Kickback Statue, physicians cannot receive payment from a health care organization for either the value or volume of referrals made to the hospital for technical services. In practice, this regulation has been interpreted to mean both private practice and employed physicians may be paid for the professional component of the outpatient studies they perform in the hospital, but cannot share in the technical fees. In 2005, the Deficit Reduction Act limited the technical fee for certain office-based procedures to that of the same service provided by a hospital in an outpatient setting. Thus, studies performed in a hospital outpatient department (HOPD) are reimbursed higher than those performed in a physician office. This, combined with bundling of reimbursement in cardiovascular imaging, has driven outpatient studies to the hospital-based centers and physicians toward employment agreements.

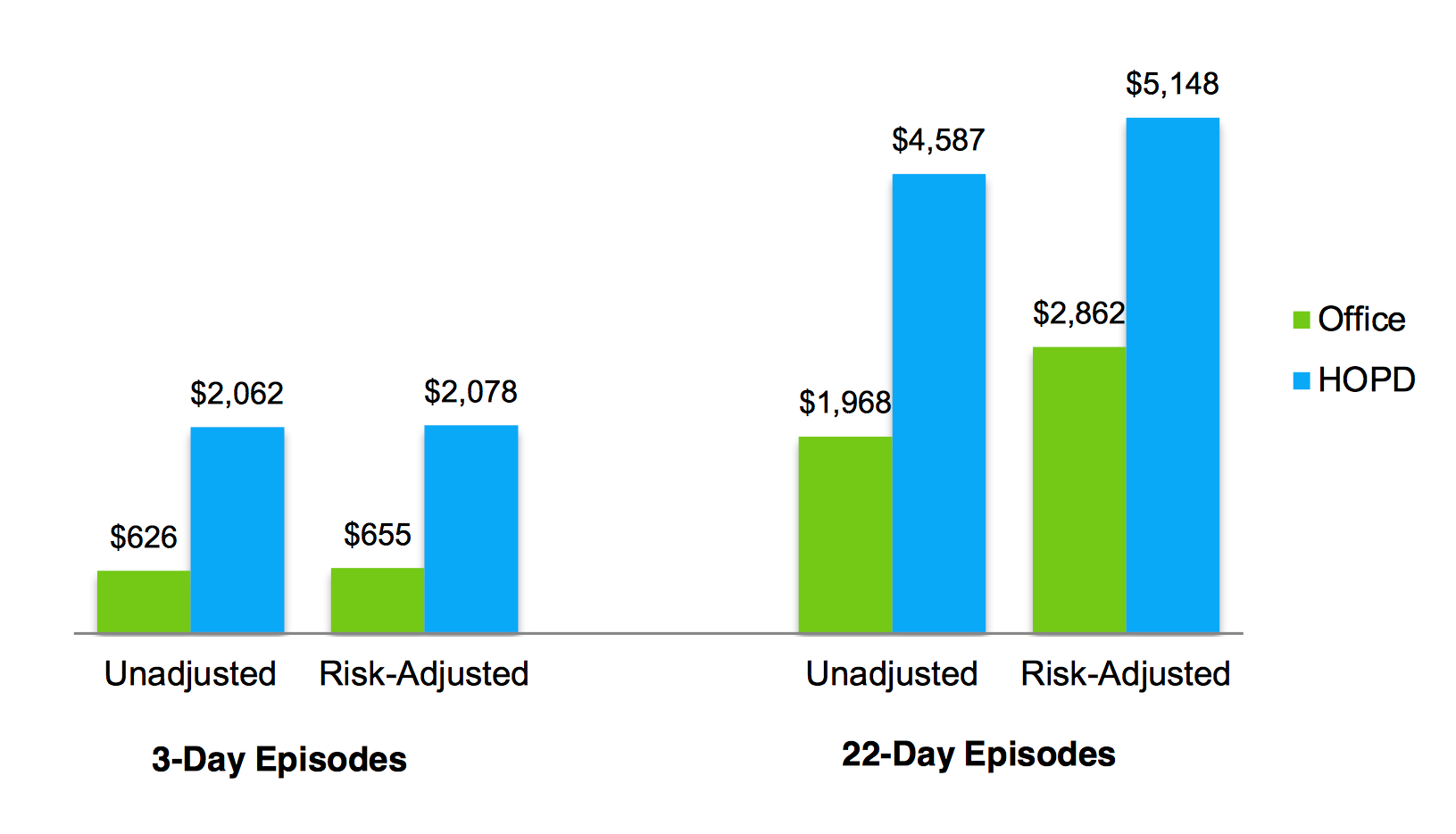

If we look at this example using cardiovascular imaging, we can see that HOPD tests are costlier than those same studies that start in the physician office – regardless of whether we look at three-day or 22-day episodes of care.

Figure 1: Average Payment For Cardiac Imaging Episodes

The application of "commercial reasonableness" is subject to interpretation and each scenario needs to be evaluated on its own merits to determine that the arrangement is compliant with federal and state laws.

Clearly, this approach to compensation brings up many problems in today's market where physicians and health care systems are working together to improve the quality and efficiency of care. As we transition from "volume to value," contracts based solely on wRVUs may become a historical relic. Unfortunately, there are no standard mechanisms yet to assign FMV to contracts heavily weighted toward improved outcomes or efficiency, and no agreement as to how to value educational activities and research. Instead, hospitals and providers are more likely to negotiate with consideration for regulatory agencies and whistle blowers.

As revenue becomes tied to quality, efficiency and effectively managing public health, it is expected that the reimbursement received under the fee-for-service model will become a smaller portion of an organization's bottom line. Programs such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Quality Payment Program, created under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, are emphasizing the need to engage in quality and outcome improvement as a factor of payment. In this rapidly evolving world, employers must not only motivate providers to focus on value but also capture and value these activities appropriately.

Clinicians can (and perhaps should) be rewarded for actions that help to further either the financial and/or the strategic goals of the organization. Examples include financial reward for the achievement of specific targets at the individual, group or service line level. Programs aimed at improved access, patient satisfaction, the development of new clinical services or achieving public health initiatives could be tied to compensation.

Hence, it is best to be involved early in the process. It is in the interest of both the organization and physician that complete an accurate capture of all activities that contribute to the financial and strategic goals of the organization. Input into the organization's strategic goals will provide physicians with an understanding of the new priorities. Being present in meetings with the FMV assessors to ensure that they have received a full and complete picture of how a cardiologist's activities further the needs of the organization is essential. Supporting data is especially helpful, and the earlier in the process it is provided, generally the better. Physicians will want to ensure that they can weave a complete and cogent story of how they help further an organization's financial and strategic goals.

It can be argued that the Stark and Anti-Kickback legislations heavily influence the methodology by which physicians are paid. Therefore, it is important to understand the different compensation distribution models that are being used to directly reward and incentivize physicians.

The following are some compensation distribution facts to make note of. First, while there are many cardiologists whose compensation is 100 percent based on wRVUs, the data shows that this is a methodology only used 55 percent of the time. The other typical compensation distribution methodologies are a blend of wRVU and salary (29 percent), salary plus bonus (10 percent) and an equal share distribution (5 percent).

The data further shows that employed cardiologists are significantly more likely to be paid in a 100 percent wRVU-based manner than independent cardiologists. Why so? Since only hospitals and health systems are subject to the Stark requirements of meeting FMV compensation standards, and most external firms who perform the independent assessment of FMV compensation rely heavily on wRVUs – either for assessing compensation appropriateness for individual physicians or the group as a whole in assessing and offering an opinion of FMV – it should not be surprising that employed cardiologists are much more likely to be compensated solely on wRVUs.

However, the FMV requirement – although heavily linked to wRVU assessment – does not require a 100 percent wRVU compensation distribution methodology. If you are employed, like many cardiologists in the U.S., it is to your advantage to work under a compensation model whereby your employed group earns a "compensation pool" of which you then have control as to how it is distributed amongst your physicians.

The Future

This area is complex, problematic and continuously evolving. Devising a health care system based on quality and efficiency metrics such as those currently required by CMS, yet insisting that we continue to pay physicians based on personal productivity, is not consistent with the Quadruple Aim of the ACC: improved health, better outcomes and lower costs for the patient while promoting professional well-being for the physician. In a health care community that is facing increasing amounts of physician burnout, we must entertain innovative strategies that focus not only on improving the lives of patients in a cost-effective manner but also on reducing the administrative burden on the physician and increasing job satisfaction.

The College must continue to advocate for our patients and our physicians:

- The ACC must continue to strongly advocate to CMS and Congress to thoroughly reexamine these laws to define what is relevant in today's rapidly evolving health care system, and to simplify the enormous regulatory burden that is currently imposed on individual physicians and health care organizations. This may help to advance the newest aim of our organization, the Quadruple Aim. Members of Congress have introduced a bill to exempt alternative payment models from Stark provisions and CMS has indicated that they plan to propose modifications to the law, including clarifications to the definition of "fair market value."

- The ACC must continue to advocate for value-over-volume based reimbursement.

- The ACC must continue to develop, refine and implement appropriate use criteria for cardiovascular procedures.

- The ACC must advocate for a reevaluation of the Stark law in this new environment in which the majority of physicians are employed by hospitals.

Legal Disclaimer

This document is provided for informational purposes only and does not provide legal advice; please consult with your own counsel for legal guidance on compliance with applicable laws and regulations. This document is not intended to and does not encourage any coordination between competitors with respect to compensation practices. To comply with the antitrust laws, competitors should not discuss or agree on the salaries or other compensation.

This article was authored by Alison L. Bailey, MD, FACC; Jesse E. Adams III, MD, FACC; Charles L. Campbell, MD, FACC; and Larry Sobal, MBA, MHA, FACMPE, on behalf of the Publications Workgroup of the CV Management Section.